Sheetlines the Journal of the CHARLES CLOSE SOCIETY for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walking in the Isles of Scilly

WALKING IN THE ISLES OF SCILLY 11 WALKS AND 4 BOAT TRIPS EXPLORING THE BEST OF THE ISLANDS by Paddy Dillon JUNIPER HOUSE, MURLEY MOSS, OXENHOLME ROAD, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA9 7RL www.cicerone.co.uk © Paddy Dillon 2021 CONTENTS Fifth edition 2021 ISBN 978 1 78631 104 7 INTRODUCTION ..................................................5 Location ..........................................................6 Fourth edition 2015 Geology ..........................................................6 Third edition 2009 Ancient history .....................................................7 Second edition 2006 Later history .......................................................9 First edition 2000 Recent history .....................................................10 Getting to the Isles of Scilly ..........................................11 Getting around the Isles of Scilly ......................................13 Printed in China on responsibly sourced paper on behalf of Latitude Press. Boat trips ........................................................15 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Tourist information and accommodation ................................15 All photographs are by the author unless otherwise stated. Maps of the Isles of Scilly ............................................17 The walks ........................................................18 Guided walks .....................................................19 Island flowers .....................................................20 © Crown copyright -

Cornish Archaeology 41–42 Hendhyscans Kernow 2002–3

© 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society CORNISH ARCHAEOLOGY 41–42 HENDHYSCANS KERNOW 2002–3 EDITORS GRAEME KIRKHAM AND PETER HERRING (Published 2006) CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © COPYRIGHT CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2006 No part of this volume may be reproduced without permission of the Society and the relevant author ISSN 0070 024X Typesetting, printing and binding by Arrowsmith, Bristol © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Contents Preface i HENRIETTA QUINNELL Reflections iii CHARLES THOMAS An Iron Age sword and mirror cist burial from Bryher, Isles of Scilly 1 CHARLES JOHNS Excavation of an Early Christian cemetery at Althea Library, Padstow 80 PRU MANNING and PETER STEAD Journeys to the Rock: archaeological investigations at Tregarrick Farm, Roche 107 DICK COLE and ANDY M JONES Chariots of fire: symbols and motifs on recent Iron Age metalwork finds in Cornwall 144 ANNA TYACKE Cornwall Archaeological Society – Devon Archaeological Society joint symposium 2003: 149 archaeology and the media PETER GATHERCOLE, JANE STANLEY and NICHOLAS THOMAS A medieval cross from Lidwell, Stoke Climsland 161 SAM TURNER Recent work by the Historic Environment Service, Cornwall County Council 165 Recent work in Cornwall by Exeter Archaeology 194 Obituary: R D Penhallurick 198 CHARLES THOMAS © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Preface This double-volume of Cornish Archaeology marks the start of its fifth decade of publication. Your Editors and General Committee considered this milestone an appropriate point to review its presentation and initiate some changes to the style which has served us so well for the last four decades. The genesis of this style, with its hallmark yellow card cover, is described on a following page by our founding Editor, Professor Charles Thomas. -

Isles of Scilly

Isles of Scilly Naturetrek Tour Report 5 - 12 May 2007 Report compiled by Paul Dukes Photographs by Sarah Barnes Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Isles of Scilly Tour Leader: Paul Dukes Participants: Sarah Barnes Alistair and Joan Ainsworth Diana Chadwick Geoff and Lynn Vorley Geoff and Barbara Perkins Pete Belcher and Pam Jackson Benjamin & Olivia Richardson Day 1 Saturday 5th May After travelling to Penzance from various parts of the country most of the Naturetrek group made their way to the Lighthouse pier bright and early to board the Scillonian 111 ferry. It was a misty spring morning with poor visibility which represented no problem for the steamship but threatened to delay the journey of the tour members who had opted to travel to Scilly by air. With the World Gig Racing Championships taking place on the islands over the weekend I was expecting a full complement of passengers on the vessel but whilst it was undoubtedly busy the numbers were fewer than I feared. Eventually the ropes were cast off and we began the three hour sailing to St Mary’s, passing several summer plumaged Great Northern Divers before we had ventured far into Mount’s Bay. Others were observed on the flat calm sea as we drew opposite Newlyn and in total at least six birds were noted, most in summer or partial summer dress. We were scanning for Basking Sharks but sadly none were seen although just a month later over 40 were counted between Penzance and Land’s End! As we made our way parallel with the South Cornish coast the cliffs were barely visible in the mist becoming more and more indistinct as our route took us further out to sea. -

JNCC Coastal Directories Project Team

Coasts and seas of the United Kingdom Region 11 The Western Approaches: Falmouth Bay to Kenfig edited by J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson, S.S. Kaznowska, J.P. Doody, N.C. Davidson & A.L. Buck Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House, City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY UK ©JNCC 1996 This volume has been produced by the Coastal Directories Project of the JNCC on behalf of the project Steering Group and supported by WWF-UK. JNCC Coastal Directories Project Team Project directors Dr J.P. Doody, Dr N.C. Davidson Project management and co-ordination J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson Editing and publication S.S. Kaznowska, J.C. Brooksbank, A.L. Buck Administration & editorial assistance C.A. Smith, R. Keddie, J. Plaza, S. Palasiuk, N.M. Stevenson The project receives guidance from a Steering Group which has more than 200 members. More detailed information and advice came from the members of the Core Steering Group, which is composed as follows: Dr J.M. Baxter Scottish Natural Heritage R.J. Bleakley Department of the Environment, Northern Ireland R. Bradley The Association of Sea Fisheries Committees of England and Wales Dr J.P. Doody Joint Nature Conservation Committee B. Empson Environment Agency Dr K. Hiscock Joint Nature Conservation Committee C. Gilbert Kent County Council & National Coasts and Estuaries Advisory Group Prof. S.J. Lockwood MAFF Directorate of Fisheries Research C.R. Macduff-Duncan Esso UK (on behalf of the UK Offshore Operators Association) Dr D.J. Murison Scottish Office Agriculture, Environment & Fisheries Department Dr H.J. Prosser Welsh Office Dr J.S. -

ADMIRALTY NOTICES to MARINERS Weekly Edition 22 31 May 2018 (Published on the ADMIRALTY Website 21 May 2018)

Notices 2346--2469/18 T & P Notices in Force ADMIRALTY NOTICES TO MARINERS Weekly Edition 22 31 May 2018 (Published on the ADMIRALTY website 21 May 2018) CONTENTS I Explanatory Notes. Publications List II ADMIRALTY Notices to Mariners. Updates to Standard Nautical Charts III Reprints of NAVAREA I Navigational Warnings IV Updates to ADMIRALTY Sailing Directions V Updates to ADMIRALTY List of Lights and Fog Signals VI Updates to ADMIRALTY List of Radio Signals VII Updates to Miscellaneous ADMIRALTY Nautical Publications VIII Updates to ADMIRALTY Digital Services For information on how to update your ADMIRALTY products using ADMIRALTY Notices to Mariners, please refer to NP294 How to Keep Your ADMIRALTY Products Up--to--Date. Mariners are requested to inform the UKHO immediately of the discovery of new or suspected dangers to navigation, observed changes to navigational aids and of shortcomings in both paper and digital ADMIRALTY Charts or Publications. The H--Note App helps you to send H--Notes to the UKHO, using your device’s camera, GPS and email. It is available for free download on Google Play and on the App Store. The Hydrographic Note Form (H102) should be used to forward this information and to report any ENC display issues. H102A should be used for reporting changes to Port Information. H102B should be used for reporting GPS/Chart Datum observations. Copies of these forms can be found at the back of this bulletin and on the UKHO website. The following communication facilities are available: NMs on ADMIRALTY website: Web: admiralty.co.uk/msi Searchable Notices to Mariners: Web: www.ukho.gov.uk/nmwebsearch Urgent navigational information: e--mail: [email protected] Phone: +44(0)1823 353448 Fax: +44(0)1823 322352 H102 forms e--mail: [email protected] (see back pages of this Weekly Edition) Post: UKHO, Admiralty Way, Taunton, Somerset, TA1 2DN, UK All other enquiries/information e--mail: [email protected] Phone: +44(0)1823 484444 (24/7) Crown Copyright 2018. -

Breeding Seabirds on the Isles of Scilly Vickie Heaney, Leigh Lock, Paul St Pierre and Andy Brown

BB August 2008 22/7/08 12:26 Page 418 Important Bird Areas: Breeding seabirds on the Isles of Scilly Vickie Heaney, Leigh Lock, Paul St Pierre and Andy Brown Razorbills Alca torda Ren Hathway ABSTRACT The Isles of Scilly are long famous for attracting rare migrant birds, and much-visited in spring and autumn by those in search of them, but it is much less widely appreciated that the islands also support an outstanding and internationally important assemblage of breeding seabirds.We document the present status and distribution of seabirds on the islands, set populations in their regional, national and international contexts, and review recent and historical changes in numbers. In the light of some alarming population trends, we discuss the possible roles of persecution, disturbance, predation, habitat change, waste and fisheries management, climate change and pollution in bringing about these changes. Finally, we identify a range of actions that we believe will do much to improve the fortunes of the seabirds breeding in the archipelago. 418 © British Birds 101 • August 2008 • 418–438 BB August 2008 22/7/08 12:26 Page 419 Breeding seabirds on the Isles of Scilly he Isles of Scilly are situated some 45 km seabird interest, it is not surprising that many of to the west of the southwest tip of the the older county avifaunas refer to the presence TBritish mainland. Five inhabited islands of seabirds in some numbers. However, few of and at least 300 smaller, uninhabited islands, the references are quantitative and information islets and rocks cover a total area of 16 km2. -

SOUTH WEST ENGLAND Frequently Asked Questions

SOUTH WEST ENGLAND Frequently Asked Questions Product Information & Key Contacts 2016 Frequently Asked Questions Bath Bath Visitor Information Centre Abbey Chambers Abbey Churchyard Bath BA1 1LY Key contact: Katie Sandercock Telephone: 01225 322 448 Email: [email protected] Website: www.visitbath.co.uk Lead product Nourished by natural hot springs, Bath is a UNESCO World Heritage city with stunning architecture, great shopping and iconic attractions. Rich in Roman and Georgian heritage, the city has been attracting visitors with its obvious charms for well over 2000 years and is now the leading Spa destination of the UK. Some of the highlights of the city include: The Roman Baths - constructed around 70 AD as a grand bathing and socialising complex. It is now one of the best preserved Roman remains in the world. Thermae Bath Spa – bathe in Bath’s natural thermal waters. Highlights include the indoor Minerva Bath, steam rooms, and an open-air rooftop pool with amazing views over the city. A fantastic range of treatments including massage, facials and water treatments can be booked in advance. Gainsborough Bath Spa Hotel – Britain’s first natural thermal spa hotel. Opened in July 2015. A five-star luxury hotel located in the centre of Bath. Facilities include 99 bedrooms (some with access to Bath’s spring water in their own bathrooms), The Spa Village Bath and Johan Lafer’s ‘Dining Without Borders’ restaurant. Bath Abbey - Magnificent stained glass windows, columns of honey-gold stone and some of the finest fan vaulting in the world, create an extraordinary experience of light and space. -

CARBINIDAE of CORNWALL Keith NA Alexander

CARBINIDAE OF CORNWALL Keith NA Alexander PB 1 Family CARABIDAE Ground Beetles The RDB species are: The county list presently stands at 238 species which appear to have been reliably recorded, but this includes • Grasslands on free-draining soils, presumably maintained either by exposure or grazing: 6 which appear to be extinct in the county, at least three casual vagrants/immigrants, two introductions, Harpalus honestus – see extinct species above two synathropic (and presumed long-term introductions) and one recent colonist. That makes 229 resident • Open stony, sparsely-vegetated areas on free-draining soils presumably maintained either by exposure breeding species, of which about 63% (147) are RDB (8), Nationally Scarce (46) or rare in the county (93). or grazing: Ophonus puncticollis – see extinct species above Where a species has been accorded “Nationally Scarce” or “British Red Data Book” status this is shown • On dry sandy soils, usually on coast, presumably maintained by exposure or grazing: immediately following the scientific name. Ophonus sabulicola (Looe, VCH) The various categories are essentially as follows: • Open heath vegetation, generally maintained by grazing: Poecilus kugelanni – see BAP species above RDB - species which are only known in Britain from fewer than 16 of the 10km squares of the National Grid. • Unimproved flushed grass pastures with Devil’s-bit-scabious: • Category 1 Endangered - taxa in danger of extinction Lebia cruxminor (‘Bodmin Moor’, 1972 & Treneglos, 1844) • Category 2 Vulnerable - taxa believed -

RCC Pilotage Foundation Isles of Scilly 5Th Edition 2010 ISBN 978 085288 850 6

RCC Pilotage Foundation Isles of Scilly 5th Edition 2010 ISBN 978 085288 850 6 Supplement No.3 September 2017 Hulman beacon Caution S entrance to New Grimsby Sound. Green g radar reflector Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of on pole Fl.G.4s. this supplement. However, it contains selected information and thus is not definitive and does not include all known information on the subject in hand. The authors, the RCC Pilotage Foundation and Imray Laurie Norie & Wilson Ltd believe this supplement to be a useful aid to prudent navigation, but the safety of a vessel depends ultimately on the judgement of the navigator, who should assess all information, published or unpublished, available to him/her. With the increasing precision of modern position-fixing methods, allowance must be made for inaccuracies in latitude and longitude on many charts, inevitably perpetuated on some harbour plans. Modern surveys specify which datum is used together with correction figures if required, but older editions should be used with caution, particularly in restricted visibility. This supplement is cumulative and the latest information is marked in blue . Warning The Tresco harbourmaster has warned (March 2015) that Woolpack starboard entry beacon 2017 the storms over winter 2014/15 have significantly altered the sandy seabed in the shallows between Samson, Bryher, Tresco, Tean and St Martin’s and great caution should be Page 12 Magnetic variation exercised in the southern approaches to these islands; place 2°35W (2017) decreasing by 09’ each year. little reliance on charted depths in these areas. It is thought that there has been little significant change to the main Page 15 Passage from the East approaches to Old and New Grimsby Sounds from the N. -

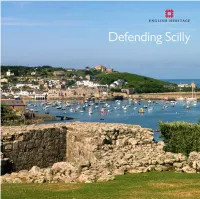

Defending Scilly

Defending Scilly 46992_Text.indd 1 21/1/11 11:56:39 46992_Text.indd 2 21/1/11 11:56:56 Defending Scilly Mark Bowden and Allan Brodie 46992_Text.indd 3 21/1/11 11:57:03 Front cover Published by English Heritage, Kemble Drive, Swindon SN2 2GZ The incomplete Harry’s Walls of the www.english-heritage.org.uk early 1550s overlook the harbour and English Heritage is the Government’s statutory adviser on all aspects of the historic environment. St Mary’s Pool. In the distance on the © English Heritage 2011 hilltop is Star Castle with the earliest parts of the Garrison Walls on the Images (except as otherwise shown) © English Heritage.NMR hillside below. [DP085489] Maps on pages 95, 97 and the inside back cover are © Crown Copyright and database right 2011. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019088. Inside front cover First published 2011 Woolpack Battery, the most heavily armed battery of the 1740s, commanded ISBN 978 1 84802 043 6 St Mary’s Sound. Its strategic location led to the installation of a Defence Product code 51530 Electric Light position in front of it in c 1900 and a pillbox was inserted into British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data the tip of the battery during the Second A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. World War. All rights reserved [NMR 26571/007] No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without Frontispiece permission in writing from the publisher. -

Wildlife Travel Scilly Autumn 2011

Isles of Scilly species lists and trip report, 15th-22nd September 2011 WILDLIFE TRAVEL Isles of Scilly 2011 th nd Isles of Scilly species lists and trip report, 15 -22 September 2011 # DATE LOCATIONS 1 15th Sept Scillonian & St Mary’s: The Garrison & Hugh Town 2 16th Sept St Agnes 3 17th Sept The Eastern Isles and St Martin’s 4 18th Sept Tresco 5 19th Sept St Mary’s: Telegraph, Maypole, Holy Vale, Higher Moors, Lower Moors 6 20th Sept Bryher 7 21st Sept St Mary’s: Halangy Down, Telegraph, Juliet’s Garden, Peninnis Head 8 22nd Sept St Mary’s & Scillonian LIST OF TRAVELLERS Leaders Rosemary Parslow Cornwall Philip Precey Cambridge www.wildlife-travel.co.uk 2 th nd Isles of Scilly species lists and trip report, 15 -22 September 2011 15th September 2011. The Garrison & Hugh Town, St Marys A pretty uneventful journey from Penzance on the Scillonian included, for some, perhaps the briefest ever sighting of a single Common Dolphin, which appeared next to the boat for all of 2 seconds before disappearing, never to be seen again. There were plenty of Gannets along the way, as well as a Fulmar or two and a handful of Guillemots. Arriving on the quay at Hugh Town, we met up with Rosemary and made our way to the Lyonnesse guesthouse, our home for the next week. All settled in, and with lunch sorted, we set off for a wander around the Garrison headland. On a sunny afternoon, we started with a passing Clouded Yellow and continued the butterfly theme by finding Speckled Wood, Meadow Brown and a single Small Tortoiseshell, as well as at least 5 Hummingbird Hawk-moths. -

Site Improvement Plan Isles of Scilly Complex

Improvement Programme for England's Natura 2000 Sites (IPENS) Planning for the Future Site Improvement Plan Isles of Scilly Complex Site Improvement Plans (SIPs) have been developed for each Natura 2000 site in England as part of the Improvement Programme for England's Natura 2000 sites (IPENS). Natura 2000 sites is the combined term for sites designated as Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) and Special Protected Areas (SPA). This work has been financially supported by LIFE, a financial instrument of the European Community. The plan provides a high level overview of the issues (both current and predicted) affecting the condition of the Natura 2000 features on the site(s) and outlines the priority measures required to improve the condition of the features. It does not cover issues where remedial actions are already in place or ongoing management activities which are required for maintenance. The SIP consists of three parts: a Summary table, which sets out the priority Issues and Measures; a detailed Actions table, which sets out who needs to do what, when and how much it is estimated to cost; and a set of tables containing contextual information and links. Once this current programme ends, it is anticipated that Natural England and others, working with landowners and managers, will all play a role in delivering the priority measures to improve the condition of the features on these sites. The SIPs are based on Natural England's current evidence and knowledge. The SIPs are not legal documents, they are live documents that will be updated to reflect changes in our evidence/knowledge and as actions get underway.