Downloaded from the Journal Homepage (See Below)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Culinarycooperative BARNDIVA DINNER 707.431.0100

DRY CREEK VALLEY CULINARY COOPERATIVE Connecting the best in local food and wine. MENU BOOK wdcv.com/culinarycooperative BARNDIVA DINNER 707.431.0100 first heirloom beets, endive, watercress, warm chèvre croquettes, baby radish 14 crispy quail, warm potato salad, frisee, smoked ham hock, quail egg 19 cauliflower soup, caramelized florets, raisin, fried caper, toasted almond, sage 12 beef carpaccio, thinly sliced filet mignon, hen of the woods tempura, horseradish 17 crisp butter lettuces, ruby red grapefruit, radish, citrus vinaigrette 11 shaved apple salad, baby lettuces, fennel, fines herbs, pomegranate, champagne vinaigrette 9 sliced raw yellowfin tuna, sticky rice, avocado, soy, pickled fresno chili 18 marin triple cream brie, poached apricot marmalade, warm brioche 16 main herb roasted filet mignon, olive oil smashed potato, spinach, caramelized onion jam, bone marrow “tater tot” 42 pan roasted john dory, mussels, chorizo, artichoke, broccolini, saffron tomato broth 34 crispy young chicken, roasted brussels sprouts, ricotta & egg yolk ravioli, serrano ham vinaigrette 26 sautéed pacific swordfish, fregola sarda, green goddess, cracked crab, olive, tomato confit 32 bacon wrapped pork tenderloin, stone-ground polenta, fennel, apple “relish,” crispy proscuitto 28 sonoma duck, crispy leg, sliced breast, caramelized endive, huckleberry, ricotta pierogi, scallion 36 “the vegetarian” this is a dish handcrafted daily by the chef according to the seasonal market 25 for the table bd frites, crisp kennebec potatoes, spicy ketchup 12 chèvre croquettes, -

Ballroom Iraval Wedding Package

THE MOCKINGBIRD RE M iraval B allroom M 2018-2019 Wedding Package 838 North Bedford Street East Bridgewater, MA 02333 508-378-4911 www.mockingbirdrestaurant.com 10-2017 Miraval B allroom Located in The Mockingbird Restaurant 838 North Bedford Street, East Bridgewater, MA 02333 508-378-4911 www.mockingbirdrestaurant.com 2018 Wedding Special Offers 2018 Wedding Special $15.00 off per person for any remaining 2018 dates Weekday Discount Monday - Thursday excluding Holidays $ 20.00 off per person ( discount only applied to entrée price person) Winter Wedding Discount December - January - February - March $ 15.00 off per person ( discount only applied to entrée price person) Spring Wedding Discount —— April —— $ 5.00 off per person ( discount only applied to entrée price person) Friday or Sunday May - November 2019 dates $5.00 off per person Military Wedding Discount Must be an Active Member of the Military (5% discount only applied to entrée price person) Only one discount per event, minimum of 100 guests for discount to apply cannot be combined, Offer may be discontinued or change at any time 2 All of our Wedding Packages include: Personalized Planning and Coordination with our professional event planner/consultant Personal Maître d’ at reception from start to finish You select what time your wedding starts as we only host one wedding per day Complimentary Tasting for the Bride and Groom Five Hour Reception you choose your start time as we only host one wedding per day. Endless Photo Opportunities Modern Private Bridal Suite with a private -

300-012 PDF Rebranding-Weddingmenu.Indd

Wedding Menu LaKota Oaks Signature Celebration FIVE-HOUR OPEN BAR INCLUDING ONE HOUR COCKTAIL RECEPTION LAKOTA OAKS SIGNATURE COCKTAIL CHOICE OF SIX BUTLER PASSED HORS D’OEUVRES CHOICE OF ONE COLD DISPLAY CHOICE OF TWO INTERACTIVE STATIONS FOUR COURSE PLATED DINNER SPARKLING WINE TOAST BEVERAGE SERVICE THROUGHOUT DINNER CUSTOM WEDDING CAKE BY DIMARE’S COFFEE & TEA SERVICE LaKota Oaks | 32 Weed Avenue, Norwalk, CT | 203-852-7329 | LaKotaOaks.com Wedding Menu Passed Hors d’oeuvres choose six COLD SELECTIONS: WARM SELECTIONS: Crostini Crimini Mushroom house made ricotta, oven roasted tomato, aged balsamic stuffed with roasted red pepper, smoked goat cheese Bruschetta Mini Grilled Cheese roasted pepper, gorgonzola, red wine gastrique brie, bosc pear, brioche Duck Prosciutto Grilled Peaches* jumbo asparagus, pomegranate molasses pancetta wrapped, reduced balsamic Bleu Cheese Mousse Flatbread cucumber, citrus fig, goat cheese, arugula Ceviche Skewered Herb Grilled Chicken bay scallop, jalapeno avocado dressing Tuna Tartar Atlantic Cod Fritter cucumber round, wasabi aioli black garlic aioli Soy Cured Salmon Beef Satay Asian pear, crème fraiche Korean bbq style Mini Reuben pastrami, sauerkraut, Swiss cheese, Russian dressing, rye *seasonal item LaKota Oaks | 32 Weed Avenue, Norwalk, CT | 203-852-7329 | LaKotaOaks.com Wedding Menu Cold Displays choose one LOCAL ARTISAN CHEESES: FROM THE GARDEN: “5 Spoke Creamery” crawford cloth bound cheddar Marinated and grilled zucchini, yellow squash, bell peppers, Herbal Jack English cotswold eggplant, asparagus -

Artisanal Charcutterie

ARTISANAL CHARCUTTERIE LIST OF PRODUCTS & DESCRIPTION Guanciale Guanciale is an Italian cured meat product prepared from pork jowl or cheeks. Its name is derived from guancia, Italian for cheek. 520 THB/KG Its flavor is stronger than other pork products, such as pancetta, and its texture is more delicate. Upon cooking, the fat typically melts away giving great depth of flavor to the dishes and sauces it is used in. In cuisine Guanciale may be cut and eaten directly in small portions, but is often used as a pasta ingredient.It is used in dishes like spaghetti alla carbonara and sauces like sugo all'amatriciana. Coppa / Cabecero de lomo Capocollo or Coppa is a traditional Italian and Corsican pork cold cut (salume) made from the dry-cured muscle running from the neck to the 4th or 5th rib of the pork shoulder or neck. 1030 THB/ Kg It is a whole muscle salume, dry cured and, typically, sliced very thin. It is similar to the more widely known cured ham or prosciutto, because they are both pork-derived cold-cuts that are used in similar dishes This cut is typically called capocollo or coppa in much of Italy and Corsica. Regional terms include capicollo (Campania), capicollu (Corsica), finocchiata (Tuscany), lonza (Lazio) and lonzino (Marche and Abruzzo). Capocollo is esteemed for its delicate flavor and tender, fatty texture and is often more expensive than most other salumi. In many countries, it is often sold as a gourmet food item. It is usually sliced thin for use in antipasto or sandwiches such as muffulettas, Italian grinders and subs, and panini as well as some traditional Italian pizza. -

Produce Size Serves Price* Weight/ Quantity Name

PLEASE CIRCLE YOUR PREFERRED CHOICE OF COLLECTION TIME TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY 22 ND DECEMBER 23RD DECEMBER 24TH DECEMBER 8am – 9am 7am – 8am 9.30am – 11.30am 9am – 10am 8am – 9am 10am – 11am 11.30am – 1.30pm 11am – 12noon 9am – 10am 12noon – 1pm 1.30pm – 3.30pm 1pm – 2pm 10am – 11am NAME 2pm – 3pm 3.30pm - 5.30pm 3pm – 4pm ADDRESS 11am – 12noon 4pm – 6pm POSTCODE DATE OTHER THAN ABOVE: TELEPHONE £10 DEPOSIT ORDER NUMBER EMAIL (NON-REFUNDABLE) (FOR OFFICE USE) If you do not wish to be kept up-to date with Cheerbrook news, activities & promotions please tick here: WEIGHT/ PRODUCE SIZE SERVES PRICE* QUANTITY FESTIVE FEAST WITH CRANBERRY & ORANGE SAUSAGE MEAT 1 - 4.5kg as a single joint. Succulent turkey, wrapped around a dry cured pork tenderloin, stuffed with our Please specify the 4 - 15 £15.75/kg speciality pork, cranberry & orange sausage meat, wrapped in bacon - delicious, weight you require easy to carve & no waste FESTIVE FEAST WITH ROAST ONION & SAGE SAUSAGE MEAT 1 - 4.5kg as a single joint. Succulent turkey, wrapped around a dry cured pork tenderloin, stuffed with our Please specify the 4 - 15 £15.75/kg speciality pork, sage & onion sausage meat, wrapped in bacon - delicious, easy to weight you require carve & no waste Small 4 - 5.5kg 8 - 11 £10.95/kg WHOLE FRESH BARN TURKEY Medium 5.6 - 6.8kg 11 - 13 £10.95/kg Supplied for 18 years by the Garnett family, near Knutsford. Reared with care for a Large 6.9 - 8.6kg 13 - 17 £10.95/kg tender & flavoursome roast (includes giblets) Extra Large 8.7 - 11kg 17 - 22 £10.95/kg Small 4 - 5.5kg 8 - 10 £12.90/kg TURKEY CROWN Turkey breast on the bone. -

Plussea-Food-Menu.Pdf

COLD APPETISERS . ΚΡΥΑ ΟΡΕΚΤΙΚΑ Hummus Χούμοι Traditional chickpea dip served with crispy pitta bread 7 Παραδοσιακό ντιπ από ρεβίθια, σερβίρεται µε τραγανή πίτα 7 Selection of Dips Επιλογή από σαλάτες-αλοιφές Baba ganoush, guacamole and spicy cheese dip, served with grilled pitta bread and tortilla chips 8 Μελιτζανοσαλάτα, γουακαµόλε και τυροκαυτερή, συνοδεύονται από πιτούλες ψηµένες στη σχάρα και τσιπς τορτίγιας 8 Caprese Καπρέζε Burrata mozzarella, tomatoes and herbed croutons, served with basil pesto and a balsamic glaze 12 Βουτυράτη µοτσαρέλα µπουράτα, ντοµάτα και κρουτόν βοτάνων, µε πέστο βασιλικού και γλάσο από βαλσάµικο ξύδι 12 Beef Carpaccio Καρπάτσιο από Μοσχάρι Thin slices of raw beef with flakes of Grana Padano cheese, capers, and baby arugula, drizzled with truffle oil and a balsamic glaze 16.50 Λεπτές φέτες από ωµό µοσχαρίσιο φιλέτο µε νιφάδες τυριού αργής ωρίµανσης Grana Padano, κάπαρη και τρυφερά φύλλα ρόκας, ραντισµένες µε λάδι τρούφας και γλάσο από βαλσάµικο ξύδι 16.50 Prawn Carpaccio Καρπάτσιο Γαρίδας With crab cake, mustard and a lime dressing 18.50 Σερβίρεται µε µπιφτέκι από καβούρι, µουστάρδα και σάλτσα µοσχολέµονου 18.50 Salmon Tartare Ταρταρ Σολωµού Served with avocado parfait and crispy bread 16.50 Σερβίρεται µε παρφέ αβοκάντο και τραγανό ψωµάκι 16.50 Cheese Platter Πλατό Τυριών A selection of local and international cheeses accompanied by marinated olives, raspberry jam, crispy croutons and crackers 19 Επιλογή από εγχώρια και εισαγόµενα τυριά, µε µαριναρισµένες ελιές, µαρµελάδα βατόµουρο, τραγανά κρουτόν και κράκερ 19 Antipasti Misti Πλατό Tυριών και Aλλαντικών Local and imported cheeses and cured meats, accompanied by marinated olives and crispy croutons 22.50 Εγχώρια και εισαγόµενα τυριά και αλλαντικά, µε µαριναρισµένες ελιές και τραγανά κρουτόν 22.50 Prawn and Crab Meat Ψίχα από Γαρίδα και Καβούρι Radish and celeriac salad with a light Dijon mustard dressing 14.50 Με σαλάτα από ραπανάκι και σελινόριζα κι ελαφριά σάλτσα µουστάρδας Dijon 14.50 HOT APPETISERS . -

View Our Menu (PDF)

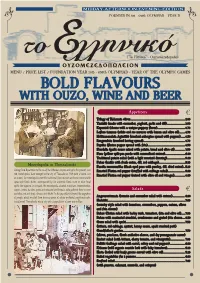

MIDDAY-AFTERNOON-EVENING-EDITION FOUNDED IN 2011 - 698th OLYMPIAD – YEAR D' ("To Elliniko" - Ouzomezedopolio) MENU / PRICE LIST / FOUNDATION YEAR 2015 - 698th OLYMPIAD - YEAR OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES BOLD FLAVOURS WITH OUZO, WINE AND BEER Appetizers € Trilogy of Kalamata olives................................................................................ 2.80 Tzatziki (made with cucumber, yoghurt, garlic and dill)........................... 3.90 Kopanisti (cheese with a unique peppery flavor)......................................... 4.70 Lefkos taramas (white cod roe mousse with lemon and olive oil)......... 4.70 Melitzanosalata Agioritiki (smoked aubergine spread with peppers)....... 4.50 Rengosalata (smoked herring spread)............................................................. 4.70 Paprika (florine pepper spread with feta)....................................................... 4.50 Skordalia (garlic sauce mixed with potato, bread and olive oil)............... 3.90 Fava (yellow split-pea purée with caramelised onions).............................. 6.80 Traditional potato salad (with a light mustard dressing)........................... 5.80 Fakes (lentils with fresh onion, dill, red cabbage)....................................... 5.20 Mezedopolia in Thessaloniki Fasolia mavromatika (black eyed peas with parsley, dill, dried onion)... 5.20 Dating from Byzantium to the era of the Ottoman empire and up to the present, over Roasted Florina red pepper (stuffed with cabbage salad)......................... 5.00 700 ‘mezedopolia’ have emerged in the city of Thessaloniki. Not quite a tavern, nor Roasted Florina red pepper (served with olive oil and vinegar)................ 4.80 an ouzeri, the mezedopolia resemble traditional food markets and serve innumerable tapas-style Greek dishes, accompanied by the authentic Greek ouzo or other local spirits like tsipouro. In the past, the mezedopolia attracted musicians, impressionists, singers, jesters, dandies, poets and educated intellectuals, who gathered there to meet Salads € and relax, eat and drink, discuss and debate. -

Catálogo De Productos Product Catalogue Jamones González S.L

Catálogo De Productos Product catalogue Jamones González S.L. Estación, 20 · Laxosa · Lugo T. (+34) 982 300 900 · F. (+34) 982 300 010 www.jamones-gonzalez.es Índice / contents 1. Jamones / HAMS 7. Salados / salted pork meat 1.1 Jamón curado / Cured Ham....................................................... p.6 7.1 Pies y manos / Front and rear Hooves.....................................p.32 - Gran reserva..................................................................................p.6 7.2 Orejas / Ears........................................................................p.32 - Reserva.........................................................................................p.6 7.3 Costilla tiras / Rack of ribs....................................................p.33 - Bodega.........................................................................................p.7 7.4 Rabos / Tails.......................................................................p.33 1.2 Jamón curado deshuesado / Boneless cured ham....................p.7 7.5 Espinazo / Spine..................................................................p.34 - Reserva con piel / Reserva with skin..........................................p.7 7.6 Dientes / Teeth....................................................................p.34 - Reserva sin piel / Skinned reserva.............................................p.8 7.7 Morro sin hueso / Boned snout............................................p.35 1.3 Jamón curado molde cuadrado sin piel / Skinned cured ham in a 7.8 Cabeza / Head......................................................................p.35 -

EVENTS MENU TABLE of CONTENTS

2018 INSPIRING EVENT MENUS EVENTS MENU TABLE of CONTENTS Breakfast – Hot Buffet ......................................................................... 2 Breakfast – Continental ....................................................................... 5 Breakfast – Plated ................................................................................ 6 Breakfast - Enhancements ................................................................... 6 Coffee Breaks ........................................................................................ 7 Lunch – Buffet ........................................................................................ 9 Lunch – Hot Buffet ................................................................................. 11 Lunch – à la Carte ................................................................................... 13 Reception ................................................................................................ 16 Dinner – Buffet ....................................................................................... 21 Dinner – à la Carte ................................................................................. 26 Bar – Beverage ....................................................................................... 32 Marriott Downtown at CF Toronto Eaton Centre | 525 Bay Street Toronto Ontario M5G 2L2 Canada | +1-416-597-9200 1 | P a g e N O T E : G F – Gluten Friendly, DF – Dairy Friendly 13.68% gratuity, 4.32% facility fee & 13% HST will apply. Prices & menus are subject -

Gourmet Express

Explore the Train The majority of the cars on the Napa Valley Wine Train’s consist were built in 1915 by the Pullman Standard Company as first class coaches for the Northern Pacific Railway for use on their premiere trains, the North Coast Limited and the Northern Pacific Atlantic Express. They were the height of technological advancement for their time and were built entirely out of steel. An all steel car provided significant improvements in safety to rail travelers. Other amenities of the newly built cars included electric lights, steam heat, and arched windows. The steel cars, also known as heavyweights, were Gourmet significantly heavier than their wood predeces- sors, which each weighed about 141,000 pounds or Express 70.5 tons, and were around 83 feet long. In 1960, the Denver Rio Grande Western Railroad bought several of these Northern Pacific cars for its Ski Train service from Denver to Winter Park. They remained in service on the Denver Ski Train until they were purchased by the Napa Valley Wine Train in 1987. After acquiring them, the Napa Val- ley Wine Train began an extensive restoration project to restore and re imagine the cars. The cars were furnished with Honduran mahogany pan- eling, brass accents, etched glass partitions, and velveteen fabric armchairs. Great effort was exerted to ensure that the interior of the railcars evoked the spirit of opulent rail travel at the beginning of the twentieth century. First CHEF’S DAILY SOUP INSPIRATION TRAIN MAP TO CALISTOGA SONOMA MIXED GREENS sky hill farms goat cheese, shaved fennel, CASTELLO DI CHARLES KRUG AMOROSA roasted grapes, toasted almonds, MERRYVALE champagne-dijon vinaigrette LOUIS MARTINI BERINGER V. -

Salads Appetizers

Serving Time: 13:00 – 22:00 (Last orders 21:30) Salads Greek salad with cherry tomatoes, feta cheese, cucumber, onion, green pepper 7€ capers, olives and garlic-feta vinaigrette Colorful salad with cherry tomatoes, “graviera” cheese from Crete and marinated “apaki” 8€ smoked pork from Mani, browned caper and pine nuts with balsamic and honey vinaigrette Fresh vegetables with breaded chicken, roasted sesame with yogurt vinaigrette 10€ Cycladic rocket leaves salad with small toasted bread, “kopanisti” cheese from Mykonos 9€ and “louza” cured meat from Tinos Pandaisia salad with smoked salmon, cherry tomatoes, lemon and fresh onion vinaigrette 10€ Appetizers Variety of Santorini tomato and zucchini dumplings served with feta and herbs mousse 7€ Fried feta cheese with “rakomelo” from Crete and roasted pine nuts 7€ Variety of handmade traditional pies 8€ (spinach pie, cheese pie, “kaseri” cheese and “pastourma” pie) Traditional Santorini “fava” (split peas) with fried capers, and anchovy fillets 7€ Smoked salmon millefeuille with crust, caramelized onions and spinach 11€ Shrimp mousse wrapped in phyllo pastry with sweet and sour Greek sauce 10€ Main Courses Rib eye “Black Angus” with shrimp sauce served with vegetable macrame 28€ Greek meze (variety of grilled meat and pita bread with tzatziki dip) 15€ Grilled chicken fillet with aromatic marjoram sauce and feta cheese and garlic 16€ Greek style burger served with country style fried potatoes and homemade ketchup 12€ Risotto with mushrooms and “syglino” smoked pork from Mani flavored with -

Hank You! for Considering the Mockingbird’S Miraval Ballroom As a Place to Host Your Event

hank you! for considering The Mockingbird’s Miraval Ballroom as a place to host your event. We would love to T assist you in creating a memorable experience for you & your guests Starters ………………... Dinner Entrées ………………………………….. Please Select One Please select one entrée. Two entrée selections are available for an additional $3.00 per person. Caesar Salad House Salad Seared Chicken Piccata Baby Field Green Salad with Lemon, Mushrooms, Parsley with White Butter Sauce ……….$ 27.95 Soup of the Day Slow Roasted Prime Rib of Beef Seasonal Fresh Fruit with Classic Aujus ……….$ 34.95 Or for an additional 1.50 p.p. Stuffed Haddock Clam Chowder or Greek Salad with our Seafood Stuffing ……….$ 28.95 Grilled 8 ounce Filet Mignon Dessert ………………………….. Dinner rolls and butter with Gorgonzola Maître d’ Butter ……….$ 40.95 Please Select One are served with your starter course Baked Stuffed Jumbo Shrimp Cheesecake with Seasonal Fresh Fruit with our Seafood Stuffing ……….$ 33.95 Chocolate Overload Mousse Cake Accompaniments …… Chicken with Prosciutto de Parma Amaretto Mousse Served in a Martini Please Select Two Steamed Spinach, Melted Asiago Cheese & Garlic Butter Sauce ……….$ 29.95 Glass with Straw Cookie Roasted Pork Loin with Rosemary Plum Crust Tiramisu Roasted Rosemary Potato over a Sweet Soy & Ginger Infused Gravy ……….$ 29.95 Seasonal Selections are also available Garlic Mashed Potato Sautéed Seasonal Vegetables Medley Chicken Saltimbocca Baby Carrots with Herb Butter with Prosciutto de Parma, Fontina Cheese & Custom Personalized Cakes Mashed Sweet Potato Mushrooms in a Madeira Demi Glace ……….$ 29.95 Roasted Butternut Squash are available with proper notice Apple Corn Bread & Sun Dried Cranberry Stuffed Chicken Steamed Cauliflower with Supreme sauce ……….$ 27.95 Rice Pilaf Green Beans Statler Chicken Breast Beverages……………………..