Musica Scotica Retroproceedings MASTER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Bartlett, T. (2020) Time, the Deer, Is in the Wood: Chronotopic Identities, Trajectories of Texts and Community Self-Management

Bartlett, T. (2020) Time, the deer, is in the wood: chronotopic identities, trajectories of texts and community self-management. Applied Linguistics Review, (doi: 10.1515/applirev-2019-0134). This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/201608/ Deposited on: 24 October 2019 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Tom Bartlett Time, the deer, is in the wood: Chronotopic identities, trajectories of texts and community self-management Abstract: This paper opens with a problematisation of the notion of real-time in discourse analysis – dissected, as it is, as if time unfolded in a linear and regular procession at the speed of speech. To illustrate this point, the author combines Hasan’s concept of “relevant context” with Bakhtin’s notion of the chronotope to provide an analysis of Sorley MacLean’s poem Hallaig, with its deep-rootedness in space and its dissolution of time. The remainder of the paper is dedicated to following the poem’s metamorphoses and trajectory as it intertwines with Bartlett’s own life and family history, creating a layered simultaneity of meanings orienting to multiple semio-historic centres. In this way the author (pers. comm.) “sets out to illustrate in theory, text analysis and (self-)history the trajectories taken by texts as they cross through time and space; their interconnectedness -

Reel of the 51St Division

Published by the LONDON BRANCH of the ROYAL SCOTTISH COUNTRY DANCE SOCIETY www. rscdslondon.org.uk Registered Charity number 1067690 Dancing is FUN! No 260 MAY to AUGUST 2007 ANNUAL GENERAL SUMMER PICNIC DANCE MEETING In the Grounds of Harrow School The AGM of the Royal Scottish Country Saturday 30 June 2007 from 2.00-6.00pm. Dancing to David Hall and his Band Dance Society London Branch will be held at The nearest underground station is Harrow on the Hill. St Columba's Church (Upper Hall), Pont Programme Harrow School is 10 to 15 minutes walk east along Street, London, SWI on Friday 15 June 2007. The Dashing White Sergeant .............. 2/2 Lowlands Road (A404) and then right into Peterborough Tea will be served at 6pm and the meeting will The Happy Meeting ......................... 29/9 Road to Garlands Lane, first on left. The 258 bus from commence at 7pm. There will be dancing after Monymusk ...................................... 11/2 Harrow on the Hill tube station heading towards South the meeting. The White Cockade ......................... 5/11 Harrow drops passengers just below Garlands Lane – it’s AGENDA Neidpath Castle ............................... 22/9 about a 5 min ride. The same bus travels from South 1 Apologies. The Wild Geese .............................. 24/3 Harrow tube station also past Garlands Lane. (Note that 2 Approval of minutes of the 2006 AGM. The Reel of the 51st Division ....... 13/10 the fare is £2 now for any length of journey.) Taxis are 3 Business arising from the minutes. The Braes of Breadalbane ................ 21/7 available from the station. Ample car parking is available 4 Report on year's working of the Branch. -

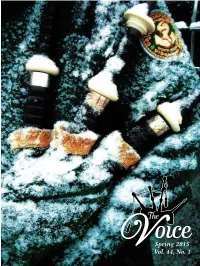

Spring 2015 Vol. 44, No. 1 Table of Contents

Spring 2015 Vol. 44, No. 1 Table of Contents 4 President’s Message Music 5 Editorial 33 Jimmy Tweedie’s Sealegs 6 Letters to the Editor 43 Report for the Reviews Executive Secretary 34 Review of Gibson Pipe Chanter Spring 2015 35 The Campbell Vol. 44, No. 1 Basics Tunable Chanter 9 Snare Basics: Snare FAQ THE VOICE is the official publication of the Eastern United 11 Bass & Tenor Basics: Semiquavers States Pipe Band Association. Writing a Basic Tenor Score 35 The Making of the 13 Piping Basics: “Piob-ogetics” Casco Bay Contest John Bottomley 37 Pittsburgh Piping EDITOR [email protected] Features Society Reborn 15 Interview Shawn Hall 17 Bands, Games Come Together Branch Notes ART DIRECTOR 19 Willie Wows ‘Em 39 Southwest Branch [email protected] 21 The Last Happy Days – 39 Metro Branch Editorial Inquiries/Letters the Great Highland Bagpipe 40 Ohio Valley Branch THE VOICE in JFK’s Camelot 41 Northeast Branch [email protected] ADVERTISING INQUIRIES John Bottomley [email protected] THE VOICE welcomes submissions, news items, and ON THE COVER: photographs. Please send your Derek Midgley captured the joy submissions to the email above. of early St. Patrick’s parades in the northeast with this photo of Rich Visit the EUSPBA online at www.euspba.org Harvey’s pipe at the Belmar NJ event. ©2014 Eastern United States Pipe Band EUSPBA MEMBERS receive a subscription to THE VOICE paid for, in part, Association. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced or transmitted by their dues ($8 per member is designated for THE VOICE). -

Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 3-1995 Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music Matthew S. Emmick Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Emmick, Matthew S., "Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music" (1995). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 21. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/21 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM Honors Thesis Certification Matthew S. Emmick Applicant (Name as It Is to appear on dtplomo) Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle M'-Isic Thesis title _ May, 1995 lnter'lded date of commencemenf _ Read and approved by: ' -4~, <~ /~.~~ Thesis adviser(s)/ /,J _ 3-,;13- [.> Date / / - ( /'--/----- --",,-..- Commltte~ ;'h~"'h=j.R C~.16b Honors t-,\- t'- ~/ Flrst~ ~ Date Second Reader Date Accepied and certified: JU).adr/tJ, _ 2111c<vt) Director DiJe For Honors Program use: Level of Honors conferred: University Magna Cum Laude Departmental Honors in Music and High Honors in Spanish Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music A Thesis Presented to the Departmt!nt of Music Jordan College of Fine Arts and The Committee on Honors Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Matthew S. Emmick March, 24, 1995 -l _ -- -"-".,---. -

Sheila Stewart

Sheila, Belle and Jane Turriff. Photo: Alistair Chafer “…Where would Sheila Stewart the ballad singing Scottish Traveller, Traditional Singer and Storyteller tradition in Scotland 1935 - 2014 be today without the unbroken continuity by Pete Shepheard of tradition passed on to us by Sheila and other members of Scotland’s ancient Traveller community…” “…one of Scotland’s finest traditional singers, inheriting The family was first brought to When berry time comes roond look for the Stewarts who rented Traveller lore and balladry from all light by Blairgowrie journalist each year, Blair’s population’s berry fields at the Standing Stones sides of her family, and learning a rich oral culture Maurice Fleming in 1954 following swellin, at Essendy. So he cycled up to songs from her mother, some of a chance meeting with folklorist There’s every kind o picker there Essendy and it was Sheila Stewart the most interesting, and oldest, of songs, ballads Hamish Henderson in Edinburgh. and every kind o dwellin; he met (just 18 years old at the songs in her repertoire came from Discovering that Hamish had There’s tents and huts and time) who immediately said she Belle’s brother, her uncle, Donald caravans, there’s bothies and and folk tales that recently been appointed as a knew the song and told Maurice MacGregor, who carefully taught there’s bivvies, research fellow at the School it had been written by her mother her the ballads. Donald could had survived as And shelters made wi tattie-bags Belle. Maurice reported the of Scottish Studies, Maurice neither read nor write, but was an and dug-outs made wi divvies. -

Suggested Repertoire

THE LEINSTER SCHOOL OF RATE YOUR ABILITY REPERTOIRE LIST MUSIC & DRAMA Level 1 Repertoire List Bog Down in the Valley Garryowen Polka Level 2 Repertoire List Maggie in the Woods Planxty Fanny Power Level 3 Repertoire List Jigs Learn to Play Irish Trad Fiddle The Kesh Jig (Tom Morley) The Hag’s Purse Blarney Pilgrim The Merry Blacksmith The Swallowtail Jig Tobin’s Favourite Double Jigs: (two, and three part jigs) The Hag at the Churn I Buried My Wife and Danced on her Grave The Carraroe Jig The Bride’s Favourite Saddle the Pony Rambling Pitchfork The Geese in the Bog (Key of C or D) The Lilting Banshee The Mist Covered Meadow (Junior Crehan Tune) Strike the Gay Harp Trip it Upstairs Slip Jigs: (two, and three part jigs) The Butterfly Éilish Kelly’s Delight Drops of Brandy The Foxhunter’s Deirdre’s Fancy Fig for a Kiss The Snowy Path (Altan) Drops of Spring Water Hornpipes Learn to Play Irish Trad Fiddle Napoleon Crossing the Alps (Tom Morley) The Harvest Home Murphys Hornpipes: (two part tunes) The Boys of Bluehill The Homeruler The Pride of Petravore Cornin’s The Galway Hornpipe Off to Chicago The Harvest Home Slides Slides (Two and three Parts) The Brosna Slides 1&2 Dan O’Keefes The Kerry Slide Merrily Kiss the Quaker Reels Learn to Play Irish Trad Fiddle The Raven’s Wing (Tom Morley) The Maid Behind the Bar Miss Monaghan The Silver Spear The Abbey Reel Castle Kelly Reels: (two part reels) The Crooked Rd to Dublin The Earl’s Chair The Silver Spear The Merry Blacksmith The Morning Star Martin Wynne’s No 1 Paddy Fahy’s No 1 Fr. -

QH 40Th Anniversary Press Release

EMBARGOED TILL 5/11/18 at midday THE QUEEN’S HALL – LIFE BEGINS AT 40 1979-2019: Former church celebrates 40 years of welcoming music worshippers through its doors Southside of the Tracks 12.01.19 Steven Osborne & Alban Gerhardt 06.07.19 The Queen’s Hall enters its fortieth year in 2019 with a packed and varied programme of high quality events which reflect the wealth of entertainment it has provided audiences over the years, whilst also looking forward to a bright future. The celebrations start on 12 January with a who’s who of singer-songwriters brought together on the same stage for the first time by Scotland’s foremost fiddle player, John McCusker. Renowned for his skill at transcending musical boundaries, John has shared stages with Paul Weller, Paolo Nutini and Teenage Fanclub and has been a member of Mark Knopfler’s house band since 2008. In Southside of the Tracks: 40 years of traditional music at The Queen’s Hall he will perform with his chosen house band of James Mackintosh, Ian Carr, Ewen Vernal, Michael McGoldrick and Louis Abbott (Admiral Fallow) with special guests, so far, Roddy Woomble (Idlewild), Kathleen MacInnes, Phil Cunningham, Adam Holmes, Daoiri Farrell, Heidi Talbot and Rachel Sermanni. More guests are to be announced. Nigel Griffiths, Chair of The Queen’s Hall Board of Trustees says, “We’re starting our fortieth year as we mean to go on and have a bold and ambitious programme which reflects the calibre of artists performing on our stage. In the face of developing competition it is so important for Edinburgh, as the capital city, to keep this beloved institution on the map and I believe we’re now poised to enter a truly dynamic era in The Queen’s Hall’s history.” To commemorate the concert on 6 July 1979 when The Queen’s Hall was officially opened by HM Queen Elizabeth II, we have multi-award-winning Scottish pianist Steven Osborne with one of the world’s finest cellists Alban Gerhardt performing a programme of Schumann, Brahms, De falla, Debussy and Ravel. -

Teaching Scottish Country Dancing

GUIDELINES FOR TEACHING SCOTTISH COUNTRY DANCING CONTENTS Foreword ......................................................................... i Acknowledgements ......................................................................... ii Definitions ......................................................................... iii Introduction ......................................................................... 1 Theory (Unit 1) ......................................................................... 1 Practical Dancing (Unit 2) ......................................................................... 2 Warm-ups and Cool Downs ......................................................................... 4 Teaching – Level 1 (Unit 3) ......................................................................... 4 Teaching Practice (Unit 4) ......................................................................... 8 Teaching – Level 2 (Unit 5) ......................................................................... 8 Teaching Elements ......................................................................... 9 Steps and Formations ......................................................................... 9 Build up of the dance ......................................................................... 10 Observation ......................................................................... 10 Presentation ......................................................................... 12 Class Management ........................................................................ -

Seist Chorus Sections in Scottish Gaelic Song: an Overview of Their Evolving Uses and Functions

Seist Chorus Sections in Scottish Gaelic Song: An Overview of Their Evolving Uses and Functions by Anna Wright BMus, Edinburgh Napier University, 2015 MMus, University of British Columbia, 2018 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Ethnomusicology) The University of British Columbia (Vancouver) April 2020 © Anna Wright, 2020 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the thesis entitled: Seist Chorus Sections in Scottish Gaelic Song: An Overview of Their Evolving Uses and Functions submitted by Anna Wright in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Ethnomusicology Examining Committee: Nathan Hesselink Supervisor, Chair, Ethnomusicology Department, School of Music, UBC Michael Tenzer Supervisory Committee Member, Professor, Ethnomusicology Department, School of Music, UBC ii Abstract This thesis examines the use of seist chorus sections in the Scottish Gaelic song tradition. These sections consist of nonsense syllables, or vocables. Although lacking semantic meaning, such vocables often provoke the joining in of the audience or listening group. The use of these vocable sections can be seen to have evolved in both their physical (sonic) characteristics and their social use and function over time while still maintaining a marked presence in Scottish Gaelic music across many genres and generations. I briefly examine theories surrounding seist vocables’ inception, interview three practitioners of Gaelic song about seist choruses’ inception and evolving function, examine four songs dating from a period spanning 1601-2016, and relate my findings to Scotland’s constantly evolving social and political climate. -

The Musicians______

The musicians_______________________________________________________________________ Ross Ainslie Bagpipes & Whistle Ross hails from Bridge of Earn in Perthshire. He began playing chanter at the age of 8 and like Ali Hutton studied under the watchful eye of the late great Gordon Duncan and was a member of the Vale of Atholl pipe band. Ross also plays with Salsa Celtica, Dougie Maclean's band, India Alba, Tunebook, Charlie Mckerron's trio and in a duo with Irish piper Jarlath Henderson. He released his début solo album "Wide Open" in 2013 which was voted 9th out of 50 in the Sunday Herald "The Scottish albums of 2013". He was nominated for "musician of the year" at the Radio 2 folk awards 2013 and also for "Best Instrumentalist" at the Scots Trad Music Awards in 2010 and 2012. Ali Hutton Bagpipes & Whistle Ali, from Methven in Perthshire, was inspired at the age of 7 to take up the bagpipes and came up through the ranks at the Vale of Atholl pipe band. He was taught alongside Ross Ainslie by the late, great Gordon Duncan and has gone on to become a successful multi‐instrumentalist on the Scottish music scene. He has produced and co‐produced several albums such as Treacherous Orchestra’s “Origins”, Maeve Mackinnon's “Don't sing love songs”, The Long Notes’ “In the Shadow of Stromboli” and Old Blind Dogs’ “Wherever Yet May Be”. Ali is also currently a member of Old Blind Dogs and the Ross Ainslie band but has played with Capercaillie, Deaf Shepherd, Emily Smith Band, Dougie Maclean, Back of the Moon and Brolum amongst many others. -

Thesis&Preparation&Appr

THESIS&PREPARATION&APPROVAL&FORM& & Title&of&Thesis:& Scottish&Fiddling&in&the&United&States:&Reviving&a&Tradition&and&Maintaining&a&Community& & & I. To&be&completed&by&the&Student:& & I&certify&that&this&document&meets&the&preparation&guidelines&as&presented&in&the& Style&Guide&and&Instructions&for&Preparing&Theses&and&Dissertations.&& & & _________________________________& &_______________& (Signature&of&Student)&& & (Date)& & & II. To&be&completed&by&thesis&advisor:& & I&certify&that&this&document&is&suitable&for&submission.& & & _________________________________&& _______________& (Signature&of&Advisor)&& & (Date)& & III. To&be&completed&by&School&Director:& & I&certify,&to&the&best&of&my&knowledge,&that&the&required&procedures&have&been& followed&and&the&preparation&criteria&have&been&met&for&this&thesis/dissertation.&& & & _________________________________& &_______________& (Signature&of&Director)&& & (Date)& & & xc:&Graduate&Coordinator& SCOTTISH FIDDLING IN THE UNITED STATES: REVIVING A TRADITION AND MAINTAINING A COMMUNITY A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By Deanna T. Nebel May, 2015 Thesis written by Deanna T. Nebel B.M., Westminster College, 2013 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Jennifer Johnstone, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Ralph Lorenz, Ph.D., Acting Director, School of Music ____________________________________________________