The Name of the Hwicce: a Discussion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE KINGDOM and COINS of BURGRED. HE Anglo-Saxon

THE KINGDOM AND COINS OF BURGRED. BY NATHAN HEYWOOD. HE Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia became tributary to Egbert, King of Wessex, on the death of Ludica, A.D. 825, and was afterwards governed successively by Wiglaf, 825-839 ; Bertulf, 839-852 ; and Burgred, 852-874. Burgred married Aethelswith, a daughter of Ethelwlf, King of Wessex, grand- daughter <if Egbert, and the sister of Ethelred I. and Alfred the Great, successive kings of Wessex.1 When Burgred came to the throne the Danes were in occupation of southern Mercia,3 but during the first year of his reign they were driven out by ^Fkhelwlf and the West Saxons, who thereupon joined the Mercian forces, under the personal command of Burgred, in subduing the Welsh.3 Having at length obtained complete possession of his dominions he ruled in peace until 866, when the Danes in overwhelming numbers invaded East Anglia and wintered o o there.4 In the following year, 867, the enemy commenced the campaign 1 " And upon this [subjugation of North-Welsh] after Easter Ethelwlf, King of West Saxons, gave his daughter to Burgred, King of Mercia." Sax. Ch. 14. 2 " And the same year (851) came three hundred and forty ships to Thames mouth and the crews landed and broke into Canterbury and London, and put to flight Beorhtwulf, King of the Mercians, with his army." Sax. Ch. 12. 3 " Here Burhred, King of the Mercians, and his witan begged of King yEthelwlf that he would assist him so that he might make the North-Welsh obedient to him. -

Joint Cabinet Crisis Kingdom of Mercia

Joint Cabinet Crisis Kingdom of Mercia Hamburg Model United Nations “Shaping a New Era of Diplomacy” 28th November – 1st December 2019 JCC – Kingdom of Mercia Hamburg Model United Nations Study Guide 28th November – 1st December Welcome Letter by the Secretary Generals Dear Delegates, we, the secretariat of HamMUN 2019, would like to give a warm welcome to all of you that have come from near and far to participate in the 21st Edition of Hamburg Model United Nations. We hope to give you an enriching and enlightening experience that you can look back on with joy. Over the course of 4 days in total, you are going to try to find solutions for some of the most challenging problems our world faces today. Together with students from all over the world, you will hear opinions that might strongly differ from your own, or present your own divergent opinion. We hope that you take this opportunity to widen your horizon, to, in a respectful manner, challenge and be challenged and form new friendships. With this year’s slogan “Shaping a New Era of Democracy” we would like to invite you to engage in and develop peaceful ways to solve and prevent conflicts. To remain respectful and considerate in diplomatic negotiations in a time where we experience our political climate as rough, and to focus on what unites us rather than divides us. As we are moving towards an even more globalized and highly military armed world, facing unprecedented threats such as climate change and Nuclear Warfare, international cooperation has become more important than ever to ensure peace and stability. -

Appendix Eight

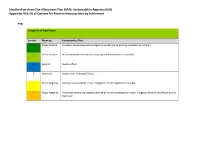

Stratford-on-Avon Site Allocations Plan (SAP): Sustainability Appraisal (SA) Appendix VIII: SA of Options for Reserve Housing Sites by Settlement Key: Categories of Significance Symbol Meaning Sustainability Effect ++ Major Positive Proposed development encouraged as would resolve existing sustainability problem + Minor Positive No sustainability constraints and proposed development acceptable 0 Neutral Neutral effect ? Uncertain Uncertain or Unknown Effects - Minor Negative Potential sustainability issues: mitigation and/or negotiation possible -- Major Negative Problematical and improbable because of known sustainability issues; mitigation likely to be difficult and/or expensive Alcester Settlement Baseline Overview relevant to SA objectives: SA Objective Settlement Assessment Heritage The historic market town of Alcester overlies the site of a significant Roman settlement on Icknield Street. The town was granted a Royal Charter to hold a weekly market in 1274 and prospered throughout the next centuries. In the 17th Century it became a centre of the needle industry. With its long narrow Burbage plots and tueries (interlinking passageways), the town centre street pattern of today and many of its buildings are medieval. There are a number of heritage assets which includes Scheduled Monuments, Listed Buildings, a Conservation Area and archaeological features within and adjacent to the urban area. The Conservation area’s character is defined by the medieval street pattern, the presence of a wide diversity of buildings with a range of distinguishing features, and the gaps between the buildings which create an intriguing spatial element. The majority of Alcester’s Listed Buildings are located within the Conservation Area, as are parts of the Alcester Roman Town Scheduled Monument.1 Landscape The Landscape Sensitivity Study identifies extensive areas of land adjacent to the town as being of high sensitivity to development. -

Wessex and the Reign of Edmund Ii Ironside

Chapter 16 Wessex and the Reign of Edmund ii Ironside David McDermott Edmund Ironside, the eldest surviving son of Æthelred ii (‘the Unready’), is an often overlooked political figure. This results primarily from the brevity of his reign, which lasted approximately seven months, from 23 April to 30 November 1016. It could also be said that Edmund’s legacy compares unfavourably with those of his forebears. Unlike other Anglo-Saxon Kings of England whose lon- ger reigns and periods of uninterrupted peace gave them opportunities to leg- islate, renovate the currency or reform the Church, Edmund’s brief rule was dominated by the need to quell initial domestic opposition to his rule, and prevent a determined foreign adversary seizing the throne. Edmund conduct- ed his kingship under demanding circumstances and for his resolute, indefati- gable and mostly successful resistance to Cnut, his career deserves to be dis- cussed and his successes acknowledged. Before discussing the importance of Wessex for Edmund Ironside, it is con- structive, at this stage, to clarify what is meant by ‘Wessex’. It is also fitting to use the definition of the region provided by Barbara Yorke. The core shires of Wessex may be reliably regarded as Devon, Somerset, Dorset, Wiltshire, Berk- shire and Hampshire (including the Isle of Wight).1 Following the victory of the West Saxon King Ecgbert at the battle of Ellendun (Wroughton, Wilts.) in 835, the borders of Wessex expanded, with the counties of Kent, Sussex, Surrey and Essex passing from Mercian to West Saxon control.2 Wessex was not the only region with which Edmund was associated, and nor was he the only king from the royal House of Wessex with connections to other regions. -

The Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Mercia and the Origins and Distribution of Common Fields*

The Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia and the origins and distribution of common fields* by Susan Oosthuizen Abstract: This paper aims to explore the hypothesis that the agricultural layouts and organisation that had de- veloped into common fields by the high middle ages may have had their origins in the ‘long’ eighth century, between about 670 and 840 AD. It begins by reiterating the distinction between medieval open and common fields, and the problems that inhibit current explanations for their period of origin and distribution. The distribution of common fields is reviewed and the coincidence with the kingdom of Mercia noted. Evidence pointing towards an earlier date for the origin of fields is reviewed. Current views of Mercia in the ‘long’ eighth century are discussed and it is shown that the kingdom had both the cultural and economic vitality to implement far-reaching landscape organisation. The proposition that early forms of these field systems may have originated in the ‘long’ eighth century is considered, and the paper concludes with suggestions for further research. Open and common fields (a specialised form of open field) endured in the English landscape for over a thousand years and their physical remains still survive in many places. A great deal is known and understood about their distribution and physical appearance, about their man- agement from their peak in the thirteenth century through the changes of the later medieval and early modern periods, and about how and when they disappeared. Their origins, however, present a continuing problem partly, at least, because of the difficulties in extrapolating in- formation about such beginnings from documentary sources and upstanding earthworks that record – or fossilise – mature or even late field systems. -

Environment Agency Midlands Region Wetland Sites Of

LA - M icllanAs <? X En v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y ENVIRONMENT AGENCY MIDLANDS REGION WETLAND SITES OF SPECIAL SCIENTIFIC INTEREST REGIONAL MONITORING STRATEGY John Davys Groundwater Resources Olton Court July 1999 E n v i r o n m e n t A g e n c y NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House. Goldhay Way. Orton Goldhay, Peterborough PE2 5ZR 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................... 3 1.) The Agency's Role in Wetland Conservation and Management....................................................3 1.2 Wetland SSSIs in the Midlands Region............................................................................................ 4 1.3 The Threat to Wetlands....................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 Monitoring & Management of Wetlands...........................................................................................4 1.5 Scope of the Report..............................................................................................................................4 1.6 Structure of the Report.......................................................................................................................5 2 SELECTION OF SITES....................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Definition of a Wetland Site................................................................................................................7 -

Deadly Hostility: Feud, Violence, and Power in Early Anglo-Saxon England

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2017 Deadly Hostility: Feud, Violence, and Power in Early Anglo-Saxon England David DiTucci Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation DiTucci, David, "Deadly Hostility: Feud, Violence, and Power in Early Anglo-Saxon England" (2017). Dissertations. 3138. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3138 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEADLY HOSTILITY: FEUD, VIOLENCE, AND POWER IN EARLY ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND by David DiTucci A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy History Western Michigan University June 2017 Doctoral Committee: Robert F. Berkhofer III, Ph.D., Chair Jana Schulman, Ph.D. James Palmitessa, Ph.D. E. Rozanne Elder, Ph.D. DEADLY HOSTILITY: FEUD, VIOLENCE, AND POWER IN EARLY ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND David DiTucci, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2017 This dissertation examines the existence and political relevance of feud in Anglo-Saxon England from the fifth century migration to the opening of the Viking Age in 793. The central argument is that feud was a method that Anglo-Saxons used to understand and settle conflict, and that it was a tool kings used to enhance their power. The first part of this study examines the use of fæhð in Old English documents, including laws and Beowulf, to demonstrate that fæhð referred to feuds between parties marked by reciprocal acts of retaliation. -

The Demo Version

Æbucurnig Dynbær Edinburgh Coldingham c. 638 to Northumbria 8. England and Wales GODODDIN HOLY ISLAND Lindisfarne Tuidi Bebbanburg about 600 Old Melrose Ad Gefring Anglo-Saxon Kingdom NORTH CHANNEL of Northumbria BERNICIA STRATHCLYDE 633 under overlordship Buthcæster Corebricg Gyruum * of Northumbria æt Rægeheafde Mote of Mark Tyne Anglo-Saxon Kingdom Caerluel of Mercia Wear Luce Solway Firth Bay NORTHHYMBRA RICE Other Anglo-Saxon united about 604 Kingdoms Streonæshalch RHEGED Tese Cetreht British kingdoms MANAW Hefresham c 624–33 to Northumbria Rye MYRCNA Tribes DEIRA Ilecliue Eoforwic NORTH IRISH Aire Rippel ELMET Ouse SEA SEA 627 to Northumbria æt Bearwe Humbre c 627 to Northumbria Trent Ouestræfeld LINDESEGE c 624–33 to Northumbria TEGEINGL Gæignesburh Rhuddlan Mærse PEC- c 600 Dublin MÔN HOLY ISLAND Llanfaes Deganwy c 627 to Northumbria SÆTE to Mercia Lindcylene RHOS Saint Legaceaster Bangor Asaph Cair Segeint to Badecarnwiellon GWYNEDD WREOCAN- IRELAND Caernarvon SÆTE Bay DUNODING MIERCNA RICE Rapendun The Wash c 700 to Mercia * Usa NORTHFOLC Byrtun Elmham MEIRIONNYDD MYRCNA Northwic Cardigan Rochecestre Liccidfeld Stanford Walle TOMSÆTE MIDDIL Bay POWYS Medeshamstede Tamoworthig Ligoraceaster EAST ENGLA RICE Sæfern PENCERSÆTE WATLING STREET ENGLA * WALES MAGON- Theodford Llanbadarn Fawr GWERTH-MAELIENYDD Dommoceaster (?) RYNION RICE SÆTE Huntandun SUTHFOLC Hamtun c 656 to Mercia Beodericsworth CEREDIGION Weogornaceaster Bedanford Grantanbrycg BUELLT ELFAEL HECANAS Persore Tovecestre Headleage Rendlæsham Eofeshamm + Hereford c 600 GipeswicSutton Hoo EUIAS Wincelcumb to Mercia EAST PEBIDIOG ERGING Buccingahamm Sture mutha Saint Davids BRYCHEINIOG Gleawanceaster HWICCE Heorotford SEAXNA SAINT GEORGE’SSaint CHANNEL DYFED 577 to Wessex Ægelesburg * Brides GWENT 628 to Mercia Wæclingaceaster Hetfelle RICE Ythancæstir Llanddowror Waltham Bay Cirenceaster Dorchecestre GLYWYSING Caerwent Wealingaford WÆCLINGAS c. -

Warwickshire

CD Warwickshire 7 PUBLIC TRANSPORT MAP Measham Newton 7 Burgoland 224 Snarestone February 2020 224 No Mans Heath Seckington 224 Newton Regis 7 E A B 786 Austrey Shackerstone 785 Twycross 7 Zoo 786 Bilstone 1 15.16.16A.X16 785 Shuttington 48.X84.158 224 785 Twycross 7 Congerstone 216.224.748 Tamworth 786 Leicester 766.767.785.786 Tamworth Alvecote 785 Warton 65 Glascote Polesworth 158 1 Tamworth 786 Little LEICESTERSHIRELEICESTERSHIRE 48 Leicester Bloxwich North 65 65 65.766.767 7 Hospital 16 748 Warton 16A 766 216 767 Leicester 15 Polesworth Forest East Bloxwich STAFFORDSHIRES T A F F O R D S H I R E 785 X84 Fazeley 766 16.16A 786 Birchmoor 65.748 Sheepy 766.767 Magna Wilnecote 786 41.48 7 Blake Street Dosthill Dordon 766.767 761.766 158 Fosse Park Birch Coppice Ratcliffe Grendon Culey 48 Butlers Lane 216 15 Atherstone 65. X84 16 761 748. 7 68 7 65 Atterton 16A 766.76 61 68 ©P1ndar 15 ©P1ndar 7 ©P1ndar South Walsall Wood 7.65 Dadlington Wigston Middleton Baddesley 761 748 Stoke Four Oaks End .767 Witherley Golding Ensor for details 7 Earl Shilton Narborough 15 in this area Mancetter 7 Baxterley see separate Hurley town centre map 41 68 7 Fenny Drayton Bescot 75 216 Common 228 7 Barwell Stadium 16.16A 65 7.66 66 66 X84 WESTWEST Sutton Coldfield 216 15 Kingsbury 228 68 68 65 Higham- 158 Allen End Hurley 68 65 223 66 MIRA on-the-Hill 48 Bodymoor 15 15 Bentley 41 Ridge Lane 748 Cosby 767 for details in this area see Tame Bridge MIDLANDSMIDLANDS 216 Heath separate town centre map Wishaw Marston Hartshill 66 65. -

Aethelflaed of Wessex Aethelstan

amongst some of the normally more divisive Celts. Aethelflaed of The kingdom of Ulster, in particular, is friendly to Wessex (Ae-thel-flaad) her and regularly lauds her greatness. Famosissima Regina Saxonum, Her political maneuverings are coming near to a “The Great Lady of the Saxons” point where she may take up arms against King Aethelstan, in spite of their history. Tensions Mercia, Angeland in Britain between her and Aethelstan have been rising as he has sought further lands to control, while she Aethelflaed may be a queen but with her mousy supports the continued existence of many small- brown hair, pale skin, and plain-looking, er Kingdoms across the Isles. Many of the Cymry dull-coloured clothes, she does not look the part. kings and lords would happily pledge their lives to To look upon her it would not be surprising to her in exchange for a less strict overlordship. see her working the fields or tending to animals amongst her people. Despite appearances, she has a cunning eye and is adept at the political halls of (Ethel-stan) power. Under her humble clothes, she conceals a Aethelstan knife that can be planted in the back of her enemies King of Wessex should the need arise. All this is in spite of her rel- Winchester, Wessex, Angleland in Britain atively advanced age, having fostered Aethelstan and been an important figure throughout the isles. King Aethelstan rules from his seat of power in Renowned by the Cymry and those of Ulster as Winchester, Wessex. He is the head of the “White a powerful Saxon queen, many would prefer to God army” that has invaded the Isles. -

'J.E. Lloyd and His Intellectual Legacy: the Roman Conquest and Its Consequences Reconsidered' : Emyr W. Williams

J.E. Lloyd and his intellectual legacy: the Roman conquest and its consequences reconsidered,1 by E.W. Williams In an earlier article,2 the adequacy of J.E.Lloyd’s analysis of the territories ascribed to the pre-Roman tribes of Wales was considered. It was concluded that his concept of pre- Roman tribal boundaries contained major flaws. A significantly different map of those tribal territories was then presented. Lloyd’s analysis of the course and consequences of the Roman conquest of Wales was also revisited. He viewed Wales as having been conquered but remaining largely as a militarised zone throughout the Roman period. From the 1920s, Lloyd's analysis was taken up and elaborated by Welsh archaeology, then at an early stage of its development. It led to Nash-Williams’s concept of Wales as ‘a great defensive quadrilateral’ centred on the legionary fortresses at Chester and Caerleon. During recent decades whilst Nash-Williams’s perspective has been abandoned by Welsh archaeology, it has been absorbed in an elaborated form into the narrative of Welsh history. As a consequence, whilst Welsh history still sustains a version of Lloyd’s original thesis, the archaeological community is moving in the opposite direction. Present day archaeology regards the subjugation of Wales as having been completed by 78 A.D., with the conquest laying the foundations for a subsequent process of assimilation of the native population into Roman society. By the middle of the 2nd century A.D., that development provided the basis for a major demilitarisation of Wales. My aim in this article is to cast further light on the course of the Roman conquest of Wales and the subsequent process of assimilating the native population into Roman civil society. -

Aethelflaed: History and Legend

Quidditas Volume 34 Article 2 2013 Aethelflaed: History and Legend Kim Klimek Metropolitan State University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Klimek, Kim (2013) "Aethelflaed: History and Legend," Quidditas: Vol. 34 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol34/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quidditas 34 (2013) 11 Aethelflaed: History and Legend Kim Klimek Metropolitan State University of Denver This paper examines the place of Aethelflaed, Queen of the Mercians, in the written historical record. Looking at works like the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the Irish Annals, we find a woman whose rule acted as both a complement to and a corruption against the consolidations of Alfred the Great and Edward’s rule in Anglo-Saxon England. The alternative histories written by the Mercians and the Celtic areas of Ireland and Wales show us an alternative view to the colonization and solidification of West-Saxon rule. Introduction Aethelflaed, Queen and Lady of the Mercians, ruled the Anglo-Sax- on kingdom of Mercia from 911–918. Despite the deaths of both her husband and father and increasing Danish invasions into Anglo- Saxon territory, Aethelflaed not only held her territory but expanded it. She was a warrior queen whose Mercian army followed her west to fight the Welsh and north to attack the Danes.