Geoffrey of Monmouth and Medieval Welsh Historical Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(1913). Tome II

Notes du mont Royal www.notesdumontroyal.com 쐰 Cette œuvre est hébergée sur « No- tes du mont Royal » dans le cadre d’un exposé gratuit sur la littérature. SOURCE DES IMAGES Canadiana LES MABINOGION LES Mabinogion du Livre Rouge de HERGEST avec les variantes du Livre Blanc de RHYDDERCH Traduits du gallois avec une introduction, un commentaire explicatif et des notes critiques FA R J. LOTH PROFESSEUR Ali COLLÈGE DE FRANCE ÉDITION ENTIÈREMENT REVUE, CORRXGÉE ET AUGMENTÉE FONTEMOING ET Cie, ÉDITEURS PARIS4, RUE LE son, 4 1913 . x 294-? i3 G 02; f! LES MABINOGION OWEIN (1’ ET LUNET i2) ou la Dame de la Fontaine L’empereur Arthur se trouvait à Kaer Llion (3)sur W’ysc. Or un jour il était assis dans sa chambre en. (1) Owen ab Urycn est un des trois gingndqyrn (rois bénis) de l’île (Triades Mab., p. 300, 7). Son barde, Degynelw, est un des trois gwaewrudd ou hommes à la lance rouge (Ibid., p. 306, 8 ; d’autres triades appellent ce barde Tristvardd (Skene. Il, p. 458). Son cheval, Carnavlawc, est un des trois anreilhvarch ou che- vaux de butin (Livre Noir, Skene,ll, p. 10, 2). Sa tombe est à Llan Morvael (Ibid., p. 29, 25 ; cf. ibid, p. 26, 6 ; 49, 29, 23). Suivant Taliesin, Owein aurait tué Ida Flamddwyn ou Ida Porte-brandon, qui paraît être le roi de Northumbrie, dont la chronique anglo- saxonne fixe la mort à l’année 560(Petrie, Mon. hist. brit., Taliesin, Skene, Il, p. 199, XLIV). Son père, Uryen, est encore plus célè- bre. -

Gwydir Family

THE HISTORY OF THE GWYDIR FAMILY, WRITTEN BY SIR JOHN WYNNE, KNT. AND BART., UT CREDITUR, & PATET. OSWESTRY: \VOODJ\LL i\KD VENABLES, OS\VALD ROAD. 1878. WOODALL AND VENABLES, PRINTERS, BAILEY-HEAD AND OSWALD-ROAD. OSWESTRY. TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE CLEMENTINA ELIZABETH, {!N HER OWN lHGHT) BARONESS WILLOUGHBY DE ERESBY, THE REPRESENTATIVE OF 'l'HE OLD GWYDIR STOCK AND THE OWNER OF THE ESTATE; THE FOURTEENTH WHO HAS BORNE THAT ANCIENT BARONY: THIS EDITION OF THE HISTORY OF THE GWYDIR FAMILY IS, BY PERMISSION, RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY THE PUBLISHERS. OSWALD ROAD, OSWESTRY, 1878. PREFACE F all the works which have been written relating to the general or family history O of North Wales, none have been for centuries more esteemed than the History of the Gwydir Family. The Hon. Daines Barrington, in his preface to his first edition of the work, published in 1770, has well said, "The MS. hath, for above.a cent~ry, been so prized in North Wales, that many in those parts have thought it worth while to make fair and complete transcripts of it." Of these transcripts the earliest known to exist is one in the Library at Brogyntyn. It was probably written within 45 years of the death of the author; but besides that, it contains a great number of notes and additions of nearly the same date, which have never yet appeared in print. The History of the Gwydir Family has been thrice published. The first editiun, edited by the Hon. Daines Barrington, issued from the press in 1770. The second was published in Mr. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16336-2 — Medieval Historical Writing Edited by Jennifer Jahner , Emily Steiner , Elizabeth M

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16336-2 — Medieval Historical Writing Edited by Jennifer Jahner , Emily Steiner , Elizabeth M. Tyler Index More Information Index 1381 Rising. See Peasants’ Revolt Alcuin, 123, 159, 171 Alexander Minorita of Bremen, 66 Abbo of Fleury, 169 Alexander the Great (Alexander III), 123–4, Abbreviatio chronicarum (Matthew Paris), 230, 233 319, 324 Alfred of Beverley, Annales, 72, 73, 78 Abbreviationes chronicarum (Ralph de Alfred the Great, 105, 114, 151, 155, 159–60, 162–3, Diceto), 325 167, 171, 173, 174, 175, 176–7, 183, 190, 244, Abelard. See Peter Abelard 256, 307 Abingdon Apocalypse, 58 Allan, Alison, 98–9 Adam of Usk, 465, 467 Allen, Michael I., 56 Adam the Cellarer, 49 Alnwick, William, 205 Adomnán, Life of Columba, 301–2, 422 ‘Altitonantis’, 407–9 Ælfflæd, abbess of Whitby, 305 Ambrosius Aurelianus, 28, 33 Ælfric of Eynsham, 48, 152, 171, 180, 306, 423, Amis and Amiloun, 398 425, 426 Amphibalus, Saint, 325, 330 De oratione Moysi, 161 Amra Choluim Chille (Eulogy of St Lives of the Saints, 423 Columba), 287 Aelred of Rievaulx, 42–3, 47 An Dubhaltach Óg Mac Fhirbhisigh (Dudly De genealogia regum Anglorum, 325 Ferbisie or McCryushy), 291 Mirror of Charity, 42–3 anachronism, 418–19 Spiritual Friendship, 43 ancestral romances, 390, 391, 398 Aeneid (Virgil), 122 Andreas, 425 Æthelbald, 175, 178, 413 Andrew of Wyntoun, 230, 232, 237 Æthelred, 160, 163, 173, 182, 307, 311 Angevin England, 94, 390, 391, 392, 393 Æthelstan, 114, 148–9, 152, 162 Angles, 32, 103–4, 146, 304–5, 308, 315–16 Æthelthryth (Etheldrede), -

The Matter of Britain

THE MATTER OF BRITAIN: KING ARTHUR'S BATTLES I had rather myself be the historian of the Britons than nobody, although so many are to be found who might much more satisfactorily discharge the labour thus imposed on me; I humbly entreat my readers, whose ears I may offend by the inelegance of my words, that they will fulfil the wish of my seniors, and grant me the easy task of listening with candour to my history May, therefore, candour be shown where the inelegance of my words is insufficient, and may the truth of this history, which my rustic tongue has ventured, as a kind of plough, to trace out in furrows, lose none of its influence from that cause, in the ears of my hearers. For it is better to drink a wholesome draught of truth from a humble vessel, than poison mixed with honey from a golden goblet Nennius CONTENTS Chapter Introduction 1 The Kinship of the King 2 Arthur’s Battles 3 The River Glein 4 The River Dubglas 5 Bassas 6 Guinnion 7 Caledonian Wood 8 Loch Lomond 9 Portrush 10 Cwm Kerwyn 11 Caer Legion 12 Tribuit 13 Mount Agned 14 Mount Badon 15 Camlann Epilogue Appendices A Uther Pendragon B Arthwys, King of the Pennines C Arthur’s Pilgrimages D King Arthur’s Bones INTRODUCTION Cupbearer, fill these eager mead-horns, for I have a song to sing. Let us plunge helmet first into the Dark Ages, as the candle of Roman civilisation goes out over Europe, as an empire finally fell. The Britons, placid citizens after centuries of the Pax Romana, are suddenly assaulted on three sides; from the west the Irish, from the north the Picts & from across the North Sea the Anglo-Saxons. -

The Governing Body of the Church in Wales Corff Llywodraethol Yr Eglwys Yng Nghymru

For Information THE GOVERNING BODY OF THE CHURCH IN WALES CORFF LLYWODRAETHOL YR EGLWYS YNG NGHYMRU REPORT OF THE STANDING COMMITTEE TO THE GOVERNING BODY APRIL 2016 Members of the Governing Body may welcome brief background information on the individuals who are the subject of the recommendations in the Report and/or have been appointed by the Standing Committee to represent the Church in Wales. The Reverend Canon Joanna Penberthy (paragraph 4 and 28) Rector, Llandrindod and Cefnllys with Diserth with Llanyre and Llanfihangel Helygen. The Reverend Dr Ainsley Griffiths (paragraph 4) Chaplain, University of Wales Trinity Saint David, Camarthen Campus, CMD Officer, St Davids, member of the Standing Doctrinal Commission. (NB Dr Griffiths subsequently declined co-option and resigned his membership.) His Honour Judge Andrew Keyser QC (paragraph 4) Member of the Standing Committee, Judge in Cardiff, Deputy Chancellor of Llandaff Diocese, Chair of the Legal Sub-committee, former Deputy President of the Disciplinary Tribunal of the Church in Wales. Governing Body Assessor. Mr Mark Powell QC (paragraph 4 and 29) Chancellor of Monmouth diocese and Deputy President of the Disciplinary Tribunal. Deputy Chair of the Mental Health Tribunal for Wales. Chancellor of the diocese of Birmingham. Solicitor. Miss Sara Burgess (paragraph 4) Contributor to the life of the Parish of Llandaff Cathedral in particular to the Sunday School in which she is a leader. Mr James Tout (paragraph 4) Assistant Subject Director of Science, the Marches Academy, Oswestry. Worship Leader in the diocese of St Asaph for four years. Mrs Elizabeth Thomas (paragraph 5) Elected member of the Governing Body for the diocese of St Davids. -

The End of Celtic Britain and Ireland. Saxons, Scots and Norsemen

THE GREATNESS AND DECLINE OF THE CELTS CHAPTER III THE END OF CELTIC BRITAIN AND IRELAND. SAXONS, SCOTS, AND NORSEMEN I THE GERMANIC INVASIONS THE historians lay the blame of bringing the Saxons into Britain on Vortigern, [Lloyd, CCCCXXXVIII, 79. Cf. A. W. W. Evans, "Les Saxons dans l'Excidium Britanniæ", in LVI, 1916, p. 322. Cf. R.C., 1917 - 1919, p. 283; F.Lot, "Hangist, Horsa, Vortigern, et la conquête de la Gde.-Bretagne par les Saxons," in CLXXIX.] who is said to have called them in to help him against the Picts in 449. Once again we see the Celts playing the weak man’s game of putting yourself in the hands of one enemy to save yourself from another. According to the story, Vortigern married a daughter of Hengist and gave him the isle of Thanet and the Kentish coast in exchange, and the alliance between Vortigern and the Saxons came to an end when the latter treacherously massacred a number of Britons at a banquet. Vortigern fled to Wales, to the Ordovices, whose country was then called Venedotia (Gwynedd). They were ruled by a line of warlike princes who had their capita1 at Aberffraw in Anglesey. These kings of Gwynedd, trained by uninterrupted fighting against the Irish and the Picts, seem to have taken on the work of the Dukes of the Britains after Ambrosius or Arthur, and to have been regarded as kings in Britain as a whole. [Lloyd, op. cit., p. 102.] It was apparently at this time that the name of Cymry, which became the national name of the Britons, came to prevail. -

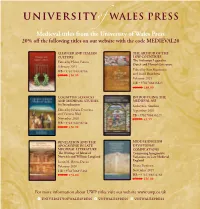

Medieval Titles from the University of Wales Press 20% Off the Following Titles on Our Website with the Code MEDIEVAL20

Medieval titles from the University of Wales Press 20% off the following titles on our website with the code MEDIEVAL20 CHAUCER AND ITALIAN THE ARTHUR OF THE CULTURE LOW COUNTRIES The Arthurian Legend in Edited by Helen Fulton Dutch and Flemish Literature February 2021 HB • 9781786836786 Edited by Bart Besamusca £70.00 £56.00 and Frank Brandsma February 2021 HB • 9781786836823 £80.00 £64.00 COGNITIVE SCIENCES INTRODUCING THE AND MEDIEVAL STUDIES MEDIEVAL ASS An Introduction Kathryn L. Smithies Edited by Juliana Dresvina September 2020 and Victoria Blud PB • 9781786836229 November 2020 £11.99 £9.59 HB • 9781786836748 £70.00 £56.00 REVELATION AND THE MIDDLE ENGLISH APOCALYPSE IN LATE DEVOTIONAL MEDIEVAL LITERATURE COMPILATIONS The Writings of Julian of Composing Imaginative Norwich and William Langland Variations in Late Medieval Justin M. Byron-Davies England February 2020 Diana Denissen HB • 9781786835161 November 2019 £70.00 £56.00 HB • 9781786834768 £70.00 £56.00 For more information about UWP titles visit our website www.uwp.co.uk B UNIVERSITYOFWALESPRESS A UNIWALESPRESS V UNIWALESPRESS 20% OFF WITH THE CODE MEDIEVAL20 TRIOEDD YNYS PRYDEIN GEOFFREY OF MONMOUTH PRINCESSES OF WALES The Triads of the Island of Britain Karen Jankulak Deborah Fisher THE ECONOMY OF MEDIEVAL Edited by Rachel Bromwich PB • 9780708321515 £7.99 £4.00 PB • 9780708319369 £3.99 £2.00 WALES, 1067-1536 PB • 9781783163052 £24.99 £17.49 Matthew Frank Stevens GENDERING THE CRUSADES REVISITING THE MEDIEVAL PB • 9781786834843 £24.99 £19.99 THE WELSH AND Edited by Susan B. Edgington NORTH OF ENGLAND THE MEDIEVAL WORLD and Sarah Lambert Interdisciplinary Approaches INTRODUCING THE MEDIEVAL Travel, Migration and Exile PB • 9780708316986 £19.99 £10.00 Edited by Anita Auer, Denis Renevey, DRAGON Edited by Patricia Skinner Camille Marshall and Tino Oudesluijs Thomas Honegger HOLINESS AND MASCULINITY PB • 9781786831897 £29.99 £20.99 PB • 9781786833945 £35.00 £17.50 PB • 9781786834683 £11.99 £9.59 IN THE MIDDLE AGES 50% OFF WITH THE CODE MEDIEVAL50 Edited by P. -

The Emergence of the Cumbrian Kingdom

The emergence and transformation of medieval Cumbria The Cumbrian kingdom is one of the more shadowy polities of early medieval northern Britain.1 Our understanding of the kingdom’s history is hampered by the patchiness of the source material, and the few texts that shed light on the region have proved difficult to interpret. A particular point of debate is the interpretation of the terms ‘Strathclyde’ and ‘Cumbria’, a matter that has periodically drawn comment since the 1960s. Some scholars propose that the terms were applied interchangeably to the same polity, which stretched from Clydesdale to the Lake District. Others argue that the terms applied to different territories: Strathclyde was focused on the Clyde Valley whereas Cumbria/Cumberland was located to the south of the Solway. The debate has significant implications for our understanding of the extent of the kingdom(s) of Strathclyde/Cumbria, which in turn affects our understanding of politics across tenth- and eleventh-century northern Britain. It is therefore worth revisiting the matter in this article, and I shall put forward an interpretation that escapes from the dichotomy that has influenced earlier scholarship. I shall argue that the polities known as ‘Strathclyde’ and ‘Cumbria’ were connected but not entirely synonymous: one evolved into the other. In my view, this terminological development was prompted by the expansion of the kingdom of Strathclyde beyond Clydesdale. This reassessment is timely because scholars have recently been considering the evolution of Cumbrian identity across a much longer time-period. In 1974 the counties of Cumberland and Westmorland were joined to Lancashire-North-of the-Sands and part of the West Riding of Yorkshire to create the larger county of Cumbria. -

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook Discover the legends of the mighty princes of Gwynedd in the awe-inspiring landscape of North Wales PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK Front Cover: Criccieth Castle2 © Princes of Gwynedd 2013 of © Princes © Cadw, Welsh Government (Crown Copyright) This page: Dolwyddelan Castle © Conwy County Borough Council PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 3 Dolwyddelan Castle Inside this book Step into the dramatic, historic landscapes of Wales and discover the story of the princes of Gwynedd, Wales’ most successful medieval dynasty. These remarkable leaders were formidable warriors, shrewd politicians and generous patrons of literature and architecture. Their lives and times, spanning over 900 years, have shaped the country that we know today and left an enduring mark on the modern landscape. This guidebook will show you where to find striking castles, lost palaces and peaceful churches from the age of the princes. www.snowdoniaheritage.info/princes 4 THE PRINCES OF GWYNEDD TOUR © Sarah McCarthy © Sarah Castell y Bere The princes of Gwynedd, at a glance Here are some of our top recommendations: PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 5 Why not start your journey at the ruins of Deganwy Castle? It is poised on the twin rocky hilltops overlooking the mouth of the River Conwy, where the powerful 6th-century ruler of Gwynedd, Maelgwn ‘the Tall’, once held court. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If it’s a photo opportunity you’re after, then Criccieth Castle, a much contested fortress located high on a headland above Tremadog Bay, is a must. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If you prefer a remote, more contemplative landscape, make your way to Cymer Abbey, the Cistercian monastery where monks bred fine horses for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, known as Llywelyn ‘the Great’. -

Graham Dzons.Indd

Ni{ i Vizantija V 513 Graham Jones PROCLAIMED AT YORK: THE IMPACT OF CONSTANTINE, SAINT AND EMPEROR, ON COLLECTIVE BRITISH MEMORIES Constantine, raised to Augustan rank by the acclaim of the Roman sol- diers at York in 306, was not the only emperor whose reign began in Britain. As one of Rome’s most distant territories, and of course an island (Fig. 1), Britain seems always to have been vunerable to revolt, as indeed were all the west- ernmost provinces to greater or lesser degree.1 As early as 197, Albinus seized power in the West. Two generations later came the so-called Gallic Empire of Gallienus and his successors, in which Britain was involved together with Gaul, Spain and the Low Countries. It lasted for about twenty years in the middle of the third century. A series of usurpers – most famously Magnus Maximus, proclaimed emperor in Britain in 383, but continuing with Marcus in 406/7, Gratian in the latter year, and Constantine III from 408 to 411 – led the British monk Gildas, writing around 500, to describe his country as a ‘thicket of ty- rants’, echoing Jerome’s phrase that Britain was ‘fertile in usurpers’. Indeed, Constantine’s proclamation might not have happened at York were it not for the involvement of his father in pacifying Britain. Constantius crossed to Britain in 296 to end a ten-year revolt by a Belgian commander Carausius and his succes- sor Allectus. Constantius’ action in preventing the sack of London by part of the defeated army was commemorated by a famous gold medallion on which he is shown receiving the thanks of the city’s inhabitants as Redditor Lucis Aeternam (Fig. -

The Search for San Ffraid

The Search for San Ffraid ‘A thesis submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in the fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts’ 2012 Jeanne Mehan 1 Abstract The Welsh traditions related to San Ffraid, called in Ireland and Scotland St Brigid (also called Bride, Ffraid, Bhríde, Bridget, and Birgitta) have not previously been documented. This Irish saint is said to have traveled to Wales, but the Welsh evidence comprises a single fifteenth-century Welsh poem by Iorwerth Fynglwyd; numerous geographical dedications, including nearly two dozen churches; and references in the arts, literature, and histories. This dissertation for the first time gathers together in one place the Welsh traditions related to San Ffraid, integrating the separate pieces to reveal a more focused image of a saint of obvious importance in Wales. As part of this discussion, the dissertation addresses questions about the relationship, if any, of San Ffraid, St Brigid of Kildare, and St Birgitta of Sweden; the likelihood of one San Ffraid in the south and another in the north; and the inclusion of the goddess Brigid in the portrait of San Ffraid. 2 Contents ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ 2 CONTENTS........................................................................................................................ 3 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................... -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’).