National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Pre-Boom Developers of Dade County : Tequesta

Some Pre-Boom Developers of Dade County By ADAM G. ADAMS The great land boom in Florida was centered in 1925. Since that time much has been written about the more colorful participants in developments leading to the climax. John S. Collins, the Lummus brothers and Carl Fisher at Miami Beach and George E. Merrick at Coral Gables, have had much well deserved attention. Many others whose names were household words before and during the boom are now all but forgotten. This is an effort, necessarily limited, to give a brief description of the times and to recall the names of a few of those less prominent, withal important develop- ers of Dade County. It seems strange now that South Florida was so long in being discovered. The great migration westward which went on for most of the 19th Century in the United States had done little to change the Southeast. The cities along the coast, Charleston, Savannah, Jacksonville, Pensacola, Mobile and New Orleans were very old communities. They had been settled for a hundred years or more. These old communities were still struggling to overcome the domination of an economy controlled by the North. By the turn of the century Progressives were beginning to be heard, those who were rebelling against the alleged strangle hold the Corporations had on the People. This struggle was vehement in Florida, including Dade County. Florida had almost been forgotten since the Seminole Wars. There were no roads penetrating the 350 miles to Miami. All traffic was through Jacksonville, by rail or water. There resided the big merchants, the promi- nent lawyers and the ruling politicians. -

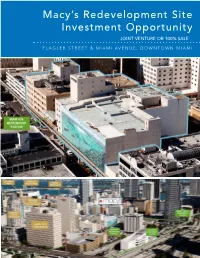

Macy's Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity

Macy’s Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity JOINT VENTURE OR 100% SALE FLAGLER STREET & MIAMI AVENUE, DOWNTOWN MIAMI CLAUDE PEPPER FEDERAL BUILDING TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 13 CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT OVERVIEW 24 MARKET OVERVIEW 42 ZONING AND DEVELOPMENT 57 DEVELOPMENT SCENARIO 64 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 68 LEASE ABSTRACT 71 FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: PRIMARY CONTACT: ADDITIONAL CONTACT: JOHN F. BELL MARIANO PEREZ Managing Director Senior Associate [email protected] [email protected] Direct: 305.808.7820 Direct: 305.808.7314 Cell: 305.798.7438 Cell: 305.542.2700 100 SE 2ND STREET, SUITE 3100 MIAMI, FLORIDA 33131 305.961.2223 www.transwestern.com/miami NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITION, WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY LISTING CONDITIONS, IMPOSED BY THE OWNER. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MACY’S SITE MIAMI, FLORIDA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Downtown Miami CBD Redevelopment Opportunity - JV or 100% Sale Residential/Office/Hotel /Retail Development Allowed POTENTIAL FOR UNIT SALES IN EXCESS OF $985 MILLION The Macy’s Site represents 1.79 acres of prime development MACY’S PROJECT land situated on two parcels located at the Main and Main Price Unpriced center of Downtown Miami, the intersection of Flagler Street 22 E. Flagler St. 332,920 SF and Miami Avenue. Macy’s currently has a store on the site, Size encompassing 522,965 square feet of commercial space at 8 W. Flagler St. 189,945 SF 8 West Flagler Street (“West Building”) and 22 East Flagler Total Project 522,865 SF Street (“Store Building”) that are collectively referred to as the 22 E. -

Redland Tropical Trail Brochure

Spend a Night on the Trail & More. ESCAPE the traffic and noise of the city and EXPLORE the agri-tourism south Miami-Dade offers. Come ENJOY Miami-Dade’s countryside. 1 Value Place Lodging Homestead’s Popular Extended Stay Lodging 2750 NE 8th St., Homestead 33033 305 245 5000 • 1 877 497 5223 • TPKE Exit 2 • TPKE exit 2 Corner of Campbell Dr. (SW 312 St.) & Kingman Rd (152nd Ave.) Because our studios are very comfortable, secure and affordable, Value Place encourages you and your visiting family members to extend your stay a week or more with us and visit every site in this brochure, while enjoying Nestled between the unique treasures of the natural wonders of South Florida. Youʼll appreciate how we value our Everglades National Park and Biscayne guests, and how our community treasures your visit! National Park lies an area rich in history, beauty, tropical climate and tempting food. 2 Shiver’s Bar-B-Q 28001 S. Dixie Hwy Discover acres of incredible tropical fruits and Homestead, Fl 33033 vegetables, stunning orchids and beautiful (305) 248-9475 • www.shiversbbq.com One of South Floridaʼs best kept secrets. bonsai trees.Taste exotic fruit wines, luscious Serving authentic hickory smoked BBQ for over 60 years! Family owned homemade milkshakes, fabulous Italian and and operated, Shiverʼs offers smoked pulled pork, beef brisket, baby back ribs, beef ribs, and more. Come enjoy some great BBQ and local cuisine. Encounter wild alligators and Southern hospitality at Shiverʼs Bar-B-Q! uncaged monkeys, explore a love story in stone, shop and dine in a lush tropical garden with 3 The Little Farm fountains and sculptures, and catch an exciting Gentle farm animals for enjoyment and education airboat ride into the Florida Everglades. -

Miami-Dade County Commission on Ethics and Public Trust

Biscayne Building 19 West Flagler Street Miami-Dade County Suite 220 Miami, Florida 33130 Commission on Ethics Phone: (305) 579-2594 Fax: (305) 579-2656 and Public Trust Memo To: Mike Murawski, independent ethics advocate Cc: Manny Diaz, ethics investigator From: Karl Ross, ethics investigator Date: Nov. 14, 2007 Re: K07-097, ABDA/ Allapattah Construction Inc. Investigative findings: Following the June 11, 2007, release of Audit No. 07-009 by the city of Miami’s Office of Independent Auditor General, COE reviewed the report for potential violations of the Miami-Dade ethics ordinance. This review prompted the opening of two ethics cases – one leading to a complaint against Mr. Sergio Rok for an apparent voting conflict – and the second ethics case captioned above involving Allapattah Construction Inc., a for-profit subsidiary of the Allapattah Business Development Authority. At issue is whether executives at ABDA including now Miami City Commissioner Angel Gonzalez improperly awarded a contract to Allapattah Construction in connection with federal affordable housing grants awarded through the city’s housing arm, the Department of Community Development. ABDA is a not-for-profit social services agency, and appeared to pay itself as much as $196,000 in profit and overhead in connection with the Ralph Plaza I and II projects, according to documents obtained from the auditor general. The city first awarded federal Home Investment Partnership Program (HOME) funds to ABDA on April 15, 1998, in the amount of $500,000 in connection with Ralph Plaza phase II. On Dec. 17, 2002, the city again awarded federal grant monies to ABDA in the amount of $730,000 in HOME funds for Ralph Plaza phase II. -

Front Desk Concierge Book Table of Contents

FRONT DESK CONCIERGE BOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS I II III HISTORY MUSEUMS DESTINATION 1.1 Miami Beach 2.1 Bass Museum of Art ENTERTAINMENT 1.2 Founding Fathers 2.2 The Wolfsonian 3.1 Miami Metro Zoo 1.3 The Leslie Hotels 2.3 World Erotic Art Museum (WEAM) 3.2 Miami Children’s Museum 1.4 The Nassau Suite Hotel 2.4 Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) 3.3 Jungle Island 1.5 The Shepley Hotel 2.5 Miami Science Museum 3.4 Rapids Water Park 2.6 Vizcaya Museum & Gardens 3.5 Miami Sea Aquarium 2.7 Frost Art Museum 3.6 Lion Country Safari 2.8 Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) 3.7 Seminole Tribe of Florida 2.9 Lowe Art Museum 3.8 Monkey Jungle 2.10 Flagler Museum 3.9 Venetian Pool 3.10 Everglades Alligator Farm TABLE OF CONTENTS IV V VI VII VIII IX SHOPPING MALLS MOVIE THEATERS PERFORMING CASINO & GAMING SPORTS ACTIVITIES SPORTING EVENTS 4.1 The Shops at Fifth & Alton 5.1 Regal South Beach VENUES 7.1 Magic City Casino 8.1 Tennis 4.2 Lincoln Road Mall 5.2 Miami Beach Cinematheque (Indep.) 7.2 Seminole Hard Rock Casino 8.2 Lap/Swimming Pool 6.1 New World Symphony 9.1 Sunlife Stadium 5.3 O Cinema Miami Beach (Indep.) 7.3 Gulfstream Park Casino 8.3 Basketball 4.3 Bal Harbour Shops 9.2 American Airlines Arena 6.2 The Fillmore Miami Beach 7.4 Hialeah Park Race Track 8.4 Golf 9.3 Marlins Park 6.3 Adrienne Arscht Center 8.5 Biking 9.4 Ice Hockey 6.4 American Airlines Arena 8.6 Rowing 9.5 Crandon Park Tennis Center 6.5 Gusman Center 8.7 Sailing 6.6 Broward Center 8.8 Kayaking 6.7 Hard Rock Live 8.9 Paddleboarding 6.8 BB&T Center 8.10 Snorkeling 8.11 Scuba Diving 8.12 -

SEOPW Redevelopment Plan

NOVEMBER 2004 by Dover Kohl & Partners FINAL UPDATE MAY 2009 by the City of Miami Planning Department (Ver. 2.0) i Table of Contents for the Southeast Overtown/Park West Community Redevelopment Plan November 2004 Final Updated May 2009 Section ONE Introduction Page 2 • This Document 2 • Topics Frequently Asked from Neighborhood Stakeholders 2 • Historical Context Page 3 • 21st Century Context Page 5 • The Potential: A Livable City 5 • History of the CRA Page 6 • Revised Boundaries 6 • Revisions from the Original CRA Redevelopment Plan Page 7 • Findings of Necessity Page 9 • New Legal Description Section TWO Goals and Guiding Principles Page 11 • Redevelopment Goals #1 Preserving Historic Buildings & Community Heritage #2 Expanding the Tax Base using Smart Growth Principles #3 Housing: Infill, Diversity, & Retaining Affordability #4 Creating Jobs within the Community #5 Promotion & Marketing of the Community #6 Improving the Quality of Life for Residents Page 13 • Guiding Principles 1. The community as a whole has to be livable. Land uses and transportation systems must be coordinated with each other. 2. The neighborhood has to retain access to affordable housing even as the neighborhood becomes more desirable to households with greater means. 3. There must be variety in housing options. ii 4. There must be variety in job options. 5. Walking within the neighborhood must be accessible, safe, and pleasant. 6. Local cultural events, institutions, and businesses are to be promoted. Section TWO 7. The City and County must provide access to small parks and green spaces of an urban (continued) character. 8. Older buildings that embody the area’s cultural past should be restored. -

Vendor List for Campaign Contributions

VENDOR LIST FOR CAMPAIGN CONTRIBUTIONS Vendor # Vendor Name Address 1 Address 2 City State Contact Name Phone Email 371 3000 GRATIGNY ASSOCIATES LLC 100 FRONT STREET SUITE 350 CONSHOHOCKEN PA J GARCIA [email protected] 651 A & A DRAINAGE & VAC SERVICES INC 5040 KING ARTHUR AVENUE DAVIE FL 954 680 0294 [email protected] 1622 A & B PIPE & SUPPLY INC 6500 N.W. 37 AVENUE MIAMI FL 305-691-5000 [email protected] 49151 A & J ROOFING CORP 4337 E 11 AVENUE HIALEAH FL MIGUEL GUERRERO 305.599.2782 [email protected] 1537 A NATIONAL SALUTE TO AMERICA'S HEROES LLC 10394 W SAMPLE ROAD SUITE 200 POMPANO BEACH FL MICKEY 305 673 7577 6617 [email protected] 50314 A NATIVE TREE SERVICE, INC. 15733 SW 117 AVENUE MIAMI FL CATHY EVENSEN [email protected] 7928 AAA AUTOMATED DOOR REPAIR INC 21211 NE 25 CT MIAMI FL 305-933-2627 [email protected] 10295 AAA FLAG AND BANNER MFG CO INC 681 NW 108TH ST MIAMI FL [email protected] 43804 ABC RESTAURANT SUPPLY & EQUIPM 1345 N MIAMI AVENUE MIAMI FL LEONARD SCHUPAK 305-325-1200 [email protected] 35204 ABC TRANSFER INC. 307 E. AZTEC AVENUE CLEWISTON FL 863-983-1611 X 112 [email protected] 478 ACADEMY BUS LLC 3595 NW 110 STREET MIAMI FL V RUIZ 305-688-7700 [email protected] 980 ACAI ASSOCIATES, INC. 2937 W. CYPRESS CREEK ROAD SUITE 200 FORT LAUDERDALE FL 954-484-4000 [email protected] 14534 ACCELA INC 2633 CAMINO RAMON SUITE 500 SAN RAMON CA 925-659-3275 [email protected] 49840 ACME BARRICADES LC 9800 NORMANDY BLVD JACKSONVILLE FL STEPHANIE RABBEN (904) 781-1950 X122 [email protected] 1321 ACORDIS INTERNATIONAL CORP 11650 INTERCHANGE CIRCLE MIRAMAR FL JAY SHUMHEY [email protected] 290 ACR, LLC 184 TOLLGATE BRANCH LONGWOOD FL 407-831-7447 [email protected] 53235 ACTECH COPORATION 14600 NW 112 AVENUE HIALEAH FL 16708 ACUSHNET COMPANY TITLEIST P.O. -

1200 Brickell Avenue, Miami, Florida 33131

Jonathan C. Lay, CCIM MSIRE MSF T 305 668 0620 www.FairchildPartners.com 1200 Brickell Avenue, Miami, Florida 33131 Senior Advisor | Commercial Real Estate Specialist [email protected] Licensed Real Estate Brokers AVAILABLE FOR SALE VIA TEN-X INCOME PRODUCING OFFICE CONDOMINIUM PORTFOLIO 1200 Brickell is located in the heart of Miami’s Financial District, and offers a unique opportunity to invest in prime commercial real estate in a gloabl city. Situated in the corner of Brickell Avenue and Coral Way, just blocks from Brickell City Centre, this $1.05 billion mixed-used development heightens the area’s level of urban living and sophistication. PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS DESCRIPTION • Common areas undergoing LED lighting retrofits LOCATION HIGHLIGHTS • 20- story, ± 231,501 SF • Upgraded fire panel • Located in Miami’s Financial District • Typical floor measures 11,730 SF • Direct access to I-95 • Parking ratio 2/1000 in adjacent parking garage AMENITIES • Within close proximity to Port Miami, American • Porte-cochere off of Brickell Avenue • Full service bank with ATM Airlines Arena, Downtown and South Beach • High-end finishes throughout the building • Morton’s Steakhouse • Closed proximity to Metromover station. • Lobby cafeteria BUILDING UPGRADES • 24/7 manned security & surveillance cameras • Renovated lobby and common areas • Remote access • New directory • On-site manager & building engineer • Upgraded elevator • Drop off lane on Brickell Avenue • Two new HVAC chillers SUITES #400 / #450 FLOOR PLAN SUITE SIZE (SF) OCCUPANCY 400 6,388 Vacant 425 2,432 Leased Month to Month 450 2,925 Leased Total 11,745 Brickell, one of Miami’s fastest-growing submarkets, ranks amongst the largest financial districts in the United States. -

Section 2.1: Architectural Styles

SECTION 2.1: ARCHITECTURAL STYLES BRIEF HISTORY OF THE CITY OF MIAMI Before the first European settlers set foot in South Florida; the Tequesta people inhabited this land. The Tequesta’s alongside other natives reached the astonishing number of 100,000 in population. Together they developed a complex society of living in communities that were planned and executed by early construction projects. The Tequesta people left behind a heritage in archaeological resources including the Miami Circle, Miami River Rapids, and the North Bank of the Miami River which all add greatly to the remarkable cultural patrimony of Miami. The first permanent European settlers arrived to South Florida in the early 19th century. Two families with Bahamian roots, received land grants from the Spanish Government when they owned Florida. These settlers were joined by Bahamian immigrants looking for employment, the Seminole Indians, and runaway slaves. They ferociously disputed the non-native absorption of Seminole lands in three Seminole Wars (1817-1818, 1835-1842, and 1855-1858). Few United States soldiers stayed after the end of the third and last Seminole War. It wasn’t until 1846 when South Florida was first surveyed the area flourished once the United States implemented the “Homestead Act” in 1862 which granted 160 acres of land to men willing to live on the land for at least five years. Important early residents included William Brickell and Julia Tuttle who brought the early Spanish grants. Together they convinced Henry Flagler to expand his rail line south to Miami. With the railroad, progress came to Miami and the first building boom occurred in 1900s to 1930s. -

Jim Crow at the Beach: an Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Biscayne National Park Jim Crow at the Beach: An Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park. ON THE COVER Biscayne National Park’s Visitor Center harbor, former site of the “Black Beach” at the once-segregated Homestead Bayfront Park. Photo by Biscayne National Park Jim Crow at the Beach: An Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park. BISC Acc. 413. Iyshia Lowman, University of South Florida National Park Service Biscayne National Park 9700 SW 328th St. Homestead, FL 33033 December, 2012 U.S. Department of the InteriorNational Park Service Biscayne National Park Homestead, FL Contents Figures............................................................................................................................................ iii Acknowledgments.......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 A Period in Time ............................................................................................................................. 1 The Long Road to Segregation ....................................................................................................... 4 At the Swimming Hole .................................................................................................................. -

Southern District of Florida Certified Mediator List Adelso

United States District Court - Southern District of Florida Certified Mediator List Current as of: Friday, March 12, 2021 Mediator: Adelson, Lori Firm: HR Law PRO/Adelson Law & Mediation Address: 401 East Las Olas Blvd. Suite 1400 Fort Lauderdale, FL 33301 Phone: 954-302-8960 Email: [email protected] Website: www.HRlawPRO.com Specialty: Employment/Labor Discrimination, Title Vll, FCRA Civil Rights, ADA, Title III, FMLA, Whistleblower, Non-compete, business disputes Locations Served: Broward, Indian River, Martin, Miami, Monroe, Palm Beach, St. Lucie Mediator: Alexander, Bruce G. Firm: Ciklin Lubitz Address: 515 N. Flagler Drive, 20th Floor West Palm Beach, FL 33401 Phone: 561-820-0332 Fax: 561-833-4209 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ciklinlubitz.com Languages: French Specialty: Construction Locations Served: Broward, Highlands, Indian River, Martin, Miami, Monroe, Okeechobee, Palm Beach, St. Lucie Mediator: Arrizabalaga, Markel Firm: K&A Mediation/Kleinman & Arrizabalaga, PA Address: 169 E. Flagler Street #1420 Miami, FL 33131 Phone: 305-377-2728 Fax: 305-377-8390 Email: [email protected] Website: www.kamediation.com Languages: Spanish Specialty: Personal Injury, Insurance, Commercial, Property Insurance, Medical Malpractice, Products Liability Locations Served: Broward, Miami, Palm Beach Page 1 of 24 Mediator: Barkett, John M. Firm: Shook Hardy & Bacon LLP Address: 201 S. Biscayne Boulevard Suite 2400 Miami, FL 33131 Phone: 305-358-5171 Fax: 305-358-7470 Email: [email protected] Specialty: Commercial, Environmental, -

95 Express Route 106 Weekdays

Reading a Timetable - It’s Easy 1. The map shows the exact bus route. Broward County Transit 2. Major route intersections are called time points. Time points are shown with the symbol . 3. The timetable lists major time points for bus route. 95 EXPRESS Listed under time points are scheduled departure times. 4. Reading from left to right, indicates the time for ROUTE 106 each bus trip. MIRAMAR 5. Arrive at the bus stop five minutes early. Buses operate as close to published timetables as traffic WEEKDAY SCHEDULE conditions allow. Miramar Regional Park to Civic Center/ Health District and Culmer Metrorail Station Information: 954-357-8400 Effective 8/8/21 Hearing-speech impaired/TTY: 954-357-8302 This publication can be made available in alternative formats upon request by contacting 954-357-8400 or TTY 954-357-8302. This symbol is used on bus stop signs to indicate accessible bus stops. New Schedule Monday – Friday • Face Covering Required • Maintain Social Distancing Real Time Bus Information MyRide.Broward.org BROWARD COUNTY BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS An equal opportunity employer and provider of services. 3,500 copies of this public document were promulgated at a gross cost of Broward.org/BCT $604, or $.173 per copy, to inform the public about the Transit Division’s schedule and route information. Printed 8/21 954-357-8400 SOUTHBOUND • Miramar Park & Ride NORTHBOUND • Culmer Metrorail to Culmer Metrorail Station Station to Miramar Park & Ride CULMER METRORAIL STATION 14 STREET & 12 AVENUE MIRAMAR PKWY & FLAMINGO RD MIRAMAR PARK &