Jack Snyder and Leslie Vinjamuri Source: International Security, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Power Seeking and Backlash Against Female Politicians

Article Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin The Price of Power: Power Seeking and 36(7) 923 –936 © 2010 by the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc Backlash Against Female Politicians Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0146167210371949 http://pspb.sagepub.com Tyler G. Okimoto1 and Victoria L. Brescoll1 Abstract Two experimental studies examined the effect of power-seeking intentions on backlash toward women in political office. It was hypothesized that a female politician’s career progress may be hindered by the belief that she seeks power, as this desire may violate prescribed communal expectations for women and thereby elicit interpersonal penalties. Results suggested that voting preferences for female candidates were negatively influenced by her power-seeking intentions (actual or perceived) but that preferences for male candidates were unaffected by power-seeking intentions. These differential reactions were partly explained by the perceived lack of communality implied by women’s power-seeking intentions, resulting in lower perceived competence and feelings of moral outrage. The presence of moral-emotional reactions suggests that backlash arises from the violation of communal prescriptions rather than normative deviations more generally. These findings illuminate one potential source of gender bias in politics. Keywords gender stereotypes, backlash, power, politics, intention, moral outrage Received June 5, 2009; revision accepted December 2, 2009 Many voters see Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton as coldly politicians and that these penalties may be reflected in voting ambitious, a perception that could ultimately doom her presi- preferences. dential campaign. Peter Nicholas, Los Angeles Times, 2007 Power-Relevant Stereotypes Power seeking may be incongruent with traditional female In 1916, Jeannette Rankin was elected to the Montana seat in gender stereotypes but not male gender stereotypes for a the U.S. -

The Leftist Case for War in Iraq •fi William Shawcross, Allies

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 27, Issue 6 2003 Article 6 Vengeance And Empire: The Leftist Case for War in Iraq – William Shawcross, Allies: The U.S., Britain, Europe, and the War in Iraq Hal Blanchard∗ ∗ Copyright c 2003 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Vengeance And Empire: The Leftist Case for War in Iraq – William Shawcross, Allies: The U.S., Britain, Europe, and the War in Iraq Hal Blanchard Abstract Shawcross is superbly equipped to assess the impact of rogue States and terrorist organizations on global security. He is also well placed to comment on the risks of preemptive invasion for existing alliances and the future prospects for the international rule of law. An analysis of the ways in which the international community has “confronted evil,” Shawcross’ brief polemic argues that U.S. President George Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair were right to go to war without UN clearance, and that the hypocrisy of Jacques Chirac was largely responsible for the collapse of international consensus over the war. His curious identification with Bush and his neoconservative allies as the most qualified to implement this humanitarian agenda, however, fails to recognize essential differences between the leftist case for war and the hard-line justification for regime change in Iraq. BOOK REVIEW VENGEANCE AND EMPIRE: THE LEFTIST CASE FOR WAR IN IRAQ WILLIAM SHAWCROSS, ALLIES: THE U.S., BRITAIN, EUROPE, AND THE WAR IN IRAQ* Hal Blanchard** INTRODUCTION In early 2002, as the war in Afghanistan came to an end and a new interim government took power in Kabul,1 Vice President Richard Cheney was discussing with President George W. -

Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2

Ilia State University Faculty of Arts and Sciences MA Level Course Syllabus 1. Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2. Spring Term COURSE DURATION 3. 6.0 ECTS 4. DISTRIBUTION OF HOURS Contact Hours • Lectures – 14 hours • Seminars – 12 hours • Midterm Exam – 2 hours • Final Exam – 2 hours • Research Project Presentation – 2 hours Independent Work - 118 hours Total – 150 hours 5. Nino Pavlenishvili INSTRUCTOR Associate Professor, PhD Ilia State University Mobile: 555 17 19 03 E-mail: [email protected] 6. None PREREQUISITES 7. Interactive lectures, topic-specific seminars with INSTRUCTION METHODS deliberations, debates, and group discussions; and individual presentation of the analytical memos, and project presentation (research paper and PowerPoint slideshow) 8. Within the course the students are to be introduced to COURSE OBJECTIVES the vast bulge of the literature on the causes of war and condition of peace. We pay primary attention to the theory and empirical research in the political science and international relations. We study the leading 1 theories, key concepts, causal variables and the processes instigating war or leading to peace; investigate the circumstances under which the outcomes differ or are very much alike. The major focus of the course is o the theories of interstate war, though it is designed to undertake an overview of the literature on civil war, insurgency, terrorism, and various types of communal violence and conflict cycles. We also give considerable attention to the methodology (qualitative/quantitative; small-N/large-N, Case Study, etc.) utilized in the well- known works of the leading scholars of the field and methodological questions pertaining to epistemology and research design. -

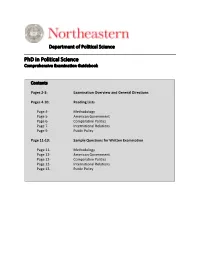

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

PRESCRIPTION DRUG COUPON STUDY Report to the Massachusetts Legislature JULY 2020

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS HEALTH POLICY COMMISSION PRESCRIPTION DRUG COUPON STUDY Report to the Massachusetts Legislature JULY 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In this report, required by Chapter 363 of the 2018 Session Prescription drug coupons are currently allowed in all 50 Laws, the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission (HPC) states for commercially-insured patients. Federal health examines the use and impact of prescription drug coupons insurance programs, such as Medicare, Medicaid, Tricare in Massachusetts. This report focuses on coupons issued by and Veteran’s Administration, prohibit the use of coupons pharmaceutical manufacturers that reduce a commercial based on federal anti-kickback statutes. Massachusetts patient’s cost-sharing. Prescription drug coupons are offered became the last state to authorize commercial coupon use almost exclusively on branded drugs, which comprise only in 2012 but continues to prohibit manufacturers from 10% of all prescriptions dispensed in the U.S., but account offering coupons and discounts on any prescription drug for 79% of total drug spending. Despite the immediate ben- that has an “AB rated” generic equivalent as determined efit of drug coupons to patients, policymakers and experts by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The 2012 debate whether and how coupons should be allowed in the law authorizing coupons in Massachusetts also contained commercial market given the potential relationship between a sunset provision, under which the law would have been coupon usage and increased spending on branded drugs repealed on July 1, 2015. However, this date of repeal versus lower cost alternatives. was postponed several times and ultimately extended to January 1, 2021. Massachusetts has long sought to con- Coupons reduce or eliminate the patient’s cost-sharing sider the impact of drug coupons on the Commonwealth’s responsibility required by the patient’s insurance plan, while landmark cost containment goals, as well as the benefits for the plan’s costs for the drug remain unchanged. -

'Go and Sin No More': Christian Mercy Vs. Tabloid Vengeance Stuart Dew Describes Some Biblical Examples of Forgiveness Towards Wrongdoers

'Go and Sin No More': Christian mercy vs. tabloid vengeance Stuart Dew describes some biblical examples of forgiveness towards wrongdoers. s I often do when talking in public on behalf and other high profile offenders as evil is comforting, of the Churches' Criminal Justice Forum for, if they are the personification of evil, the rest of A (CCJF), I asked the group of local us are okay. We are normal; we are the good guys. To churchgoers what Christian values they linked with consider that we are all capable of doing both right criminal justice. The first respondent folded his arms and wrong requires us to share ownership for dealing across his chest and said firmly "Punishment for sin". with criminal behaviour. That is a message that It wasn't one of the values at the forefront of my Churches' Criminal Justice Forum tries to put across. mind, and I wondered if this might be a more One of my favourite Bible stories is where a group challenging evening than some. However, it proved of men bring to Christ a woman caught in adultery. to be a good starting point for discussion, and Leaving aside the fact that a man may also have had encouraged others present to think more deeply about some complicity in this offence (for that was the the issues, which is one of our aims. culture of the age), stoning is suggested by the group / asked the group of local churchgoers what Christian values they linked with criminal justice. The first respondent folded his arms across his chest and said firmly "Punishment for sin". -

MEDIA ADVISORY: Thursday, August 11, 2011**

**MEDIA ADVISORY: Thursday, August 11, 2011** WWE SummerSlam Cranks Up the Heat at Participating Cineplex Entertainment Theatres Live, in High-Definition on Sunday, August 14, 2011 WHAT: Three championship titles are up for grabs, one will unify the prestigious WWE Championship this Sunday. Cineplex Entertainment, via our Front Row Centre Events, is pleased to announce WWE SummerSlam will be broadcast live at participating Cineplex theatres across Canada on Sunday, August 14, 2011 at 8:00 p.m. EDT, 7:00 p.m. CDT, 6:00 p.m. MDT and 5:00 p.m. PDT live from the Staples Center in Los Angeles, CA. Matches WWE Champion John Cena vs. WWE Champion CM Punk in an Undisputed WWE Championship Match World Heavyweight Champion Christian vs. Randy Orton in a No Holds Barred Match WWE Divas Champion Kelly Kelly vs. Beth Phoenix WHEN: Sunday, August 14, 2011 at 8:00 p.m. EDT, 7:00 p.m. CDT, 6:00 p.m. MDT and 5:00 p.m. PDT WHERE: Advance tickets are now available at participating theatre box offices, through the Cineplex Mobile Apps and online at www.cineplex.com/events or our mobile site m.cineplex.com. A special rate is available for larger groups of 20 or more. Please contact Cineplex corporate sales at 1-800-313-4461 or via email at [email protected]. The following 2011 WWE events will be shown live at select Cineplex Entertainment theatres: WWE Night of Champions September 18, 2011 WWE Hell in the Cell October 2, 2011 WWE Vengeance (formerly Bragging Rights) October 23, 2011 WWE Survivor Series November 20, 2011 WWE TLC: Tables, Ladders & Chairs December 18, 2011 -30- For more information, photos or interviews, please contact: Pat Marshall, Vice President, Communications and Investor Relations, Cineplex Entertainment, 416-323- 6648, [email protected] Kyle Moffatt, Director, Communications, Cineplex Entertainment, 416-323-6728, [email protected] . -

Understanding Women's Self-Promotion

UNDERSTANDING WOMEN’S SELF-PROMOTION DETRIMENTS: THE BACKLASH AVOIDANCE MODEL by CORINNE ALISON MOSS-RACUSIN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Psychology Written under the direction of Dr. Laurie A. Rudman And approved by ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2011 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Understanding Women’s Self-Promotion Detriments: The Backlash Avoidance Model. By CORINNE ALISON MOSS-RACUSIN Dissertation Director: Dr. Laurie A. Rudman Although self-promotion is necessary for career success, women experience backlash (i.e., social and economic penalties) for this behavior because it violates female gender stereotypes (Rudman, 1998). Moreover, women who fear backlash have difficulty with self-promotion, relative to men (Moss-Racusin & Rudman, 2010). The goal of this dissertation was to test the author’s backlash avoidance model (BAM), with the expectation that women’s beliefs that self-promotion violates female gender stereotypes lead them to fear backlash for this behavior, which in turn undermines their self- promotion abilities. Moreover, it was expected that the relationship between fear of backlash and self-promotion success would be at least partially mediated by self- regulatory focus (Crowe & Higgins, 1997) and perceived entitlement (Babcock & Laschever, 2003). To examine these ideas, Study 1 (N = 300) compared male and female participants’ performance on an essay-writing self-promotion task. As expected, women reported higher levels of fear of backlash and lower levels of self-promotion success than ii men. -

Must War Find a Way?167

Richard K. Betts A Review Essay Stephen Van Evera, Causes of War: Power and the Roots of Conict Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1999 War is like love, it always nds a way. —Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage tephen Van Evera’s book revises half of a fteen-year-old dissertation that must be among the most cited in history. This volume is a major entry in academic security studies, and for some time it will stand beside only a few other modern works on causes of war that aspiring international relations theorists are expected to digest. Given that political science syllabi seldom assign works more than a generation old, it is even possible that for a while this book may edge ahead of the more general modern classics on the subject such as E.H. Carr’s masterful polemic, 1 The Twenty Years’ Crisis, and Kenneth Waltz’s Man, the State, and War. Richard K. Betts is Leo A. Shifrin Professor of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University, Director of National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, and editor of Conict after the Cold War: Arguments on Causes of War and Peace (New York: Longman, 1994). For comments on a previous draft the author thanks Stephen Biddle, Robert Jervis, and Jack Snyder. 1. E.H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 2d ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1946); and Kenneth N. Waltz, Man, the State, and War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959). See also Waltz’s more general work, Theory of International Politics (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1979); and Hans J. -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H. -

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma?

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma? Robert Jervis xploring whether the Cold War was a security dilemma illumi- nates botEh history and theoretical concepts. The core argument of the security dilemma is that, in the absence of a supranational authority that can enforce binding agreements, many of the steps pursued by states to bolster their secu- rity have the effect—often unintended and unforeseen—of making other states less secure. The anarchic nature of the international system imposes constraints on states’ behavior. Even if they can be certain that the current in- tentions of other states are benign, they can neither neglect the possibility that the others will become aggressive in the future nor credibly guarantee that they themselves will remain peaceful. But as each state seeks to be able to pro- tect itself, it is likely to gain the ability to menace others. When confronted by this seeming threat, other states will react by acquiring arms and alliances of their own and will come to see the rst state as hostile. In this way, the inter- action between states generates strife rather than merely revealing or accentuat- ing con icts stemming from differences over goals. Although other motives such as greed, glory, and honor come into play, much of international politics is ultimately driven by fear. When the security dilemma is at work, interna- tional politics can be seen as tragic in the sense that states may desire—or at least be willing to settle for—mutual security, but their own behavior puts this very goal further from their reach.1 1. -

The Organizational Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms: Retrospect and Prospect Author(S): David A

The Organizational Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms: Retrospect and Prospect Author(s): David A. Welch Source: International Security , Fall, 1992, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Fall, 1992), pp. 112-146 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539170 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539170?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Security This content downloaded from 209.6.197.28 on Wed, 07 Oct 2020 15:39:26 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Organizational David A. Welch Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms Retrospect and Prospect 1991 marked the twentieth anniversary of the publication of Graham Allison's Essence of De- cision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. ' The influence of this work has been felt far beyond the study of international politics. Since 1971, it has been cited in over 1,100 articles in journals listed in the Social Sciences Citation Index, in every periodical touching political science, and in others as diverse as The American Journal of Agricultural Economics and The Journal of Nursing Adminis- tration.