Fall, 2009: Breeze Issue #39 Astro Boy Forever!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Representations and Reality: Defining the Ongoing Relationship Between Anime and Otaku Cultures By: Priscilla Pham

Representations and Reality: Defining the Ongoing Relationship between Anime and Otaku Cultures By: Priscilla Pham Submitted to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Contemporary Art, Design, and New Media Art Histories Toronto, Ontario, Canada, April 2021 © Priscilla Pham, 2021 Abstract This major research paper investigates the ongoing relationship between anime and otaku culture through four case studies; each study considers a single situation that demonstrates how this relationship changes through different interactions with representation. The first case study considers the early transmedia interventions that began to engage fans. The second uses Takashi Murakami’s theory of Superflat to connect the origins of the otaku with the interactions otaku have with representation. The third examines the shifting role of the otaku from that of consumer to producer by means of engagement with the hierarchies of perception, multiple identities, and displays of sexualities in the production of fan-created works. The final case study reflects on the 2.5D phenomenon, through which 2D representations are brought to 3D environments. Together, these case studies reveal the drivers of the otaku evolution and that the anime–otaku relationship exists on a spectrum that teeters between reality and representation. i Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my primary advisor, Ala Roushan, for her continued support and confidence in my writing throughout this paper’s development. Her constructive advice, constant guidance, and critical insights helped me form this paper. Thank you to Dr. David McIntosh, my secondary reader, for his knowledge on anime and the otaku world, which allowed me to change my perspective of a world that I am constantly lost in. -

Kotatsu Japanese Animation Film Festival 2017 in Partnership with the Japan Foundation

Kotatsu Japanese Animation Film Festival 2017 In partnership with the Japan Foundation Chapter - September 29th - October 1st, 2017 Aberystwyth Arts Centre – October 28th, 2017 The Largest Festival of Japanese Animation in Wales Announces Dates, Locations and Films for 2017 The Kotatsu Japanese Animation Festival returns to Wales for another edition in 2017 with audiences able to enjoy a whole host of Welsh premieres, a Japanese marketplace, and a Q&A and special film screening hosted by an important figure from the Japanese animation industry. The festival begins in Cardiff at Chapter Arts on the evening of Friday, September 29th with a screening of Masaaki Yuasa’s film The Night is Short, Walk on Girl (2017), a charming romantic romp featuring a love-sick student chasing a girl through the streets of Kyoto, encountering magic and weird situations as he does so. Festival head, Eiko Ishii Meredith will be on hand to host the opening ceremony and a party to celebrate the start of the festival which will last until October 01st and include a diverse array of films from near-future tales Napping Princess (2017) to the internationally famous mega-hit Your Name (2016). The Cardiff portion of the festival ends with a screening of another Yuasa film, the much-requested Mind Game (2004), a film definitely sure to please fans of surreal and adventurous animation. This is the perfect chance for people to see it on the big-screen since it is rarely screened. A selection of these films will then be screened at the Aberystywth Arts Centre on October 28th as Kotatsu helps to widen access to Japanese animated films to audiences in different locations. -

Animé & Tetsuwan Atomu

Lunds universitet Tina Davidsson Språk- och litteraturcentrum FIVK01 Filmvetenskap Handledare: Lars Gustaf Andersson 2011-01-21 Animé & Tetsuwan Atomu Japans första animerade superhjälte 1 INNEHÅLLSFÖRTECKING 1 INLEDNING....................................................................................................................................2 1.1 Vad är Animé?.............................................................................................................................2 1.2 Den unika animén.......................................................................................................................3 1.3 Syfte och frågeställningar ..........................................................................................................5 1.4 Avgränsning och disposition.......................................................................................................6 1.5 Metod och Teori..........................................................................................................................6 1.5 Tidigare forskning.......................................................................................................................8 2 BAKGRUND....................................................................................................................................9 2.1 Animés framväxt.........................................................................................................................9 2.2 Barn av sin tid: Genus...............................................................................................................11 -

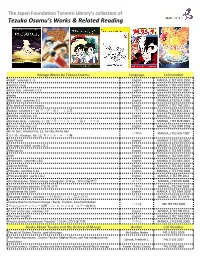

Tezuka Osamu Booklist

The Japan Foundation Toronto Library’s collection of Tezuka Osamu’s Works & Related Reading Manga Works by Tezuka Osamu Language Call number Adolf : volumes 1 - 5 English MANGA_E TEZ ADO 1995 Apollo's song English MANGA_E TEZ APO 2007 Astro boy : volumes 1-12 English MANGA_E TEZ AST 2002 Ayako English MANGA_E TEZ AYA 2010 Black Jack : volumes 1-3 English MANGA_E TEZ BLA 2008 The book of human insects English MANGA_E TEZ THE 2011 Budda : volumes 1~14 ブッダ:第1-14巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ BUD 2011 Buddha : volumes 1-8 English MANGA_E TEZ BUD 2003 Burakku Jakku : volumes 1~22 ブラックジャック:第1-22巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ BUR 2004 Dororo : Volumes 1-3 English MANGA_E TEZ DOR 2008 Hi no tori : Hinotori No. 12, Girisha, Roma hen 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ HIN 1987 火の鳥 : Hinotori. No. 12, ギリシャ・ローマ編 Lost World English MANGA_E TEZ LOS 2003 Message to Adolf : parts 1 & 2 English MANGA_E TEZ MES 2012 Metropolis English MANGA_E TEZ MET 2003 MW English MANGA_E TEZ MW 2007 Nextworld : volumes 1 &2 English MANGA_E TEZ NEX 2003 Ode to Kirihito English MANGA_E TEZ ODE 2006 Phoenix : volumes 1-12 English MANGA_E TEZ PHO 2003 Princess knight : parts 1 & 2 English MANGA_E TEZ PRI 2011 Shintakarajima : boken manga monogatari 新寳島 : 冒険漫画物語 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ SHI 2009 Shintakarajima tokuhon 新寶島 読本 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ SHI 2009 Swallowing the Earth English MANGA_E TEZ SWA 2009 Tetsuwan Atomu : volumes 1~17 鉄腕アトム:第 1-17 巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ TET 1979 Tezuka Osamu no Dizuni manga : Banbi, Pinokio : kara fukkokuban 日本語 REF TEZ TEZ 2005 手塚治虫のディズニー漫画 : バンビ, ピノキオ : カラー復刻版 Triton of the sea : volumes 1-2 English MANGA_E TEZ TRI 2013 The Twin Knights English MANGA_E TEZ TWI 2013 Tezuka Osamu kessakusen "kazoku"手塚治虫傑作選 家族 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ KAZ 2008 Books About Tezuka and the History of Manga Author Call Number The art of Osamu Tezuka : god of manga McCarthy, Helen 741.5 M32 2009 The Astro Boy essays : Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the manga/anime Schodt, Frederik L. -

Tezuka Dossier.Indd

Dossier de premsa Organitza Col·labora Del 31 d’octubre del 2019 al 6 de gener del 2020 Organitza i produeix: FICOMIC amb la col·laboració del Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya Comissari: Stéphane Beaujean Sala d’exposicions temporals 2 Astro Boy © Tezuka productions • El mangaka Osamu Tezuka, també conegut com a Déu del Manga per la seva immensa aportació a la vinyeta japonesa, és el protagonista d’una exposició que es podrà veure durant gairebé un parell de mesos al Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, i que està integrada per gairebé 200 originals d’aquest autor. • L’exposició ha estat produïda per FICOMIC gràcies a l’estreta col·laboració amb el Mu- seu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Tezuka Productions i el Festival de la Bande Desinneè d’Angulema. Osamu Tezuka, el Déu del Manga és una mostra sense precedents al nos- tre país, que vol donar a conèixer de més a prop l’obra d’un creador vital per entendre l’evolució del manga després de la Segona Guerra Mundial, i també a un dels autors de manga més prestigiosos i prolífi cs a nivell mundial. • Osamu Tezuka, el Déu del Manga es podrà visitar a partir del 31 d’octubre d’aquest any, coincidint amb l’inici de la 25a edició del Manga Barcelona, fi ns al 6 de gener de 2020. 3 Fénix © Tezuka productions Oda a Kirihito © Tezuka productions El còmic al Museu Nacional Aquest projecte forma part de l’acord de col·laboració entre FICOMIC i el Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya gràcies al qual també es va produir l’exposició Corto Maltés, de Juan Díaz Canales i Rubén Pellejero, o la més recent El Víbora. -

Nostalgia in Anime: Redefining Japanese Cultural Identity in Global Media Texts

NOSTALGIA IN ANIME: REDEFINING JAPANESE CULTURAL IDENTITY IN GLOBAL MEDIA TEXTS A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Communication, Culture and Technology By Susan S. Noh, B.A. Washington, DC April 24, 2017 Copyright 2017 by Susan S. Noh All Rights Reserved ii NOSTALGIA IN ANIME: REDEFINING JAPANESE CULTURAL IDENTITY IN GLOBAL MEDIA TEXT Susan S. Noh, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Michael S. Macovski, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Anime has become a ubiquitous facet of the transnational global media flow, and continues to serve as a unique and acknowledged example of a non-Western media form that has successfully penetrated the global market. Because of its remarkable popularity abroad and a trend towards invasive localization techniques, there have been observations made by Japanese culture scholars, such as Koichi Iwabuchi, who claim that anime is a stateless medium that is unsuitable for representing any true or authentic depiction of Japanese culture and identity. In this paper, I will be exploring this notion of statelessness within the anime medium and reveal how unique sociocultural tensions are reflected centrally within anime narratives or at the contextual peripheries, in which the narrative acts as an indirect response to larger societal concerns. In particular, I apply the notions of reflective and restorative nostalgia, as outlined by Svetlana Boym to reveal how modern Japanese identity is recreated and redefined through anime. In this sense, while anime may appeal to a larger global public, it is far from being a culturally stateless medium. -

The Problematic Internationalization Strategy of the Japanese Manga

By Ching-Heng Melody Tu Configuring Appropriate Support: The Problematic Internationalization Strategy of the Japanese Manga and Anime Industry Global Markets, Local Creativities Master’s Program at Erasmus University Rotterdam Erasmus University Rotterdam 2019/7/10 Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction ............................................................................................. 4 1.1 Purpose .................................................................................................. 6 1.2 Research Question ................................................................................. 7 1.3 Conceptual Framework ........................................................................ 10 1.4 The Research Method .......................................................................... 12 1.5 Research Scope and Limitation of the Study ......................................... 13 1.5.1 Research Scope ............................................................................... 13 1.5.2 Limitations of the Study .................................................................. 14 1.6 Definition of Terms .............................................................................. 15 1.6.1 Manga ............................................................................................. 15 1.6.2 Anime.............................................................................................. 15 1.6.3 Fansub ............................................................................................ 16 1.7 -

Manga Shōnen

Manga Shnen: Kat Ken'ichi and the Manga Boys Ryan Holmberg Mechademia, Volume 8, 2013, pp. 173-193 (Article) Published by University of Minnesota Press DOI: 10.1353/mec.2013.0010 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mec/summary/v008/8.holmberg.html Access provided by University of East Anglia (12 Mar 2014 14:30 GMT) Twenty First Century Adventure, Twin Knight (Sequel to Princess Knight), Under the Air, Unico, The Vampires, Volcanic Eruption, The The Adventure of Rock, Adventure of Rubi, The Age of Adventure, The Age of Great Floods, Akebono-san, Alabaster, The Amazing 3, Ambassador Magma, Angel Gunfighter, Angel's Hill, Ant and the Giant, Apollo's Song, Apple with Watch Mechanism, Astro Boy, Ayako, Bagi, Boss of the Earth, Barbara, Benkei, Big X, Biiko-chan, Birdman Anthology, Black Jack, Bomba!, Boy Detective Zumbera, Brave Dan, Buddha, Burunga I, Captain Atom, Captain Ken, Captain Ozma, Chief Detective Kenichi, Cave-in, Crime and Punishment, The Curtain is Still Blue Tonight, DAmons, The Detective Rock Home, The Devil Garon, The Devil of the Earth, Diary of Ma-chan, Don Dracula, Dororo, Dotsuitare, Dove, Fly Up to Heaven, Dr. Mars, Dr. Thrill, Duke Goblin, Dust Eight, Elephant's Kindness, Elephant's Sneeze, Essay on Idleness of Animals, The Euphrates Tree, The Fairy of Storms, Faust, The Film Lives On, Fine Romance, Fire of Tutelary God, Fire Valley, Fisher, Flower & Barbarian, Flying Ben, Ford 32 years Type, The Fossil Island, The Fossil Man, The Fossil Man Strikes Back, Fountain of Crane, Four Card, Four Fencers of the Forest, Fuku-chan in 21st Century, Fusuke, FuturemanRYAN HOLMBERG Kaos, Gachaboi's Record of One Generation, Game, Garbage War, Gary bar pollution record, General Onimaru, Ghost, Ghost in jet base, Ghost Jungle, Ghost story at 1p.m., Gikko-chan and Makko-chan, Giletta, Go Out!, God Father's son, Gold City, Gold Scale, Golden Bat, The Golden Trunk, Good bye, Mali, Good bye, Mr. -

The Manifestation of Classism in the Astro Boy Animation

Jurnal LINGUA SUSASTRA e-ISSN:2746-704X vol. 1, no. 2, 2020 p. 82-91 The Manifestation of Classism in the Astro Boy Animation Yessi Ratna Sari1,*, Genta Iverstika Gempita2 AMIK Mitra Gama1, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia2 *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Utopia is an appropriate word to describe about the ideal, worthy, and perfect life depicted in a city called Metro City in the Astro Boy animation. This study examines the animation movie Astro Boy and how the world that is being told in the works could be defined as Utopian world like it is being described through the movie. The purpose of this study is to proof whether the setting successfully conveyed the Utopian world or whether it still has some deficiency as Utopian is known as impossibly perfect world to be created. The corpus of this study is the movie of Astro Boy focuses on the setting and relationship between human kind and robots. This research uses a qualitative descriptive method which describes social phenomena by conducting in-depth understanding and analysis. The aims of this research is to analyze more deeply the picture contained in the animation, which shows how humans and robots are able to create a new world also coexist. Moreover, the conceptual framework that will be use is the theory of Capitalism and Classism in order to examine the setting of Utopian world. Key words. Utopia, utopian world, classism, capitalism, Astro Boy Abstrak. Utopia adalah kata yang tepat untuk menggambarkan kehidupan yang ideal, layak, dan sempurna yang digambarkan di kota bernama Metro City dalam animasi Astro Boy. -

Adolf: a Representação Do Militarismo Japonês Sob a Perspectiva De Osamu Tezuka

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTÓRIA RODOLFO MARINHO GREEN (11\0139062) ADOLF: A REPRESENTAÇÃO DO MILITARISMO JAPONÊS SOB A PERSPECTIVA DE OSAMU TEZUKA Brasília 2018 RODOLFO MARINHO GREEN (11/0139062) ADOLF: A REPRESENTAÇÃO DO MILITARISMO JAPONÊS SOB A PERSPECTIVA DE OSAMU TEZUKA Artigo apresentado ao Departamento de História do Instituto de Ciências Humanas da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial para a obtenção do grau de licenciado em História. Orientador: Prof. Antônio José Barbosa Brasília 2018 Resumo O presente trabalho aborda sobre o mangá Adolf de Osamu Tezuka (1926-1989) e de sua narrativa. O artigo pretende desenvolver o contexto histórico do mangá e paralelamente, traçar uma análise de seus personagens baseando-se nos traços de Tezuka e a sua repercussão na sociedade japonesa contemporânea. A obra, em seu conteúdo, apresenta uma forma sutil e impactante, emitindo um alerta para a humanidade não regredir ao seu passado sanguinário. Palavras-Chave: Mangá; Japão; Fascimo; Adolf; Tezuka Abstract The present work approaches the manga Adolf by Osamu Tezuka (1926-1989) and your narrative. The article intends to develop the historical context of the manga and parallel, draw an analysis of your characters to base in your traits and your repercussion in the Japanese contemporary society. The work in your content presents a subtle form and shocking, issuing an alert for humanity not taking steps backwards for their bloody past. Key-Words: Manga; Japan; Fascism; Adolf; Tezuka 4 1. Introdução O mangá representa para o povo japonês o expoente máximo de sua cultura, tornando- se o principal exportador cultural do Japão, marcando presença no cotidiano desta sociedade. -

Bibliographie Du Fonds Japonais

L’illustration japonaise Sélection d’albums, de documentaires et de livres animés 1 Ce fonds est une sélection d’albums, de livres documentaires et de livres animés japonais datant des années 70 à nos jours. Il est constitué d’une centaine d’ouvrages entièrement en japonais et est uniquement disponible à la consultation sur place. Les albums et les livres documentaires sont disponibles en rayon au centre de l’illustration. Les livres animés sont conservés en magasin et disponibles sur demande préalable. ALBUMS Chiru Chiru no ichi nichi [= Une journée avec Chiru Chiru] / Yukimi Konno Skyfish Graphix, 2000 Une longue journée attend Chiru Chiru. Que va-t-elle bien pouvoir se mettre ? Que va- t-elle se cuisiner ? Un livre destiné aux plus petits. San San San [= Sun Sun Sun] / Misao Kobayashi Skyfish Graphix, 2001 Mi-chan a un ami qu’elle garde toujours auprès d’elle : un soleil de poche. Celui-ci l’accompagne partout : il lui tient chaud lorsqu’elle fait des bonhommes de neige en hiver, il lui évite d’avoir peur la nuit, … Kikimimi zukin / Junji Kinoshita et Shigeru Hatsuyama Iwanami Shoten, 1994 [1956] Tôroku a beaucoup de travail, mais quelque chose l’intrigue : qu’essaient de lui dire tous ces oiseaux ? Fushigi na tai ? [= Le tambourin magique] / Momoko Ishii et Kon Shimizu Iwanami Shoten, 1992 [1953] Il y a fort longtemps, un homme nommé Gengorô possédait un tambourin aux propriétés étranges. Lorsqu’il en jouait, il pouvait par exemple faire pousser les fleurs en quelques minutes. O tsuki-sama Konban wa [= Bonsoir madame la Lune] / Akiko Hayashi Fukuinkan Shoten, 1995 [1986] A la nuit tombée, la lune apparaît.