On the Anticipation of Ethical Conflicts Between Humans and Robots in Japanese Mangas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Fun Facts and Activities

Robo Info: Fun Facts and Activities By: J. Jill Rogers & M. Anthony Lewis, PhD Robo Info: Robot Activities and Fun Facts By: J. Jill Rogers & M. Anthony Lewis, PhD. Dedication To those young people who dare to dream about the all possibilities that our future holds. Special Thanks to: Lauren Buttran and Jason Coon for naming this book Ms. Patti Murphy’s and Ms. Debra Landsaw’s 6th grade classes for providing feedback Liudmila Yafremava for her advice and expertise i Iguana Robotics, Inc. PO Box 625 Urbana, IL 61803-0625 www.iguana-robotics.com Copyright 2004 J. Jill Rogers Acknowledgments This book was funded by a research Experience for Teachers (RET) grant from the National Science Foundation. Technical expertise was provided by the research scientists at Iguana Robotics, Inc. Urbana, Illinois. This book’s intended use is strictly for educational purposes. The author would like to thank the following for the use of images. Every care has been taken to trace copyright holders. However, if there have been unintentional omissions or failure to trace copyright holders, we apologize and will, if informed, endeavor to make corrections in future editions. Key: b= bottom m=middle t=top *=new page Photographs: Cover-Iguana Robotics, Inc. technical drawings 2003 t&m; http://robot.kaist.ac.kr/~songsk/robot/robot.html b* i- Iguana Robotics, Inc. technical drawings 2003m* p1- http://www.history.rochester.edu/steam/hero/ *p2- Encyclopedia Mythica t *p3- Museum of Art Neuchatel t* p5- (c) 1999-2001 EagleRidge Technologies, Inc. b* p9- Copyright 1999 Renato M.E. Sabbatini http://www.epub.org.br/cm/n09/historia/greywalter_i.htm t ; http://www.ar2.com/ar2pages/uni1961.htm *p10- http://robot.kaist.ac.kr/~songsk/robot/robot.html /*p11- http://robot.kaist.ac.kr/~songsk/robot/robot.html; Sojourner, http://marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov/home/ *p12- Sony Aibo, The Sony Corporation of America, 550 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10022 t; Honda Asimo, Copyright, 2003 Honda Motor Co., Ltd. -

Design and Realization of a Humanoid Robot for Fast and Autonomous Bipedal Locomotion

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN Lehrstuhl für Angewandte Mechanik Design and Realization of a Humanoid Robot for Fast and Autonomous Bipedal Locomotion Entwurf und Realisierung eines Humanoiden Roboters für Schnelles und Autonomes Laufen Dipl.-Ing. Univ. Sebastian Lohmeier Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät für Maschinenwesen der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktor-Ingenieurs (Dr.-Ing.) genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Udo Lindemann Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Heinz Ulbrich 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr.-Ing. Horst Baier Die Dissertation wurde am 2. Juni 2010 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät für Maschinenwesen am 21. Oktober 2010 angenommen. Colophon The original source for this thesis was edited in GNU Emacs and aucTEX, typeset using pdfLATEX in an automated process using GNU make, and output as PDF. The document was compiled with the LATEX 2" class AMdiss (based on the KOMA-Script class scrreprt). AMdiss is part of the AMclasses bundle that was developed by the author for writing term papers, Diploma theses and dissertations at the Institute of Applied Mechanics, Technische Universität München. Photographs and CAD screenshots were processed and enhanced with THE GIMP. Most vector graphics were drawn with CorelDraw X3, exported as Encapsulated PostScript, and edited with psfrag to obtain high-quality labeling. Some smaller and text-heavy graphics (flowcharts, etc.), as well as diagrams were created using PSTricks. The plot raw data were preprocessed with Matlab. In order to use the PostScript- based LATEX packages with pdfLATEX, a toolchain based on pst-pdf and Ghostscript was used. -

Can a Robot Be Perceived As a Developing Creature?

538 HUMAN COMMUNICATION RESEARCH / October 2005 Can a Robot Be Perceived as a Developing Creature? Effects of a Robot’s Long-Term Cognitive Developments on Its Social Presence and People’s Social Responses Toward It KWAN MIN LEE NAMKEE PARK HAYEON SONG University of Southern California This study tests the effect of long-term artifi cial development of a robot on users’ feelings of social presence and social responses toward the robot. The study is a 2 (developmental capability: developmental versus fully matured) x 2 (number of participants: individual ver- sus group) between-subjects experiment (N = 40) in which participants interact with Sony’s robot dog, AIBO, for a month. The results showed that the developmental capability factor had signifi cant positive impacts on (a) perceptions of AIBO as a lifelike creature, (b) feel- ings of social presence, and (c) social responses toward AIBO. The number of participants factor, however, affected only the parasocial relationship and the buying intention variables. No interaction between the two factors was found. The results of a series of path analyses showed that feelings of social presence mediated participants’ social responses toward AIBO. We discuss implications of the current study on human–robot interaction, the computers are social actors (CASA) paradigm, and the study of (tele)presence. obots, once imagined only in science-fi ction fi lms, are now being used for various purposes. New applications of robots in thera- Rpeutic, educational, and entertainment environments have caused an important shift in the study of human–robot interaction (HRI). Rather than viewing robots as mere tools or senseless machines, researchers are beginning to see robots as social actors that can autonomously interact with humans in a socially meaningful way. -

Representations and Reality: Defining the Ongoing Relationship Between Anime and Otaku Cultures By: Priscilla Pham

Representations and Reality: Defining the Ongoing Relationship between Anime and Otaku Cultures By: Priscilla Pham Submitted to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Contemporary Art, Design, and New Media Art Histories Toronto, Ontario, Canada, April 2021 © Priscilla Pham, 2021 Abstract This major research paper investigates the ongoing relationship between anime and otaku culture through four case studies; each study considers a single situation that demonstrates how this relationship changes through different interactions with representation. The first case study considers the early transmedia interventions that began to engage fans. The second uses Takashi Murakami’s theory of Superflat to connect the origins of the otaku with the interactions otaku have with representation. The third examines the shifting role of the otaku from that of consumer to producer by means of engagement with the hierarchies of perception, multiple identities, and displays of sexualities in the production of fan-created works. The final case study reflects on the 2.5D phenomenon, through which 2D representations are brought to 3D environments. Together, these case studies reveal the drivers of the otaku evolution and that the anime–otaku relationship exists on a spectrum that teeters between reality and representation. i Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my primary advisor, Ala Roushan, for her continued support and confidence in my writing throughout this paper’s development. Her constructive advice, constant guidance, and critical insights helped me form this paper. Thank you to Dr. David McIntosh, my secondary reader, for his knowledge on anime and the otaku world, which allowed me to change my perspective of a world that I am constantly lost in. -

Entertainment Robots Market Research Report - Global Forecast Till 2027

Report Information More information from: https://www.marketresearchfuture.com/reports/2925 Entertainment Robots Market Research Report - Global Forecast till 2027 Report / Search Code: MRFR/SEM/2149-CR Publish Date: February, 2020 Request Sample Price 1-user PDF : $ 4450.0 Enterprise PDF : $ 6250.0 Description: Entertainment Robots Market Overview The Entertainment Robots Market is expected to project at USD 3715.29 million and account at a CAGR of 23.06% during the forecast period of 2018 to 2023. The entertainment robots are specially manufactured for recreational purposes and are primarily important in the commercial and entertainment industry. These entertainment robots entertain people and especially kids by dancing, singing, and telling stories. Some of the famous robots in the entertainment industry so served for entertainment purposes are AIBO, Poo-Chi, iDOG, Bo-Wow, Gupi, Teksta, and i-Cybie are some of the important tools so served. The entertainment robots which come under the personal robotics market developed for utilitarian purposes, and also for recreational, commercial, and for entertainment purposes. Covid 19 Analysis The entertainment robots market experiences a declination in its production during the pandemic of COVID. COVID had a great impact on the manufacturing unit. A decrease in shortages of labor was marked. The outbreak also decreased the demand for production from end-users industries.The government imposed strict rules and regulations. He put forward the work from home initiatives for the employees. Wearing up masks and gloves was made compulsory and also strict actions were taken against those who tried violating the rules. Market Dynamics Drivers Rise in the growth of artificial intelligence technology, improving the growth of the geriatric population, and increasing the demand for animatronics pushes up the entertainment robots market. -

Kotatsu Japanese Animation Film Festival 2017 in Partnership with the Japan Foundation

Kotatsu Japanese Animation Film Festival 2017 In partnership with the Japan Foundation Chapter - September 29th - October 1st, 2017 Aberystwyth Arts Centre – October 28th, 2017 The Largest Festival of Japanese Animation in Wales Announces Dates, Locations and Films for 2017 The Kotatsu Japanese Animation Festival returns to Wales for another edition in 2017 with audiences able to enjoy a whole host of Welsh premieres, a Japanese marketplace, and a Q&A and special film screening hosted by an important figure from the Japanese animation industry. The festival begins in Cardiff at Chapter Arts on the evening of Friday, September 29th with a screening of Masaaki Yuasa’s film The Night is Short, Walk on Girl (2017), a charming romantic romp featuring a love-sick student chasing a girl through the streets of Kyoto, encountering magic and weird situations as he does so. Festival head, Eiko Ishii Meredith will be on hand to host the opening ceremony and a party to celebrate the start of the festival which will last until October 01st and include a diverse array of films from near-future tales Napping Princess (2017) to the internationally famous mega-hit Your Name (2016). The Cardiff portion of the festival ends with a screening of another Yuasa film, the much-requested Mind Game (2004), a film definitely sure to please fans of surreal and adventurous animation. This is the perfect chance for people to see it on the big-screen since it is rarely screened. A selection of these films will then be screened at the Aberystywth Arts Centre on October 28th as Kotatsu helps to widen access to Japanese animated films to audiences in different locations. -

Animé & Tetsuwan Atomu

Lunds universitet Tina Davidsson Språk- och litteraturcentrum FIVK01 Filmvetenskap Handledare: Lars Gustaf Andersson 2011-01-21 Animé & Tetsuwan Atomu Japans första animerade superhjälte 1 INNEHÅLLSFÖRTECKING 1 INLEDNING....................................................................................................................................2 1.1 Vad är Animé?.............................................................................................................................2 1.2 Den unika animén.......................................................................................................................3 1.3 Syfte och frågeställningar ..........................................................................................................5 1.4 Avgränsning och disposition.......................................................................................................6 1.5 Metod och Teori..........................................................................................................................6 1.5 Tidigare forskning.......................................................................................................................8 2 BAKGRUND....................................................................................................................................9 2.1 Animés framväxt.........................................................................................................................9 2.2 Barn av sin tid: Genus...............................................................................................................11 -

Mixed Reality Technologies for Novel Forms of Human-Robot Interaction

Dissertation Mixed Reality Technologies for Novel Forms of Human-Robot Interaction Dissertation with the aim of achieving a doctoral degree at the Faculty of Mathematics, Informatics and Natural Sciences Dipl.-Inf. Dennis Krupke Human-Computer Interaction and Technical Aspects of Multimodal Systems Department of Informatics Universität Hamburg November 2019 Review Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Frank Steinicke Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Jianwei Zhang Drittgutachter: Prof. Dr. Eva Bittner Vorsitzende der Prüfungskomission: Prof. Dr. Simone Frintrop Datum der Disputation: 17.08.2020 “ My dear Miss Glory, Robots are not people. They are mechanically more perfect than we are, they have an astounding intellectual capacity, but they have no soul.” Karel Capek Abstract Nowadays, robot technology surrounds us and future developments will further increase the frequency of our everyday contacts with robots in our daily life. To enable this, the current forms of human-robot interaction need to evolve. The concept of digital twins seems promising for establishing novel forms of cooperation and communication with robots and for modeling system states. Machine learning is now ready to be applied to a multitude of domains. It has the potential to enhance artificial systems with capabilities, which so far are found in natural intelligent creatures, only. Mixed reality experienced a substantial technological evolution in recent years and future developments of mixed reality devices seem to be promising, as well. Wireless networks will improve significantly in the next years and thus, latency and bandwidth limitations will be no crucial issue anymore. Based on the ongoing technological progress, novel interaction and communication forms with robots become available and their application to real-world scenarios becomes feasible. -

Social Robotics Agenda.Pdf

Thank you! The following agenda for social robotics was developed in a project led by KTH and funded by Vinnova. It is a result of cooperation between the following 35 partners: Industry: ABB, Artificial Solutions, Ericsson, Furhat robotics, Intelligent Machines, Liquid Media, TeliaSonera Academia: Göteborgs universitet, Högskolan i Skövde, Karolinska Institutet, KTH, Linköpings universitet, Lunds tekniska högskola, Lunds Universitet, Röda korsets högskola, Stockholms Universtitet, Uppsala Universitet, Örebro universitet Public sector: Institutet för Framtidsstudier, Myndigheten för Delaktighet, Myndigheten för Tillgängliga Medier, Statens medicinsk- etiska råd, Robotdalen, SLL Innovation, Språkrådet End-user organistions: Brostaden, Epicenter, EF Education First, Fryshuset Gymnasium, Hamnskolan, Investor, Kunskapsskolan, Silver Life, Svenskt demenscentrum, Tekniska Museet We would like to thank all partners for their great commitment at the workshops where they shared good ideas and insightful experiences, as well as valuable and important observations of what the future might hold. Agenda key persons: Joakim Gustafson (KTH), Peje Emilsson (Silver Life), Jan Gulliksen (KTH), Mikael Hedelind (ABB), Danica Kragic (KTH), Per Ljunggren (Intelligent Machines), Amy Loutfi (Örebro university), Erik Lundqvist (Robotdalen), Stefan Stern (Investor), Karl-Erik Westman (Myndigheten för Delaktighet), Britt Östlund (KTH) Writing group: editor Joakim Gustafson, co-editor Jens Edlund, Jonas Beskow, Mikael Hedelind, Danica Kragic, Per Ljunggren, Amy -

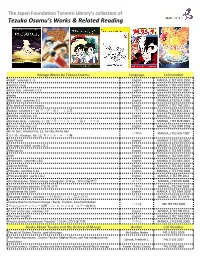

Tezuka Osamu Booklist

The Japan Foundation Toronto Library’s collection of Tezuka Osamu’s Works & Related Reading Manga Works by Tezuka Osamu Language Call number Adolf : volumes 1 - 5 English MANGA_E TEZ ADO 1995 Apollo's song English MANGA_E TEZ APO 2007 Astro boy : volumes 1-12 English MANGA_E TEZ AST 2002 Ayako English MANGA_E TEZ AYA 2010 Black Jack : volumes 1-3 English MANGA_E TEZ BLA 2008 The book of human insects English MANGA_E TEZ THE 2011 Budda : volumes 1~14 ブッダ:第1-14巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ BUD 2011 Buddha : volumes 1-8 English MANGA_E TEZ BUD 2003 Burakku Jakku : volumes 1~22 ブラックジャック:第1-22巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ BUR 2004 Dororo : Volumes 1-3 English MANGA_E TEZ DOR 2008 Hi no tori : Hinotori No. 12, Girisha, Roma hen 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ HIN 1987 火の鳥 : Hinotori. No. 12, ギリシャ・ローマ編 Lost World English MANGA_E TEZ LOS 2003 Message to Adolf : parts 1 & 2 English MANGA_E TEZ MES 2012 Metropolis English MANGA_E TEZ MET 2003 MW English MANGA_E TEZ MW 2007 Nextworld : volumes 1 &2 English MANGA_E TEZ NEX 2003 Ode to Kirihito English MANGA_E TEZ ODE 2006 Phoenix : volumes 1-12 English MANGA_E TEZ PHO 2003 Princess knight : parts 1 & 2 English MANGA_E TEZ PRI 2011 Shintakarajima : boken manga monogatari 新寳島 : 冒険漫画物語 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ SHI 2009 Shintakarajima tokuhon 新寶島 読本 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ SHI 2009 Swallowing the Earth English MANGA_E TEZ SWA 2009 Tetsuwan Atomu : volumes 1~17 鉄腕アトム:第 1-17 巻 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ TET 1979 Tezuka Osamu no Dizuni manga : Banbi, Pinokio : kara fukkokuban 日本語 REF TEZ TEZ 2005 手塚治虫のディズニー漫画 : バンビ, ピノキオ : カラー復刻版 Triton of the sea : volumes 1-2 English MANGA_E TEZ TRI 2013 The Twin Knights English MANGA_E TEZ TWI 2013 Tezuka Osamu kessakusen "kazoku"手塚治虫傑作選 家族 日本語 MANGA_J TEZ KAZ 2008 Books About Tezuka and the History of Manga Author Call Number The art of Osamu Tezuka : god of manga McCarthy, Helen 741.5 M32 2009 The Astro Boy essays : Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the manga/anime Schodt, Frederik L. -

Robótica De Serviciso: Tendencias

KUKA – from Industrial to Service Robotics . Dr. Johannes Kurth Head of Research & Predevelopment Dr. Tim Guhl Project Manager Cooperative Research Projects KUKA Roboter GmbH, Augsburg, Germany . Sr. Miquel López Director Técnico KUKA Robots Ibérica, S. A. Overview . Introduction . KUKA Roboter GmbH . Industrial Robots and their applications . Innovation leadership . KUKA on the way from Industrial to Service Robotics . Strategy . KUKA Products for Research & Education . KUKA Lightweight Robot + FRI . youBot . Medical Robots . KUKA Products for Entertainment . Robocoaster . Summary and conclusions KUKA – from Industrial to Service Robotics KUKA Roboter GmbH | Miquel López | 27.06.2014 | Page 3 www.kuka-robotics.com KUKA Robotics Robots Controllers Software Applications Service Platforms KUKA – from Industrial to Service Robotics KUKA Roboter GmbH | Miquel López | 27.06.2014 | Page 4 www.kuka-robotics.com KUKA Robotics – Product range KUKA – from Industrial to Service Robotics KUKA Roboter GmbH | Miquel López | 27.06.2014 | Page 5 www.kuka-robotics.com KUKA Robotics – Automotive Leading supplier to the Automotive industry . Long-standing customer relationships . Ability to customize standard products . Joint solution developments . Innovation leadership . Market leadership . Technological innovation and cost reduction drive customer demand KUKA – from Industrial to Service Robotics KUKA Roboter GmbH | Miquel López | 27.06.2014 | Page 6 www.kuka-robotics.com KUKA Robotics – Automotive Assembly Coating & bonding Cutting Deburring Handling