Experience/Materiality/Articulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2018 XXIV

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEARBOOK FACTS AND FIGURES ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XXIV (51) 2018 TALLINN 2019 This book was compiled by: Jaak Järv (editor-in-chief) Editorial team: Siiri Jakobson, Ebe Pilt, Marika Pärn, Tiina Rahkama, Ülle Raud, Ülle Sirk Translator: Kaija Viitpoom Layout: Erje Hakman Photos: Annika Haas p. 30, 31, 48, Reti Kokk p. 12, 41, 42, 45, 46, 47, 49, 52, 53, Janis Salins p. 33. The rest of the photos are from the archive of the Academy. Thanks to all authos for their contributions: Jaak Aaviksoo, Agnes Aljas, Madis Arukask, Villem Aruoja, Toomas Asser, Jüri Engelbrecht, Arvi Hamburg, Sirje Helme, Marin Jänes, Jelena Kallas, Marko Kass, Meelis Kitsing, Mati Koppel, Kerri Kotta, Urmas Kõljalg, Jakob Kübarsepp, Maris Laan, Marju Luts-Sootak, Märt Läänemets, Olga Mazina, Killu Mei, Andres Metspalu, Leo Mõtus, Peeter Müürsepp, Ülo Niine, Jüri Plado, Katre Pärn, Anu Reinart, Kaido Reivelt, Andrus Ristkok, Ave Soeorg, Tarmo Soomere, Külliki Steinberg, Evelin Tamm, Urmas Tartes, Jaana Tõnisson, Marja Unt, Tiit Vaasma, Rein Vaikmäe, Urmas Varblane, Eero Vasar Printed in Priting House Paar ISSN 1406-1503 (printed version) © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA ISSN 2674-2446 (web version) CONTENTS FOREWORD ...........................................................................................................................................5 CHRONICLE 2018 ..................................................................................................................................7 MEMBERSHIP -

Estonian Art 1/2013 (32)

Estonian 1/2013Art 1 Evident in Advance: the maze of translations Merilin Talumaa, Marie Vellevoog 4 Evident in Advance, or lost (and gained) in translation(s)? Daniele Monticelli 7 Neeme Külm in abstract autarchic ambience Johannes Saar 9 Encyclopaedia of Erki Kasemets Andreas Trossek 12 Portrait of a woman in the post-socialist era (and some thoughts about nationalism) Jaana Kokko 15 An aristocrat’s desires are always pretty Eero Epner 18 Collecting that reassesses value at the 6th Tallinn Applied Art Triennial Ketli Tiitsar 20 Comments on The Art of Collecting Katarina Meister, Lylian Meister, Tiina Sarapu, Marit Ilison, Kaido Ole, Krista Leesi, Jaanus Samma 24 “Anu, you have Estonian eyes”: textile artist Anu Raud and the art of generalisation Elo-Hanna Seljamaa Insert: An Education Veronika Valk 27 Authentic deceleration – smart textiles at an exhibition Thomas Hollstein 29 Fear of architecture Karli Luik 31 When the EU grants are distributed, the muses are silent Piret Lindpere 34 Great expectations Eero Epner’s interview with Mart Laidmets 35 Thoughts on a road about roads Margit Mutso 39 The meaning of crossroads in Estonian folk belief Ülo Valk 42 Between the cult of speed and scenery Katrin Koov 44 The seer meets the maker Giuseppe Provenzano, Arne Maasik 47 The art of living Jan Kaus 49 Endel Kõks against the background of art-historical anti-fantasies Kädi Talvoja 52 Exhibitions Estonian Art is included All issues of Estonian Art are also available on the Internet: http://www.estinst.ee/eng/estonian-art-eng/ in Art and Architecture Complete (EBSCO). Front cover: Dénes Farkas. -

An Examination of the Role of Nationalism in Estonia’S Transition from Socialism to Capitalism

De oeconomia ex natione: An Examination of the Role of Nationalism in Estonia’s Transition from Socialism to Capitalism Thomas Marvin Denson IV Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Besnik Pula, Committee Chair Courtney I.P. Thomas Charles L. Taylor 2 May 2017 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Estonia, post-Soviet, post-socialist, neoliberalism, nationalism, nationalist economy, soft nativism Copyright © 2017 by Thomas M. Denson IV De oeconomia ex natione: An Examination of the Role of Nationalism in Estonia’s Transition from Socialism to Capitalism Thomas Marvin Denson IV Abstract This thesis explores the role played by nationalism in Estonia’s transition to capitalism in the post-Soviet era and the way it continues to impact the Estonian economy. I hypothesize that nationalism was the key factor in this transition and that nationalism has placed a disproportionate economic burden on the resident ethnic Russians. First, I examine the history of Estonian nationalism. I examine the Estonian nationalist narrative from its beginning during the Livonian Crusade, the founding of Estonian nationalist thought in the late 1800s with a German model of nationalism, the conditions of the Soviet occupation, and the role of song festivals in Estonian nationalism. Second, I give a brief overview of the economic systems of Soviet and post-Soviet Estonia. Finally, I examine the impact of nationalism on the Estonian economy. To do this, I discuss the nature of nationalist economy, the presence of an ethno-national divide between the Estonians and Russians, and the impact of nationalist policies in citizenship, education, property rights, and geographical location. -

VIRGE LOO PORTFOLIO Virgeloo.Tumblr.Com [email protected]

VIRGE LOO PORTFOLIO virgeloo.tumblr.com [email protected] SAH SAH (2015) Sah Sah explores ideas about our connectedness with environments by looking at sound as a phenomena that is able to shape our nature in a longer period of time. The title derives from an Estonian word “sahin” which describes the sound of rustling tree leaves. This inspiring natural phenomena is the core of a personal sound memory and is related to artist’s cultural background. This art project gives a peek into a Nordic mindset and investigates if a geocultural phenomena could be universally perceived. An interwoven set of works were created by visualising the characteristics of sound in a still image and using these painted images to set the sound in motion again – thus creating a circle of transitions. Sah Sah consists of ink paintings, video and sound. The sound was designed by Sander Saarmets. Sah Sah consists of series of seven large scale (95x180cm) and 45 smaller (30x20cm) ink paintings. Sah Sah video (10:10) was made in collaboration with Sander Saarmets. Video: youtu.be/_ctjiDVyq84 Works shown at solo exhibition SAH SAH 8/05 – 12/05/2015 thesahsahs.tumblr.com WORK IN PROGRESS (2015) Work in Progress focused on my creative process. By mapping various elements and activities involved in creating a finalised artwork, the audience got a glimpse into artist’s creative process. The visually organised “mind map” on a blackboard was a temporary and developing (representation of) work in progress. The exhibition space was set up like a studio, with tools and objects, unfinished potential artworks and leftovers. -

Post-Soviet Art Museums in the Era of Globalization

Kunsthaus Graz, Graz University Post-Soviet Art Museums in the Era of Globalization Contemporary Art + Institutions International conference Friday, June 18 – Saturday, June 19, 2010 June 18, 10–18, June 19, 10–15 Kunsthaus Graz, Space04 Organized by Graz University in cooperation with Kunsthaus Graz Waltraud Bayer, Graz University; Peter Pakesch, Kunsthaus Graz Conference language: English Kunsthaus Graz, Universalmuseum Joanneum, Lendkai 1, 8020 Graz T +43–316/8017-9200, Tuesday–Sunday 10am–6pm [email protected], www.museum-joanneum.at This text is published on the occasion of After 1990/91, with the end of Communist cultural the international conference policy, art museums in the former USSR were faced Post-Soviet Art Museums with stifling financial problems, new demands of an in the Era of Globalization Contemporary Art + Institutions abruptly emerging Capitalist market economy and Friday, June 18 – the urgent need to restructure as institutions. Yet, Saturday, June 19, 2010 the dismal financial and institutional conditions were accompanied by an unprecedented amount of intellectual-artistic freedom as well as by open bor- ders, unlimited access to hitherto unavailable (or tabooed) information, and direct contact with the Western art world. With traditional values and ideo- logical guidelines abandoned, new contexts, new territories, and new orders were explored. Museums proved receptive to global trends. This interdisciplinary conference will conquer new terrain – both thematically and methodologically. It addresses and analyses the fundamental transfor- mation process in the field of contemporary art – a process initiated by the now legendary auction organized by Sotheby’s in Moscow, 1988. The auction led to a politically motivated reassessment and com- mercial appreciation of art which until then had been associated with political dissent. -

Eka Booklet.Indd

International Master's Programmes CONTENTS 3 Welcome 4 Postgraduate Studies in English 6 MA in Design and Crafts 10 MA in Animation 14 MA in Interaction Design 18 MA in Interior Architecture 22 MA in Urban Studies 26 MSc in Design and Engineering 30 Apply and Contact ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS INTERNATIONAL MASTER'S PROGRAMMES An Island of Freedom It is possible to become a good artist without an art school diploma, but it is more sensible to get an education and easier for society to trust an expert or skilled practitioner. A Master’s degree does not automatically make someone’s art or ideas bett er, but it does provide greater scope for creative development. For over 100 years, the Estonian Academy of Arts has served as the national leader in art and design, and through the work of its students and alumni has created the look of Estonia. In our current time of cross-cultural exchange, EAA seeks to share our specialised knowledge — from Blacksmithing to Animation to Urban Studies and more — with eager learners from beyond our borders. And we hope to likewise be enriched by the breadth of experiences and cultures that international students bring with them. www.artun.ee/masters One of EAA’s primary aims is to be an island of freedom in a world where those whose brains are limited by standard measures try to measure our immeasurable work. In a world ruled by Excel tables, as long as art manages to fulfi l its role as a centre of resistance there is still hope. -

Estonian-Art.Pdf

2_2014 1 News 3 The percentage act Raul Järg, Maria-Kristiina Soomre, Mari Emmus, Merike Estna, Ülle Luisk 6 I am a painting / Can't go on Discussion by Eha Komissarov, Maria-Kristiina Soomre, Marten Esko and Liina Siib 10 Long circuits for the pre-internet brain A correspondence between Niekolaas Johannes Lekkerkerk and Katja Novitskova 13 Post-internet art in the time of e-residency in Estonia Rebeka Põldsam 14 Platform: Experimenta! Tomaž Zupancˇicˇ 18 Total bass. Raul Keller’s exhibition What You Hear Is What You Get (Mostly) at EKKM Andrus Laansalu 21 Wild biscuits Jana Kukaine 24 Estonian Academy of Arts 100 Leonhard Lapin Insert: An education Laura Põld 27 When ambitions turned into caution Carl-Dag Lige 29 Picture in a museum. Nikolai Triik – symbol of hybrid Estonian modernism Tiina Abel 32 Notes from the capital of Estonian street art Aare Pilv 35 Not art, but the art of life Joonas Vangonen 38 From Balfron Tower to Crisis Point Aet Ader 41 Natural sciences and information technology in the service of art: the Rode altarpiece in close-up project Hilkka Hiiop and Hedi Kard 44 An Estonian designer without black bread? Kaarin Kivirähk 47 Rundum artist-run space and its elusive form Hanna Laura Kaljo, Mari-Leen Kiipli, Mari Volens, Kristina Õllek, Aap Tepper, Kulla Laas 50 Exhibitions 52 New books Estonian Art is included All issues of Estonian Art are also available on the Internet: http://www.estinst.ee/eng/estonian-art-eng/ in Art and Architecture Complete (EBSCO). Front cover: Kriss Soonik. Designer lingerie. -

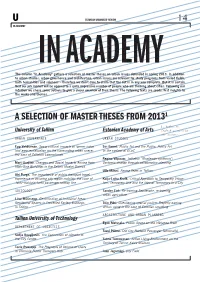

A Selection of Master Theses from 20131

ESTONIAN URBANISTS' REVIEW 14 IN ACADEMY IN ACADEMY The column "In Academy" gathers a selection of master theses on urban issues defended in spring 2013. In addition to urban studies, urban governance and architecture, urban issues are relevant for study programs from varied fields, both humanities and sciences – therefore we don't dare to claim that the list is in any way complete. But it is certain that our job market will be opened to a quite impressive number of people who are thinking about cities. Following our intuition we chose some authors to give a closer overview of their thesis. The following texts are seeds, first insights to the works and themes. A SELECTION OF MASTER THESES FROM 20131 1. titles in University of Tallinn Estonian Academy of Arts English as used by the authors. URBAN GOVERNANCE URBAN STUDIES Epp Vahtramäe. Socio-cultural impacts of former indus- Siri Emert. Public Art and the Public. Public Art trial area revitalization on the surrounding urban space: in the context of ECoC the case of Telliskivi Loomelinnak Regina Viljasaar. Initiative “Mustamäe synthesis”: Mart Uusjärv. Changes and Social Impacts Arising from Systemic change through collaborative planning High-Rise Buildings in the Tallinn Maakri District Ulla Männi. Facing Fears in Tallinn Airi Purge. The importance of public transport travel experience in assuring city region mobility: the case of Kaija-Luisa Kurik. Critical Approach to Temporary Urban- Tartu–Koidula–Tartu passenger railway line ism, Temporary Use and the Idea of Temporary in a City SOCIOLOGY Sander Tint. Re-framing Soodevahe, re-framing urban agriculture Liisa Müürsepp. -

Destination: Estonia

E S T Destination: O N Estonia I Relocation Guide A REPUBLIC OF ESTONIA CAPITAL Tallinn AREA 45,227 sq. km POPULATION 1,315,000 CURRENCY ONE SMALL NORDIC COUNTRY, Euro COUNTLESS REASONS TO FALL IN LOVE. 1. COUNTRY OVERVIEW 2. MOVING TO ESTONIA 6. EDUCATION 7. HEALTHCARE 4 Key Facts and Figures 16 Residence Permits 50 Pre-school Education 60 Health Insurance 7 Geography 21 Moving Pets 52 Basic Education 62 Family Physicians 8 Climate and Weather 22 Moving Your Car 54 Secondary Education 64 Specialised Medical Care 10 Population 56 Language Immersion Programmes 65 Dental Care CONTENTS 11 Language 56 Higher Education 66 Emergency Rooms and Hospitals 12 Religion 58 Continuous Education 13 Politics and Government 14 Public Holidays 14 Flag Days in Estonia 3. HOUSING 4. WORKING 5. TAXES AND BANKING 8. TRANSPORT 9. EVERYDAY LIFE 24 Renting Property 36 Work Permits 46 General Taxes 68 Driving in Estonia 84 e-Estonia 26 Buying and Selling Immovable Property 38 Employment Contracts 47 Income Tax 74 Your Car 86 Media 28 Utilities 40 Setting Up a Company 48 Everyday Banking 77 Parking 88 Shopping 31 Telecom Services 42 Finding a Job 78 Public Transport 90 Food 33 Postal Services 82 Taxis 91 Eating out 34 Moving Inside Estonia 92 Health and Beauty Services 35 Maintenance of Sidewalks 93 Sports and Leisure 94 Cultural Life 96 Travelling in Estonia On the cover: Reet Aus PhD, designer. Lives and works in Estonia. Photo by Madis Palm The Relocation Guide was written in cooperation with Talent Mobility Management www.talentmobility.ee 1. -

HIGHER EDUCATION in ESTONIA HIGHER EDUCATION in ESTONIA ARCHIMEDES FOUNDATION Estonian Academic Recognition Information Centre

HIGHER EDUCATION IN ESTONIA HIGHER EDUCATION IN ESTONIA ARCHIMEDES FOUNDATION Estonian Academic Recognition Information Centre HIGHER EDUCATION IN ESTONIA Fourth Edition TALLINN 2010 Compiled and edited by: Gunnar Vaht Liia Tüür Ülla Kulasalu With the support of the Lifelong Learning Programme/NARIC action of the European Union Cover design and layout: AS Ajakirjade Kirjastus ISBN 978-9949-9062-6-0 HIGHER EDUCATION IN ESTONIA PREFACE The current publication is the fourth edition of Higher Education in Es- tonia. The first edition was compiled in collaboration with the Estonian Ministry of Education in 1998, the second and the third (revised) edition appeared in 2001 and 2004 respectively. This edition has been considerably revised and updated to reflect the many changes that have taken place in the course of higher education reforms in general, and in the systems of higher education cycles and qualifications in particular, including the changes in the quality assess- ment procedures. The publication is an information tool for all those concerned with higher education in its international context. It contains information about the Estonian higher education system and the higher education institutions, meant primarily for use by credential evaluation and recognition bodies, such as recognition information centres, higher education institutions and employers. This information is necessary for a better understanding of Estonian qualifications and for their fair recognition in foreign countries. Taking into account the fact that credential evaluators and competent recogni- tion authorities in other countries will come across qualifications of the former systems, this book describes not only the current higher educa- tion system and the corresponding qualifications, but also the qualifica- tions of the former systems beginning with the Soviet period. -

Universities in Estonia

Universities in Estonia 1 Contents About Estonia 3 Estonian Academy of Arts (EKA) 4 Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre (EAMT) 6 Estonian Business School (EBS) 10 Estonian Entrepreneurship University of Applied Sciences (EUAS) 12 Estonian University of Life Sciences (EMÜ) 14 Tallinn Health Care College (THCC) 16 Tallinn University (TLU) 18 Tallinn University of Technology (TalTech) 20 Tartu Health Care College (THCC) 22 University of Tartu (UT) 24 Study in Estonia 26 Why Estonia? 27 2 About Estonia Estonia is quite a well-kept secret, Why Estonian universities? In this brochure we will highlight 10 still relatively unknown in many parts An innovative environment, combined universities in Estonia that offer degree of the world. Situated in Northern with great value for money, has made programmes taught fully in English. Europe, across the bay from Finland Estonia a desirable destination for and Sweden, we are a country of only both students and researchers in a For a list of all Estonian higher 1.3 million residents living on 45 000 knowledge-based society. education institutions visit: square kilometres. What we lack in hm.ee/en/activities/higher- numbers, however, we more than We offer high-quality degree programmes education make up for in spirit and big ideas! and internationally accepted diplomas. 91% of international students in Estonia Did you know? are happy with their studies at Esto- Estonia is: nian universities (Source: International 7000+ • the first country in the world to Student Barometer TM 2019). international students offer e-residency • the first country to adopt online Estonian scientists are successful voting participants in Horizon 2020 projects, 150+ • a digital society: less hassle means granting researchers almost twice degree programmes in time better spent the funding than other EU countries English • ranked 4th in the world based on on average. -

Eesti Kunstimuuseumi Toimetised Proceedings of the Art Museum of Estonia

4 [9] 2014 EESTI KUNSTIMUUSEUMI TOIMETISED PROCEEDINGS OF THE ART MUSEUM OF ESTONIA 4 [9] 2014 Naiskunstnik ja tema aeg A Woman Artist and Her Time 4 [9] 2014 EESTI KUNSTIMUUSEUMI TOIMETISED PROCEEDINGS OF THE ART MUSEUM OF ESTONIA Naiskunstnik ja tema aeg A Woman Artist and Her Time TALLINN 2014 Esikaanel: Lydia Mei (1896−1965). Natalie Mei portree. 1930. Akvarell. Eesti Kunstimuuseum On the cover: Lydia Mei (1896−1965). Portrait of Natalie Mei. 1930. Watercolour. Art Museum of Estonia Ajakirjas avaldatud artiklid on eelretsenseeritud. All articles published in the journal were peer-reviewed. Toimetuskolleegium / Editorial Board: Kristiāna Ābele, PhD (Läti Kunstiakadeemia Kunstiajaloo Instituut, Riia / Institute of Art History of Latvian Academy of Art, Riga) Natalja Bartels, PhD (Venemaa Kunstide Akadeemia Kunstiajaloo ja -teooria Instituut, Moskva / Research Institute of Theory and History of Arts of the Russian Academy of Arts, Moscow) Dorothee von Hellermann, PhD (Oxford) Irmeli Hautamäki, PhD (Helsingi Ülikool ja Jyväskylä Ülikool / University of Helsinki and University of Jyväskylä) Sirje Helme, PhD (Eesti Kunstimuuseum, Tallinn / Art Museum of Estonia, Tallinn) Ljudmila Markina, PhD (Riiklik Tretjakovi Galerii, Moskva / State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) Piotr Piotrovski, PhD (Adam Mickiewiczi Ülikool, Poznan / Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan) Kadi Polli, MA (Tartu Ülikool / University of Tartu) Peatoimetaja / Editor-in-chief: Merike Kurisoo Koostaja / Compiler: Kersti Koll Toimetajad / Editors: Kersti Koll, Merike Kurisoo Keeletoimetaja