Vice Admiral Marmaduke G. Bayne US Navy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED STATES SUBMARINE VETERANS INCORPORTATED PALMETTO BASE NEWSLETTER December 2011

OUR CREED: To perpetuate the memory of our shipmates who gave their lives in the pursuit of duties while serving their country. That their dedication, deeds, and supreme sacrifice be a constant source of motivation toward greater accomplishments. Pledge loyalty and patriotism to the United States of America and its constitution. UNITED STATES SUBMARINE VETERANS INCORPORTATED PALMETTO BASE NEWSLETTER December 2011 1 Picture of the Month………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...3 Members…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Honorary Members……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 Meeting Attendees………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..….5 Old Business….…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 New Business…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Good of the Order……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..6 Base Contacts…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8 Birthdays……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Welcome…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 Binnacle List……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………,…8 Quote of the Month.……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…8 Fernando Igleasis Eternal Patrol…………………………………………………………………………………………………9 Robert Gibbs’ Memorial……………..….…………………..……………………………………………………………………10 Lexington Veteran’s Day Parade………………………………………………………………………………………………12 Columbia Veteran’s Day Parade.………………………………………………………………………………………………13 Dates in American Naval History………………………………………………………………………………………………16 Dates in U.S. Submarine History………………………………………………………………………………………………22 -

Adobe PDF File

BOOK REVIEWS Lewis R. Fischer, Harald Hamre, Poul that by Nicholas Rodger on "Shipboard Life Holm, Jaap R. Bruijn (eds.). The North Sea: in the Georgian Navy," has very little to do Twelve Essays on Social History of Maritime with the North Sea and the same remark Labour. Stavanger: Stavanger Maritime applies to Paul van Royen's essay on "Re• Museum, 1992.216 pp., illustrations, figures, cruitment Patterns of the Dutch Merchant photographs, tables. NOK 150 + postage & Marine in the Seventeenth to Nineteenth packing, cloth; ISBN 82-90054-34-3. Centuries." On the other hand, Professor Lewis Fischer's "Around the Rim: Seamens' This book comprises the papers delivered at Wages in North Sea Ports, 1863-1900," a conference held at Stavanger, Norway, in James Coull's "Seasonal Fisheries Migration: August 1989. This was the third North Sea The Case of the Migration from Scotland to conference organised by the Stavanger the East Anglian Autumn Herring Fishery" Maritime Museum. The first was held at the and four other papers dealing with different Utstein Monastery in Stavanger Fjord in aspects of fishing industries are directly June 1978, and the second in Sandbjerg related to the conferences' central themes. Castle, Denmark in October 1979. The pro• One of the most interesting of these is Joan ceedings of these meetings were published Pauli Joensen's paper on the Faroe fishery in one volume by the Norwegian University in the age of the handline smack—a study Press, Oslo, in 1985 in identical format to which describes an age of transition in the volume under review, under the title The social, economic and technical terms. -

Volume 2018 $6.00

Volume 2018 1st Quarter American $6.00 Submariner Less we forget USS Scorpion SSN-589. She and our shipmates entered Eternal Patrol on May 22, 1968. There will be more coverage in Volume 2, later this year. Download your American Submariner Electronically - Same great magazine, available earlier. Send an E-mail to [email protected] requesting the change. ISBN LIST 978-0-9896015-0-4 AMERICAN SUBMARINER Page 2 - American Submariner Volume 2018 - Issue 1 Page 3 AMERICAN Table of Contents SUBMARINER Page Number Article This Official Magazine of the United 3 Table of Contents, Deadlines for Submission States Submarine Veterans Inc. is published quarterly by USSVI. 4 USSVI National Officers United States Submarine Veterans Inc. 5 “Poopie Suits & Cowboy Boots” – book proceeds all to charity is a non-profit 501 (C) (19) corporation 6 Selected USSVI . Contacts and Committees in the State of Connecticut. 6 Veterans Affairs Service Officer Printing and Mailing: A. J. Bart of Dallas, Texas. 8 USSVI Regions and Districts 9 USSVI Purpose National Editor 9 A Message from the Chaplain Chuck Emmett 10 Boat Reunions 7011 W. Risner Rd. 11 “How I See It” – message from the editor Glendale, AZ 85308 12 Letters-to-the-Editor (623) 455-8999 15 “Lest We Forget” – shipmates departed on Eternal Patrol [email protected] 20-21 Centerfold – 2018 Cruise/Convention Assistant Editor 22 New USSVI Members Bob Farris 24-25 Boat Sponsorship Program (BSP) (315) 529-97561 27 “From Sea-to-Shining-Sea” – Base Information [email protected], 28 Forever on Eternal Patrol – boats that shall never return 30 7Assoc. -

Andrew Dorman Michael D. Kandiah and Gillian Staerck ICBH Witness

edited by Andrew Dorman Michael D. Kandiah and Gillian Staerck ICBH Witness Seminar Programme The Nott Review The ICBH is grateful to the Ministry of Defence for help with the costs of producing and editing this seminar for publication The analysis, opinions and conclusions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the JSCSC, the UK Ministry of Defence, any other Government agency or the ICBH. ICBH Witness Seminar Programme Programme Director: Dr Michael D. Kandiah © Institute of Contemporary British History, 2002 All rights reserved. This material is made available for use for personal research and study. We give per- mission for the entire files to be downloaded to your computer for such personal use only. For reproduction or further distribution of all or part of the file (except as constitutes fair dealing), permission must be sought from ICBH. Published by Institute of Contemporary British History Institute of Historical Research School of Advanced Study University of London Malet St London WC1E 7HU ISBN: 1 871348 72 2 The Nott Review (Cmnd 8288, The UK Defence Programme: The Way Forward) Held 20 June 2001, 2 p.m. – 6 p.m. Joint Services Command and Staff College Watchfield (near Swindon), Wiltshire Chaired by Geoffrey Till Paper by Andrew Dorman Seminar edited by Andrew Dorman, Michael D. Kandiah and Gillian Staerck Seminar organised by ICBH in conjunction with Defence Studies, King’s College London, and the Joint Service Command and Staff College, Ministry of -

The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander Free

FREE ONE HUNDRED DAYS: THE MEMOIRS OF THE FALKLANDS BATTLE GROUP COMMANDER PDF Sandy Woodward,Patrick Robinson | 576 pages | 29 Mar 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007436408 | English | London, United Kingdom One hundred days - Sandy Woodward At times reflective and personal, Woodward imparts his perceptions, fears, and reactions to seemingly disastrous events. He also reveals the steely logic he was famous for as he explains naval strategy and planning. Many Britons considered Woodward the cleverest man in the navy. French newspapers called him "Nelson. Without question, the admiral's memoir makes a significant addition to the official record. At the same time it provides readers with a vivid portrayal of the world of modern naval warfare, where equipment is of astonishing sophistication but the margins for human courage and error are as wide as in the days of Nelson. The Falkland Islands War of was remarkable in many respects. At the outset of the Thatcher-Reagan era, the conflict strengthened the resolve of the One Hundred Days: The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander to bolster rather than reduce the size This book gives an incredible insight into the mind of a naval task force leader at war. His decision making process, while on the surface seems cold and heartless, actually makes sense when he Patrick Robinson was a journalist for many years One Hundred Days: The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander becoming a full-time writer of books. His non-fiction books were bestsellers around the world and he was the co-author of Sandy Woodward's Falklands War memoir, One Hundred Days. -

Battle Atlas of the Falklands War 1982

ACLARACION DE www.radarmalvinas.com.ar El presente escrito en PDF es transcripción de la versión para internet del libro BATTLE ATLAS OF THE FALKLANDS WAR 1982 by Land, Sea, and Air de GORDON SMITH, publicado por Ian Allan en 1989, y revisado en 2006 Usted puede acceder al mismo en el sitio www.naval-history.com Ha sido transcripto a PDF y colocado en el sitio del radar Malvinas al sólo efecto de preservarlo como documento histórico y asegurar su acceso en caso de que su archivo o su sitio no continúen en internet, ya que la información que contiene sobre los desplazamientos de los medios británicos y su cronología resultan sumamente útiles como información británica a confrontar al analizar lo expresado en los diferentes informes argentinos. A efectos de preservar los derechos de edición, se puede bajar y guardar para leerlo en pantalla como si fuera un libro prestado por una biblioteca, pero no se puede copiar, editar o imprimir. Copyright © Penarth: Naval–History.Net, 2006, International Journal of Naval History, 2008 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- BATTLE ATLAS OF THE FALKLANDS WAR 1982 NAVAL-HISTORY.NET GORDON SMITH BATTLE ATLAS of the FALKLANDS WAR 1982 by Land, Sea and Air by Gordon Smith HMS Plymouth, frigate (Courtesy MOD (Navy) PAG Introduction & Original Introduction & Note to 006 Based Notes Internet Page on the Reading notes & abbreviations 008 book People, places, events, forces 012 by Gordon Smith, Argentine 1. Falkland Islands 021 Invasion and British 2. Argentina 022 published by Ian Allan 1989 Response 3. History of Falklands dispute 023 4. South Georgia invasion 025 5. -

Under Fire: the Falklands War and the Revival of Naval Gunfire Support

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Portsmouth University Research Portal (Pure) Steven Paget Published in War in History, 24:2, 2017, pp.217-235. This is the post-print version and must not be copied or cited without permission. Under Fire: The Falklands War and the Revival of Naval Gunfire Support I have always placed a high priority on exercising NGS. All my ships have had the capacity & I made sure we knew how to use it. NGS became a lower priority for the Naval Staff & new construction planned had no gun. Op [Operation] Corporate changed all that thinking. Captain Michael Barrow1 The reputation of naval gunfire support (NGS) has waxed and waned since the initial development of the capability. At times, NGS has been considered to have been of supreme importance. At others, it has been viewed as worthless. By the end of the 1970s, there was burgeoning opinion in some circles that NGS had become obsolete. Operation Corporate – the Falklands War – demonstrated that reports of the demise of NGS had been greatly exaggerated. NGS played a prominent role during Operation Corporate, but it was just one of a multitude of capabilities. As John Ballard put it: ‘The British...integrated nearly every tool in the kit bag to mount their operation rapidly and win at the knife’s edge of culmination.’2 There can be no doubt that the destructive mix of capabilities utilised by British forces was crucial to the success of Operation Corporate. However, due to the inevitable limits of operating so far from home, NGS was often required to redress deficiencies in other fire support capabilities. -

Vice Admiral Marmaduke G. Bayne US Navy

Oral History Vice Admiral Marmaduke G. Bayne U.S. Navy (Retired) Conducted by David F. Winkler, Ph.D. Naval Historical Foundation 16 July 1998 26 August 1998 Naval Historical Foundation Washington, DC 2000 Introduction I first contacted Vice Admiral Bayne in 1996, it was in relation to another series of interviews I had intended to conduct with Secretary of the Navy Fred Korth. Bayne had served as Korth’s Executive Assistant and thus could provide an overview of the issues. He invited me to Irvington and was gracious with his time, providing me with good background material. At that time it became obvious that Bayne would be a good interview subject, however, he politely declined. Unfortunately, Korth fell ill and subsequently passed away so the planned interviews were never conducted. However, Bayne had a change of heart and agreed to a biographical interview that included the period that he served as Korth’s EA. Besides serving as a SecNav EA, Vice Admiral Bayne’s career is significant as he served in the Submarine Service during a period of transformation from WWII diesel boats to a force including nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines. In his interviews, Bayne details a career serving as a junior officer on a Fleet Boat in the Western Pacific battling the Japanese Empire to command of a missile boat flotilla in the Mediterranean Sea in the late 1960s. In addition, he served in several political-military posts, with his most important being Commander, Middle East Force. As COMIDEASTFOR, Bayne negotiated with the Bahraini government for an American naval shore presence there that continues to the present. -

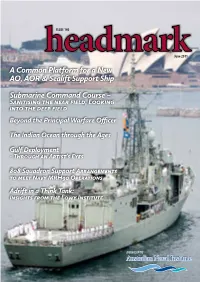

A Common Platform for a New AO, AOR

ISSUE 140 June 2011 A Common Platform for a New AO, AOR & Sealift Support Ship Submarine Command Course – Sanitising the near field, Looking into the deep field Beyond the Principal Warfare Officer The Indian Ocean through the Ages Gulf Deployment - Through an Artist’s Eyes 808 Squadron Support Arrangements to meet Navy MRH90 Operations Adrift in a Think Tank: Insights from the Lowy Institute JOURNAL OF THE Issue 140 3 Letters to the Editor Contents Dear Editor, As a member of the Naval Historical I enjoyed the article in Issue 138 Advisory Committee responsible for A Common Platform for a New AO, December 2010 by Midshipman overseeing the selection process for the AOR & Sealift Support Ship 4 Claire Hodge on RAN Helicopter names of future RAN ships I was very Flight Vietnam but must correct her interested to read the article written by Submarine Command Course – Note 2, where she states that SEA LCDR Paul Garai, RAN, which appears Sanitising the near field, Looking into DRAGON was the RAN’s principal in Headmark Issue 138, concerning the deep field 7 commitment during the Vietnam war, giving more meaningful names to the and the ships involved were HMA two new LHD’s. Beyond the Principal Warfare Officer 13 Ships Hobart, Vendetta and Brisbane. When viewing the article I was SEA DRAGON was the surprised to read that the RAN The Indian Ocean through the Ages 20 interdiction of supply routes and had previously named a destroyer logistic craft along the coast of North Gallipoli. This is a misleading Studies in Trait Leadership – Loved Vietnam from the DMZ to the Red comment. -

Falklands Royal Navy Wives: Fulfilling a Militarised Stereotype Or Articulating Individuality?

Falklands Royal Navy Wives: fulfilling a militarised stereotype or articulating individuality? Victoria Mary Woodman The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. December 2018 Abstract ‘Falklands Royal Navy Wives: fulfilling a militarised stereotype or articulating individuality?’ Key words: Falklands War/1980s/naval wives/oral history/remembrance/commemoration/gendered conflict/media/naval welfare/PTSD This thesis demonstrates that Falklands naval wives were not the homogeneous and stereotypical group portrayed in the media, but individuals experiencing specific effects of conflict on combatants, wives and families. It contributes originally to oral history by exploring retrospective memories of Falkland’s naval wives and their value to wider history. Falklands naval wives as individuals had not been researched before. The conflict was fought in the media using gendered and paternalistic language and images, a binary of man fighting versus woman serving the home front. The aim is to widen the scope of the gender, social, naval and cultural history of the Falklands Conflict by recording naval wives’ views before they were lost, thereby offering new insight into the history of the Falklands Conflict. Original research described in this thesis addresses several important research questions: 1. If a group of naval wives underwent the same events, would their views/thoughts/ experiences be comparable? 2. Was the image depicted in existing literature the only view? 3. Did the naval community differ from the rest of society; how were its gender roles defined? 4. Did the wives’ thoughts and feelings differ from those reported in the press? 5. -

The 2014 Newsletter

2014 Judy Barrow and her family with Rear Admiral Hugh Edleston and HMS Glamorgan Standard Bearer Eon Matthews CHAIRMAN’S LETTER It is unprecedented that a Chapel these special circumstances Trustees so pleased that the Chapel means so On Saturday June 15th HMS Hermes Trust Chairman has had to write of Rev. David Cooper and Anthony much to so many. We were pleased too Association gathered together in the the sad passing of two amongst us Hudson describe their thoughts and to be able to carry out the presentation Chapel for a special service to lay during the past year. I refer, of course, memories for you on pages 4 and 5. of more Elizabeth Crosses to Next of their Falklands Memorial Stone at to Captain Michael Barrow CVO Kin discovered by the enduring efforts the Cairn. (page 6). We are so very DSO RN – Founder Trustee and a The Annual Service on 16th June last of the FFA’s Treasurer and bereaved grateful to Reverend Neil Jeffers former Chairman- and Admiral Sir year was clearly another memorable father Ray Poole (page 7). To date, for organising and conducting this John ‘Sandy’ Woodward GBE KCB occasion (pages 2 & 3) although I had 40 families have been able to receive Service together with the Annual – Founder Chairman and latterly our been called away overseas. I remain their medals in the Chapel and many Service and other ‘special’ services President – two great men to whom hugely grateful to my ‘deputies’ Major more by other means through his and throughout the year in addition to his we owe an enormous debt of gratitude. -

Emce Thesis FINAL LIBRARY 03082014

PROFESSIONAL READING AND THE EDUCATION OF MILITARY LEADERS By Emmet James McElhatton A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Policy Victoria University of Wellington 2014 1 ABSTRACT Prominent military figures, both contemporary and historical have, through both personal example and their promotion of critical literacy initiatives, emphasised the role of professional reading in the development of the professional wisdom that underpins effective military leadership. While biographical studies hint at a connection between the extracurricular reading habits of notable military figures and the development of their professional wisdom, the majority of studies on military leadership development focus either through the context of experience or on development through the medium of formal educational programmes. Considering the time and resources invested in formal educational programmes, and the highly incremental nature of self-development that makes its utility difficult to measure, it is understandable but not acceptable that continuous, career-long self- development through professional reading receives scant attention. Using a hermeneutically derived conceptual framework as an analytical tool, this research explores the intellectual component of military leadership, as embodied in the idea of the warrior-scholar, and the role the phenomena of reading, text, and canon, play in the development of the cognitive skills – critical, creative, and strategic thinking – necessary for successful leadership in complex institutions and environments. The research seeks to contribute original insights into the role that professional reading actually plays in the intellectual development of military leaders. The research also seeks to determine the extent to which a military canon that embodies professional military wisdom exists, and the relationship that this canon might have on the development of military leaders in the contemporary environment.