The City – Psychogeography in Brisbane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oxford Street

Oxford Street The Bulimba District, Brisbane, Australia Project Type: Mixed-Use/Multi-Use Case No: C033007 Year: 2003 SUMMARY A public/private partnership to transform a defunct shopping strip located in the Bulimba District of Brisbane, Australia, into a vibrant, mixed-use district. The catalyst for this transformation is a city-sponsored program to renovate and improve the street and sidewalks along the 0.6-mile (one-kilometer) retail strip of Oxford Street. FEATURES Public/private partnership City-sponsored improvements program Streetscape redevelopment Oxford Street The Bulimba District, Brisbane, Australia Project Type: Mixed-Use/Multi-Use Volume 33 Number 07 April–June 2003 Case Number: C033007 PROJECT TYPE A public/private partnership to transform a defunct shopping strip located in the Bulimba District of Brisbane, Australia, into a vibrant, mixed-use district. The catalyst for this transformation is a city-sponsored program to renovate and improve the street and sidewalks along the 0.6-mile (one-kilometer) retail strip of Oxford Street. SPECIAL FEATURES Public/private partnership City-sponsored improvements program Streetscape redevelopment PROGRAM MANAGER Brisbane City Council Brisbane Administration Center 69 Ann Street Brisbane 4000 Queensland Australia Postal Address GPO Box 1434 Brisbane 4001 Queensland Australia (07) 3403 8888 Fax: (07) 3403 9944 www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/ council_at_work/improving_city/ creating_living_villages/ suburban_centre/index.shtml GENERAL DESCRIPTION Over the past ten years, Oxford Street, located in the Bulimba District of Brisbane, Australia, has been transformed from a defunct shopping strip into a vibrant, mixed-use district. The catalyst for this turnaround is a public/private partnership between Brisbane’s city council and Oxford Street’s local business owners. -

Property Report

PROPERTY REPORT Queensland Softer residential National overview property prices around the country are presenting In this edition of the Westpac Herron Todd White Residential opportunities for Property Report, we are putting the spotlight on the aspiring landlords opportunities for cashed-up investors and self-managed super and DIY superfunds, funds (SMSFs). and we’ll take a look Softer residential property prices around the country are at some of the stand- presenting opportunities for aspiring landlords and DIY out investment real superfunds, and we’ll take a look at some of the stand-out estate markets. investment real estate markets. A buyer’s market With lending still tight and confidence relatively low, competition for quality homes is comparatively thin on the ground, particularly in the entry level markets that are typically popular with investors. While prices are yet to hit bargain basement levels, it’s fair to say they have flattened out. This is good news for cashed-up investors and SMSFs looking for long-term capital gains. Leading the way is the Western Australian market, which has stabilised after a booming period of growth. Similarly, there has been a slight drop in Tasmanian real estate values after 10 years of strong returns. Indeed some markets in and around Hobart, such as Sandy Bay, South Hobart and West Hobart, recorded growth of more than 200% over the last decade. Property a long term investment While buyers, particularly first timers, might be taking a wait-and-see approach, rental markets around Australia are still relatively strong. As a result, vacancy rates are low and this is keeping rents steady, which is good news for investor cash flow. -

Safer School Travel for Runcorn Discover the Urban Stories of Artist Robert Brownhall WHAT's ON

Safer school travel for Runcorn Students at Runcorn Heights State Primary School have received a school travel safety boost after Council completed works as part of the Safe School Travel program. The school has a high percentage of students who walk, cycle, carpool and catch public transport to school. Council recently installed pedestrian safety islands at the school crossing on Nemies Road to improve safety for students and their parents and guardians.The final design of the improvement was decided after consultation with both the school and residents in the area and was delivered with the Queensland Government’s Department of Transport and Main Roads. Council’s Safe School Travel program has operated since 1991 to improve safety across Brisbane’s road network, including children’s daily commute to and from school. The Safe School Travel program delivers about 12 improvement projects each year. Robert Brownhall Story Bridge at Dusk (detail) 2010, City of Brisbane Collection, Museum of Brisbane. WHAT’S ON 7-12 April: Festival of German Films, Palace Centro, Fortitude Valley. 11 & 13 April: Jazzercise (Growing Older and Living Dangerously), 6.30-7.30pm, Calamvale Community College, Calamvale. 15-17 April: Gardening Discover the urban stories of Australia Expo 2011, Brisbane Convention and Exhibition artist Robert Brownhall Centre, www.abcgardening expo.com.au. Get along to Museum of Brisbane from 15 April to experience Brisbane through the eyes of Robert Brownhall. 16-26 April: 21st Century Kids Festival, Gallery of Modern Art, Somewhere in the City: Urban narratives by Robert Brownhall will showcase South Bank, FREE. Brownhall’s quirky style and birds-eye view of Brisbane. -

Department of Government and Political Science Submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts 12 December 1968

A STUDY OF THE PORIIATION OF THE BRISBANE T01\rN PLAN David N, Cox, B.A. Department of Government and Political Science Submitted for the degree of Master of Arts 12 December 1968 CHAPTER I TOWN PLANNING IN BRISBANE TO 1953 The first orderly plans for the City of Brisbane were in the form of an 1840 suirvey preceding the sale of allotments to the public. The original surveyor was Robert Dixon, but he was replaced by Henry Wade in 1843• Wade proposed principal streets ihO links (92,4 ft.) in width, allotments of ^ acre to allow for air space and gardens, public squares, and reserves and roads along 2 the river banks. A visit to the proposed village by the New South Wales Colonial Governor, Sir George Gipps, had infelicitous results. To Gipps, "It was utterly absurd, to lay out a design for a great city in a place which in the very 3 nature of things could never be more than a village." 1 Robinson, R.H., For My Country, Brisbane: W, R. Smith and Paterson Pty. Ltd., 1957, pp. 23-28. 2 Mellor, E.D., "The Changing Face of Brisbane", Journal of the Royal Historical Society. Vol. VI., No. 2, 1959- 1960, pp. 35^-355. 3 Adelaide Town Planning Conference and Exliibition, Official Volume of Proceedings, Adelaide: Vardon and Sons, Ltd., I9I8, p. 119. He went further to say that "open spaces shown on the pleua were highly undesirable, since they might prove an inducement to disaffected persons to assemble k tumultuously to the detriment of His Majesty's peace." The Governor thus eliminated the reserves and river 5 front plans and reduced allotments to 5 to the acre. -

Pdf, 522.77 KB

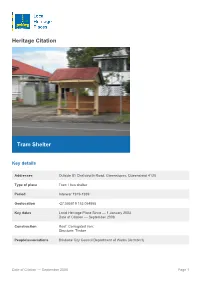

Heritage Citation Tram Shelter Key details Addresses Outside 81 Chatsworth Road, Greenslopes, Queensland 4120 Type of place Tram / bus shelter Period Interwar 1919-1939 Geolocation -27.505819 153.054955 Key dates Local Heritage Place Since — 1 January 2003 Date of Citation — September 2008 Construction Roof: Corrugated iron; Structure: Timber People/associations Brisbane City Council Department of Works (Architect) Date of Citation — September 2008 Page 1 Criterion for listing (A) Historical; (B) Rarity This two-posted double-sided timber tram shelter was constructed by the Brisbane City Council around the 1930s and was originally the terminus of the electric tram route along Chatsworth Road. The shelter is significant for the evidence it provides of Brisbane’s tramway system and for its contribution to the streetscape of Chatsworth Road. History This timber tram shelter is typical of those constructed by the Brisbane City Council on the city’s tram routes during the 1930s. Although it is situated on a tramline constructed in 1914, tram shelters were not generally built during this period, but appeared later as part of the Brisbane City Council’s efforts to improve the tramway system. Brisbane’s association with trams began in August 1885 with the horse tram, owned by the Metropolitan Tramway & Investment Co. In 1895, a contract was let to the Tramways Construction Co. Ltd. of London to electrify the system. The new electric tramway system officially opened on 21 June 1897 when a tram ran from Logan Road to the Victoria Bridge. Other lines opened in that year included the George Street, Red Hill and Paddington lines. -

Pdf, 504.76 KB

Heritage Information Please contact us for more information about this place: [email protected] -OR- phone 07 3403 8888 Hooper's shop (former) Date of Information — August 2006 Page 1 Key details Addresses At 138 Wickham Street, Fortitude Valley, Queensland 4006 Type of place Shop/s Period Interwar 1919-1939 Style Anglo-Dutch Lot plan L3_RP9471 Key dates Local Heritage Place Since — 30 October 2000 Date of Information — August 2006 Construction Walls: Masonry - Render People/associations Chambers and Ford (Architect) Criterion for listing (A) Historical; (E) Aesthetic; (H) Historical association This single storey rendered brick building, designed by notable architects Chambers and Ford, is influenced by the Federation Anglo-Dutch style. It was built in 1922 for jeweller and optometrist George Hooper, who opened a jewellery store that operated until around 1950. It is one of a row of buildings in Wickham Street that form a harmonious streetscape and demonstrate the renewal and growth that occurred in Fortitude Valley in the 1920s. History The Paddy Pallin building is a single storey commercial building designed by Brisbane architects, Chambers and Ford, for owner George Hooper, jeweller and optometrist, who purchased the 6 and 21/100 perch site in July 1922 after subdivision of a larger pre-existing block. This building and others in the block were constructed in the 1920s, replacing earlier buildings, some of which were timber and iron. The 1920s was a decade of economic growth throughout Brisbane. The Valley in particular, with its success as a commercial and industrial hub, expanded even further. Electric trams, which passed the busy corner of Brunswick and Wickham Streets, brought thousands of shoppers to the Valley. -

The Death and Life of Great Australian Music: Planning for Live Music Venues in Australian Cities

The Death and Life of Great Australian Music: planning for live music venues in Australian Cities The Death and Life of Great Australian Music: planning for live music venues in Australian Cities Dr Matthew Burke1 Amy Schmidt2 1Urban Research Program Griffith University 170 Kessels Road Nathan Qld 4111 Australia [email protected] 2Craven Ovenden Town Planning Brisbane, Australia [email protected] Word count: 4,854 words excluding abstract and references Running header: The Death and Life of Great Australian Music Key words: live music, noise, urban planning, entertainment precincts Abstract In recent decades outdated noise, planning and liquor laws, encroaching residential development, and the rise of more lucrative forms of entertainment for venue operators, such as poker machines, have acted singly or in combination to close many live music venues in Australia. A set of diverse and quite unique policy and planning initiatives have emerged across Australia’s cities responding to these threats. This paper provides the results of a systematic research effort conducted in 2008 into the success or otherwise of these approaches in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne. Archival and legislative reviews and field visits were supplemented by interviews with key authorities, venue operators, live music campaigners and others in each city. The research sought to categorise and evaluate the diverse approaches being used and to attempt to understand best ways forward to maintain opportunities for live music performance. In Brisbane a place-based approach designating ‘Entertainment Precincts’ has been used, re-writing separate pieces of legislation (across planning, noise and liquor law). Resulting in monopolies for the few venue operators within the precincts, outside the threats remain and venues continue to be lost. -

Aboriginal Camps As Urban Foundations? Evidence from Southern Queensland Ray Kerkhove

Aboriginal camps as urban foundations? Evidence from southern Queensland Ray Kerkhove Musgrave Park: Aboriginal Brisbane’s political heartland In 1982, Musgrave Park in South Brisbane took centre stage in Queensland’s ‘State of Emergency’ protests. Bob Weatherall, President of FAIRA (Foundation for Aboriginal and Islanders Research Action), together with Neville Bonner – Australia’s first Aboriginal Senator – proclaimed it ‘Aboriginal land’. Musgrave Park could hardly be more central to the issue of land rights. It lies in inner Brisbane – just across the river from the government agencies that were at the time trying to quash Aboriginal appeals for landownership, yet within the state’s cultural hub, the South Bank Precinct. It was a very contentious green space. Written and oral sources concur that the park had been an Aboriginal networking venue since the 1940s.1 OPAL (One People of Australia League) House – Queensland’s first Aboriginal-focused organisation – was established close to the park in 1961 specifically to service the large number of Aboriginal people already using it. Soon after, many key Brisbane Aboriginal services sprang up around the park’s peripheries. By 1971, the Black Panther party emerged with a dramatic march into central Brisbane.2 More recently, Musgrave Park served as Queensland’s ‘tent 1 Aird 2001; Romano 2008. 2 Lothian 2007: 21. 141 ABORIGINAL HISTORY VOL 42 2018 embassy’ and tent city for a series of protests (1988, 2012 and 2014).3 It attracts 20,000 people to its annual NAIDOC (National Aboriginal and Islander Day Observance Committee) Week, Australia’s largest-attended NAIDOC venue.4 This history makes Musgrave Park the unofficial political capital of Aboriginal Brisbane. -

Legislative Assembly Hansard 1967

Queensland Parliamentary Debates [Hansard] Legislative Assembly TUESDAY, 21 FEBRUARY 1967 Electronic reproduction of original hardcopy QUEENSLAND Parliamentary Debates (HANSARD) FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT (Second Period) TUESDAY, 21 FEBRUARY, 1967 Gas Act Amendment Bill. Public Service Superannuation Acts Amend ment Bill. Under the provisions of the motion for Agricultural Chemicals Distribution special adjournment agreed to by the House Control Bill. on 7 December, 1966, the House met at 11 a.m. Local Government Acts Amendment Bill. City of Brisbane Acts Amendment Bill. Mr. SPEAKER (Hon. D. E. Nicholson, Murrumba) read prayers and took the chair. Marketable Securities Bill. ASSENT TO BILLS QUEENSLAND MARINE ACTS AMENDMENT BILL Assent to the following Bills reported by Mr. Speaker- RESERVATION FOR ROYAL ASSENT Weights and Measures Acts Amendment Mr. SPEAKER reported receipt of a BilL message from His Excellency the Governor Fire Brigades Acts Amendment Bill. intimating that this Bill had been reserved Land Tax Acts Amendment Bill. for the signification of Her Majesty's pleasure. Stamp Acts and Another Act Amendment QUESTION Bill. PARKING OF VEHICLES IN CAIRNS Door to Door (Sales) Bill. Mr. R. Jones, pursuant to notice, asked The Primary Producers' Organisation and Minister for Mines, Marketing Acts Amendment Bill. In view of widespread concern and Regulation of Sugar Cane Prices Acts inconvenience caused by parallel parking in Amendment Bill. the wide streets of Cairns, will he provide Inspection of Machinery Acts and Another angle-parking and where angle-parking is Act Amendment Bill. not practicable have signs erected to denote the areas excepted from such Police (Photographs) Bill. -

Enhance Your Degree with Study Abroad Or Incoming Exchange

Enhance your degree with Study Abroad or Incoming Exchange UQ Guide 2021 Important dates 2021 JANUARY 1 January New Year’s Day 26 January Australia Day holiday FEBRUARY 15–19 February Orientation Week Contents 22 February Semester 1 starts 28 February Semester 2 application closing date for Incoming Exchange Welcome to UQ 1 MARCH 31 March Census date (Semester 1) 31 March Semester 2 application closing date for Choose UQ 2 Study Abroad APRIL 2 April Good Friday 5 April Easter Monday Our global reputation 4 5–11 April Mid-semester break 12 April Semester 1 resumes The perfect place to study 6 25 April ANZAC Day holiday A welcome as warm MAY 3 May Labour Day holiday 31 May–4 June Revision period as the weather 8 JUNE 5–19 June Examination period UQ St Lucia 10 19 June Semester 1 ends UQ Gatton 11 19 June–25 July Mid-year break UQ Herston 11 JULY 19–23 July Mid-year Orientation Week 26 July Semester 2 starts UQ study options 12 Find a UQ course 17 AUGUST 9 August Royal Queensland Show holiday (Gatton) 11 August Royal Queensland Show holiday (St Lucia and Herston) Explore Queensland: 31 August Census date (Semester 2) courses with field trips 18 SEPTEMBER 27 September–4 October Mid-semester break 30 September Semester 1 application closing date for Student support 20 Incoming Exchange OCTOBER 4 October Queen’s Birthday holiday Accommodation 24 5 October Semester 2 resumes 31 October Semester 1 application closing date for Study Abroad Cost of living 26 NOVEMBER 1–5 November Revision period 6–20 November Examination period Fees and expenses 27 20 November Semester 2 ends DECEMBER 27 December Christmas Day holiday 28 December Boxing Day holiday Are you eligible? 28 These dates are subject to change – please check the Academic Calendar at How to apply 29 uq.edu.au/events for up-to-date information Disclaimer ESOS compliance CRICOS Provider 00025B The information in this Guide is accurate at July The provision of education services to international ESOS Act 2020. -

Inner-Urban Sustainability: a Case Study of the South Brisbane Peninsula

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queensland University of Technology ePrints Archive INNER-URBAN SUSTAINABILITY: A CASE STUDY OF THE SOUTH BRISBANE PENINSULA 1 D.J. O’Hare Abstract The combination of elements and conditions in inner-urban areas may be argued to constitute established patterns of urban sustainability. This paper develops the argument through a case study of the South Brisbane peninsula, one of Queensland’s oldest and densest inner-urban areas. For the purposes of the paper, urban sustainability is defined in the context of urban design and development. This definition highlights the interrelationship between urban form and structure, and the social and economic life of the city. The paper argues that South Brisbane demonstrates significant characteristics of ‘triple bottom line’ environmental, social and economic sustainability in a subtropical inner-urban context. The main data source is a major study of Queensland’s cultural landscapes, supplemented by analysis and interpretation of current local government planning and community advocacy for sustainability. The area is strongly supportive of sustainability in terms of residential densities; mixed land uses; coherent urban structure, with strong local centres serviceable by public transport; mixed building types and ages; diversity in culture and socioeconomic status of the population; and social capital in the form of engaged and creative communities. The management of such diverse and dynamic inner-urban areas raises challenges for sustainable urban design and development practice. Keywords: West End, Brisbane, social capital, urban design, urban sustainability. 1. Introduction South Brisbane ‘peninsula’ is bounded by the Brisbane River immediately south of the Brisbane city centre. -

12. Cultural Heritage

12. Cultural Heritage Northern Link Phase 2 – Detailed Feasibility Study CHAPTER 12 CULTURAL HERITAGE September 2008 Contents 12. Cultural Heritage 12-1 12.1 Description of the Existing Environment 12-1 12.1.1 Cultural Heritage Significance 12-1 12.1.2 Commonwealth Legislation 12-2 12.1.3 State Legislation 12-2 12.1.4 Local Legislation 12-2 12.1.5 Approach 12-3 12.1.6 Aboriginal Heritage 12-3 12.1.7 Non Indigenous Heritage 12-8 12.2 Impact Assessment 12-17 12.2.1 Western Freeway Connection 12-18 12.2.2 Toowong Connection 12-18 12.2.3 Driven Tunnels 12-19 12.2.4 Kelvin Grove Connection 12-25 12.2.5 Inner City Bypass Connection 12-27 12.2.6 Proposed Ventilation Outlet Sites 12-27 PAGE i 12. Cultural Heritage This chapter addresses Part B, Section 5.8, of the Terms of Reference (ToR), which require the EIS to describe existing values for indigenous and non-indigenous cultural heritage areas and objects that may be affected by Northern Link activities. The ToR also require that the EIS prepare cultural heritage surveys as relevant, to determine the significance of any cultural heritage areas or items and assist with the preparation of Cultural Heritage Management Plans to protect any areas or items of significance. The ToR also require that the EIS provide a description of any likely impacts on cultural heritage values, and to recommend means of mitigating any negative impacts. 12.1 Description of the Existing Environment Cultural heritage focuses on aspects of the past which people value and which are important in identifying who we are.