Light Rail Down Under: Three Strikes and You're Not out !

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oxford Street

Oxford Street The Bulimba District, Brisbane, Australia Project Type: Mixed-Use/Multi-Use Case No: C033007 Year: 2003 SUMMARY A public/private partnership to transform a defunct shopping strip located in the Bulimba District of Brisbane, Australia, into a vibrant, mixed-use district. The catalyst for this transformation is a city-sponsored program to renovate and improve the street and sidewalks along the 0.6-mile (one-kilometer) retail strip of Oxford Street. FEATURES Public/private partnership City-sponsored improvements program Streetscape redevelopment Oxford Street The Bulimba District, Brisbane, Australia Project Type: Mixed-Use/Multi-Use Volume 33 Number 07 April–June 2003 Case Number: C033007 PROJECT TYPE A public/private partnership to transform a defunct shopping strip located in the Bulimba District of Brisbane, Australia, into a vibrant, mixed-use district. The catalyst for this transformation is a city-sponsored program to renovate and improve the street and sidewalks along the 0.6-mile (one-kilometer) retail strip of Oxford Street. SPECIAL FEATURES Public/private partnership City-sponsored improvements program Streetscape redevelopment PROGRAM MANAGER Brisbane City Council Brisbane Administration Center 69 Ann Street Brisbane 4000 Queensland Australia Postal Address GPO Box 1434 Brisbane 4001 Queensland Australia (07) 3403 8888 Fax: (07) 3403 9944 www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/ council_at_work/improving_city/ creating_living_villages/ suburban_centre/index.shtml GENERAL DESCRIPTION Over the past ten years, Oxford Street, located in the Bulimba District of Brisbane, Australia, has been transformed from a defunct shopping strip into a vibrant, mixed-use district. The catalyst for this turnaround is a public/private partnership between Brisbane’s city council and Oxford Street’s local business owners. -

Property Report

PROPERTY REPORT Queensland Softer residential National overview property prices around the country are presenting In this edition of the Westpac Herron Todd White Residential opportunities for Property Report, we are putting the spotlight on the aspiring landlords opportunities for cashed-up investors and self-managed super and DIY superfunds, funds (SMSFs). and we’ll take a look Softer residential property prices around the country are at some of the stand- presenting opportunities for aspiring landlords and DIY out investment real superfunds, and we’ll take a look at some of the stand-out estate markets. investment real estate markets. A buyer’s market With lending still tight and confidence relatively low, competition for quality homes is comparatively thin on the ground, particularly in the entry level markets that are typically popular with investors. While prices are yet to hit bargain basement levels, it’s fair to say they have flattened out. This is good news for cashed-up investors and SMSFs looking for long-term capital gains. Leading the way is the Western Australian market, which has stabilised after a booming period of growth. Similarly, there has been a slight drop in Tasmanian real estate values after 10 years of strong returns. Indeed some markets in and around Hobart, such as Sandy Bay, South Hobart and West Hobart, recorded growth of more than 200% over the last decade. Property a long term investment While buyers, particularly first timers, might be taking a wait-and-see approach, rental markets around Australia are still relatively strong. As a result, vacancy rates are low and this is keeping rents steady, which is good news for investor cash flow. -

Safer School Travel for Runcorn Discover the Urban Stories of Artist Robert Brownhall WHAT's ON

Safer school travel for Runcorn Students at Runcorn Heights State Primary School have received a school travel safety boost after Council completed works as part of the Safe School Travel program. The school has a high percentage of students who walk, cycle, carpool and catch public transport to school. Council recently installed pedestrian safety islands at the school crossing on Nemies Road to improve safety for students and their parents and guardians.The final design of the improvement was decided after consultation with both the school and residents in the area and was delivered with the Queensland Government’s Department of Transport and Main Roads. Council’s Safe School Travel program has operated since 1991 to improve safety across Brisbane’s road network, including children’s daily commute to and from school. The Safe School Travel program delivers about 12 improvement projects each year. Robert Brownhall Story Bridge at Dusk (detail) 2010, City of Brisbane Collection, Museum of Brisbane. WHAT’S ON 7-12 April: Festival of German Films, Palace Centro, Fortitude Valley. 11 & 13 April: Jazzercise (Growing Older and Living Dangerously), 6.30-7.30pm, Calamvale Community College, Calamvale. 15-17 April: Gardening Discover the urban stories of Australia Expo 2011, Brisbane Convention and Exhibition artist Robert Brownhall Centre, www.abcgardening expo.com.au. Get along to Museum of Brisbane from 15 April to experience Brisbane through the eyes of Robert Brownhall. 16-26 April: 21st Century Kids Festival, Gallery of Modern Art, Somewhere in the City: Urban narratives by Robert Brownhall will showcase South Bank, FREE. Brownhall’s quirky style and birds-eye view of Brisbane. -

Gold Coast Highway Multi-Modal Corridor Study

Department of Transport and Main Roads Study finding's Buses Traffic analysis Buses currently play an important role in the movement of people A detailed traffic analysis process was undertaken to determine along and beyond the Gold Coast Highway corridor to a wide the number of traffic lanes, intersection configuration and Gold Coast Highway (Burleigh Heads to Tugun) range of destinations. Consistent with the approach adopted performance of the Gold Coast Highway now and into the future. in the previous stages of the light rail, some bus routes would The analysis confirmed that the nearby Mi (Varsity Lakes to Tugun) be shortened or replaced (such as the current route 700 and upgrade will perform a critical transport function on the southern 777 buses along the Gold Coast Highway), while other services Gold Coast providing the opportunity to: Multi-modal Corridor Study would be maintained and potentially enhanced to offer better • accommodate a significant increase in vehicle demands connectivity overall. including both local demands on service roads and regional demands on the motorway itself. This study has identified the need for buses to continue to connect March 2020 communities to the west of the Gold Coast Highway to key centres • improve local connections to the Mi and service roads including and interchanges with light rail. Connections between bus and a new connection between the Mi and 19th Avenue. light rail will be designed to be safe, convenient and accessible. Planning for the future This significant increase in capacity will provide through traffic Further work between TMR. TransLink and City of Gold Coast will with a viable alternative, reducing demand on the Gold Coast The Department of Transport and Main Roads (TMR) has confirm the design of transport interchanges and the network of Highway. -

Gold Coast Surf Management Plan

Gold Coast Surf Management Plan Our vision – Education, Science, Stewardship Cover and inside cover photo: Andrew Shield Contents Mayor’s foreword 2 Location specifi c surf conditions 32 Methodology 32 Gold Coast Surf Management Plan Southern point breaks – Snapper to Greenmount 33 executive summary 3 Kirra Point 34 Our context 4 Bilinga and Tugun 35 Gold Coast 2020 Vision 4 Currumbin 36 Ocean Beaches Strategy 2013–2023 5 Palm Beach 37 Burleigh Heads 38 Setting the scene – why does the Gold Coast Miami to Surfers Paradise including Nobby Beach, need a Surf Management Plan? 6 Mermaid Beach, Kurrawa and Broadbeach 39 Defi ning issues and fi nding solutions 6 Narrowneck 40 Issue of overcrowding and surf etiquette 8 The Spit 42 Our opportunity 10 South Stradbroke Island 44 Our vision 10 Management of our beaches 46 Our objectives 11 Beach nourishment 46 Objective outcomes 12 Seawall construction 46 Stakeholder consultation 16 Dune management 47 Basement sand excavation 47 Background 16 Tidal works approvals 47 Defi ning surf amenity 18 Annual dredging of Tallebudgera and Currumbin Creek Surf Management Plan Advisory Committee entrances (on-going) 47 defi nition of surf amenity 18 Existing coastal management City projects Defi nition of surf amenity from a scientifi c point of view 18 that consider surf amenity 48 Legislative framework of our coastline 20 The Northern Beaches Shoreline Project (on-going) 48 The Northern Gold Coast Beach Protection Strategy Our beaches – natural processes that form (NGCBPS) (1999-2000) 48 surf amenity on the Gold Coast -

THE ROLE of GOVERNMENT and the CITY of GOLD COAST Which Government for Which Service?

THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT AND THE CITY OF GOLD COAST Which government for which service? LOCAL (COUNCIL) STATE FEDERAL Arts and culture Aboriginal and Torres Strait Aged care Islander partnerships Animal management Census Agriculture and fishing Australian citizenship Child care assistance ceremonies Child safety, youth and Citizenship women Beaches and waterways Constitution Community services Building regulations and Currency and development Conservation and commerce environment State City cleaning The different levels Defence and foreign Consumer affairs and laws of government State government represents the people Community services affairs living in the state they are located in. and centres Corrective services Elections State government members (Members of In the Australian federal system there are Community engagement Disability services and seniors three levels of government: local, state Queensland Parliament) represent specific Immigration areas of the state (electorates). Environmental protection Education and federal. National roads Libraries Fire and emergency services (highways) Each level of government is centred Each state has its own constitution, setting on a body (a parliament or a council) out its own system of government. Lifeguards Health Medicare democratically elected by the people Local roads and footpaths Hospitals Postal services as their representatives. Federal Parks, playgrounds and Housing and public works Social services and In general, each level of government has The Australian Federal Government is the sporting -

12 February 2020 the Chief Executive Officer City of Gold Coast PO Box

12 February 2020 The Chief Executive Officer City of Gold Coast PO Box 5042 GCMC QLD 9729 Via email: [email protected] Dear Mr Dickson Submission during round 2 of public consultation - proposed Major Update 2 & 3 to the Gold Coast City Plan - Our City Our Plan The Planning Institute of Australia (PIA) is the national body representing the planning profession, and planning more broadly, championing the role of planning in shaping Australia’s future. PIA facilitates this through strong leadership, advocacy and contemporary planning education. The Gold Coast Branch of the Queensland Division of PIA had the opportunity to review the proposed Major Update 2 & 3 (the proposed amendment) to the Gold Coast City Plan (City Plan) and provide comment to the City of Gold Coast (CoGC) as part of the first round of public consultation in November 2019. Similarly, we have also reviewed the changed aspects of the proposed amendment which are subject to round 2 of public consultation. Council is commended for responding to the initial round of public consultation by making some significant changes to the proposed amendment and providing the community with the ability to further review and comment on those changes. The introduction of updated environmental mapping to the amendment is also a positive inclusion. As acknowledged in our initial submission, it is understood that CoGC’s program of amendments to the City Plan are being undertaken on a staged basis, with numerous amendment packages underway. The changes contained within the proposed amendment form part of the broader delivery of CoGC’s program and pave the way toward ensuring the City Plan continues to support good planning outcomes for the Gold Coast. -

Department of Government and Political Science Submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts 12 December 1968

A STUDY OF THE PORIIATION OF THE BRISBANE T01\rN PLAN David N, Cox, B.A. Department of Government and Political Science Submitted for the degree of Master of Arts 12 December 1968 CHAPTER I TOWN PLANNING IN BRISBANE TO 1953 The first orderly plans for the City of Brisbane were in the form of an 1840 suirvey preceding the sale of allotments to the public. The original surveyor was Robert Dixon, but he was replaced by Henry Wade in 1843• Wade proposed principal streets ihO links (92,4 ft.) in width, allotments of ^ acre to allow for air space and gardens, public squares, and reserves and roads along 2 the river banks. A visit to the proposed village by the New South Wales Colonial Governor, Sir George Gipps, had infelicitous results. To Gipps, "It was utterly absurd, to lay out a design for a great city in a place which in the very 3 nature of things could never be more than a village." 1 Robinson, R.H., For My Country, Brisbane: W, R. Smith and Paterson Pty. Ltd., 1957, pp. 23-28. 2 Mellor, E.D., "The Changing Face of Brisbane", Journal of the Royal Historical Society. Vol. VI., No. 2, 1959- 1960, pp. 35^-355. 3 Adelaide Town Planning Conference and Exliibition, Official Volume of Proceedings, Adelaide: Vardon and Sons, Ltd., I9I8, p. 119. He went further to say that "open spaces shown on the pleua were highly undesirable, since they might prove an inducement to disaffected persons to assemble k tumultuously to the detriment of His Majesty's peace." The Governor thus eliminated the reserves and river 5 front plans and reduced allotments to 5 to the acre. -

Pdf, 522.77 KB

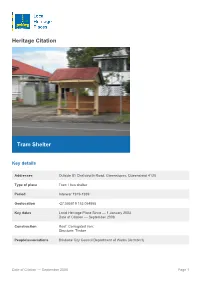

Heritage Citation Tram Shelter Key details Addresses Outside 81 Chatsworth Road, Greenslopes, Queensland 4120 Type of place Tram / bus shelter Period Interwar 1919-1939 Geolocation -27.505819 153.054955 Key dates Local Heritage Place Since — 1 January 2003 Date of Citation — September 2008 Construction Roof: Corrugated iron; Structure: Timber People/associations Brisbane City Council Department of Works (Architect) Date of Citation — September 2008 Page 1 Criterion for listing (A) Historical; (B) Rarity This two-posted double-sided timber tram shelter was constructed by the Brisbane City Council around the 1930s and was originally the terminus of the electric tram route along Chatsworth Road. The shelter is significant for the evidence it provides of Brisbane’s tramway system and for its contribution to the streetscape of Chatsworth Road. History This timber tram shelter is typical of those constructed by the Brisbane City Council on the city’s tram routes during the 1930s. Although it is situated on a tramline constructed in 1914, tram shelters were not generally built during this period, but appeared later as part of the Brisbane City Council’s efforts to improve the tramway system. Brisbane’s association with trams began in August 1885 with the horse tram, owned by the Metropolitan Tramway & Investment Co. In 1895, a contract was let to the Tramways Construction Co. Ltd. of London to electrify the system. The new electric tramway system officially opened on 21 June 1897 when a tram ran from Logan Road to the Victoria Bridge. Other lines opened in that year included the George Street, Red Hill and Paddington lines. -

Pdf, 504.76 KB

Heritage Information Please contact us for more information about this place: [email protected] -OR- phone 07 3403 8888 Hooper's shop (former) Date of Information — August 2006 Page 1 Key details Addresses At 138 Wickham Street, Fortitude Valley, Queensland 4006 Type of place Shop/s Period Interwar 1919-1939 Style Anglo-Dutch Lot plan L3_RP9471 Key dates Local Heritage Place Since — 30 October 2000 Date of Information — August 2006 Construction Walls: Masonry - Render People/associations Chambers and Ford (Architect) Criterion for listing (A) Historical; (E) Aesthetic; (H) Historical association This single storey rendered brick building, designed by notable architects Chambers and Ford, is influenced by the Federation Anglo-Dutch style. It was built in 1922 for jeweller and optometrist George Hooper, who opened a jewellery store that operated until around 1950. It is one of a row of buildings in Wickham Street that form a harmonious streetscape and demonstrate the renewal and growth that occurred in Fortitude Valley in the 1920s. History The Paddy Pallin building is a single storey commercial building designed by Brisbane architects, Chambers and Ford, for owner George Hooper, jeweller and optometrist, who purchased the 6 and 21/100 perch site in July 1922 after subdivision of a larger pre-existing block. This building and others in the block were constructed in the 1920s, replacing earlier buildings, some of which were timber and iron. The 1920s was a decade of economic growth throughout Brisbane. The Valley in particular, with its success as a commercial and industrial hub, expanded even further. Electric trams, which passed the busy corner of Brunswick and Wickham Streets, brought thousands of shoppers to the Valley. -

The Death and Life of Great Australian Music: Planning for Live Music Venues in Australian Cities

The Death and Life of Great Australian Music: planning for live music venues in Australian Cities The Death and Life of Great Australian Music: planning for live music venues in Australian Cities Dr Matthew Burke1 Amy Schmidt2 1Urban Research Program Griffith University 170 Kessels Road Nathan Qld 4111 Australia [email protected] 2Craven Ovenden Town Planning Brisbane, Australia [email protected] Word count: 4,854 words excluding abstract and references Running header: The Death and Life of Great Australian Music Key words: live music, noise, urban planning, entertainment precincts Abstract In recent decades outdated noise, planning and liquor laws, encroaching residential development, and the rise of more lucrative forms of entertainment for venue operators, such as poker machines, have acted singly or in combination to close many live music venues in Australia. A set of diverse and quite unique policy and planning initiatives have emerged across Australia’s cities responding to these threats. This paper provides the results of a systematic research effort conducted in 2008 into the success or otherwise of these approaches in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne. Archival and legislative reviews and field visits were supplemented by interviews with key authorities, venue operators, live music campaigners and others in each city. The research sought to categorise and evaluate the diverse approaches being used and to attempt to understand best ways forward to maintain opportunities for live music performance. In Brisbane a place-based approach designating ‘Entertainment Precincts’ has been used, re-writing separate pieces of legislation (across planning, noise and liquor law). Resulting in monopolies for the few venue operators within the precincts, outside the threats remain and venues continue to be lost. -

GOLD COAST COMMUNITY SERVICES DIRECTORY Apps and SERVICE DIRECTORIES BEHAVIOUR SUPPORT

GOLD COAST COMMUNITY SERVICES DIRECTORY APPs AND SERVICE DIRECTORIES BEHAVIOUR SUPPORT CHILD SAFETY CHILDCARE / DAYCARE CLOTHING AND FURNITURE ASSISTANCE COMMUNITY AND NEIGHBOURHOOD CENTRES (Range of services) COUNSELLING – ADULT AND FAMILY COUNSELLING – CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE CRISIS HELPLINES DISABILITY DISABILITY RESPITE DOMESTIC VIOLENCE DRUG AND ALCOHOL EDUCATION – ALTERNATIVE OPTIONS EMPLOYMENT FAMILY SUPPORT SERVICES FINANCIAL ADVICE / ASSISTANCE FOOD ASSISTANCE – COASTWIDE FOOD ASSISTANCE AND FOODBANKS - NORTHERN GOLD COAST FOOD ASSISTANCE AND FOODBANKS - SOUTHERN GOLD COAST GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENTS HEALTH AND DEVELOPMENTAL HOMELESSNESS AND CRISIS ACCOMMODATION HOUSING AND TENANCY INDIGENOUS SERVICES LEGAL LGBTIQ+ SERVICES MEN’S SERVICES MENTAL HEALTH MULTICULTURAL SERVICES PARENTING PREGNANCY RESPITE SEXUAL ABUSE YOUTH For information, advice and referral information, please contact Family and Child Connect (FaCC) on 13FAMILY or 5508 3835 Information contained in this document has been collated by Act for Kids. Please contact 07 5508 3835 if any of the details listed require updating. Last updated 6th February 2020. APPs AND SERVICE DIRECTORIES 7 Care Connect Register at 7careconnect.com A web based application and navigation tool which FREE access via Smart Phone, Tablet, displays service locations and information for people Computer and City Libraries who are experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness. Sign up to receive real-time updates on local services, transport and community events. Choose the service you need and what’s local to you – Safety, Food, Accommodation, Support, Social Needs, Health, Learn/Earn. Lifeline Service Finder App Downloadable on Smart Phones National directory of health and community services linking with more than 85 000 free and low cost services across Australia. My Community Directory www.mycommunitydirectory.com.au Online search directory for community services.