Inner-Urban Sustainability: a Case Study of the South Brisbane Peninsula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oxford Street

Oxford Street The Bulimba District, Brisbane, Australia Project Type: Mixed-Use/Multi-Use Case No: C033007 Year: 2003 SUMMARY A public/private partnership to transform a defunct shopping strip located in the Bulimba District of Brisbane, Australia, into a vibrant, mixed-use district. The catalyst for this transformation is a city-sponsored program to renovate and improve the street and sidewalks along the 0.6-mile (one-kilometer) retail strip of Oxford Street. FEATURES Public/private partnership City-sponsored improvements program Streetscape redevelopment Oxford Street The Bulimba District, Brisbane, Australia Project Type: Mixed-Use/Multi-Use Volume 33 Number 07 April–June 2003 Case Number: C033007 PROJECT TYPE A public/private partnership to transform a defunct shopping strip located in the Bulimba District of Brisbane, Australia, into a vibrant, mixed-use district. The catalyst for this transformation is a city-sponsored program to renovate and improve the street and sidewalks along the 0.6-mile (one-kilometer) retail strip of Oxford Street. SPECIAL FEATURES Public/private partnership City-sponsored improvements program Streetscape redevelopment PROGRAM MANAGER Brisbane City Council Brisbane Administration Center 69 Ann Street Brisbane 4000 Queensland Australia Postal Address GPO Box 1434 Brisbane 4001 Queensland Australia (07) 3403 8888 Fax: (07) 3403 9944 www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/ council_at_work/improving_city/ creating_living_villages/ suburban_centre/index.shtml GENERAL DESCRIPTION Over the past ten years, Oxford Street, located in the Bulimba District of Brisbane, Australia, has been transformed from a defunct shopping strip into a vibrant, mixed-use district. The catalyst for this turnaround is a public/private partnership between Brisbane’s city council and Oxford Street’s local business owners. -

Property Report

PROPERTY REPORT Queensland Softer residential National overview property prices around the country are presenting In this edition of the Westpac Herron Todd White Residential opportunities for Property Report, we are putting the spotlight on the aspiring landlords opportunities for cashed-up investors and self-managed super and DIY superfunds, funds (SMSFs). and we’ll take a look Softer residential property prices around the country are at some of the stand- presenting opportunities for aspiring landlords and DIY out investment real superfunds, and we’ll take a look at some of the stand-out estate markets. investment real estate markets. A buyer’s market With lending still tight and confidence relatively low, competition for quality homes is comparatively thin on the ground, particularly in the entry level markets that are typically popular with investors. While prices are yet to hit bargain basement levels, it’s fair to say they have flattened out. This is good news for cashed-up investors and SMSFs looking for long-term capital gains. Leading the way is the Western Australian market, which has stabilised after a booming period of growth. Similarly, there has been a slight drop in Tasmanian real estate values after 10 years of strong returns. Indeed some markets in and around Hobart, such as Sandy Bay, South Hobart and West Hobart, recorded growth of more than 200% over the last decade. Property a long term investment While buyers, particularly first timers, might be taking a wait-and-see approach, rental markets around Australia are still relatively strong. As a result, vacancy rates are low and this is keeping rents steady, which is good news for investor cash flow. -

Safer School Travel for Runcorn Discover the Urban Stories of Artist Robert Brownhall WHAT's ON

Safer school travel for Runcorn Students at Runcorn Heights State Primary School have received a school travel safety boost after Council completed works as part of the Safe School Travel program. The school has a high percentage of students who walk, cycle, carpool and catch public transport to school. Council recently installed pedestrian safety islands at the school crossing on Nemies Road to improve safety for students and their parents and guardians.The final design of the improvement was decided after consultation with both the school and residents in the area and was delivered with the Queensland Government’s Department of Transport and Main Roads. Council’s Safe School Travel program has operated since 1991 to improve safety across Brisbane’s road network, including children’s daily commute to and from school. The Safe School Travel program delivers about 12 improvement projects each year. Robert Brownhall Story Bridge at Dusk (detail) 2010, City of Brisbane Collection, Museum of Brisbane. WHAT’S ON 7-12 April: Festival of German Films, Palace Centro, Fortitude Valley. 11 & 13 April: Jazzercise (Growing Older and Living Dangerously), 6.30-7.30pm, Calamvale Community College, Calamvale. 15-17 April: Gardening Discover the urban stories of Australia Expo 2011, Brisbane Convention and Exhibition artist Robert Brownhall Centre, www.abcgardening expo.com.au. Get along to Museum of Brisbane from 15 April to experience Brisbane through the eyes of Robert Brownhall. 16-26 April: 21st Century Kids Festival, Gallery of Modern Art, Somewhere in the City: Urban narratives by Robert Brownhall will showcase South Bank, FREE. Brownhall’s quirky style and birds-eye view of Brisbane. -

Brisbane Native Plants by Suburb

INDEX - BRISBANE SUBURBS SPECIES LIST Acacia Ridge. ...........15 Chelmer ...................14 Hamilton. .................10 Mayne. .................25 Pullenvale............... 22 Toowong ....................46 Albion .......................25 Chermside West .11 Hawthorne................. 7 McDowall. ..............6 Torwood .....................47 Alderley ....................45 Clayfield ..................14 Heathwood.... 34. Meeandah.............. 2 Queensport ............32 Trinder Park ...............32 Algester.................... 15 Coopers Plains........32 Hemmant. .................32 Merthyr .................7 Annerley ...................32 Coorparoo ................3 Hendra. .................10 Middle Park .........19 Rainworth. ..............47 Underwood. ................41 Anstead ....................17 Corinda. ..................14 Herston ....................5 Milton ...................46 Ransome. ................32 Upper Brookfield .......23 Archerfield ...............32 Highgate Hill. ........43 Mitchelton ...........45 Red Hill.................... 43 Upper Mt gravatt. .......15 Ascot. .......................36 Darra .......................33 Hill End ..................45 Moggill. .................20 Richlands ................34 Ashgrove. ................26 Deagon ....................2 Holland Park........... 3 Moorooka. ............32 River Hills................ 19 Virginia ........................31 Aspley ......................31 Doboy ......................2 Morningside. .........3 Robertson ................42 Auchenflower -

Inner Brisbane Heritage Walk/Drive Booklet

Engineering Heritage Inner Brisbane A Walk / Drive Tour Engineers Australia Queensland Division National Library of Australia Cataloguing- in-Publication entry Title: Engineering heritage inner Brisbane: a walk / drive tour / Engineering Heritage Queensland. Edition: Revised second edition. ISBN: 9780646561684 (paperback) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Brisbane (Qld.)--Guidebooks. Brisbane (Qld.)--Buildings, structures, etc.--Guidebooks. Brisbane (Qld.)--History. Other Creators/Contributors: Engineers Australia. Queensland Division. Dewey Number: 919.43104 Revised and reprinted 2015 Chelmer Office Services 5/10 Central Avenue Graceville Q 4075 Disclaimer: The information in this publication has been created with all due care, however no warranty is given that this publication is free from error or omission or that the information is the most up-to-date available. In addition, the publication contains references and links to other publications and web sites over which Engineers Australia has no responsibility or control. You should rely on your own enquiries as to the correctness of the contents of the publication or of any of the references and links. Accordingly Engineers Australia and its servants and agents expressly disclaim liability for any act done or omission made on the information contained in the publication and any consequences of any such act or omission. Acknowledgements Engineers Australia, Queensland Division acknowledged the input to the first edition of this publication in 2001 by historical archaeologist Kay Brown for research and text development, historian Heather Harper of the Brisbane City Council Heritage Unit for patience and assistance particularly with the map, the Brisbane City Council for its generous local history grant and for access to and use of its BIMAP facility, the Queensland Maritime Museum Association, the Queensland Museum and the John Oxley Library for permission to reproduce the photographs, and to the late Robin Black and Robyn Black for loan of the pen and ink drawing of the coal wharf. -

Woolloongabba to the University of Queensland (UQ)

BRACKEN RDGE RD BRACKEN RDGE RD WARNER GMPE RD KREMW RD BRACKEN RIDE LD N RD DENHAM ST SANDATE S PNE RD BARD ST PHLLPS ST S PNE RD DEAN SHRNCLIE BRENDALE EATONS CRO NRRS RD SSI NG LNKFELD RD GMPE ARTERAL RD R D S PNE RD TELEGRAPH RD G Y M P I E R D G ATEW AY MOTORWAY D R E K M LE LACE RD EATNS RDLE RD RGHAN RD HILL BEAMS RD ALBAN GMPE RD CREEK CARSELDINE BNDALL TAIUM DRVLLE RD ITIBBN BEAMS RD ALB AN Y C RE GRAHAM RD HANDFRD RD NUDEE EK KENG RD RD BEACH BRIDEMAN GA TEW AY DWNS MOT ORW LLMERE RD AY ILLMERE SANDGATE RD LLMERE RD KRB RD RBNSN RD W BECKETT RD ASLE BUNA HRN RD RBNSN RD W NUDEE MURPH RD EEBUN TRACK KER JIN ELLSN RD VIRINIA BAN MAUNDRELLCHERMSIDE TCE MCDWALL WEST K ST VNCENTS RD ITTY HAMLTN RD H O L A D NEWMAN RD TUFNELL RD W N K O BUNA RD D NRTHATE R T R H E R N MAN AVE EARNSHAW RD R TRUTS RD D D HAMLTN RD R CHERMSIDE E TMBUL RD T A G NUDGEE RD RDE RD D N A S WAVELL EVERTN HEIHTS G FLCKTN ST Y HILLS M RDE RD ARPRT DR P I C E A PATRCKS RD M D STARD R E R D L MELTN RD IA EVERTN S T HEIHTS A V U E PARK O R T ARANA DAWSN PDE TMBUL S FELSTEAD ST HILLS P MRETN DR I N SHAW RD E NUNDAH R REDWD ST D BUCKLAND RD KEDRN APPLEB RD WDDP ST WEBSTER RD MITCHELTN KEERRA STAFFRD RD ARPRT DR RDN D PARK R RO K SE ST R PA T S D N A GERLER RD H S THSTLE ST T LTTN S BRADSHAW ST LMANDRA DR E LMANDRA DR ATHRNE G D I RAMNT RD R RANE B S O U T H R D E RT R PO BNNE AVE FULLER ST STNELEGH ST N PRTCHARD ST C KTCHENER RD R D REL RD O D DAS RD R R YGAR S A M ST LUTWCHE D S M R N NUDGEE RD R D W O A K L F A S A E E D N D Y L D U Y R O G ALBN RD H A R D ASCT -

DNRM RTI DL Release

Author: G. Swann File Number: 190 ~7 'I Woolloongabba Office South East Region Phone: 3224 7373 5 July2007 Rinker Australia Pty Ltd PO Box 1143 Milton Q 4067 Attention - Operations Manager - Dear Sir Information Notice - Renewal of Quarry Material Allocation Notice Number: 100740 This information notice is given in accordance with section 289 (5) ofthe Water Act 2000 ("the Act") in respect of the decision on the above application.Release Background Matters DL This allocation refers to the extraction of quarry materials from the Brisbane River at a location known as Summerville's Land (Left Bank). Decision RTI The Department ofNatural Resources and Water delegates officers to exercise the power of the chief executive to make decisions about applications for a renewal of a Quarry Material - Allocation. As a delegated officer of this Department, I have decided to grant with conditions the above application and provideDNRM the following information about my decision. This information notice is advice of my decision and the reasons for the decision. Copies of this information notice have been sent to all persons who made a properly made submission with respect to the application. Evidence Or Other Material On Which Findings Of Fact Were Made Renewal of this allocation has been issued for the same maximum extraction rate as previously issued. Level 3 Landcentre Cnr Main & Vulture Streets Woolloongabba Qld 4102 PO Box 1653 Coorparoo Queensland 4151 Australia Telephone + 61 7 32247373 Facsimile + 61 7 32242933 Website www.nrm.qld.gov.au 14-203 File H Page 1 of 42 Release Findings On Material Questions Of Fact • Renewal and transfer application made by Rinker Australia Pty Ltd which was received on 26 February 2007 with prescribed fee. -

Kangaroo Point M Apartments Kangaroo Point

DARK FINISHES KANGAROO POINT M APARTMENTS KANGAROO POINT Sophisticated living in a hotspot urban village. Location, design, quality and value: M Apartments put it all on the table for you at Kangaroo Point – transforming before our eyes into Brisbane’s most dynamic new urban environment. Close to the city, close to everything. The coolest places to meet and mingle, eat and shop, just a hop, skip and jump from transport, nightlife, parks and open spaces. In an area that mixes the old with the new and the unexpected, M Apartments radiate cool. Think flair plus functionality, ultra-smart aesthetics, space and comfort. Make your move and secure a vibrant slice of cosmopolitan life, in a locale primed for future growth. M Apartments, Kangaroo Point. 02 03 M APARTMENTS KANGAROO POINT A location brimming with energy and vitality. Kangaroo Point is booming and demand is rising, in this ultra-convenient and connected neighbourhood only 1.5km across the river from the CBD. Capturing the buzz of inner-city living and echoing Kangaroo Point’s revitalized contemporary edge, M Apartments will be the sought-after home for up and coming professionals, students at the nearby tertiary campuses, astute downsizers and investors with a keen eye for capital gains. It’s all here for the taking, in this one-of- a-kind location. Stroll, hop on a CityCat or ferry, catch the bus or drive the Clem7 cross-river tunnel. A new green bridge is planned, to link Kangaroo Point even more closely with the CBD. Plus, easy proximity to Woolloongabba, South Bank, Fortitude Valley, the clubs, pubs, bars, dining spots and designer stores puts Kangaroo Point clearly at the centre of Brisbane’s property radar. -

Department of Government and Political Science Submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts 12 December 1968

A STUDY OF THE PORIIATION OF THE BRISBANE T01\rN PLAN David N, Cox, B.A. Department of Government and Political Science Submitted for the degree of Master of Arts 12 December 1968 CHAPTER I TOWN PLANNING IN BRISBANE TO 1953 The first orderly plans for the City of Brisbane were in the form of an 1840 suirvey preceding the sale of allotments to the public. The original surveyor was Robert Dixon, but he was replaced by Henry Wade in 1843• Wade proposed principal streets ihO links (92,4 ft.) in width, allotments of ^ acre to allow for air space and gardens, public squares, and reserves and roads along 2 the river banks. A visit to the proposed village by the New South Wales Colonial Governor, Sir George Gipps, had infelicitous results. To Gipps, "It was utterly absurd, to lay out a design for a great city in a place which in the very 3 nature of things could never be more than a village." 1 Robinson, R.H., For My Country, Brisbane: W, R. Smith and Paterson Pty. Ltd., 1957, pp. 23-28. 2 Mellor, E.D., "The Changing Face of Brisbane", Journal of the Royal Historical Society. Vol. VI., No. 2, 1959- 1960, pp. 35^-355. 3 Adelaide Town Planning Conference and Exliibition, Official Volume of Proceedings, Adelaide: Vardon and Sons, Ltd., I9I8, p. 119. He went further to say that "open spaces shown on the pleua were highly undesirable, since they might prove an inducement to disaffected persons to assemble k tumultuously to the detriment of His Majesty's peace." The Governor thus eliminated the reserves and river 5 front plans and reduced allotments to 5 to the acre. -

Pdf, 522.77 KB

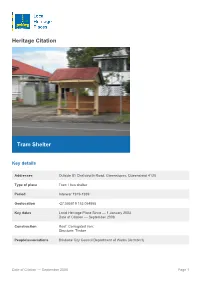

Heritage Citation Tram Shelter Key details Addresses Outside 81 Chatsworth Road, Greenslopes, Queensland 4120 Type of place Tram / bus shelter Period Interwar 1919-1939 Geolocation -27.505819 153.054955 Key dates Local Heritage Place Since — 1 January 2003 Date of Citation — September 2008 Construction Roof: Corrugated iron; Structure: Timber People/associations Brisbane City Council Department of Works (Architect) Date of Citation — September 2008 Page 1 Criterion for listing (A) Historical; (B) Rarity This two-posted double-sided timber tram shelter was constructed by the Brisbane City Council around the 1930s and was originally the terminus of the electric tram route along Chatsworth Road. The shelter is significant for the evidence it provides of Brisbane’s tramway system and for its contribution to the streetscape of Chatsworth Road. History This timber tram shelter is typical of those constructed by the Brisbane City Council on the city’s tram routes during the 1930s. Although it is situated on a tramline constructed in 1914, tram shelters were not generally built during this period, but appeared later as part of the Brisbane City Council’s efforts to improve the tramway system. Brisbane’s association with trams began in August 1885 with the horse tram, owned by the Metropolitan Tramway & Investment Co. In 1895, a contract was let to the Tramways Construction Co. Ltd. of London to electrify the system. The new electric tramway system officially opened on 21 June 1897 when a tram ran from Logan Road to the Victoria Bridge. Other lines opened in that year included the George Street, Red Hill and Paddington lines. -

Looking at a Strengthening Market and How to Act

APARTMENT In this edition of Apartment Magazine, we look at why you should consider buying new and some of the hidden costs ISSUE 09 associated with purchasing a property. Our team also delve into the stats and report on the strengthening market in SUMMER 19/20 South East Queensland, and how Kangaroo Point is being rediscovered as a dominant player in the Brisbane market. LOOKING AT A STRENGTHENING MARKET AND HOW TO ACT NOW WHY PLACE PROJECTS FOR YOUR INVESTMENT? It’s a seamless approach with your investment, from purchase to management. Place Projects Property Management builds relationships starting with YOU. As our client, you will receive a high level of communication from experienced property managers. 07 3107 9223 We have a boutique portfolio and pay attention to maximise [email protected] your investment return. We focus on tenant selection and work Level 1, 33 Lytton Road hard to keep your investment producing for the long term. East Brisbane IS THERE ANY BENEFIT IN BUYING A NEW PROPERTY? APART FROM THE OBVIOUS AND DESIRABLE NEW FEEL AND LOOK, THERE ARE SEVERAL OTHER REASONS WHY BUYING A NEW PROPERTY CAN PAY OFF. Firstly, first home buyers have a huge benefit of receiving $15,000 cash if they purchase a new home for less than $750,000. Secondly, the chance of unforeseen repairs is lower for newer properties and may still be covered under warranty. Additionally, body corporate contributions can be considerably less than some older units that need to boost the WHY BUY amount in the sinking fund. There is also extra security in knowing that if you decide to rent out your new property that you will get a premium price compared to established properties. -

Pdf, 504.76 KB

Heritage Information Please contact us for more information about this place: [email protected] -OR- phone 07 3403 8888 Hooper's shop (former) Date of Information — August 2006 Page 1 Key details Addresses At 138 Wickham Street, Fortitude Valley, Queensland 4006 Type of place Shop/s Period Interwar 1919-1939 Style Anglo-Dutch Lot plan L3_RP9471 Key dates Local Heritage Place Since — 30 October 2000 Date of Information — August 2006 Construction Walls: Masonry - Render People/associations Chambers and Ford (Architect) Criterion for listing (A) Historical; (E) Aesthetic; (H) Historical association This single storey rendered brick building, designed by notable architects Chambers and Ford, is influenced by the Federation Anglo-Dutch style. It was built in 1922 for jeweller and optometrist George Hooper, who opened a jewellery store that operated until around 1950. It is one of a row of buildings in Wickham Street that form a harmonious streetscape and demonstrate the renewal and growth that occurred in Fortitude Valley in the 1920s. History The Paddy Pallin building is a single storey commercial building designed by Brisbane architects, Chambers and Ford, for owner George Hooper, jeweller and optometrist, who purchased the 6 and 21/100 perch site in July 1922 after subdivision of a larger pre-existing block. This building and others in the block were constructed in the 1920s, replacing earlier buildings, some of which were timber and iron. The 1920s was a decade of economic growth throughout Brisbane. The Valley in particular, with its success as a commercial and industrial hub, expanded even further. Electric trams, which passed the busy corner of Brunswick and Wickham Streets, brought thousands of shoppers to the Valley.