Exploring the Esports Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

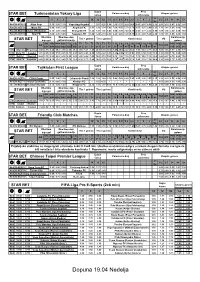

Dopuna 19.04 Nedelja

Dupla Prvo Poluvreme-kraj Ukupno golova STAR BET Turkmenistan Yokary Liga šansa poluvreme 2+ 1 X 2 1X 12 X2 1-1 X-1 X-X X-2 2-2 1 X 2 0-2 2-3 3+ 4+ 5+ 1p. Ned 14:00 5232 Altyn Asyr 1.15 5.90 13.0 Kopetdag Asgabat - 1.07 4.25 1.54 3.90 9.75 28.0 24.0 1.49 2.65 8.50 2.12 2.55 2.15 1.41 2.12 3.65 Pon 13:30 5709 Merw FK 2.90 3.00 2.25 Asgabat FK 1.51 1.29 1.31 5.00 7.00 4.55 5.70 3.70 3.55 1.97 2.80 2.95 1.70 1.91 1.96 3.60 7.60 Pon 14:00 5707Nebitci (FK Balkan) 2.15 2.80 3.40 Energetik FK 1.24 1.33 1.56 3.65 5.00 3.80 7.40 6.10 2.90 1.77 4.25 3.90 1.39 1.96 2.62 5.60 13.0 Pon 15:30 5708 Ahal FK 1.60 3.30 5.45 Sagadam FK 1.09 1.24 2.10 2.50 4.25 4.85 12.0 9.75 2.15 2.03 5.20 2.90 1.70 1.91 1.95 3.55 7.50 Oba tima Oba tima daju Kombinacije Tim 1 golova Tim 2 golova Kombinacije VG STAR BET daju gol gol kombinacije golova GG GG GG1& GG1/ 1 & 2 & T1 T1 T1 T2 T2 T2 1 & 2 & 1 & 2 & 1-1& 2-2& 1-1& 2-2& 1+I& 1+I& 2+I& GG 1>2 2>1 &3+ &4+ GG2 GG2 GG GG 2+ I 2+ 3+ 2+ I 2+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 4+ 4+ 3+ 3+ 4+ 4+ 1+II 2+II 2+II 5232 Altyn As Kopetdag 2.08 2.35 3.20 18.0 2.30 2.80 23.0 2.80 1.21 1.80 20.0 6.60 28.0 1.49 28.0 2.22 60.0 1.96 50.0 2.75 80.0 3.00 1.85 1.37 2.10 3.70 5709 Merw FK Asgabat 1.76 2.25 3.80 17.0 2.25 6.10 4.55 9.25 2.85 8.00 7.00 2.22 5.35 5.35 4.00 11.0 9.00 9.00 6.50 18.0 13.0 3.10 2.00 1.74 3.20 6.80 5707 Nebitci Energeti 2.22 3.10 5.90 29.0 2.90 5.80 9.00 9.00 2.62 7.00 14.0 4.15 14.0 4.75 7.90 13.0 19.0 7.70 14.0 17.0 35.0 3.25 2.07 2.15 4.50 11.0 5708 Ahal FK Sagadam 2.00 2.55 4.15 21.0 2.45 3.75 11.0 5.10 1.73 3.45 15.0 4.75 18.0 2.75 12.0 5.60 27.0 3.95 21.0 7.10 55.0 3.10 2.00 1.73 3.15 6.75 Dupla Prvo Poluvreme-kraj Ukupno golova STAR BET Tajikistan First League šansa poluvreme 2+ 1 X 2 1X 12 X2 1-1 X-1 X-X X-2 2-2 1 X 2 0-2 2-3 3+ 4+ 5+ 1p. -

Dodatok Za 13.04. Ponedelnik Конечен Рез

Двојна Прво Полувреме-крај Вкупно голови Sport Life Belarus 1 шанса полувреме 2+ 1 X 2 1X 12 X2 1-1 X-1 X-X X-2 2-2 1 X 2 0-2 2-3 3+ 4+ 5+ 1п. Пон 16:30 3537 Slavia-Mozyr 1.92 3.053.75 Rukh Brest 1.19 1.29 1.71 3.154.75 4.30 8.25 6.60 2.62 1.88 4.33 3.35 1.52 1.92 2.25 4.45 10.0 Двата тима Двата тима Комбиниран Тим 1 голови Тим 2 голови Комбинирани типови ППГ Sport Life даваат гол даваат гол комб. тип голови ГГ ГГГГ1& ГГ1/ 1 & 2 & T1 T1 T1 T2 T2 T2 1 & 2 & 1 & 2 & 1-1& 2-2& 1-1& 2-2& 1+I& 1+I& 2+I& ГГ 1>2 2>1 &3+ &4+ ГГ2 ГГ2 ГГ ГГ 2+ I 2+ 3+ 2+ I 2+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 4+ 4+ 3+ 3+ 4+ 4+ 1+II 2+II 2+II 3537Slavia-M Rukh Bre 2.04 2.70 4.8523.0 2.60 4.65 9.00 7.10 2.20 5.25 13.0 4.00 14.0 3.70 8.00 8.50 18.0 5.80 14.0 11.0 35.0 3.15 2.04 1.93 3.80 8.75 Двојна Прво Полувреме-крај Вкупно голови Sport Life Nicaragua Premiera Division шанса полувреме 2+ 1X2X 2 1X 12 1-1 X-1 X-X X-2 2-2 1 X 2 0-2 2-3 3+ 4+ 5+ 1п. -

Sports & Esports the Competitive Dream Team

SPORTS & ESPORTS THE COMPETITIVE DREAM TEAM JULIANA KORANTENG Editor-in-Chief/Founder MediaTainment Finance (UK) SPORTS & ESPORTS: THE COMPETITIVE DREAM TEAM 1.THE CROSSOVER: WHAT TRADITIONAL SPORTS CAN BRING TO ESPORTS Professional football, soccer, baseball and motor racing have endless decades worth of experience in professionalising, commercialising and monetising sporting activities. In fact, professional-services powerhouse KPMG estimates that the business of traditional sports, including commercial and amateur events, related media as well as education, academic, grassroots and other ancillary activities, is a US$700bn international juggernaut. Furthermore, the potential crossover with esports makes sense. A host of popular video games have traditional sports for themes. Soccer-centric games include EA’s FIFA series and Konami’s Pro Evolution Soccer. NBA 2K, a series of basketball simulation games published by a subsidiary of Take-Two Interactive, influenced the formation of the groundbreaking NBA 2K League in professional esports. EA is also behind the Madden NFL series plus the NHL, NBA, FIFA and UFC (Ultimate Fighting Championship) games franchises. Motor racing has influenced the narratives in Rockstar Games’ Grand Theft Auto, Gran Turismo from Sony Interactive Entertainment, while Psyonix’s Rocket League melds soccer and motor racing. SPORTS & ESPORTS THE COMPETITIVE DREAM TEAM SPORTS & ESPORTS: THE COMPETITIVE DREAM TEAM In some ways, it isn’t too much of a stretch to see why traditional sports should appeal to the competitive streaks in gamers. Not all those games, several of which are enjoyed by solitary players, might necessarily translate well into the head-to-head combat formats associated with esports and its millions of live-venue and online spectators. -

From Meltdown to Showdown? Challenges and Options for Governance in the Arctic

PRIF-Report No. 113 From Meltdown to Showdown? Challenges and options for governance in the Arctic Christoph Humrich/Klaus Dieter Wolf Translation: Matthew Harris Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) 2012 Correspondence to: PRIF (HSFK) Baseler Straße 27-31 60329 Frankfurt am Main Germany Telephone: +49(0)69 95 91 04-0 Fax: +49(0)69 55 84 81 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Internet: www.prif.org ISBN: 978-3-942532-41-9 Euro 10,– Summary Over the past few years the Arctic has become the object of intense political interest. Three interacting developments created this interest: first, climate change which is caus- ing the polar ice cap to melt is creating new opportunities and risks. While huge areas open up to resource development, this seems at the same time to also cause new geo- strategic confrontation. The second development is economic change. In Russia, Green- land, Norway and Alaska, economic well-being is highly dependent upon the exploitation of natural resources. Because on the one hand export revenues are rising for natural re- sources and on the other already developed sources further south have transgressed their exploitation peak, the economies of these countries drive them up North into the high Arctic. Thirdly, there has been legal change. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides a legal framework for exploiting continental shelf re- sources. The Arctic states can and must assert their claims now. Contrary to all alarmist pronouncements, however, the process of delimiting the boundaries of the continental shelf is proceeding in a relatively orderly manner . -

Comunicacion Y Videojuegos.Pdf

COMUNICACIÓN Y VIDEOJUEGOS. REFLEJANDO LA SOCIEDAD A TRAVÉS DEL OCIO INTERACTIVO — Colección Comunicación y Pensamiento — COMUNICACIÓN Y VIDEOJUEGOS. REFLEJANDO LA SOCIEDAD A TRAVÉS DEL OCIO INTERACTIVO Editor Guillermo Paredes-Otero Autores (por orden de aparición) Guillermo Paredes-Otero Antonio César Moreno Cantano Carlos Álvarez Barroso Jesús Albarrán Ligero Antonio Fco. Campos Méndez Sergio Jesús Villén Higueras Augusto David Beltrán Poot Fernando Martínez López Rafael Jaén Pozo COMUNICACIÓN Y VIDEOJUEGOS. REFLEJANDO LA SOCIEDAD A TRAVÉS DEL OCIO INTERACTIVO Ediciones Egregius www.egregius.es Diseño de cubierta y maquetación: Francisco Anaya Benítez © de los textos: los autores © de la presente edición: Ediciones Egregius N.º 65 de la colección Comunicación y Pensamiento 1ª edición, 2020 ISBN 978-84-18167-35-5 NOTA EDITORIAL: Las opiniones y contenidos publicados en esta obra son de responsabilidad exclusiva de sus autores y no reflejan necesariamente la opinión de Ediciones Egregius ni de los editores o coordinadores de la publicación; asimismo, los autores se responsabilizarán de obtener el permiso correspondiente para incluir material publicado en otro lugar. Colección: Comunicación y Pensamiento Los fenómenos de la comunicación invaden todos los aspectos de la vida cotidiana, el acontecer contemporáneo es imposible de comprender sin la perspectiva de la comu- nicación, desde su más diversos ámbitos. En esta colección se reúnen trabajos acadé- micos de distintas disciplinas y materias científicas que tienen como elemento común la comunicación y el pensamiento, pensar la comunicación, reflexionar para com- prender el mundo actual y elaborar propuestas que repercutan en el desarrollo social y democrático de nuestras sociedades. La colección reúne una gran cantidad de trabajos procedentes de muy distintas partes del planeta, un esfuerzo conjunto de profesores investigadores de universidades e ins- tituciones de reconocido prestigio. -

Esports Yearbook 2017/18

Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz eSports Yearbook 2017/18 ESPORTS YEARBOOK Editors: Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz Layout: Tobias M. Scholz Cover Photo: Adela Sznajder, ESL Copyright © 2019 by the Authors of the Articles or Pictures. ISBN: to be announced Production and Publishing House: Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt. Printed in Germany 2019 www.esportsyearbook.com eSports Yearbook 2017/18 Editors: Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz Contributors: Sean Carton, Ruth S. Contreras-Espinosa, Pedro Álvaro Pereira Correia, Joseph Franco, Bruno Duarte Abreu Freitas, Simon Gries, Simone Ho, Matthew Jungsuk Howard, Joost Koot, Samuel Korpimies, Rick M. Menasce, Jana Möglich, René Treur, Geert Verhoeff Content The Road Ahead: 7 Understanding eSports for Planning the Future By Julia Hiltscher and Tobias M. Scholz eSports and the Olympic Movement: 9 A Short Analysis of the IOC Esports Forum By Simon Gries eSports Governance and Its Failures 20 By Joost Koot In Hushed Voices: Censorship and Corporate Power 28 in Professional League of Legends 2010-2017 By Matthew Jungsuk Howard eSports is a Sport, but One-Sided Training 44 Overshadows its Benefits for Body, Mind and Society By Julia Hiltscher The Benefits and Risks of Sponsoring eSports: 49 A Brief Literature Review By Bruno Duarte Abreu Freitas, Ruth S. Contreras-Espinosa and Pedro Álvaro Pereira Correia - 5 - Sponsorships in eSports 58 By Samuel Korpimies Nationalism in a Virtual World: 74 A League of Legends Case Study By Simone Ho Professionalization of eSports Broadcasts 97 The Mediatization of DreamHack Counter-Strike Tournaments By Geert Verhoeff From Zero to Hero, René Treurs eSports Journey. -

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest My Name: Tomi Kovanen My Date of Birth: January 16, 1988 Team Name: MIBR Team Formation Date: June 23, 2018 This is an exhaustive list of the conflicts of interest and business entanglements I have with players and teams that I expect to compete against in professional tournaments. Business entanglement include, but are not limited to, shared management, shared ownership of entities, licensing, and loans. I understand that failure to report my conflicts of interest may result in my disqualification from events and/or forfeiture of proceeds. Number of Pages Attached: 2 Signature: Date: April 17, 2020 Page 1 / 3 Other party: ENCE Nature of conflict: IGC SVP Finance and Business Development Tomi Kovanen, who is among the senior leadership of the company overseeing the MIBR brand, is also a minority shareholder in ENCE, who were qualified for ESL One Rio de Janeiro and now compete in the RMR qualification system in Europe. Other party: YeaH Gaming Nature of conflict: MIBR parent company IGC has an agreement with YeaH. In exchange for a set annual fee payable regardless of actual roster changes, IGC has an option to buy out at most 2 players from YeaH Gaming’s roster in a calendar year at an agreed upon price. Other party: BLAST Premier and its partner teams (Natus Vincere, Astralis, Liquid, FaZe, Vitality, NiP, 100 Thieves, OG, G2, Evil Geniuses, Complexity) Nature of conflict: IGC (MIBR’s parent company) has a broad agreement for participation in BLAST Premier together with many other teams that are competing in various RMR regions to qualify for the Major. -

Dopuna 16 07 Petak 1 Dupla Prvo Poluvreme-Kraj Ukupno Golova STAR BET Peru 2 Šansa Poluvreme 2+ 1 X 2 1X 12 X2 1-1 X-1 X-X X-2 2-2 1 X 2 0-2 2-3 3+ 4+ 5+ R ? 1P

Dupla Prvo Poluvreme-kraj Ukupno golova STAR BETFriendly Club Matches (2x45min. or 2x40min) šansa poluvreme 2+ 1 X 2 1X 12 X2 1-1 X-1 X-X X-2 2-2 1 X 2 0-2 2-3 3+ 4+ 5+ R ? 1p. Pet 10:00 6200 III Keruleti TUE 1.21 6.00 7.50 BVSC-Zuglo - 1.03 3.30 1.63 4.65 12.0 19.0 12.5 1.50 3.15 5.85 1.50 4.40 2.85 1.12 1.42 1.89 Pet 12:00 6708 HB Koge 2.65 3.55 2.19 Helsingor 1.48 1.17 1.33 4.20 6.75 6.00 5.90 3.40 3.05 2.25 2.65 2.17 2.15 1.97 1.53 2.40 4.20 Pet 13:00 6709 Jahn Regensburg 2.06 3.60 2.90 Liberec 1.29 1.18 1.57 3.20 5.65 6.25 7.25 4.65 2.55 2.30 3.30 2.17 2.19 1.98 1.53 2.40 4.35 Pet 14:00 6710 Sigma Olomouc 1.76 3.55 3.80 Arka Gdynia 1.16 1.19 1.81 2.70 4.80 5.75 9.00 6.25 2.30 2.19 4.20 2.45 1.87 1.90 1.74 2.90 5.80 Pet 15:00 6711 Slavia P. 1.35 4.65 6.00 Piast Gliwice 1.03 1.08 2.60 1.91 4.35 8.00 14.25 10.25 1.72 2.60 5.45 1.93 2.55 2.11 1.37 2.02 3.20 Pet 15:00 6719 Vaduz 10.75 6.25 1.15 Freiburg 3.90 1.02 1.09 18.25 23.0 10.75 4.15 1.55 7.75 2.90 1.46 1.79 2.90 2.25 1.29 1.81 2.75 Pet 17:00 6712 Podbrezova 1.58 4.15 4.25 Petrzalka 1.12 1.13 2.06 2.30 4.85 7.50 10.5 6.75 2.01 2.50 4.25 1.94 2.60 2.12 1.38 2.01 3.40 Pet 17:00 6720 FK Rostov 1.78 3.55 3.65 Beitar J. -

Esports Gaming: Competing, Leveling up & Winning Minds & Wallets

Esports Gaming: Competing, Leveling Up & Winning Minds & Wallets A Consumer Insights Perspective to Esports Gaming Table of Contents 2 Overview Esports Gaming Awareness & Consideration 3 KPIs 4 6 Engagement Monetization Advocacy 12 17 24 Future Outlook Actionable Methodology 26 Recommendations 30 29 Overview 3 What is Esports? Why should I care? Four groups of professionals will gain the most strategic and actionable value from this study, including: Wikipedia defines Esports as organized, multiplayer video game competitions. Common Esports genres include real-time strategy • Production: Anyone who is involved in the production (with (RTS), fighting, first-person shooter (FPS), and multi-player online job titles such as Producer, Product Manager, etc) of gaming battle arena (MOBA.) content. • Publishing (with job titles such as Marketing, PR, Promoter, Per Newzoo, Esports generated global revenue of roughly $500M in etc.) of Esports gaming content/events 2016, 70%+ of which coming by way of advertising and sponsorship (by traditional video game companies seeking to grow their • Brands & Marketers interested in marketing to Esports audiences and revenues, and by marketers of Consumer Packaged gamers products such as Consumer Packaged Goods, Goods, Food & Beverage, Apparel and Consumer Technology). computing, electronics, clothing/apparel, food/beverage, etc. Global revenue is expected to exceed $1.5B by 2020, according to the BizReport. • Investors (either external private equity, hedge fund managers or venture capitalists; or Publisher-internal corporate/business Who should read this study? development professionals) currently considering investing in, or in the midst of an active merger/acquisition of a 3rd-party game This visual study seeks to bring clarity and understanding to the developer or publisher. -

Esports Marketer's Training Mode

ESPORTS MARKETER’S TRAINING MODE Understand the landscape Know the big names Find a place for your brand INTRODUCTION The esports scene is a marketer’s dream. Esports is a young industry, giving brands tons of opportunities to carve out a TABLE OF CONTENTS unique position. Esports fans are a tech-savvy demographic: young cord-cutters with lots of disposable income and high brand loyalty. Esports’ skyrocketing popularity means that an investment today can turn seri- 03 28 ous dividends by next month, much less next year. Landscapes Definitions Games Demographics Those strengths, however, are balanced by risk. Esports is a young industry, making it hard to navigate. Esports fans are a tech-savvy demographic: keyed in to the “tricks” brands use to sway them. 09 32 Streamers Conclusion Esports’ skyrocketing popularity is unstable, and a new Fortnite could be right Streamers around the corner. Channels Marketing Opportunities These complications make esports marketing look like a high-risk, high-reward proposition. But it doesn’t have to be. CHARGE is here to help you understand and navigate this young industry. Which games are the safest bets? Should you focus on live 18 Competitions events or streaming? What is casting, even? Competitions Teams Keep reading. Sponsors Marketing Opportunities 2 LANDSCAPE LANDSCAPE: GAMES To begin to understand esports, the tra- game Fortnite and first-person shooter Those gains are impressive, but all signs ditional sports industry is a great place game Call of Duty view themselves very point to the fact that esports will enjoy even to start. The sports industry covers a differently. -

Allt Om Dreamhack Masters Malmö

Allt om DreamHack Masters Malmö Det har blivit dags för den största internationella arenaturneringen i e-sport som hittills har arrangerats i Sverige – DreamHack Masters Malmö. Spelet är Counter Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO) och de 16 lag som göra upp om prispotten motsvarande 2 miljoner kronor, tillhör den absoluta världseliten. Här ger vi dig allt du behöver veta om turneringen, lagen, schemat och spelet. Om turneringen Turneringen inleds med gruppspel som kommer spelas mellan den 12 - 14 april. Två lag kvalificerar vidare från varje grupp till slutspelet. Gruppspelen sänds via dreamhack.tv. Lördagen den 16 april klockan 10 öppnas dörrarna till Malmö Arena för den 10 000 människor stora publiken, då två dagars spänning kan väntas enda fram till den rafflande finalen på söndagskvällen. Totalt väntas miljoner människor följa turneringen via dreamhack.tv. Önskar ni pressackreditering, skicka ett mail till [email protected] med ert namn, media ni arbetar för och kontaktuppgifter. För fler bilder: flickr.com/photos/dreamhack Fotografens namn hittar ni i fotolänken. Vanligast är Adela Sznajder eller Sebastian Ekman. Bilder från DreamHack Masters Malmö kommer kontinuerligt att läggas upp. Fotografer på plats: Adela Sznajder och Abraham Engelmark För citat, Kontakta Christian Lord, head of eSports, Dreamhack Tel. +46 70 27 50 558 och mail: [email protected] Om lagen Åtta lag har specialinbjudits till turneringen. Astralis: Danmarks bästa lag och rankad fyra i världen. Astralis väckte uppmärksamhet i dansk press när de erhöll en investering på sju miljoner danska kronor från Sunstone Capital och den danska entreprenören Tommy Ahlers, i samband med bildningen av den nya organisationen 2016. -

Counter Logic Gaming Names Weldon Green League of Legends Head Coach

Counter Logic Gaming Names Weldon Green League Of Legends Head Coach November 1, 2018 NEW YORK, Nov. 01, 2018 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Counter Logic Gaming (CLG) announced today that Weldon Green has been named head coach for the organization’s League of Legends team on a multi-year agreement. Green, a championship-winning sport psychology trainer and assistant coach in both the North American and European League Championship Series, most recently served as the Chief Executive Officer of Mind GamesConsulting, a company he founded that focuses on high-performance coaching for esports athletes, coaches and executives. “Weldon brings with him a deep understanding of how a winning culture is created for a League of Legends team – his resume, which includes four LCS titles, speaks for itself,” said Nick Allen, COO Counter Logic Gaming. “His vision, strong leadership and effective communication will be invaluable assets as we compete for the championship.” “When I started my career in esports as a professional coach and sports psychology trainer, it was with CLG,” said Green. “Now, it almost feels like I'm completing a circle and coming back home to CLG. My primary goal for the League of Legends team is to first and foremost retake the title. I’m excited to be here at CLG and just want to let our fans know: the faithful shall be rewarded.” Green, a native of Minnesota, has been part of two NA LCS championship teams, in 2015 with CLG, and in 2016 with TSM; and two European Union LCS championship teams, both in 2017 with G2. He has a master’s degree in sports science, sport, and exercise psychology from the University of Jyvaskyla in Finland, and a bachelor of arts in math and English from St.