Surname Regions and Dialectal Variation in the Asturian Linguistic Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basque Studies

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1537-2464 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Basque Literature Series launched at Frankfurt Book Fair FALL Reported by Mari Jose Olaziregi director of Literature across Frontiers, an 2004 organization that promotes literature written An Anthology of Basque Short Stories, the in minority languages in Europe. first publication in the Basque Literature Series published by the Center for NUMBER 70 Basque Studies, was presented at the Frankfurt Book Fair October 19–23. The Basque Editors’ Association / Euskal Editoreen Elkartea invited the In this issue: book’s compiler, Mari Jose Olaziregi, and two contributors, Iban Zaldua and Lourdes Oñederra, to launch the Basque Literature Series 1 book in Frankfurt. The Basque Government’s Minister of Culture, Boise Basques 2 Miren Azkarate, was also present to Kepa Junkera at UNR 3 give an introductory talk, followed by Olatz Osa of the Basque Editors’ Jauregui Archive 4 Association, who praised the project. Kirmen Uribe performs Euskal Telebista (Basque Television) 5 was present to record the event and Highlights 6 interview the participants for their evening news program. (from left) Lourdes Oñederra, Iban Zaldua, and Basque Country Tour 7 Mari Jose Olaziregi at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Research awards 9 Prof. Olaziregi explained to the [photo courtesy of I. Zaldua] group that the aim of the series, Ikasi 2005 10 consisting of literary works translated The following day the group attended the Studies Abroad in directly from Basque to English, is “to Fair, where Ms. Olaziregi met with editors promote Basque literature abroad and to and distributors to present the anthology and the Basque Country 11 cross linguistic and cultural borders in order discuss the series. -

Temperature Variability in the Bay of Biscay During the Past 40 Years, from an in Situ Analysis and a 3D Global Simulation

ARTICLE IN PRESS Continental Shelf Research 29 (2009) 1070–1087 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Continental Shelf Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/csr Temperature variability in the Bay of Biscay during the past 40 years, from an in situ analysis and a 3D global simulation S. Michel a,Ã, A.-M. Treguier b, F. Vandermeirsch a a Dynamiques de l’Environnement Coˆtier/Physique Hydrodynamique et Se´dimentaire, IFREMER, BP 70, 29280 Plouzane´, France b Laboratoire de Physique des Oce´ans, CNRS-IFREMER-IRD-UBO, BP 70, 29280 Plouzane´, France article info abstract Article history: A global in situ analysis and a global ocean simulation are used jointly to study interannual to decadal Received 21 June 2008 variability of temperature in the Bay of Biscay, from 1965 to 2003. A strong cooling is obtained at all Received in revised form depths until the mid-1970’s, followed by a sustained warming over 30 years. Strong interannual 21 November 2008 fluctuations are superimposed on this slow evolution. The fluctuations are intensified at the surface and Accepted 27 November 2008 are weakest at 500 m. A good agreement is found between the observed and simulated temperatures, Available online 6 February 2009 in terms of mean values, interannual variability and time correlations. Only the decadal trend is Keywords: significantly underestimated in the simulation. A comparison to satellite sea surface temperature (SST) Bay of Biscay data over the last 20 years is also presented. The first mode of interannual variability exhibits a quasi- Interannual temperature variability uniform structure and is related to the inverse winter North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) index. -

Class Book the World Around Us

social social PRIMARY sciences PRIMARY 6 sciencesClass Book 1 1 The world around us 2 2 3 3 Think Do Learn Social Sciences is a new series aimed at teaching content in English with a hands-on approach. This new methodology activates critical-thinking skills and helps children understand and learn in a more stimulating way. Level 6 includes extensive audio activities and a complete digital resource pack for both student and teacher. The course is completely modular, allowing for a variety of teaching situations. 9 788467 392173 6 TDL_social_sciences_6_M_cover.indd 2-3 22/04/15 15:04 social sciences 6 Module 1 The world around us 001_003__SS6PRI_Contents_M1.indd 1 24/04/15 09:39 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in Spain by Oxford University Press España S.A. Parque Empresarial San Fernando, Edificio Atenas 28830 San Fernando de Henares, Madrid, Spain © of the text: Iria Cerviño Orge, Shane Swift, 2015 © of this edition: Oxford University Press España S.A., 2015 The moral rights of the author have been asserted All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press España S.A., or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

Chapter 24. the BAY of BISCAY: the ENCOUNTERING of the OCEAN and the SHELF (18B,E)

Chapter 24. THE BAY OF BISCAY: THE ENCOUNTERING OF THE OCEAN AND THE SHELF (18b,E) ALICIA LAVIN, LUIS VALDES, FRANCISCO SANCHEZ, PABLO ABAUNZA Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO) ANDRE FOREST, JEAN BOUCHER, PASCAL LAZURE, ANNE-MARIE JEGOU Institut Français de Recherche pour l’Exploitation de la MER (IFREMER) Contents 1. Introduction 2. Geography of the Bay of Biscay 3. Hydrography 4. Biology of the Pelagic Ecosystem 5. Biology of Fishes and Main Fisheries 6. Changes and risks to the Bay of Biscay Marine Ecosystem 7. Concluding remarks Bibliography 1. Introduction The Bay of Biscay is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean, indenting the coast of W Europe from NW France (Offshore of Brittany) to NW Spain (Galicia). Tradition- ally the southern limit is considered to be Cape Ortegal in NW Spain, but in this contribution we follow the criterion of other authors (i.e. Sánchez and Olaso, 2004) that extends the southern limit up to Cape Finisterre, at 43∞ N latitude, in order to get a more consistent analysis of oceanographic, geomorphological and biological characteristics observed in the bay. The Bay of Biscay forms a fairly regular curve, broken on the French coast by the estuaries of the rivers (i.e. Loire and Gironde). The southeastern shore is straight and sandy whereas the Spanish coast is rugged and its northwest part is characterized by many large V-shaped coastal inlets (rias) (Evans and Prego, 2003). The area has been identified as a unit since Roman times, when it was called Sinus Aquitanicus, Sinus Cantabricus or Cantaber Oceanus. The coast has been inhabited since prehistoric times and nowadays the region supports an important population (Valdés and Lavín, 2002) with various noteworthy commercial and fishing ports (i.e. -

Bay of Biscay Purse Seine Sardine Fishery

Bay of Biscay purse seine sardine fishery Final Report V1 December 2016 Client Group: OPEGUI & OPESCAYA Fishermen: COFRADIA SAN MARTIN DE LAREDO FEDERACIÓN COFRADÍAS PESCADORES DE GIPUZKOA FEDERACIÓN COFRADÍAS DE PESCADORES BIZKAIA BUREAU VERITAS IBERIA SPAIN Autors : Macarena García Silva Luis Ambrosio Lisa Borges Mike Pawson Table of contents Glossary................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 6 2. Authorship and Peer Reviewers ..................................................................................... 8 The Peer Reviewers ........................................................................................................ 10 3. Description of the Fishery ............................................................................................ 11 3.1 Unit of Certification and scope of certification sought......................................... 11 3.2 Overview of the fishery ...................................................................................... 14 3.3 Principle One: Target Species Background ....................................................... 15 3.3.1 Spawning and growth ........................................................................................ 15 3.3.2 Stock assessment & status ............................................................................... 16 3.3.3 History -

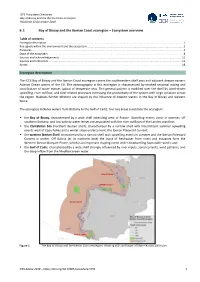

Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Coast Ecoregion Published 10 December 2020

ICES Ecosystem Overviews Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Coast ecoregion Published 10 December 2020 6.1 Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Coast ecoregion – Ecosystem Overview Table of contents Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Coast ecoregion – Ecosystem Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Ecoregion description ................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Key signals within the environment and the ecosystem .............................................................................................................................. 2 Pressures ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Climate change impacts ................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 State of the ecosystem ................................................................................................................................................................................. 9 Sources and acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................................ 14 Sources -

Port Towns and the Control of River and Maritime Zones in the Middle Ages : a Comparative Study Between Western France and Northern Castile1

Port towns and the control of river and maritime zones in the Middle Ages : a comparative study between western France and northern Castile1 by Pr. Michel Bochaca, University of La Rochelle - Dr. Beatriz Arízaga Bolumburu, University of Cantabria Dr. Alain Gallicé, University of Nantes - Dr Mathias Tranchant, University of La Rochelle This study endeavours to analyse the manner in which, during the Early Middle Ages, the main port towns along a vast section of the Atlantic coast of Europe running from Cantabria to southern Brittany organised and controlled their related river and maritime zones within a radius of varying scope (fig. 1). It will focus less on the commercial and financial influence exerted by these towns and more on the means used by their municipalities to consolidate and develop this economic hegemony such as police/legal powers as well as taxes and relations with the supervisory authorities, whether seigniorial or royal. Another aim of the comparative approach is to identify the methods and insights which can be transposed to larger geographical scales. 1. Contrasted coastal and port geography from the mouth of the Deva River to the Breton straits 1.1. Coastlines with marked physical characteristics Without erring into reductive geographical determinism, it can be considered that natural elements have greatly impacted the conditions for development of ports along the coastlines being studied. From the mouth of the Deva River up to Biarritz (Cantabria, Biscay, Guipúzcoa and the south of Labourd), the coastline is largely rocky, elevated and irregular. But although this sheer ruggedness may seem less than conducive to human activities, if we look closer, we can see that this same coastline is indented by a number of stunning bays and estuaries (or rias) which offer safe natural havens. -

Asturias (Northern Spain) As Case Study

Celts, Collective Identity and Archaeological Responsibility: Asturias (Northern Spain) as case study David González Álvarez, Carlos Marín Suárez Abstract Celtism was introduced in Asturias (Northern Spain) as a source of identity in the 19th century by the bourgeois and intellectual elite which developed the Asturianism and a regionalist political agenda. The archaeological Celts did not appear until Franco dictatorship, when they were linked to the Iron Age hillforts. Since the beginning of Spanish democracy, in 1978, most of the archaeologists who have been working on Asturian Iron Age have omit- ted ethnic studies. Today, almost nobody speaks about Celts in Academia. But, in the last years the Celtism has widespread on Asturian society. Celts are a very important political reference point in the new frame of Autonomous regions in Spain. In this context, archaeologists must to assume our responsibility in order of clarifying the uses and abuses of Celtism as a historiographical myth. We have to transmit the deconstruction of Celtism to society and we should be able to present alternatives to these archaeological old discourses in which Celtism entail the assumption of an ethnocentric, hierarchical and androcentric view of the past. Zusammenfassung Der Keltizismus wurde in Asturien (Nordspanien) als identitätsstiftende Ressource im 19. Jahrhundert durch bürgerliche und intellektuelle Eliten entwickelt, die Asturianismus und regionalistische politische Ziele propagierte. Die archäologischen Kelten erschienen allerdings erst während der Franco-Diktatur, während der sie mit den eisen- zeitlichen befestigten Höhensiedlungen verknüpft wurden. Seit der Einführung der Demokratie in Spanien im Jahr 1978 haben die meisten Archäologen, die über die asturische Eisenzeit arbeiten, ethnische Studien vernachlässigt. -

FIFG 2000–2006 Shadow Evaluation

FIFG 2000–2006 Shadow Evaluation FINAL REPORT For Pew Environment Group MARCH 2010 MAIN OFFICE: TELEPHONE: +44 1590 610168 WINDRUSH, WARBORNE LANE FAX: +44 1590 636585 PORTMORE, LYMINGTON [email protected] HAMPSHIRE SO41 5RJ http://www.consult-poseidon.com UNITED KINGDOM 610-ECE FIFG 2000-2006 Shadow Evaluation Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................................I 1 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................1 1.1 EVOLUTION OF THE FIFG STRUCTURAL FUND .....................................................................1 1.2 OBJECTIVES OF THIS REPORT ....................................................................................................3 1.3 REPORT STRUCTURE ...................................................................................................................4 2 APPROACH TO THIS EVALUATION ................................................................ 5 2.1 OVERALL APPROACH .................................................................................................................5 2.2 SCOPE ...........................................................................................................................................5 2.3 INFORMATION SOURCES............................................................................................................6 2.4 ASSUMPTIONS..............................................................................................................................7 -

Costas Del Castellano

Study Abroad Christine Tsai samples the linguistic delights of Spain’s northern and eastern coastal regions Costas del Castellano Cantabria Galicia Located on the northern coast of Spain, Cantabria is bordered Galicia, in the top left corner of by El País Vasco on the east and Castilla y León on the south. Spain, looks out over the Atlantic Cantabria belongs to Green Spain, which is the strip of land between Ocean and has more than 2,000 years the Cantabrian Sea and the Cantabrian Mountains with a moist, ocean- of history. Each year, walkers and cyclists ic climate and lush vegetation. As well as the lively capital city of travel to Galicia to make the capital, Santander, Cantabria offers quiet scenic country. Students can explore Santiago de Compostela, their destination as caves, marvel at the religious architecture, or attend one of the many they embark on the famous “Camino de Santiago,” fairs and festivals of Cantabria, filled with traditional Cantabrian music, just as pilgrims have done for the last 1,000 years. The pilgrimage con- delicious local delicacies, and exquisite handmade crafts. sists of various routes, all of which lead to St. James the Apostle at the Fundación Comillas, located close to Santander in Comillas, sur- magnificent cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. The city, which was rounded by mountains and beaches, is housed in an impressive histori- named a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1993, offers countless histori- cal 19th century building, entirely renovated and equipped with the lat- cal sites that have contributed to the city’s rich culture. -

Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Coast Ecoregion – Ecosystem Overview

ICES Ecosystem Overviews Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Coast ecoregion Published 12 December 2019 6.1 Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Coast ecoregion – Ecosystem overview Table of contents Ecoregion description ................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Key signals within the environment and the ecosystem .............................................................................................................................. 2 Pressures ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 State of the ecosystem ................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Sources and acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................................ 12 Sources and references .............................................................................................................................................................................. 13 Annex ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

The Basques by Julio Caro Baroja

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 5 The Basques by Julio Caro Baroja Translated by Kristin Addis Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 5 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2009 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Cover and series design © 2009 by Jose Luis Agote. Cover illustration: Fue painting by Julio Caro Baroja Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Caro Baroja, Julio. [Vascos. English] The Basques / by Julio Caro Baroja ; translated by Kristin Addis. p. cm. -- (Basque classics series ; no. 5) Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “The first English edition of the author’s 1949 classic on the Basque people, customs, and culture. Translation of the 1971 edition”-- Provided by publisher. *4#/ QCL ISBN 978-1-877802-92-8 (hardcover) 1. Basques--History. 2. Basques--Social life and customs. i. Title. ii. Series. GN549.B3C3713 2009 305.89’992--dc22 2009045828 Table of Contents Note on Basque Orthography.................................... vii Introduction to the First English Edition by William A. Douglass....................................... ix Preface .......................................................... 5 Introduction..................................................... 7 Part I 1. Types of Town Typical of the Basque Country: Structure of the Settlements of the Basque-Speaking Region and of the Central and Southern Areas of Araba and Navarre.......