Use and Misuse of Presidential Clemency Power for Executive Branch Officials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Profitable and Untethered March to Global Resource Dominance!

Athens Journal of Business and Economics X Y GlencoreXstrata… The Profitable and Untethered March to Global Resource Dominance! By Nina Aversano Titos Ritsatos† Motivated by the economic causes and effects of their merger in 2013, we study the expansion strategy deployment of Glencore International plc. and Xstrata plc., before and after their merger. While both companies went through a series of international acquisitions during the last decade, their merger is strengthening effective vertical integration in critical resource and commodity markets, following Hymer’s theory of internationalization and Dunning’s theory of Eclectic Paradigm. Private existence of global dominant positioning in vital resource markets, posits economic sustainability and social fairness questions on an international scale. Glencore is alleged to have used unethical business tactics, increasing corruption, tax evasion and money laundering, while attracting the attention of human rights organizations. Since the announcement of their intended merger, the company’s market performance has been lower than its benchmark index. Glencore’s and Xstrata’s economic success came from operating effectively and efficiently in markets that scare off risk-averse companies. The new GlencoreXstrata is not the same company anymore. The Company’s new capital structure is characterized by controlling presence of institutional investors, creating adherence to corporate governance and increased monitoring and transparency. Furthermore, when multinational corporations like GlencoreXstrata increase in size attracting the attention of global regulation, they are forced by institutional monitoring to increase social consciousness. When ensuring full commitment to social consciousness acting with utmost concern with regard to their commitment by upholding rules and regulations of their home or host country, they have but to become “quasi-utilities” for the global industry. -

Foreignpolicyleopold

Foreign Policy VOICE The 750 Million Dollar Man How a Swiss commodities giant used shell companies to make an Angolan general three-quarters of a billion dollars richer. BY Michael Weiss FEBRUARY 13, 2014 Revolutionary communist regimes have a strange habit of transforming themselves into corrupt crony capitalist ones and Angola -- with its massive oil reserves and budding crop of billionaires -- has proved no exception. In 2010, Trafigura, the world’s third-largest private oil and metals trader based in Switzerland, sold an 18.75-percent stake in one of its major energy subsidiaries to a high-ranking and influential Angolan general, Foreign Policy has discovered. The sale, which amounted to $213 million, appears on the 2012 audit of the annual financial statements of a Singapore-registered company, which is wholly owned by Gen. Leopoldino Fragoso do Nascimento. Details of the sale and purchaser are also buried within a prospectus document of the sold company which was uploaded to the Luxembourg Stock Exchange within the last week. “General Dino,” as he’s more commonly called in Angola, purchased the 18.75 percent stake not in any minor bauble, but in a $5 billion multinational oil company called Puma Energy International. By 2011, his shares were diluted to 15 percent; but that’s still quite a hefty prize: his stake in the company is today valued at around $750 million. The sale illuminates not only a growing and little-scrutinized relationship between Trafigura, which earned nearly $1 billion in profits in 2012, and the autocratic regime of 71-year-old Angolan President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who has been in power since 1979 -- but also the role that Western enterprise continues to play in the Third World. -

GLENCORE: a Guide to the 'Biggest Company You've Never Heard

GLENCORE: a guide to the ‘biggest company you’ve never heard of’ WHO IS GLENCORE? Glencore is the world’s biggest commodities trading company and 16th largest company in the world according to Fortune 500. When it went public, it controlled 60% of the zinc market, 50% of the trade in copper, 45% of lead and a third of traded aluminium and thermal coal. On top of that, Glencore also trades oil, gas and basic foodstuffs like grain, rice and sugar. Sometimes refered to as ‘the biggest company you’ve never heard of’, Glencore’s reach is so vast that almost every person on the planet will come into contact with products traded by Glencore, via the minerals in cell phones, computers, cars, trains, planes and even the grains in meals or the sugar in drinks. It’s not just a trader: Glencore also produces and extracts these commodities. It owns significant mining interests, and in Democratic Republic of Congo it has two of the country’s biggest copper and cobalt operations, called KCC and MUMI. Glencore listed on the London Stock Exchange in 2011 in what is still the biggest ever Initial Public Offering (IPO) in the stock exchange’s history, with a valuation of £36bn. Glencore started life as Marc Rich & Co AG, set up by the eponymous and notorious commodities trader in 1974. In 1983 Rich was charged in the US with massive tax evasion and trading with Iran. He fled to Switzerland and lived in exile while on the FBI's most-wanted list for nearly two decades. -

Chapter 48 – Creative Destructor

Chapter 48 Creative destructor Starting in the late 19th century, when the Hall-Heroult electrolytic reduction process made it possible for aluminum to be produced as a commodity, aluminum companies began to consolidate and secure raw material sources. Alcoa led the way, acquiring and building hydroelectric facilities, bauxite mines, alumina refineries, aluminum smelters, fabricating plants and even advanced research laboratories to develop more efficient processing technologies and new products. The vertical integration model was similar to the organizing system used by petroleum companies, which explored and drilled for oil, built pipelines and ships to transport oil, owned refineries that turned oil into gasoline and other products, and even set up retail outlets around the world to sell their products. The global economy dramatically changed after World War II, as former colonies with raw materials needed by developed countries began to ask for a piece of the action. At the same time, more corporations with the financial and technical means to enter at least one phase of aluminum production began to compete in the marketplace. As the global Big 6 oligopoly became challenged on multiple fronts, a commodity broker with a Machiavellian philosophy and a natural instinct for deal- making smelled blood and started picking the system apart. Marc Rich began by taking advantage of the oil market, out-foxing the petroleum giants and making a killing during the energy crises of the 1970s. A long-time metals trader, Rich next eyed the weakened aluminum industry during the 1980s, when depressed demand and over-capacity collided with rising energy costs, according to Shawn Tully’s 1988 account in Fortune. -

Metal Men Metal Men Marc Rich and the $10 Billion Scam A

Metal Men Metal Men Marc Rich and the $10 Billion Scam A. Craig Copetas No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, scanning or any information storage retrieval system, without explicit permission in writing from the Author. © Copyright 1985 by A. Craig Copetas First e-reads publication 1999 www.e-reads.com ISBN 0-7592-3859-6 for B.D. Don Erickson & Margaret Sagan Acknowledgments [ e - reads] Acknowledgments o those individual traders around the world who allowed me to con- duct deals under their supervision so that I could better grasp the trader’s life, I thank you for trusting me to handle your business Tactivities with discretion. Many of those traders who helped me most have no desire to be thanked. They were usually the most helpful. So thank you anyway. You know who you are. Among those both inside and outside the international commodity trad- ing profession who did help, my sincere gratitude goes to Robert Karl Manoff, Lee Mason, James Horwitz, Grainne James, Constance Sayre, Gerry Joe Goldstein, Christine Goldstein, David Noonan, Susan Faiola, Gary Redmore, Ellen Hume, Terry O’Neil, Calliope, Alan Flacks, Hank Fisher, Ernie Torriero, Gordon “Mr. Rhodium” Davidson, Steve Bronis, Jan Bronis, Steve Shipman, Henry Rothschild, David Tendler, John Leese, Dan Baum, Bert Rubin, Ernie Byle, Steven English and the Cobalt Cartel, Michael Buchter, Peter Marshall, Herve Kelecom, Misha, Mark Heutlinger, Bonnie Cutler, John and Galina Mariani, Bennie (Bollag) and his Jets, Fredy Haemmerli, Wil Oosterhout, Christopher Dark, Eddie de Werk, Hubert Hutton, Fred Schwartz, Ira Sloan, Frank Wolstencroft, Congressman James Santini, John Culkin, Urs Aeby, Lynn Grebstad, Intertech Resources, the Kaypro Corporation, Harper’s magazine, Cambridge Metals, Redco v Acknowledgments [ e - reads] Resources, the Swire Group, ITR International, Philipp Brothers, the Heavy Metal Kids, and . -

Glencore: Notorious Crimes and Failures

Glencore: Notorious crimes and failures Mining giant Glencore has made aggressive use Presence: 50+ countries of complex corporate structure and tax havens Number of employees: 155.000 (2016)5 to deprive developing nations of tax revenues, while frequently being accused of human and Company activity environmental rights violations in the course of Main activities: production, sourcing, processing, refining, its business. transporting, storage, financing and supply of metals and minerals, energy products and agricultural products. Problem Analysis Country and location in which Swiss mining giant Glencore has made extensive efforts to exploit corporate power for its own advantage, often the violation occurred at the expense of human and environmental rights. It has As Glencore owns over 150 mining & metallurgical, oil made use of Investor–State dispute mechanisms when production and agricultural assets around the world, there governments have restricted its activity. It has adopted are many different countries involved and affected. a complex international structure to minimise its tax Ghana, Chad, Zambia, Bolivia, Colombia, Philippines, exposure and so deprived a number of developing nations Argentina etc.7 of tax revenues, including Zambia and Burkina Faso. It has been accused of causing human rights violations and Summary of the case environmental damage at mining operations as far afield as Response of Glencore to several of these issues http:// Peru and Australia. www.glencore.com/assets/public-positions/doc/ Company Glencores-response-to-the-2015-Public-Eye-Nomination. pdf & http://www.glencore.com/public-positions Main Company: Glencore plc. 1. ISDS cases Head office: Baar, Switzerland In 2016, Glencore initiated two ISDS (Investor State Registered office: Saint Helier, Jersey Dispute Settlement) cases. -

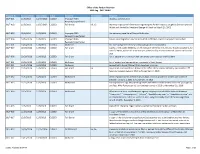

2017 and 2018 Source File from IQ

Office of the Pardon Attorney FOIA Log - 2017 DRAFT Request No. Received Date Closed Date Status Outcome Exemptions Request 2017-001 11/8/2016 11/25/2016 CLOSED Improper FOIA requests commutation Request/Unperfected 2017-002 11/8/2016 11/25/2016 CLOSED Full Denial b6, b5 Attorney request for information regarding the Pardon request sought by Bernard Donald Miskiv and denied by President George W. Bush on March 20, 2002 2017-003 10/4/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED Improper FOIA the clemency case file of Damon Burkhalter Request/Unperfected 2017-004 10/18/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED Improper FOIA advice on immigration issue as a result of ineffective counsel and police misconduct Request/Unperfected 2017-006 10/18/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED No Record the race and gender of these individuals granted commutation 2017-007 10/20/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED Full Grant copies of the public elements of the executive clemency file and any related documents for Danielle Metz, whose life sentence was commuted by President Barack Obama earlier this year 2017-008 10/28/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED Full Grant list of people who have had their sentences commuted by the President 2017-009 10/28/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED No Record list of pardon and commutation recipients in Excel format 2017-010 11/11/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED No Record requesting to know if Robert Gallo received a pardon 2017-011 11/14/2016 12/9/2016 CLOSED Full Grant b6 any and all correspondence between the Office of the Pardon Attorney and Senator Jeff Sessions between January 2010 to November 14, 2016 2017-012 11/14/2016 12/9/2016 CLOSED No Record all correspondence to or from Rudy Giuliani or correspondence written on his behalf between January 1, 2001 to November 14, 2016 2017-013 11/21/2016 12/9/2016 CLOSED No Record correspondence logs documenting letters and other communication between your agency and Rep. -

THE BIGGEST COMPANY YOU NEVER HEARD of a Powerful and Secretive Swiss Trader Is Likely to List This Year

REUTERS/ CHRIstIAN HArtMANN THE BIGGEST COMPANY YOU NEVER HEARD OF A powerful and secretive Swiss trader is likely to list this year. Can the Goldman Sachs of commodity trading survive going public? BY ERIC ONstAD, LAURA MACINNIS AND six months and was running out of cash. months, and Congo -- still struggling to QUENTIN WEBB Needing to finance its mining projects in the recover from a civil war that killed some BAAR, SWITZERLAND, FEB. 25 Democratic Republic of Congo -- a country five million people – was the last place an which has some of the world’s richest investor wanted to be. n Christmas Eve 2008, in the depths reserves of copper and cobalt -- Katanga’s One company, though, was interested. of the global financial crisis, Katanga executives had sounded the alarm and made Executives in the wealthy Swiss village MiningO accepted a lifeline it could not refuse. a string of calls for help. of Baar, working in the wood-panelled The Toronto-listed company had lost 97 Global credit was drying up, the copper conference rooms in Glencore International’s percent of its market value over the previous market had fallen 70 percent in just five white metallic headquarters, did their sums FEBRUARY 2011 GLENcore FebruARY 2011 and were prepared to make a deal. Their often brilliant, its staff dominate their market. and Royal Dutch Shell and from there into the terms were simple. The firm’s top executives have forged alliances pension funds and investment portfolios of They wanted control. with Russian oligarchs and well-connected millions of people who know virtually nothing For about $500 million in a convertible African mining magnates. -

President's Report 2018

VISION COUNTING UP TO 50 President's Report 2018 Chairman’s Message 4 President’s Message 5 Senior Administration 6 BGU by the Numbers 8 Building BGU 14 Innovation for the Startup Nation 16 New & Noteworthy 20 From BGU to the World 40 President's Report Alumni Community 42 2018 Campus Life 46 Community Outreach 52 Recognizing Our Friends 57 Honorary Degrees 88 Board of Governors 93 Associates Organizations 96 BGU Nation Celebrate BGU’s role in the Israeli miracle Nurturing the Negev 12 Forging the Hi-Tech Nation 18 A Passion for Research 24 Harnessing the Desert 30 Defending the Nation 36 The Beer-Sheva Spirit 44 Cultivating Israeli Society 50 Produced by the Department of Publications and Media Relations Osnat Eitan, Director In coordination with the Department of Donor and Associates Affairs Jill Ben-Dor, Director Editor Elana Chipman Editorial Staff Ehud Zion Waldoks, Jacqueline Watson-Alloun, Angie Zamir Production Noa Fisherman Photos Dani Machlis Concept and Design www.Image2u.co.il 4 President's Report 2018 Ben-Gurion University of the Negev - BGU Nation 5 From the From the Chairman President Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben–Gurion, said:“Only Apartments Program, it is worth noting that there are 73 This year we are celebrating Israel’s 70th anniversary and Program has been studied and reproduced around through a united effort by the State … by a people ready “Open Apartments” in Beer-Sheva’s neighborhoods, where acknowledging our contributions to the State of Israel, the the world and our students are an inspiration to their for a great voluntary effort, by a youth bold in spirit and students live and actively engage with the local community Negev, and the world, even as we count up to our own neighbors, encouraging them and helping them strive for a inspired by creative heroism, by scientists liberated from the through various cultural and educational activities. -

Commodity Traders in a Storm: Financialization, Corporate Power and Ecological Crisis

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Baines, Joseph; Hager, Sandy Brian Article — Manuscript Version (Preprint) Commodity Traders in a Storm: Financialization, Corporate Power and Ecological Crisis Review of International Political Economy Provided in Cooperation with: The Bichler & Nitzan Archives Suggested Citation: Baines, Joseph; Hager, Sandy Brian (2021) : Commodity Traders in a Storm: Financialization, Corporate Power and Ecological Crisis, Review of International Political Economy, ISSN 1466-4526, Taylor & Francis, London, Iss. Latest Articles, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2021.1872039 , http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/672/ This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/229186 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 111 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 111 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 155 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, JANUARY 30, 2009 No. 19 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Monday, February 2, 2009, at 2 p.m. Senate FRIDAY, JANUARY 30, 2009 The Senate met at 9:31 a.m. and was to the Senate from the President pro RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME called to order by the Honorable MARK tempore (Mr. BYRD). The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- R. WARNER, a Senator from the Com- The assistant legislative clerk read pore. Under the previous order, the monwealth of Virginia. the following letter: leadership time is reserved. U.S. SENATE, PRAYER PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, f Washington, DC, January 30, 2009. The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- MORNING BUSINESS fered the following prayer: To the Senate: Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- Let us pray. of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby Eternal Spirit, our shelter in the pore. Under the previous order, the appoint the Honorable MARK R. WARNER, a Senate will proceed to a period for the time of storm, our rock in a weary Senator from the Commonwealth of Vir- land, Lord, we live in challenging ginia, to perform the duties of the Chair. transaction of morning business, with times that require more than human ROBERT C. BYRD, Senators permitted to speak for up to solutions for our problems. -

Riches, Clintons, and Gores, Oh My!

Riches, Clintons, and Gores, Oh My! By Chachi Bayou I’ll start by pulling apart the fake death of DNC staffer Seth Rich (above), though he will just be our diving board into myriad more interesting discoveries. Seth Rich was the (Jewish) DNC staffer who was allegedly gunned down in D.C. while walking home from a bar on July 10, 2016. The unexplained circumstances of Rich’s death and his ties to the Clintons caused the paid apes on the alt-right conspiracy forums to rattle their cages. Even Fox News peddled it for a while. The main theory was that Seth was involved with the leaked DNC emails showing that Hillary stole the democratic nomination from the more popular Bernie Sanders. The email leaks led to the ousting of (Jewish) DNC chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz and may have caused Hillary to lose the election. As the theory goes, the Clintons had Seth whacked either for revenge or in a too-late attempt to prevent the leak. The Rich story fed into the larger conspiracy theory known as the Clinton Body Count – people with close ties to the Clintons who have died under suspicious circumstances over the years. Most conspiracy theory forums are run by Intelligence, and the few that aren’t just parrot those that are. The Clinton Body Count conspiracy is pure misdirection, as usual, pushed by Intelligence to control anyone who strays from the mainstream narrative. They’ve created rabbit holes everywhere for people like you and me to fall into, and each one has a different flavor to appeal to our different tastes and biases.