The Profitable and Untethered March to Global Resource Dominance!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foreignpolicyleopold

Foreign Policy VOICE The 750 Million Dollar Man How a Swiss commodities giant used shell companies to make an Angolan general three-quarters of a billion dollars richer. BY Michael Weiss FEBRUARY 13, 2014 Revolutionary communist regimes have a strange habit of transforming themselves into corrupt crony capitalist ones and Angola -- with its massive oil reserves and budding crop of billionaires -- has proved no exception. In 2010, Trafigura, the world’s third-largest private oil and metals trader based in Switzerland, sold an 18.75-percent stake in one of its major energy subsidiaries to a high-ranking and influential Angolan general, Foreign Policy has discovered. The sale, which amounted to $213 million, appears on the 2012 audit of the annual financial statements of a Singapore-registered company, which is wholly owned by Gen. Leopoldino Fragoso do Nascimento. Details of the sale and purchaser are also buried within a prospectus document of the sold company which was uploaded to the Luxembourg Stock Exchange within the last week. “General Dino,” as he’s more commonly called in Angola, purchased the 18.75 percent stake not in any minor bauble, but in a $5 billion multinational oil company called Puma Energy International. By 2011, his shares were diluted to 15 percent; but that’s still quite a hefty prize: his stake in the company is today valued at around $750 million. The sale illuminates not only a growing and little-scrutinized relationship between Trafigura, which earned nearly $1 billion in profits in 2012, and the autocratic regime of 71-year-old Angolan President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who has been in power since 1979 -- but also the role that Western enterprise continues to play in the Third World. -

GLENCORE: a Guide to the 'Biggest Company You've Never Heard

GLENCORE: a guide to the ‘biggest company you’ve never heard of’ WHO IS GLENCORE? Glencore is the world’s biggest commodities trading company and 16th largest company in the world according to Fortune 500. When it went public, it controlled 60% of the zinc market, 50% of the trade in copper, 45% of lead and a third of traded aluminium and thermal coal. On top of that, Glencore also trades oil, gas and basic foodstuffs like grain, rice and sugar. Sometimes refered to as ‘the biggest company you’ve never heard of’, Glencore’s reach is so vast that almost every person on the planet will come into contact with products traded by Glencore, via the minerals in cell phones, computers, cars, trains, planes and even the grains in meals or the sugar in drinks. It’s not just a trader: Glencore also produces and extracts these commodities. It owns significant mining interests, and in Democratic Republic of Congo it has two of the country’s biggest copper and cobalt operations, called KCC and MUMI. Glencore listed on the London Stock Exchange in 2011 in what is still the biggest ever Initial Public Offering (IPO) in the stock exchange’s history, with a valuation of £36bn. Glencore started life as Marc Rich & Co AG, set up by the eponymous and notorious commodities trader in 1974. In 1983 Rich was charged in the US with massive tax evasion and trading with Iran. He fled to Switzerland and lived in exile while on the FBI's most-wanted list for nearly two decades. -

Chapter 48 – Creative Destructor

Chapter 48 Creative destructor Starting in the late 19th century, when the Hall-Heroult electrolytic reduction process made it possible for aluminum to be produced as a commodity, aluminum companies began to consolidate and secure raw material sources. Alcoa led the way, acquiring and building hydroelectric facilities, bauxite mines, alumina refineries, aluminum smelters, fabricating plants and even advanced research laboratories to develop more efficient processing technologies and new products. The vertical integration model was similar to the organizing system used by petroleum companies, which explored and drilled for oil, built pipelines and ships to transport oil, owned refineries that turned oil into gasoline and other products, and even set up retail outlets around the world to sell their products. The global economy dramatically changed after World War II, as former colonies with raw materials needed by developed countries began to ask for a piece of the action. At the same time, more corporations with the financial and technical means to enter at least one phase of aluminum production began to compete in the marketplace. As the global Big 6 oligopoly became challenged on multiple fronts, a commodity broker with a Machiavellian philosophy and a natural instinct for deal- making smelled blood and started picking the system apart. Marc Rich began by taking advantage of the oil market, out-foxing the petroleum giants and making a killing during the energy crises of the 1970s. A long-time metals trader, Rich next eyed the weakened aluminum industry during the 1980s, when depressed demand and over-capacity collided with rising energy costs, according to Shawn Tully’s 1988 account in Fortune. -

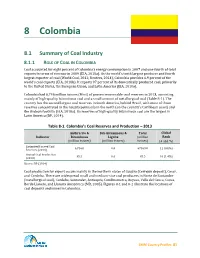

Chapter 8: Colombia

8 Colombia 8.1 Summary of Coal Industry 8.1.1 ROLE OF COAL IN COLOMBIA Coal accounted for eight percent of Colombia’s energy consumption in 2007 and one-fourth of total exports in terms of revenue in 2009 (EIA, 2010a). As the world’s tenth largest producer and fourth largest exporter of coal (World Coal, 2012; Reuters, 2014), Colombia provides 6.9 percent of the world’s coal exports (EIA, 2010b). It exports 97 percent of its domestically produced coal, primarily to the United States, the European Union, and Latin America (EIA, 2010a). Colombia had 6,746 million tonnes (Mmt) of proven recoverable coal reserves in 2013, consisting mainly of high-quality bituminous coal and a small amount of metallurgical coal (Table 8-1). The country has the second largest coal reserves in South America, behind Brazil, with most of those reserves concentrated in the Guajira peninsula in the north (on the country’s Caribbean coast) and the Andean foothills (EIA, 2010a). Its reserves of high-quality bituminous coal are the largest in Latin America (BP, 2014). Table 8-1. Colombia’s Coal Reserves and Production – 2013 Anthracite & Sub-bituminous & Total Global Indicator Bituminous Lignite (million Rank (million tonnes) (million tonnes) tonnes) (# and %) Estimated Proved Coal 6,746.0 0.0 67469.0 11 (0.8%) Reserves (2013) Annual Coal Production 85.5 0.0 85.5 10 (1.4%) (2013) Source: BP (2014) Coal production for export occurs mainly in the northern states of Guajira (Cerrejón deposit), Cesar, and Cordoba. There are widespread small and medium-size coal producers in Norte de Santander (metallurgical coal), Cordoba, Santander, Antioquia, Cundinamarca, Boyaca, Valle del Cauca, Cauca, Borde Llanero, and Llanura Amazónica (MB, 2005). -

Metal Men Metal Men Marc Rich and the $10 Billion Scam A

Metal Men Metal Men Marc Rich and the $10 Billion Scam A. Craig Copetas No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, scanning or any information storage retrieval system, without explicit permission in writing from the Author. © Copyright 1985 by A. Craig Copetas First e-reads publication 1999 www.e-reads.com ISBN 0-7592-3859-6 for B.D. Don Erickson & Margaret Sagan Acknowledgments [ e - reads] Acknowledgments o those individual traders around the world who allowed me to con- duct deals under their supervision so that I could better grasp the trader’s life, I thank you for trusting me to handle your business Tactivities with discretion. Many of those traders who helped me most have no desire to be thanked. They were usually the most helpful. So thank you anyway. You know who you are. Among those both inside and outside the international commodity trad- ing profession who did help, my sincere gratitude goes to Robert Karl Manoff, Lee Mason, James Horwitz, Grainne James, Constance Sayre, Gerry Joe Goldstein, Christine Goldstein, David Noonan, Susan Faiola, Gary Redmore, Ellen Hume, Terry O’Neil, Calliope, Alan Flacks, Hank Fisher, Ernie Torriero, Gordon “Mr. Rhodium” Davidson, Steve Bronis, Jan Bronis, Steve Shipman, Henry Rothschild, David Tendler, John Leese, Dan Baum, Bert Rubin, Ernie Byle, Steven English and the Cobalt Cartel, Michael Buchter, Peter Marshall, Herve Kelecom, Misha, Mark Heutlinger, Bonnie Cutler, John and Galina Mariani, Bennie (Bollag) and his Jets, Fredy Haemmerli, Wil Oosterhout, Christopher Dark, Eddie de Werk, Hubert Hutton, Fred Schwartz, Ira Sloan, Frank Wolstencroft, Congressman James Santini, John Culkin, Urs Aeby, Lynn Grebstad, Intertech Resources, the Kaypro Corporation, Harper’s magazine, Cambridge Metals, Redco v Acknowledgments [ e - reads] Resources, the Swire Group, ITR International, Philipp Brothers, the Heavy Metal Kids, and . -

Glencore: Notorious Crimes and Failures

Glencore: Notorious crimes and failures Mining giant Glencore has made aggressive use Presence: 50+ countries of complex corporate structure and tax havens Number of employees: 155.000 (2016)5 to deprive developing nations of tax revenues, while frequently being accused of human and Company activity environmental rights violations in the course of Main activities: production, sourcing, processing, refining, its business. transporting, storage, financing and supply of metals and minerals, energy products and agricultural products. Problem Analysis Country and location in which Swiss mining giant Glencore has made extensive efforts to exploit corporate power for its own advantage, often the violation occurred at the expense of human and environmental rights. It has As Glencore owns over 150 mining & metallurgical, oil made use of Investor–State dispute mechanisms when production and agricultural assets around the world, there governments have restricted its activity. It has adopted are many different countries involved and affected. a complex international structure to minimise its tax Ghana, Chad, Zambia, Bolivia, Colombia, Philippines, exposure and so deprived a number of developing nations Argentina etc.7 of tax revenues, including Zambia and Burkina Faso. It has been accused of causing human rights violations and Summary of the case environmental damage at mining operations as far afield as Response of Glencore to several of these issues http:// Peru and Australia. www.glencore.com/assets/public-positions/doc/ Company Glencores-response-to-the-2015-Public-Eye-Nomination. pdf & http://www.glencore.com/public-positions Main Company: Glencore plc. 1. ISDS cases Head office: Baar, Switzerland In 2016, Glencore initiated two ISDS (Investor State Registered office: Saint Helier, Jersey Dispute Settlement) cases. -

2017 and 2018 Source File from IQ

Office of the Pardon Attorney FOIA Log - 2017 DRAFT Request No. Received Date Closed Date Status Outcome Exemptions Request 2017-001 11/8/2016 11/25/2016 CLOSED Improper FOIA requests commutation Request/Unperfected 2017-002 11/8/2016 11/25/2016 CLOSED Full Denial b6, b5 Attorney request for information regarding the Pardon request sought by Bernard Donald Miskiv and denied by President George W. Bush on March 20, 2002 2017-003 10/4/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED Improper FOIA the clemency case file of Damon Burkhalter Request/Unperfected 2017-004 10/18/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED Improper FOIA advice on immigration issue as a result of ineffective counsel and police misconduct Request/Unperfected 2017-006 10/18/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED No Record the race and gender of these individuals granted commutation 2017-007 10/20/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED Full Grant copies of the public elements of the executive clemency file and any related documents for Danielle Metz, whose life sentence was commuted by President Barack Obama earlier this year 2017-008 10/28/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED Full Grant list of people who have had their sentences commuted by the President 2017-009 10/28/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED No Record list of pardon and commutation recipients in Excel format 2017-010 11/11/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED No Record requesting to know if Robert Gallo received a pardon 2017-011 11/14/2016 12/9/2016 CLOSED Full Grant b6 any and all correspondence between the Office of the Pardon Attorney and Senator Jeff Sessions between January 2010 to November 14, 2016 2017-012 11/14/2016 12/9/2016 CLOSED No Record all correspondence to or from Rudy Giuliani or correspondence written on his behalf between January 1, 2001 to November 14, 2016 2017-013 11/21/2016 12/9/2016 CLOSED No Record correspondence logs documenting letters and other communication between your agency and Rep. -

The Weir Minerals Mill Circuit Solution Optimise Operations and Minimise Downtime

THE WEIR MINERALS MILL CIRCUIT SOLUTION OPTIMISE OPERATIONS AND MINIMISE DOWNTIME motralec 4 rue Lavoisier . ZA Lavoisier . 95223 HERBLAY CEDEX Tel. : 01.39.97.65.10 / Fax. : 01.39.97.68.48 Demande de prix / e-mail : [email protected] www.motralec.com Decreasing throughput. Interrupted fl ow. Unrealised potential. When your job is to micromanage movement, your equipment must function seamlessly. You depend on each piece of your circuit to work as one. You demand reliable starts and continuous “ We view our products in the same way The Weir Minerals Mill Circuit Solution is a combination of as our customers, seeing them not in processing—anything less than swift and steady is unacceptable. fi ve performance-leading brands, each with an exceptional isolation, but as part of a chain. In doing success record. KHD® high pressure grinding rolls, Warman® pumps, this, we recognise that a chain—the Vulco® wear resistant linings, Cavex® hydrocyclones and Isogate® valves create the solution you can count on to deliver more durability, customer’s process—is only as strong as improved throughput and less downtime. You can also count on its weakest link. This philosophy ensures technically led and quality assured complete management service that we address the areas that cost the throughout the life of your operation. Why the Weir Minerals Mill Circuit Solution? customer time and money. Our specialist We know that vital factors, including water levels, play a approach to these critical applications Because you’re only as strong as your weakest link. critical role in throughput and output. Weir Minerals offers means that all our development time and Floway® vertical turbine pumps, which work seamlessly in the circuit effort ensures that we deliver maximum For more than 75 years Weir Minerals has perfected the delivery and support of mill for many types of applications. -

THE BIGGEST COMPANY YOU NEVER HEARD of a Powerful and Secretive Swiss Trader Is Likely to List This Year

REUTERS/ CHRIstIAN HArtMANN THE BIGGEST COMPANY YOU NEVER HEARD OF A powerful and secretive Swiss trader is likely to list this year. Can the Goldman Sachs of commodity trading survive going public? BY ERIC ONstAD, LAURA MACINNIS AND six months and was running out of cash. months, and Congo -- still struggling to QUENTIN WEBB Needing to finance its mining projects in the recover from a civil war that killed some BAAR, SWITZERLAND, FEB. 25 Democratic Republic of Congo -- a country five million people – was the last place an which has some of the world’s richest investor wanted to be. n Christmas Eve 2008, in the depths reserves of copper and cobalt -- Katanga’s One company, though, was interested. of the global financial crisis, Katanga executives had sounded the alarm and made Executives in the wealthy Swiss village MiningO accepted a lifeline it could not refuse. a string of calls for help. of Baar, working in the wood-panelled The Toronto-listed company had lost 97 Global credit was drying up, the copper conference rooms in Glencore International’s percent of its market value over the previous market had fallen 70 percent in just five white metallic headquarters, did their sums FEBRUARY 2011 GLENcore FebruARY 2011 and were prepared to make a deal. Their often brilliant, its staff dominate their market. and Royal Dutch Shell and from there into the terms were simple. The firm’s top executives have forged alliances pension funds and investment portfolios of They wanted control. with Russian oligarchs and well-connected millions of people who know virtually nothing For about $500 million in a convertible African mining magnates. -

A Leading Integrated Marketer and Producer of Commodities

Glencore Preliminary Results 2011 5 March 2012 Ivan Glasenberg Chief Executive Officer I 1 2011 highlights . Solid underlying profit highlighting the diversity and growth in Glencore’s businesses – Adjusted EBIT(1) up 2% to $5.4bn (Industrial up 18%, Marketing up >10% excluding Agricultural Products) – Glencore net income(1) up 7% to $4.1bn . Strong operating cash flow of $3.5bn(2) up 6% . Robust balance sheet with close to $7bn committed liquidity(3) provides security and opportunities – FFO to Net debt at 27% – S&P and Moody’s investment grade credit ratings improved in July(4) . Final dividend of $0.10 per share (total dividend of $0.15 per share) . Growth projects overall on track to time and budget Notes: (1) Pre other significant items. (2) Funds from operations. (3) Cash and undrawn committed facilities. (4) Moody’s Baa2 (stable), S&P BBB (stable). Following announcement of Xstrata merger, both agencies have flagged possible upgrade potential. I 2 2011 operating performance – Marketing activities Metals & Marketing activities delivered consistent results over 2011, generating Adjusted EBIT of $1.2bn, 11% lower than 2010 Minerals Marketed volumes were 5,652k MT Cu equivalent, 4% lower than 2010 Decline in performance partly due to lower profits from the ferroalloys and zinc/copper departments (which performed strongly in 2010 when physical purchasing and restocking in Asia was particularly intensive), offset by higher profits in the alumina/aluminium department where arbitrage opportunities were more favourable Energy Energy -

Escondida Site Tour

Escondida site tour Edgar Basto President Escondida 1 October 2012 Disclaimer Forward looking statements This presentation includes forward-looking statements within the meaning of the U.S. Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 regarding future events, conditions, circumstances and the future ffinancialinancial performance of BHP Billiton, including for capital expenditures, productionvn volumes, project capacity, and schedules for expected production. Often, but not always, forward-looking statements can be identified by the use of the words such as “plans”, “expects”, “expected”, “scheduled”, “estimates”, “intends”, “anticipates”, “believes” or variations of such words and phrases or state that certain actions, events, conditions, circumstances or results “may”, “could”, “would”, “might” or “will” be taken, occur or be achieved. These forward-looking statements are not guarantees or predictions of future performance, and involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, many of which are beyond our control, and which may cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed in the statements contained in this presentation. For more detail on those risks, you should refer to the sections of our annual report on Form 20-F for the year ended 30 June 2012 entitled “Risk factors ”, “Forward looking stateme nts” and “Operating and financial review and prospects” filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). Any estimates and projections in this presentation are illustrative only. Our actual results may be materially affected by changes in economic or other circumstances which cannot be foreseen. Nothing in this presentation is, or should be relied on as, a promise or representation either as to future results or events or as to the reasonableness of any assumption or view expressly or impliedly contained herein. -

President's Report 2018

VISION COUNTING UP TO 50 President's Report 2018 Chairman’s Message 4 President’s Message 5 Senior Administration 6 BGU by the Numbers 8 Building BGU 14 Innovation for the Startup Nation 16 New & Noteworthy 20 From BGU to the World 40 President's Report Alumni Community 42 2018 Campus Life 46 Community Outreach 52 Recognizing Our Friends 57 Honorary Degrees 88 Board of Governors 93 Associates Organizations 96 BGU Nation Celebrate BGU’s role in the Israeli miracle Nurturing the Negev 12 Forging the Hi-Tech Nation 18 A Passion for Research 24 Harnessing the Desert 30 Defending the Nation 36 The Beer-Sheva Spirit 44 Cultivating Israeli Society 50 Produced by the Department of Publications and Media Relations Osnat Eitan, Director In coordination with the Department of Donor and Associates Affairs Jill Ben-Dor, Director Editor Elana Chipman Editorial Staff Ehud Zion Waldoks, Jacqueline Watson-Alloun, Angie Zamir Production Noa Fisherman Photos Dani Machlis Concept and Design www.Image2u.co.il 4 President's Report 2018 Ben-Gurion University of the Negev - BGU Nation 5 From the From the Chairman President Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben–Gurion, said:“Only Apartments Program, it is worth noting that there are 73 This year we are celebrating Israel’s 70th anniversary and Program has been studied and reproduced around through a united effort by the State … by a people ready “Open Apartments” in Beer-Sheva’s neighborhoods, where acknowledging our contributions to the State of Israel, the the world and our students are an inspiration to their for a great voluntary effort, by a youth bold in spirit and students live and actively engage with the local community Negev, and the world, even as we count up to our own neighbors, encouraging them and helping them strive for a inspired by creative heroism, by scientists liberated from the through various cultural and educational activities.