Foreignpolicyleopold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corruption-In-Angola.Pdf

Corruption in Angola: An Impediment to Democracy Rafael Marques de Morais * * The author is currently writing a book on corruption in Angola. He has recently published a book on human rights abuses and corruption in the country’s diamond industry ( Diamantes de Sangue: Tortura e Corrupção em Angola . Tinta da China: Lisboa, 2011 ), and is developing the anti-corruption watchdog Maka Ang ola www.makaangola.org . He holds a BA in Anthropology and Media from Goldsmiths College, University of London, and an MSc in African Studies from the University of Oxford. © 2011 by Rafael Marques de Morais. All rights reserved. ii | Corruption in Angola Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................ ................................................................ ......................... 1 Introduction ................................ ................................................................ ................................ .... 2 I. Consolidation of Presidential Powers: Constitutional and Legal Measures ........................... 4 The Concept of Democracy ................................ ................................ ................................ ......... 4 The Consolidation Process ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 4 The Consequences ................................ ................................ ................................ ...................... 9 II. Tightening the Net: Available Space for Angolan Civil Society ............................... -

The Profitable and Untethered March to Global Resource Dominance!

Athens Journal of Business and Economics X Y GlencoreXstrata… The Profitable and Untethered March to Global Resource Dominance! By Nina Aversano Titos Ritsatos† Motivated by the economic causes and effects of their merger in 2013, we study the expansion strategy deployment of Glencore International plc. and Xstrata plc., before and after their merger. While both companies went through a series of international acquisitions during the last decade, their merger is strengthening effective vertical integration in critical resource and commodity markets, following Hymer’s theory of internationalization and Dunning’s theory of Eclectic Paradigm. Private existence of global dominant positioning in vital resource markets, posits economic sustainability and social fairness questions on an international scale. Glencore is alleged to have used unethical business tactics, increasing corruption, tax evasion and money laundering, while attracting the attention of human rights organizations. Since the announcement of their intended merger, the company’s market performance has been lower than its benchmark index. Glencore’s and Xstrata’s economic success came from operating effectively and efficiently in markets that scare off risk-averse companies. The new GlencoreXstrata is not the same company anymore. The Company’s new capital structure is characterized by controlling presence of institutional investors, creating adherence to corporate governance and increased monitoring and transparency. Furthermore, when multinational corporations like GlencoreXstrata increase in size attracting the attention of global regulation, they are forced by institutional monitoring to increase social consciousness. When ensuring full commitment to social consciousness acting with utmost concern with regard to their commitment by upholding rules and regulations of their home or host country, they have but to become “quasi-utilities” for the global industry. -

Workshop on Corruption and Human Rights in Third Countries

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES OF THE UNION DIRECTORATE B POLICY DEPARTMENT WORKSHOP CORRUPTION AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN THIRD COUNTRIES Abstract Defined as abuse of public trust for personal gain, corruption is present in all countries. The participants of this workshop discussed various ways that corruption is linked to human rights violations and examined specific challenges in individual countries such as South Africa, Angola and Russia. The recommendations for the EU included supporting civil society activists more effectively, developing international standards for the independence of anti-corruption bodies, establishing a UN Special Rapporteur, setting anti-corruption benchmarks for bilateral cooperation and monitoring the links of corrupt countries with EU Member States. EXPO/B/DROI/2013/03-04-07 March 2013 PE 433.728 EN Policy Department DG External Policies This workshop on 'Corruption and human rights in third countries' was requested by the European Parliament's Subcommittee on Human Rights. BASED ON PRESENTATIONS OF: Gareth SWEENEY, Transparency International ‘Linking acts of corruption with specific human rights’ Rafael MARQUES DE MORAIS, Journalist and Angolan anti-corruption campaigner 'Corruption in Africa and the Impact on Human Rights: Angola: A Case Study' Julia PETTENGILL, Research Fellow, Henry Jackson Society, London, Founder and Chair, Russia Studies Centre 'Impact of corruption on human rights in Russia' The exchange of views / hearing / public hearing can be followed online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/activities/committees/homeCom.do?language=EN&body=DROI -

GLENCORE: a Guide to the 'Biggest Company You've Never Heard

GLENCORE: a guide to the ‘biggest company you’ve never heard of’ WHO IS GLENCORE? Glencore is the world’s biggest commodities trading company and 16th largest company in the world according to Fortune 500. When it went public, it controlled 60% of the zinc market, 50% of the trade in copper, 45% of lead and a third of traded aluminium and thermal coal. On top of that, Glencore also trades oil, gas and basic foodstuffs like grain, rice and sugar. Sometimes refered to as ‘the biggest company you’ve never heard of’, Glencore’s reach is so vast that almost every person on the planet will come into contact with products traded by Glencore, via the minerals in cell phones, computers, cars, trains, planes and even the grains in meals or the sugar in drinks. It’s not just a trader: Glencore also produces and extracts these commodities. It owns significant mining interests, and in Democratic Republic of Congo it has two of the country’s biggest copper and cobalt operations, called KCC and MUMI. Glencore listed on the London Stock Exchange in 2011 in what is still the biggest ever Initial Public Offering (IPO) in the stock exchange’s history, with a valuation of £36bn. Glencore started life as Marc Rich & Co AG, set up by the eponymous and notorious commodities trader in 1974. In 1983 Rich was charged in the US with massive tax evasion and trading with Iran. He fled to Switzerland and lived in exile while on the FBI's most-wanted list for nearly two decades. -

Chapter 48 – Creative Destructor

Chapter 48 Creative destructor Starting in the late 19th century, when the Hall-Heroult electrolytic reduction process made it possible for aluminum to be produced as a commodity, aluminum companies began to consolidate and secure raw material sources. Alcoa led the way, acquiring and building hydroelectric facilities, bauxite mines, alumina refineries, aluminum smelters, fabricating plants and even advanced research laboratories to develop more efficient processing technologies and new products. The vertical integration model was similar to the organizing system used by petroleum companies, which explored and drilled for oil, built pipelines and ships to transport oil, owned refineries that turned oil into gasoline and other products, and even set up retail outlets around the world to sell their products. The global economy dramatically changed after World War II, as former colonies with raw materials needed by developed countries began to ask for a piece of the action. At the same time, more corporations with the financial and technical means to enter at least one phase of aluminum production began to compete in the marketplace. As the global Big 6 oligopoly became challenged on multiple fronts, a commodity broker with a Machiavellian philosophy and a natural instinct for deal- making smelled blood and started picking the system apart. Marc Rich began by taking advantage of the oil market, out-foxing the petroleum giants and making a killing during the energy crises of the 1970s. A long-time metals trader, Rich next eyed the weakened aluminum industry during the 1980s, when depressed demand and over-capacity collided with rising energy costs, according to Shawn Tully’s 1988 account in Fortune. -

Extractive Sectors and Illicit Financial Flows: What Role for Revenue Governance Initiatives?

U4 ISSUE November 2011 No 13 Extractive sectors and illicit financial flows: What role for revenue governance initiatives? Philippe Le Billon Anti- Corruption Resource Centre www.U4.no U4 is a web-based resource centre for development practitioners who wish to effectively address corruption challenges in their work. U4 is operated by the Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) – an independent centre for research on international development and policy – and is funded by AusAID (Australia), BTC (Belgium), CIDA (Canada), DFID (UK), GIZ (Germany), Norad (Norway), Sida (Sweden) and The Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. All views expressed in this Issue are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U4 Partner Agencies or CMI/ U4. (Copyright 2011 - CMI/U4) Extractive sectors and illicit financial flows: What role for revenue governance initiatives? By Philippe Le Billon Associate Professor, Department of Geography and Liu Institute for Global Issues, University of British Columbia U4 Issue October 2011 No 13 Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................................... iv Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................... v 1. Introduction -

Metal Men Metal Men Marc Rich and the $10 Billion Scam A

Metal Men Metal Men Marc Rich and the $10 Billion Scam A. Craig Copetas No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, scanning or any information storage retrieval system, without explicit permission in writing from the Author. © Copyright 1985 by A. Craig Copetas First e-reads publication 1999 www.e-reads.com ISBN 0-7592-3859-6 for B.D. Don Erickson & Margaret Sagan Acknowledgments [ e - reads] Acknowledgments o those individual traders around the world who allowed me to con- duct deals under their supervision so that I could better grasp the trader’s life, I thank you for trusting me to handle your business Tactivities with discretion. Many of those traders who helped me most have no desire to be thanked. They were usually the most helpful. So thank you anyway. You know who you are. Among those both inside and outside the international commodity trad- ing profession who did help, my sincere gratitude goes to Robert Karl Manoff, Lee Mason, James Horwitz, Grainne James, Constance Sayre, Gerry Joe Goldstein, Christine Goldstein, David Noonan, Susan Faiola, Gary Redmore, Ellen Hume, Terry O’Neil, Calliope, Alan Flacks, Hank Fisher, Ernie Torriero, Gordon “Mr. Rhodium” Davidson, Steve Bronis, Jan Bronis, Steve Shipman, Henry Rothschild, David Tendler, John Leese, Dan Baum, Bert Rubin, Ernie Byle, Steven English and the Cobalt Cartel, Michael Buchter, Peter Marshall, Herve Kelecom, Misha, Mark Heutlinger, Bonnie Cutler, John and Galina Mariani, Bennie (Bollag) and his Jets, Fredy Haemmerli, Wil Oosterhout, Christopher Dark, Eddie de Werk, Hubert Hutton, Fred Schwartz, Ira Sloan, Frank Wolstencroft, Congressman James Santini, John Culkin, Urs Aeby, Lynn Grebstad, Intertech Resources, the Kaypro Corporation, Harper’s magazine, Cambridge Metals, Redco v Acknowledgments [ e - reads] Resources, the Swire Group, ITR International, Philipp Brothers, the Heavy Metal Kids, and . -

A Crude Awakening

Dedicated to the inspiration of Jeffrey Reynolds ISBN 0 9527593 9 X Published by Global Witness Ltd P O Box 6042, London N19 5WP,UK Telephone:+ 44 (0)20 7272 6731 Fax: + 44 (0)20 7272 9425 e-mail: [email protected] a crude awakening The Role of the Oil and Banking Industries in Angola’s Civil War and the Plunder of State Assets http://www.oneworld.org/globalwitness/ 1 a crude awakening The Role of the Oil and Banking Industries in Angola’s Civil War and the Plunder of State Assets “Most observers, in and out of Angola, would agree that “There should be full transparency.The oil companies who corruption, and the perception of corruption, has been a work in Angola, like BP—Amoco, Elf,Total and Exxon and the critical impediment to economic development in Angola.The diamond traders like de Beers, should be open with the full extent of corruption is unknown, but the combination of international community and the international financial high military expenditures, economic mismanagement, and institutions so that it is clear these revenues are not syphoned corruption have ensured that spending on social services and A CRUDE AWAKENING A CRUDE development is far less than is required to pull the people of off but are invested in the country. I want the oil companies Angola out of widespread poverty... and the governments of Britain, the USA and France to co- operate together, not seek a competitive advantage: full Our best hope to ensure the efficient and transparent use of oil revenues is for the government to embrace a comprehensive transparency is in our joint interests because it will help to program of economic reform.We have and will continue to create a more peaceful, stable Angola and a more peaceful, encourage the Angolan Government to move in this stable Africa too.” direction....” SPEECH BY FCO MINISTER OF STATE, PETER HAIN,TO THE ACTION FOR SECRETARY OF STATE, MADELEINE ALBRIGHT, SUBCOMMITTEE ON FOREIGN SOUTHERN AFRICA (ACTSA) ANNUAL CONFERENCE, SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL OPERATIONS, SENATE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS, JUNE 16 1998. -

Petro-States -Predatory Or Developmental?

ECON-Report no. 62/2000, Projectno.30091 Public ISSN: 0803-5113, ISBN 82-7645 -407-0 HOB/LLu/Thdmbh, KjR, 4. October 2000 FNI-Report no. 11/2000 ISSN: 0801-2431, ISBN 82-7613 -398-3 HOB/LLdTHa/mbh, KjR, 4. October 2000 Petro-states - Predatory or Developmental? Final report from research project financed by Statoil and the Petropol Programme of the Research Council of Norway ECON Centre for EconomicAnalysis P.O. Box 6823 St. Olavs plass, 0130 Oslo, Norway. Phone: +4722 989850, Fax: +47 22110080 Fridtjof Nansen Institute P. O.Box 326, 1326 Lysaker, Norway. Phone: +47 67111900, Fax: +4767 111910 DISCLAIMER Portions of this document may be illegible in electronic image products. Images are produced from the best available original document. Petro-states - Predatory or Developmental? Table of Contents: EXEC~IVE S~M~Y .....................................................................................l 1 mTRoDucTIoN ..........................................................................................5 2 PERFORMANCE OF RESOURCE-RICH ECONOMIES ...........................7 3 sEMcHmG FoREHLmATIoN .........................................................l3 4 THE ROLE OF THE STATE IN DEVELOPMENT ...................................17 5 COUNTRY STUDIES .................................................................................25 5.1 kerbaijm ...........................................................................................25 5.2 hgola .................................................................................................32 -

Glencore: Notorious Crimes and Failures

Glencore: Notorious crimes and failures Mining giant Glencore has made aggressive use Presence: 50+ countries of complex corporate structure and tax havens Number of employees: 155.000 (2016)5 to deprive developing nations of tax revenues, while frequently being accused of human and Company activity environmental rights violations in the course of Main activities: production, sourcing, processing, refining, its business. transporting, storage, financing and supply of metals and minerals, energy products and agricultural products. Problem Analysis Country and location in which Swiss mining giant Glencore has made extensive efforts to exploit corporate power for its own advantage, often the violation occurred at the expense of human and environmental rights. It has As Glencore owns over 150 mining & metallurgical, oil made use of Investor–State dispute mechanisms when production and agricultural assets around the world, there governments have restricted its activity. It has adopted are many different countries involved and affected. a complex international structure to minimise its tax Ghana, Chad, Zambia, Bolivia, Colombia, Philippines, exposure and so deprived a number of developing nations Argentina etc.7 of tax revenues, including Zambia and Burkina Faso. It has been accused of causing human rights violations and Summary of the case environmental damage at mining operations as far afield as Response of Glencore to several of these issues http:// Peru and Australia. www.glencore.com/assets/public-positions/doc/ Company Glencores-response-to-the-2015-Public-Eye-Nomination. pdf & http://www.glencore.com/public-positions Main Company: Glencore plc. 1. ISDS cases Head office: Baar, Switzerland In 2016, Glencore initiated two ISDS (Investor State Registered office: Saint Helier, Jersey Dispute Settlement) cases. -

Angola's New President

Angola’s new president Reforming to survive Paula Cristina Roque President João Lourenço – who replaced José Eduardo dos Santos in 2017 – has been credited with significant progress in fighting corruption and opening up the political space in Angola. But this has been achieved against a backdrop of economic decline and deepening poverty. Lourenço’s first two years in office are also characterised by the politicisation of the security apparatus, which holds significant risks for the country. SOUTHERN AFRICA REPORT 38 | APRIL 2020 Key findings The anti-corruption drive is not transparent While fear was endemic among the people and President João Lourenço is accused of under Dos Santos, there is now ‘fear among targeting political opponents and protecting the elites’ due to the perceived politicised those who support him. anti-corruption drive. Despite this targeted approach, there is an Economic restructuring is leading to austerity attempt by the new president to reform the measures and social tension – the greatest risk economy and improve governance. to Lourenço’s government. After decades of political interference by The greatest challenge going forward is reducing the Dos Santos regime, the fight against poverty and reviving the economy. corruption would need a complete overhaul of Opposition parties and civil society credit the judiciary and public institutions. Lourenço with freeing up the political space The appointment of a new army chief led and media. to the deterioration and politicisation of the Angolan Armed Forces. Recommendations For the president and the Angolan government: Use surplus troops and military units to begin setting up cooperative farming arrangements Urgently define, fund and implement an action with diverse communities, helping establish plan to alleviate the effects of the recession on irrigation systems with manual labour. -

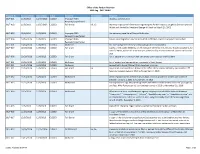

2017 and 2018 Source File from IQ

Office of the Pardon Attorney FOIA Log - 2017 DRAFT Request No. Received Date Closed Date Status Outcome Exemptions Request 2017-001 11/8/2016 11/25/2016 CLOSED Improper FOIA requests commutation Request/Unperfected 2017-002 11/8/2016 11/25/2016 CLOSED Full Denial b6, b5 Attorney request for information regarding the Pardon request sought by Bernard Donald Miskiv and denied by President George W. Bush on March 20, 2002 2017-003 10/4/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED Improper FOIA the clemency case file of Damon Burkhalter Request/Unperfected 2017-004 10/18/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED Improper FOIA advice on immigration issue as a result of ineffective counsel and police misconduct Request/Unperfected 2017-006 10/18/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED No Record the race and gender of these individuals granted commutation 2017-007 10/20/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED Full Grant copies of the public elements of the executive clemency file and any related documents for Danielle Metz, whose life sentence was commuted by President Barack Obama earlier this year 2017-008 10/28/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED Full Grant list of people who have had their sentences commuted by the President 2017-009 10/28/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED No Record list of pardon and commutation recipients in Excel format 2017-010 11/11/2016 12/8/2016 CLOSED No Record requesting to know if Robert Gallo received a pardon 2017-011 11/14/2016 12/9/2016 CLOSED Full Grant b6 any and all correspondence between the Office of the Pardon Attorney and Senator Jeff Sessions between January 2010 to November 14, 2016 2017-012 11/14/2016 12/9/2016 CLOSED No Record all correspondence to or from Rudy Giuliani or correspondence written on his behalf between January 1, 2001 to November 14, 2016 2017-013 11/21/2016 12/9/2016 CLOSED No Record correspondence logs documenting letters and other communication between your agency and Rep.