Chapter 48 – Creative Destructor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Profitable and Untethered March to Global Resource Dominance!

Athens Journal of Business and Economics X Y GlencoreXstrata… The Profitable and Untethered March to Global Resource Dominance! By Nina Aversano Titos Ritsatos† Motivated by the economic causes and effects of their merger in 2013, we study the expansion strategy deployment of Glencore International plc. and Xstrata plc., before and after their merger. While both companies went through a series of international acquisitions during the last decade, their merger is strengthening effective vertical integration in critical resource and commodity markets, following Hymer’s theory of internationalization and Dunning’s theory of Eclectic Paradigm. Private existence of global dominant positioning in vital resource markets, posits economic sustainability and social fairness questions on an international scale. Glencore is alleged to have used unethical business tactics, increasing corruption, tax evasion and money laundering, while attracting the attention of human rights organizations. Since the announcement of their intended merger, the company’s market performance has been lower than its benchmark index. Glencore’s and Xstrata’s economic success came from operating effectively and efficiently in markets that scare off risk-averse companies. The new GlencoreXstrata is not the same company anymore. The Company’s new capital structure is characterized by controlling presence of institutional investors, creating adherence to corporate governance and increased monitoring and transparency. Furthermore, when multinational corporations like GlencoreXstrata increase in size attracting the attention of global regulation, they are forced by institutional monitoring to increase social consciousness. When ensuring full commitment to social consciousness acting with utmost concern with regard to their commitment by upholding rules and regulations of their home or host country, they have but to become “quasi-utilities” for the global industry. -

Foreignpolicyleopold

Foreign Policy VOICE The 750 Million Dollar Man How a Swiss commodities giant used shell companies to make an Angolan general three-quarters of a billion dollars richer. BY Michael Weiss FEBRUARY 13, 2014 Revolutionary communist regimes have a strange habit of transforming themselves into corrupt crony capitalist ones and Angola -- with its massive oil reserves and budding crop of billionaires -- has proved no exception. In 2010, Trafigura, the world’s third-largest private oil and metals trader based in Switzerland, sold an 18.75-percent stake in one of its major energy subsidiaries to a high-ranking and influential Angolan general, Foreign Policy has discovered. The sale, which amounted to $213 million, appears on the 2012 audit of the annual financial statements of a Singapore-registered company, which is wholly owned by Gen. Leopoldino Fragoso do Nascimento. Details of the sale and purchaser are also buried within a prospectus document of the sold company which was uploaded to the Luxembourg Stock Exchange within the last week. “General Dino,” as he’s more commonly called in Angola, purchased the 18.75 percent stake not in any minor bauble, but in a $5 billion multinational oil company called Puma Energy International. By 2011, his shares were diluted to 15 percent; but that’s still quite a hefty prize: his stake in the company is today valued at around $750 million. The sale illuminates not only a growing and little-scrutinized relationship between Trafigura, which earned nearly $1 billion in profits in 2012, and the autocratic regime of 71-year-old Angolan President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who has been in power since 1979 -- but also the role that Western enterprise continues to play in the Third World. -

GLENCORE: a Guide to the 'Biggest Company You've Never Heard

GLENCORE: a guide to the ‘biggest company you’ve never heard of’ WHO IS GLENCORE? Glencore is the world’s biggest commodities trading company and 16th largest company in the world according to Fortune 500. When it went public, it controlled 60% of the zinc market, 50% of the trade in copper, 45% of lead and a third of traded aluminium and thermal coal. On top of that, Glencore also trades oil, gas and basic foodstuffs like grain, rice and sugar. Sometimes refered to as ‘the biggest company you’ve never heard of’, Glencore’s reach is so vast that almost every person on the planet will come into contact with products traded by Glencore, via the minerals in cell phones, computers, cars, trains, planes and even the grains in meals or the sugar in drinks. It’s not just a trader: Glencore also produces and extracts these commodities. It owns significant mining interests, and in Democratic Republic of Congo it has two of the country’s biggest copper and cobalt operations, called KCC and MUMI. Glencore listed on the London Stock Exchange in 2011 in what is still the biggest ever Initial Public Offering (IPO) in the stock exchange’s history, with a valuation of £36bn. Glencore started life as Marc Rich & Co AG, set up by the eponymous and notorious commodities trader in 1974. In 1983 Rich was charged in the US with massive tax evasion and trading with Iran. He fled to Switzerland and lived in exile while on the FBI's most-wanted list for nearly two decades. -

A List of the Records That Petitioners Seek Is Attached to the Petition, Filed Concurrently Herewith

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA IN RE PETITION OF STANLEY KUTLER, ) AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION, ) AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR LEGAL HISTORY, ) Miscellaneous Action No. ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN HISTORIANS, ) and SOCIETY OF AMERICAN ARCHIVISTS. ) ) MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR ORDER DIRECTING RELEASE OF TRANSCRIPT OF RICHARD M. NIXON’S GRAND JURY TESTIMONY OF JUNE 23-24, 1975, AND ASSOCIATED MATERIALS OF THE WATERGATE SPECIAL PROSECUTION FORCE Professor Stanley Kutler, the American Historical Association, the American Society for Legal History, the Organization of American Historians, and the Society of American Archivists petition this Court for an order directing the release of President Richard M. Nixon’s thirty-five-year- old grand jury testimony and associated materials of the Watergate Special Prosecution Force.1 On June 23-24, 1975, President Nixon testified before two members of a federal grand jury who had traveled from Washington, DC, to San Clemente, California. The testimony was then presented in Washington, DC, to the full grand jury that had been convened to investigate political espionage, illegal campaign contributions, and other wrongdoing falling under the umbrella term Watergate. Watergate was the defining event of Richard Nixon’s presidency. In the early 1970s, as the Vietnam War raged and the civil rights movement in the United States continued its momentum, the Watergate scandal ignited a crisis of confidence in government leadership and a constitutional crisis that tested the limits of executive power and the mettle of the democratic process. “Watergate” was 1A list of the records that petitioners seek is attached to the Petition, filed concurrently herewith. -

Copyright by Benjamin Jonah Koch 2011

Copyright by Benjamin Jonah Koch 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Benjamin Jonah Koch Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Watchmen in the Night: The House Judiciary Committee’s Impeachment Inquiry of Richard Nixon Committee: David Oshinsky, Supervisor H.W. Brands Dagmar Hamilton Mark Lawrence Michael Stoff Watchmen in the Night: The House Judiciary Committee’s Impeachment Inquiry of Richard Nixon by Benjamin Jonah Koch, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication To my grandparents For their love and support Acknowledgements I owe an immense debt of gratitude to my dissertation supervisor, David Oshinsky. When I arrived in graduate school, I did not know what it meant to be a historian and a writer. Working with him, especially in the development of this manuscript, I have come to understand my strengths and weaknesses, and he has made me a better historian. Thank you. The members of my dissertation committee have each aided me in different ways. Michael Stoff’s introductory historiography seminar helped me realize exactly what I had gotten myself into my first year of graduate school—and made it painless. I always enjoyed Mark Lawrence’s classes and his teaching style, and he was extraordinarily supportive during the writing of my master’s thesis, as well as my qualifying exams. I workshopped the first two chapters of my dissertation in Bill Brands’s writing seminar, where I learned precisely what to do and not to do. -

Nixon's Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968

Dark Quadrant: Organized Crime, Big Business, and the Corruption of American Democracy Online Appendix: Nixon’s Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968 By Jonathan Marshall “Though his working life has been passed chiefly on the far shores of the continent, close by the Pacific and the Atlantic, some emotion always brings Richard Nixon back to the Caribbean waters off Key Biscayne and Florida.”—T. H. White, The Making of the President, 19681 Richard Nixon, like millions of other Americans, enjoyed Florida and the nearby islands of Cuba and the Bahamas as refuges where he could leave behind his many cares and inhibitions. But he also returned again and again to the region as an important ongoing source of political and financial support. In the process, the lax ethics of its shadier operators left its mark on his career. This Sunbelt frontier had long attracted more than its share of sleazy businessmen, promoters, and politicians who shared a get-rich-quick spirit. In Florida, hustlers made quick fortunes selling worthless land to gullible northerners and fleecing vacationers at illegal but wide-open gambling joints. Sheriffs and governors protected bookmakers and casino operators in return for campaign contributions and bribes. In nearby island nations, as described in chapter 4, dictators forged alliances with US mobsters to create havens for offshore gambling and to wield political influence in Washington. Nixon’s Caribbean milieu had roots in the mobster-infested Florida of the 1940s. He was introduced to that circle through banker and real estate investor Bebe Rebozo, lawyer Richard Danner, and Rep. George Smathers. Later this chapter will explore some of the diverse connections of this group by following the activities of Danner during the 1968 presidential campaign, as they touched on Nixon’s financial and political ties to Howard Hughes, the South Florida crime organization of Santo Trafficante, and mobbed-up hotels and casinos in Las Vegas and Miami. -

Off the Record

About the Center for Public Integrity The CENTER FOR PUBLIC INTEGRITY, founded in 1989 by a group of concerned Americans, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, tax-exempt educational organization created so that important national issues can be investigated and analyzed over a period of months without the normal time or space limitations. Since its inception, the Center has investigated and disseminated a wide array of information in more than sixty Center reports. The Center's books and studies are resources for journalists, academics, and the general public, with databases, backup files, government documents, and other information available as well. The Center is funded by foundations, individuals, revenue from the sale of publications and editorial consulting with news organizations. The Joyce Foundation and the Town Creek Foundation provided financial support for this project. The Center gratefully acknowledges the support provided by: Carnegie Corporation of New York The Florence & John Schumann Foundation The John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation The New York Community Trust This report, and the views expressed herein, do not necessarily reflect the views of the individual members of the Center for Public Integrity's Board of Directors or Advisory Board. THE CENTER FOR PUBLIC INTEGRITY 910 17th Street, N.W. Seventh Floor Washington, D.C. 20006 Telephone: (202) 466-1300 Facsimile: (202)466-1101 E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2000 The Center for Public Integrity All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information and retrieval system, without permission in writing from The Center for Public Integrity. -

Metal Men Metal Men Marc Rich and the $10 Billion Scam A

Metal Men Metal Men Marc Rich and the $10 Billion Scam A. Craig Copetas No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, scanning or any information storage retrieval system, without explicit permission in writing from the Author. © Copyright 1985 by A. Craig Copetas First e-reads publication 1999 www.e-reads.com ISBN 0-7592-3859-6 for B.D. Don Erickson & Margaret Sagan Acknowledgments [ e - reads] Acknowledgments o those individual traders around the world who allowed me to con- duct deals under their supervision so that I could better grasp the trader’s life, I thank you for trusting me to handle your business Tactivities with discretion. Many of those traders who helped me most have no desire to be thanked. They were usually the most helpful. So thank you anyway. You know who you are. Among those both inside and outside the international commodity trad- ing profession who did help, my sincere gratitude goes to Robert Karl Manoff, Lee Mason, James Horwitz, Grainne James, Constance Sayre, Gerry Joe Goldstein, Christine Goldstein, David Noonan, Susan Faiola, Gary Redmore, Ellen Hume, Terry O’Neil, Calliope, Alan Flacks, Hank Fisher, Ernie Torriero, Gordon “Mr. Rhodium” Davidson, Steve Bronis, Jan Bronis, Steve Shipman, Henry Rothschild, David Tendler, John Leese, Dan Baum, Bert Rubin, Ernie Byle, Steven English and the Cobalt Cartel, Michael Buchter, Peter Marshall, Herve Kelecom, Misha, Mark Heutlinger, Bonnie Cutler, John and Galina Mariani, Bennie (Bollag) and his Jets, Fredy Haemmerli, Wil Oosterhout, Christopher Dark, Eddie de Werk, Hubert Hutton, Fred Schwartz, Ira Sloan, Frank Wolstencroft, Congressman James Santini, John Culkin, Urs Aeby, Lynn Grebstad, Intertech Resources, the Kaypro Corporation, Harper’s magazine, Cambridge Metals, Redco v Acknowledgments [ e - reads] Resources, the Swire Group, ITR International, Philipp Brothers, the Heavy Metal Kids, and . -

Glencore: Notorious Crimes and Failures

Glencore: Notorious crimes and failures Mining giant Glencore has made aggressive use Presence: 50+ countries of complex corporate structure and tax havens Number of employees: 155.000 (2016)5 to deprive developing nations of tax revenues, while frequently being accused of human and Company activity environmental rights violations in the course of Main activities: production, sourcing, processing, refining, its business. transporting, storage, financing and supply of metals and minerals, energy products and agricultural products. Problem Analysis Country and location in which Swiss mining giant Glencore has made extensive efforts to exploit corporate power for its own advantage, often the violation occurred at the expense of human and environmental rights. It has As Glencore owns over 150 mining & metallurgical, oil made use of Investor–State dispute mechanisms when production and agricultural assets around the world, there governments have restricted its activity. It has adopted are many different countries involved and affected. a complex international structure to minimise its tax Ghana, Chad, Zambia, Bolivia, Colombia, Philippines, exposure and so deprived a number of developing nations Argentina etc.7 of tax revenues, including Zambia and Burkina Faso. It has been accused of causing human rights violations and Summary of the case environmental damage at mining operations as far afield as Response of Glencore to several of these issues http:// Peru and Australia. www.glencore.com/assets/public-positions/doc/ Company Glencores-response-to-the-2015-Public-Eye-Nomination. pdf & http://www.glencore.com/public-positions Main Company: Glencore plc. 1. ISDS cases Head office: Baar, Switzerland In 2016, Glencore initiated two ISDS (Investor State Registered office: Saint Helier, Jersey Dispute Settlement) cases. -

The Anchor, Volume 97.11: November 14, 1984

Hope College Hope College Digital Commons The Anchor: 1984 The Anchor: 1980-1989 11-14-1984 The Anchor, Volume 97.11: November 14, 1984 Hope College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1984 Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Repository citation: Hope College, "The Anchor, Volume 97.11: November 14, 1984" (1984). The Anchor: 1984. Paper 23. https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1984/23 Published in: The Anchor, Volume 97, Issue 11, November 14, 1984. Copyright © 1984 Hope College, Holland, Michigan. This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Anchor: 1980-1989 at Hope College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Anchor: 1984 by an authorized administrator of Hope College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chinese Delegates Visit Hope Hope College had three ferent clubs which range from Chinese visitors on campus this photography to science. Each past Monday. May 20, Nanjing University's an- Nanjing University Vice- niversary, the clubs give special president Yuan Xiangwan, Pro- demonstrations of what they fessor of English Huang Cheng have done over the year. Feng, and International Educa- The three delegates are tion Professor Shang Zhen are visiting schools which they have halfway through a tour of various student exchanges with. They educational institutions in the were brought to Hope through a United States. grant from Exxon which has Mr. Yuan, with Mrs. Huang been providing for the interna- translating, addressed the facul- tionalizing of Hope's campus. ty at a luncheon. -

How Rupert Murdoch's Empire of Influence Remade The

HOW RUPERT MURDOCH’S EMPIRE OF INFLUENCE REMADE THE WORLD Part 1: Imperial Reach Murdoch And His Children Have Toppled Governments On Two Continents And Destabilized The Most Important Democracy On Earth. What Do They Want? By Jonathan Mahler And Jim Rutenberg 3rd April 2019 1. ‘I LOVE ALL OF MY CHILDREN’ Rupert Murdoch was lying on the floor of his cabin, unable to move. It was January 2018, and Murdoch and his fourth wife, Jerry Hall, were spending the holidays cruising the Caribbean on his elder son Lachlan’s yacht. Lachlan had personally overseen the design of the 140-foot sloop — named Sarissa after a long and especially dangerous spear used by the armies of ancient Macedonia — ensuring that it would be suitable for family vacations while also remaining competitive in superyacht regattas. The cockpit could be transformed into a swimming pool. The ceiling in the children’s cabin became an illuminated facsimile of the nighttime sky, with separate switches for the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. A detachable board for practicing rock climbing, a passion of Lachlan’s, could be set up on the deck. But it was not the easiest environment for an 86-year-old man to negotiate. Murdoch tripped on his way to the bathroom in the middle of the night. Murdoch had fallen a couple of other times in recent years, once on the stairs while exiting a stage, another time on a carpet in a San Francisco hotel. The family prevented word from getting out on both occasions, but the incidents were concerning. This one seemed far more serious. -

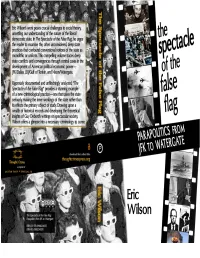

The Spectacle of the False-Flag

The Spectacle of the False-Flag THE SPECTACLE OF THE FALSE-FLAG: PARAPOLITICS FROM JFK TO WATERGATE Eric Wilson THE SPECTACLE OF THE FALSE-FLAG: PARAPOLITICS from JFK to WATERGATE Eric Wilson, Monash University 2015 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ This work is Open Access, which means that you are free to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to the author, that you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that you in no way, alter, transform, or build upon the work outside of its normal use in academic scholarship without express permission of the author and the publisher of this volume. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. First published in 2015 by Thought | Crimes an imprint of punctumbooks.com ISBN-13: 978-0988234055 ISBN-10: 098823405X and the full book is available for download via our Open Monograph Press website (a Public Knowledge Project) at: www.thoughtcrimespress.org a project of the Critical Criminology Working Group, publishers of the Open Access Journal: Radical Criminology: journal.radicalcriminology.org Contact: Jeff Shantz (Editor), Dept. of Criminology, KPU 12666 72 Ave. Surrey, BC V3W 2M8 [ + design & open format publishing: pj lilley ] I dedicate this book to my Mother, who watched over me as I slept through the spectacle in Dallas on November 22, 1963 and who was there to celebrate my birthday with me during the spectacle at the Watergate Hotel on June 17, 1972 Contents Editor©s Preface ................................................................