Querying Variants: Boccaccio's 'Commedia' and Data-Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Name Field Dates Project Title Abbondanza, Roberto History 1964

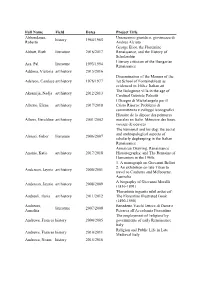

Full Name Field Dates Project Title Abbondanza, Umanesimo giuridico, giovinezza di history 1964/1965 Roberto Andrea Alciato George Eliot, the Florentine Abbott, Ruth literature 2016/2017 Renaissance, and the History of Scholarship Literary criticism of the Hungarian Acs, Pal literature 1993/1994 Renaissance Addona, Victoria art history 2015/2016 Dissemination of the Manner of the Adelson, Candace art history 1976/1977 1st School of Fontainebleau as evidenced in 16th-c Italian art The Bolognese villa in the age of Aksamija, Nadja art history 2012/2013 Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti I Disegni di Michelangelo per il Alberio, Elena art history 2017/2018 Cristo Risorto: Problemi di committenza e sviluppi iconografici Histoire de la dépose des peintures Albers, Geraldine art history 2001/2002 murales en Italie. Mémoire des lieux, voyage de oeuvres The humanist and his dog: the social and anthropological aspects of Almasi, Gabor literature 2006/2007 scholarly dogkeeping in the Italian Renaissance American Drawing, Renaissance Anania, Katie art history 2017/2018 Historiography, and The Remains of Humanism in the 1960s 1. A monograph on Giovanni Bellini 2. An exhibition on late Titian to Anderson, Jaynie art history 2000/2001 travel to Canberra and Melbourne, Australia A biography of Giovanni Morelli Anderson, Jaynie art history 2008/2009 (1816-1891) 'Florentinis ingeniis nihil ardui est': Andreoli, Ilaria art history 2011/2012 The Florentine Illustrated Book (1490-1550) Andreoni, Benedetto Varchi lettore di Dante e literature 2007/2008 Annalisa Petrarca all'Accademia Fiorentina The employment of 'religiosi' by Andrews, Frances history 2004/2005 governments of early Renaissance Italy Religion and Public Life in Late Andrews, Frances history 2010/2011 Medieval Italy Andrews, Noam history 2015/2016 Full Name Field Dates Project Title Genoese Galata. -

Lawyers in the Florence Consular District

Lawyers in the Florence Consular District (The Florence district contains the regions of Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany) Emilia-Romagna Region Disclaimer: The U.S. Consulate General in Florence assumes no responsibility or liability for the professional ability, reputation or the quality of services provided by the persons or firms listed. Inclusion on this list is in no way an endorsement by the Department of State or the U.S. Consulate General. Names are listed alphabetically within each region and the order in which they appear has no other significance. The information on the list regarding professional credentials, areas of expertise and language ability is provided directly by the lawyers. The U.S. Consulate General is not in a position to vouch for such information. You may receive additional information about the individuals by contacting the local bar association or the local licensing authorities. City of Bologna Attorneys Alessandro ALBICINI - Via Marconi 3, 40122 Bologna. Tel: 051/228222-227552. Fax: 051/273323. E- mail: [email protected]. Born 1960. Degree in Jurisprudence. Practice: Commercial law, Industrial, Corportate. Languages: English and French. U.S. correspondents: Kelley Drye & Warren, 101 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10178, Gordon Altman Butowski, 114 West 47th Street, New York, NY 10036- 1510. Luigi BELVEDERI – Via degli Agresti 2, 40123 Bologna. Tel: 051/272600. Fax: 051/271506. E-mail: [email protected]. Born in 1950. Degree in Jurisprudence. Practice: Freelance international attorney since 1978. Languages: English and Italian. Also has office in Milan Via Bigli 2, 20121 Milan Cell: 02780031 Fax: 02780065 Antonio CAPPUCCIO – Piazza Tribunali 6, 40124 Bologna. -

(G.N. Faenza, Battaglione Unico, 2ª Compagnia, Elenco Dei Cittadini Inscritti Al Controllo Del Servizio Ordinario

(G.N. Faenza, Battaglione Unico, 2ª Compagnia, Elenco dei Cittadini inscritti al Controllo del servizio ordinario. 1863?). C CADET ARISTIDE Nato a Roma il 2.10.1841, morto a Faenza il 12.08.1868, direttore dell'Orfanotrofio Maschi lascia In morte del professor Girolamo Tassinari , 1865. (A. Zecchini, Preti e cospiratori nella terra del Duce ). CADUTI Vicenza: Grossi Antonio, Lama Angelo, Liverani Giuseppe, Merendi Andrea, Querzola Achille, Servadei Giovanni, Toschi Pietro, Violani Orazio. Roma 1849: Ancarani Andrea, Ghigi Clemente, Della Vedova Marta, Fenati Cesare, Galvani Paolo, Liverani Antonio, Massari Marco (Sante), Minghetti Agostino, Padovani Francesco, Pezzi Antonio, Savini Francesco. San Martino: Castaldi Federico, Castellani Orlando, Melandri Sante, Merendi Settimio, Sangiorgi Angelo. 1860: Morini Luigi, Toni Marco, Montanari Domenico, a Borgoforte Castelfidardo: Sangiorgi Francesco. Milazzo: Samorini Dionisio. Mola di Gaeta: Gaddoni Francesco, morto 18.01.1861 di febbre tifoidea, Bezzecca: Argnani Achille, Gheba Giuseppe, Marchetti Ferdinando, Monti Ulisse.1859, “Dei Giovani Valorosi del Comune di Faenza che nell’ultima guerra combattendo rimasero mutilati od invalidi, e delle Famiglie.” Merendi Settimio, volontario 6° Rgt. Aosta, 1° btg., 2ª Comp., morto a Solferino. Castaldi Federico, 2° Rgt. Brigata Aosta, morto il 26.06.59 in seguito alle gravi ferite riportate a Solferino. Melandri Sante, milite volontario, 11° Rgt. Fanteria, 12ª Comp., morto a Solferino. (A.S.F.). 1868, 4 marzo: “Elenco de’ Giovani Faentini caduti nella campagna del 1866” : Montanari Domenico di Giuseppe, condizione famiglia miserabile, luogotenente RR.CC., Gheba Giuseppe, fu Lorenzo, condizione famiglia miserabile, Corpo dei Volontari, Argnani Achille, fu Antonio, condizione famiglia miserabile, Corpo dei Volontari, Campi Salvatore, fu Natale, condizione famiglia miserabile, Corpo dei Volontari, Drei Giacomo, di Antonio, condizione famiglia miserabile, Corpo dei Volontari. -

The Original Documents Are Located in Box 16, Folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 16, folder “6/3/75 - Rome” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 16 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library 792 F TO C TATE WA HOC 1233 1 °"'I:::: N ,, I 0 II N ' I . ... ROME 7 480 PA S Ml TE HOUSE l'O, MS • · !? ENFELD E. • lt6~2: AO • E ~4SSIFY 11111~ TA, : ~ IP CFO D, GERALD R~) SJ 1 C I P E 10 NTIA~ VISIT REF& BRU SE 4532 UI INAl.E PAL.ACE U I A PA' ACE, TME FFtCIA~ RESIDENCE OF THE PR!S%D~NT !TA y, T ND 0 1 TH HIGHEST OF THE SEVEN HtL.~S OF ~OME, A CTENT OMA TtM , TH TEMPLES OF QUIRl US AND TME s E E ~oc T 0 ON THIS SITE. I THE CE TER OF THE PR!SENT QU?RINA~ IAZZA OR QUARE A~E ROMAN STATUES OF C~STOR .... -

Agrintesa Societa' Agricola Cooperativa Domanda Carpetta N. 1708586 Settore: Ortofrutticolo

FILIERA 45 - AGRINTESA SOCIETA' AGRICOLA COOPERATIVA DOMANDA CARPETTA N. 1708586 SETTORE: ORTOFRUTTICOLO importo Sede contributo Codice progetto Domanda Ragione Sociale Provincia CUAA progetto NOTE Investimento ammesso PROG ammesso 1 F45-111-114/1-RA 1778212 VERNOCCHI DAVIDE Ravenna RA VRNDVD64T30D704Z 675,00 540,00 2 F45-111-114/2-RA 1778215 BALLARDINI PIERLUIGI Bagnacavallo RA BLLPLG51M24A547N 675,00 540,00 3 F45-111-114/3-MO 1778443 SOLMI GIOVANNI Spilamberto MO SLMGNN64P12F257K 675,00 540,00 4 F45-111-114/4-BO 1778446 GOLINI PAOLO Mordano BO GLNPLA53S24F718Q 675,00 540,00 5 F45-111-114/5-RA 1778478 DREI RAFFAELE Faenza RA DRERFL65P10D458F 675,00 540,00 6 F45-111-114/6-RA 1778483 ALBERGHI STEFANO Castel Bolognese RA LBRSFN70A07C065K 675,00 540,00 4.050,00 3.240,00 1 F45-121/06-BO 1652123 Musiani Roberto Anzola dell'Emilia BO MSNRRT72C30C107R 107.200,00 37.520,00 2 F45-121/07-RA 1654235 Società agricola Santa Maria di Castellari s.s. Faenza RA 01412310391 112.350,00 39.322,50 3 F45-121/08-RA 1657625 Bucci Giordano Solarolo RA BCCGDN65E12D458A 75.818,00 26.536,30 Az. Agr. Bedeschi Pietro, Gianpaolo, Sant'Agata sul 4 F45-121/09-RA 1657801 Tagliaferri Marina e Bandini Maria Rosa Santerno RA 00459080396 94.200,00 32.970,00 5 F45-121/100-RA 1665684 Budellazzi Luigi Faenza RA BDLLGU60L16D458U 42.070,00 14.724,50 6 F45-121/101-MO 1665756 Solmi Giovanni Spilamberto MO SLMGNN64P12F257K 53.300,00 18.665,00 7 F45-121/102-RA 1665757 Ranzi Stefano e Giuseppe Faenza RA 01192440392 45.265,10 15.842,79 8 F45-121/103-MO 1665768 Amidei Maria Rosa Vignola MO MDAMRS62C66F257F 107.050,00 37.467,50 Castelfranco 9 F45-121/104-MO 1665772 Balsemin Monica Emilia Mo BLSMNC74E43C107N 26.800,00 9.380,00 Gaudenzi Ennio e Ravaioli Irene s.s. -

The Plague of 1630 in Modena (Italy) Through the Study of Parish Registers

Medicina Historica 2019; Vol. 3, N. 3: 139-148 © Mattioli 1885 Original article: history of medicine The plague of 1630 in Modena (Italy) through the study of parish registers Mirko Traversari1, Diletta Biagini1, Giancarlo Cerasoli2, Raffaele Gaeta3, Donata Luiselli1, Giorgio Gruppioni1, Elisabetta Cilli1 1Department of Cultural Heritage, University of Bologna, Ravenna, Italy; 2 Gruppo AUSL Romagna Cultura, Italy; 3 Division of Paleopathology, Department of Translational Research and New Technologies in Medicine and Surgery, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy Abstract. The purpose of this paper is to study the impact this disease had on the community in Modena during the epidemic in 1630 and highlight the real course of the disease that brought Modena and whole Europe to its knees in the 17th century. The investigation was carried out by transcribing and studying the par- ish certificates of death for the period 1625-1635. This study confirmed that the plague epidemic in Modena began as early as 1629, and then exploded in the most virulent form since the beginning of summer 1630 and reached its peak in August of the same year, when it caused about seven hundred victims. Key words: plague, infectious diseases, paleopathology Introduction today, newspapers and articles discuss about the plague as an active disease among rodents and, occasionally, Infectious diseases have accompanied humans among human beings. Many historians, doctors, epi- since ancient times and have marked their history, demiologists and writers have ventured into the study sometimes in a catastrophic way. In particular, every- of this disease, in telling its story and the impact of one has heard of or read something about the plague. -

Early Sources Informing Leon Battista Alberti's De Pictura

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Alberti Before Florence: Early Sources Informing Leon Battista Alberti’s De Pictura A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Peter Francis Weller 2014 © Copyright by Peter Francis Weller 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Alberti Before Florence: Early Sources Informing Leon Battista Alberti’s De Pictura By Peter Francis Weller Doctor of Philosophy in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Charlene Villaseñor Black, Chair De pictura by Leon Battista Alberti (1404?-1472) is the earliest surviving treatise on visual art written in humanist Latin by an ostensible practitioner of painting. The book represents a definitive moment of cohesion between the two most conspicuous cultural developments of the early Renaissance, namely, humanism and the visual arts. This dissertation reconstructs the intellectual and visual environments in which Alberti moved before he entered Florence in the curia of Pope Eugenius IV in 1434, one year before the recorded date of completion of De pictura. For the two decades prior to his arrival in Florence, from 1414 to 1434, Alberti resided in Padua, Bologna, and Rome. Examination of specific textual and visual material in those cities – sources germane to Alberti’s humanist and visual development, and thus to the ideas put forth in De pictura – has been insubstantial. This dissertation will therefore present an investigation into the sources available to Alberti in Padua, Bologna and Rome, and will argue that this material helped to shape the prescriptions in Alberti’s canonical Renaissance tract. By more fully accounting for his intellectual and artistic progression before his arrival in Florence, this forensic reconstruction aims to fill a gap in our knowledge of Alberti’s formative years and thereby underline impact of his early career upon his development as an art theorist. -

Ravenna, a Study by Edward Hutton</H1>

Ravenna, A Study by Edward Hutton Ravenna, A Study by Edward Hutton Produced by Ted Garvin, Leonard Johnson and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. RAVENNA A STUDY BY EDWARD HUTTON ILLUSTRATED IN COLOUR AND LINE by HARALD SUND 1913 TO MY FRIEND ARTHUR SYMONS IN AFFECTIONATE HOMAGE page 1 / 345 PREFACE My intention in writing this book has been to demonstrate the unique importance of Ravenna in the history of Italy and of Europe, especially during the Dark Age from the time of Alaric's first descent into the Cisalpine plain to the coming of Charlemagne. That importance, as it seems to me, has been wholly or almost wholly misunderstood, and certainly, as I understand it, has never been explained. In this book, which is offered to the public not without a keen sense of its inadequacy, I have tried to show in as clear a manner as was at my command, what Ravenna really was in the political geography of the empire, and to explain the part that position allowed her to play in the great tragedy of the decline and fall of the Roman administration. If I have succeeded in this I am amply repaid for all the labour the book has cost me. The principal sources, both ancient and modern, which I have consulted in the preparation of this volume have been cited, but I must here acknowledge the special debt I owe to the late Dr. Hodgkin, to Professor Diehl, to Dr. Corrado Ricci, and to the many contributors to the various Italian Bollettini which I have ransacked. -

The Decameron, Vol. II. by Giovanni Boccaccio</H1>

The Decameron, Vol. II. by Giovanni Boccaccio The Decameron, Vol. II. by Giovanni Boccaccio Produced by Donna Holsten THE DECAMERON OF GIOVANNI BOCCACCIO Faithfully Translated By J.M. Rigg with illustrations by Louis Chalon VOLUME II page 1 / 510 CONTENTS - FIFTH DAY - NOVEL I. - Cimon, by loving, waxes wise, wins his wife Iphigenia by capture on the high seas, and is imprisoned at Rhodes. He is delivered by Lysimachus; and the twain capture Cassandra and recapture Iphigenia in the hour of their marriage. They flee with their ladies to Crete, and having there married them, are brought back to their homes. NOVEL II. - Gostanza loves Martuccio Gomito, and hearing that he is dead, gives way to despair, and hies her alone aboard a boat, which is wafted by the wind to Susa. She finds him alive in Tunis, and makes herself known to him, who, having by his counsel gained high place in the king's favour, marries her, and returns with her wealthy to Lipari. NOVEL III. - Pietro Boccamazza runs away with Agnolella, and encounters a gang of robbers: the girl takes refuge in a wood, and is guided to a castle. Pietro is taken, but escapes out of the hands of the robbers, and after some adventures arrives at the castle where Agnolella is, marries her, and returns with her to Rome. NOVEL IV. - Ricciardo Manardi is found by Messer Lizio da Valbona with his daughter, whom he marries, and remains at peace with her father. page 2 / 510 NOVEL V. - Guidotto da Cremona dies leaving a girl to Giacomino da Pavia. -

Reading the Decameron from Boccaccio to Salviati A

READING THE DECAMERON FROM BOCCACCIO TO SALVIATI A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Daniel Thomas Tonozzi February 2010 © 2010 Daniel Thomas Tonozzi READING THE DECAMERON FROM BOCCACCIO TO SALVIATI Daniel Thomas Tonozzi, Ph.D. Cornell University 2010 My dissertation analyzes the assumptions and anxieties the Decameron, in complete and expurgated forms, reveals about the practice of reading, the category of reader, and the materiality of the text. I also consider stories from the Decameron as a dialogue among the narrators who discuss the responsibilities of readers and writers. My introduction sets up how I engage existing concepts of hermeneutics, reader-response theory, and imitation. In Chapter 1, I discuss the practice of reading in terms of humanist imitation. I privilege an appreciation and examination of method, highlighting two responsibilities that weigh on the Decameron’s readers: to recognize useful textual models and to execute those models in a way that balances their replication with innovation. In Chapter 2, I consider the Decameron’s assumptions about how readers judge useful models and discern opportunities for pleasure. I propose a reader who simultaneously acts as an individual agent and a member of a larger community. I identify two divergent models for communal participation that are marked by gender. In Chapter 3, I analyze the interventions of expurgators Vincenzo Borghini and Lionardo Salviati, illustrating how their editions manipulate the tensions inherent in any censored book between its status as literature and its mandate to represent and support a specific ideology. -

Two Fifteenth-Century Florentine Uomini Famosi Cycles

RECALLING THE COUNCIL OF FERRARA AND FLORENCE: TWO FIFTEENTH-CENTURY FLORENTINE UOMINI FAMOSI CYCLES by CARRIE CHISM LIEN TANJA JONES, COMMITTEE CHAIR MINDY NANCARROW NOA TUREL A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art and Art History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2015 Copyright Carrie Chism Lien 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT In this thesis, I examine the two extant Florentine fresco cycles of famous men, or uomini famosi created in the quattrocento: Andrea del Castagno’s Famous Men and Women (1448-51) [figure 1], created for the private residence of the Carducci family, and Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Apotheosis of St. Zenobius and Famous Men (1482-83) [figure 2] located in the Sala dei Gigli in the Palazzo Vecchio, suggesting that each recalled the Council of Ferrara and Florence (1438- 39), called by Pope Eugenius VI in 1438 in an attempt to unify the Eastern and Western divisions of the Church. While extensive art historical study has been dedicated to each cycle individually, neither installation has been considered in relation to contemporary political events or in relation to the other. Reference to the Council, its temporary success, and the lasting effect that it had in the hearts of Florentines, I suggest, aids in understanding what have been, in the past, identified as the cycles’ “unusual” iconography, such as the inclusion of contemporary Florentine men and a somewhat minor saint placed as a central figure. To support this expanded analysis of the frescoes, I first consider the history of uomini famosi cycles, demonstrating that, indeed, both Florentine cycles contain unprecedented groupings and portrayals, intentional departures from cycles produced outside of Florence. -

The Decameron of Giovanni Boccaccio, by 1

The Decameron of Giovanni Boccaccio, by 1 The Decameron of Giovanni Boccaccio, by Giovanni Boccaccio This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Decameron of Giovanni Boccaccio Author: Giovanni Boccaccio Translator: John Payne Release Date: December 3, 2007 [EBook #23700] Language: English The Decameron of Giovanni Boccaccio, by 2 Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DECAMERON *** Produced by Ted Garvin, Linda Cantoni, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net [Transcriber's Note: The original text does not observe the normal convention of placing quotation marks at the beginnings of paragraphs within a multiple-paragraph quotation. This idiosyncrasy has been preserved in this e-text. Archaic spellings have been preserved, but obvious printer errors have been corrected. In the untranslated Italian passage in Day 3, Story 10, the original is missing the accents, which have been added using an Italian edition of Decameron (Milan: Mursia, 1977) as a guide. John Payne's translation of The Decameron was originally published in a private printing for The Villon Society, London, 1886. The American edition from which this e-text was prepared is undated.] The Decameron of Giovanni Boccaccio Translated by John Payne [Illustration] WALTER J. BLACK, INC. 171 Madison Avenue NEW YORK, N.Y. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Contents PROEM.