Faith Working Through Love 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Liele :Negro Slavery's Prophet of Deliverance

George Liele :Negro Slavery's Prophet of Deliverance EORGE LIELE (Lisle, Sharpe) is o:p.e of the unsung heroes of Greligious history, whose exploits and attainments have gone vir tually unnoticed except in a few little-known books and journals of Negro history. Liele's spectacular but steady devotion to the cause of his Master began with his conversion in 1773 and subsequent exercise of his ·cc call" in his own and nearby churches; it ended with mUltiple thousands of simple black folk raisec;I from the callous indignity of human bondage to freedom and a glorious citizenship in the king dom of God, largely as a consequence of this man's Christian witness in life and word. George was born a slave to slave parents, Liele and Nancy, in servitude to the family of Henry Sharpe in Virginia. From his birth, about 1750, to his eventual freedom in 1773, Liele belonged to the Sharpe family, with whom' he was removed to Burke County, Georgia, prior to 1770. Henry Sharpe, his master, was a Loyalist supporter and a deacon in the Buckhead Creek Baptist Church pastored by the Rev. Matthew Moore. Of his own parents and early years Liele reported in a letter of 1791 written from. Kingston, Jamaica: ~'I was born in Virginia, my father's name was Liele, and my mother's name Nancy; I cannot ascertain much of them, as I went to several parts of America when young, and at length resided in New Georgia; but was informed both by white and black people, that my father was the only black person who knew the Lord in a spiritual way in that country. -

Roots and Routes

1 ROOTS AND ROUTES The journey embarked upon by Black Loyalists destined for the Baha- mas was not marked by a rupture from their past experiences in colonial America, but rather reflected a continuity shaped by conditions of en- slavement and their entry into a British colony as persons of color. Like West African victims of the transatlantic slave trade, Black Loyalists arriv- ing in the Bahamas did not come as a tabula rasa, but rather brought with them various ideas aboutproof religion, land, politics, and even freedom. Thus, upon arrival in the Bahamas the lessons of the Revolutionary War were appropriated and reinterpreted by Black Loyalist men and women in a va- riety of ways, often with varying consequences. Such complex transmuta- tions within the Bahamas invite an analytical approach that examines the roots of such thought as it emerged out of the social and political world of colonial British North America. A brief examination of leading Black Loyalists in the Bahamas demon- strates that the world they lived in was indelibly shaped by the world they left behind. Prince Williams’ remarkable story began in colonial Georgia where he was born free, but was later “cheated out of his freedom and sold to an American.”1 Although his slave owner is never mentioned by name, Williams’ account reveals that he was forced to serve “this man” when “the British troops came to Georgia.” Taking advantage of the chaos of the American Revolution, Williams, in an act of self-assertion, escaped to the British side in order to claim freedom as a Black Loyalist. -

Dynamics in the Process of Contextualization Facilitated by A

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Müri, Sabine (2016) Dynamics in the process of contextualization facilitated by a West-European researcher: contextualizing the OT notion of ‘sin’ in the cultural context of the Kongo people in Brazzaville. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/21638/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Sweden 2020 International Religious Freedom Report

SWEDEN 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution protects “the freedom to practice one’s religion alone or in the company of others” and prohibits discrimination based on religion. In March, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) declined to hear the case of two midwives who said the regional hospitals, and by extension the state, had infringed on their religious beliefs and freedom of choice by denying them employment due to their opposition to abortion, which is legal in the country. In September, the Malmo Administrative Court overturned the Bromolla Municipality’s ban on prayer during working hours. In November, the Malmo Administrative Court overturned the ban on hijabs, burqas, niqabs, and other face- and hair-covering garments for students and employees in preschools and elementary schools introduced by Skurup and Staffanstorp Municipalities. In January, a government inquiry proposed a ban on the establishment of new independent religious schools, beginning in 2023, and increased oversight on existing schools having a religious orientation. The Migration Agency’s annual report, released in February, reported large regional variations in the assessment of asylum cases of Christian converts from the Middle East and elsewhere. Some politicians from the Sweden Democrats, the country’s third largest political party, made denigrating comments about Jews and Muslims. Prime Minister Stefan Lofven and other politicians condemned anti-Semitism and religious intolerance. The Prime Minister announced his country’s endorsement of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of anti-Semitism, including its list of examples of anti- Semitism. The government continued funding programs aimed at combating racism and anti-Semitism and reducing hate crimes, including those motivated by religion. -

The Development of Baptist Thought in the Jamaican Context

THE DEVELOPMENT OF BAPTIST THOUGHT IN THE JAMAICAN CONTEXT A Case Study by MICHAEL OLIVER FISHER Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Theology) Acadia University Spring Convocation 2010 © by MICHAEL OLIVER FISHER, 2010. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………...................................…………… vi LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS…………………………………………………………….………………..…. vii ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………………….…...… viii INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………....……………..... 1 CHAPTERS: 1. BAPTIST LIFE AND THOUGHT AS CONTEXT…………………………………………... 5 1.1 The Polygenetic Nature of Baptist Origins……………….…………… 7 1.2 A Genetic History of Baptist Thought…………………………………… 13 1.3 General Patterns in Baptist Thought…………………………….…….... 25 1.4 Relevant Themes in Baptist Life and Thought……......………...…... 34 2. THE HISTORY OF BAPTISTS IN JAMAICA………………….…………………………....... 41 2.1 A Chronological History of Jamaica………………..…………..………… 42 2.2 An Introduction to the Baptist Mission……....……………….………… 51 2.2.1 American Influences…………………..…………………………….. 53 2.2.2 British Influences……………………...……………………………… 59 2.3 The Development of the Baptist Mission in Jamaica...………….…. 72 3. FOUNDATIONS OF AFRO‐CHRISTIAN THOUGHT IN JAMAICA……………….… 91 3.1 Bases of Jamaican Religious Thought………………………...………..... 93 3.1.1 African Religious Traditions……………………………...….…… 94 3.1.2 Missiological Religious Thought…………………………….…... 101 3.2 The Great Revival and the Rise of Afro‐Christian Theology......... 118 3.3 Features of Jamaica Religious -

The Religious Landscape of Sweden

The Religious Landscape of Sweden Sweden of Landscape Religious The Erika Willander The Religious Landscape of Sweden – Affinity, Affiliation and Diversity in the 21st Century The Religious What does religious practice and faith look like in today’s Swedish society? Century 21st the in Diversity and Affiliation Affinity, – Landscape of Sweden This report draws the contour lines of religious diversity in Sweden, focusing – Affinity, Affiliation and Diversity on the main religious affiliations and how these groups differ in terms of in the 21st Century gender, age, education and income. The report also discuss relations between religion and social cohesion i Sweden. The Religious Landscape of Sweden – Affinity, Affiliation and Diversity during the 21st Century is a report authored by Erika Willander, PhD, Researcher in Sociology at Uppsala University. Erika Willander Erika Box 14038 • 167 14 Bromma • www.sst.a.se ISBN: 978-91-983453-4-6 A report from Swedish Agency for Support to Faith Communities Erika Willander The Religious Landscape of Sweden – Affinity, Affiliation and Diversity in the 21st Century Swedish Agency for Support to Faith Communities Stockholm 2019 1 Erika Willander The Religious Landscape of Sweden – Affinity, Affiliation and Diversity in the 21st Century This report was first published in the spring of 2019 under the titleSveriges religiösa landskap - samhörighet, tilhörighet och mångfald under 2000-talet. Swedish Agency for Support to Faith Communities (SST) Box 14038, 167 14 Bromma Phone : +46 (0) 8-453 68 70 [email protected], www.myndighetensst.se Editor: Max Stockman Translation: Martin Engström Design: Helena Wikström, HewiDesign – www.hewistuff.se Print: DanagårdLiTHO, 2019 ISBN: 978-91-983453-4-6 2 3 Table of Contents About The Swedish Agency for Faith Communities . -

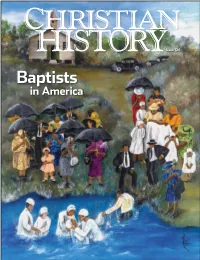

Baptists in America LIVE Streaming Many Baptists Have Preferred to Be Baptized in “Living Waters” Flowing in a River Or Stream On/ El S

CHRISTIAN HISTORY Issue 126 Baptists in America Did you know? you Did AND CLI FOUNDING SCHOOLS,JOININGTHEAR Baptists “churchingthe MB “se-Baptist” (self-Baptist). “There is good warrant for (self-Baptist). “se-Baptist” manyfession Their shortened but of that Faith,” to described his group as “Christians Baptized on Pro so baptized he himself Smyth and his in followers 1609. dam convinced him baptism, the of need believer’s for established Anglican Mennonites Church). in Amster wanted(“Separatists” be to independent England’s of can became priest, aSeparatist in pastor Holland BaptistEarly founder John Smyth, originally an Angli SELF-SERVE BAPTISM ING TREES M selves,” M Y, - - - followers eventuallyfollowers did join the Mennonite Church. him as aMennonite. They refused, though his some of issue and asked the local Mennonite church baptize to rethought later He baptism the themselves.” put upon two men singly“For are church; no two so may men a manchurching himself,” Smyth wrote his about act. would later later would cated because his of Baptist beliefs. Ironically Brown Dunster had been fired and in his 1654 house confis In fact HarvardLeague Henry president College today. nial schools,which mostof are members the of Ivy Baptists often were barred from attending other colo Baptist oldest college1764—the in the United States. helped graduates found to Its Brown University in still it exists Bristol, England,founded at in today. 1679; The first Baptist college, Bristol Baptist was College, IVY-COVERED WALLSOFSEPARATION LIVE “E discharged -

George Liele Bib

Bibliography Related to George Liele Liele, George. “An Account of Several Baptist Churches, Consisting Chiefly of Negro Slaves: Particularly of One at Kingston, in Jamaica; and Another at Savannah in Georgia (1793).” In Unchained Voices: An Anthology of Black Authors in the English-speaking World of the Eighteenth Century. Edited by Vincent Carretta. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004. _____. “The Covenant of the Anabaptist Church: Began in America 1777, in Jamaica, Dec. 1783.” 1796. British Baptist material, Angus Library of Regents Park College, Oxford, England, reel 1, no. 14.; Publication (Historical Commission, Southern Baptist Convention), MF # 4265. Liele, George and Andrew Bryan. “Letters from Pioneer Black Baptists.” In Afro-American Religious History: A Documentary Witness. Edited by Milton C. Sernett. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1985. “Letters Showing the Rise and Progress of the Early Negro Churches of Georgia and the West Indies.” Comprised of “An Account of Several Baptist Churches, Consisting Chiefly of Negro Slaves: Particularly of One at Kingston, in Jamaica; and Another at Savannah in Georgia,” and “Sketches of the Black Baptist Church at Savannah, in Georgia: And of Their Minister Andrew Bryan, Extracted from Several Letters.” Journal of Negro History 1 no. 1 (Jan. 1916): 69-92. Ballew, Christopher Brent and Moses Baker. The Impact of African-American Antecedents on the Baptist Foreign Missionary Movement, 1782-1825. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2004. Brooks, Walter H. A History of Negro Baptist Churches in America. Washington, D.C.: Press of R.L. Pendelton, 1910. Copyright, University Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2004. -

CEC Member Churches

Conference of European Churches MEMBER CHURCHES CEC Member Churches This publication is the result of an initiative of the Armenian Apostolic Church, produced for the benefit of CEC Member Churches, in collaboration with the CEC secretariat. CEC expresses its gratitude for all the work and contributions that have made this publication possible. Composed by: Archbishop Dr. Yeznik Petrosyan Hasmik Muradyan Dr. Marianna Apresyan Editors: Dr. Leslie Nathaniel Fr. Shahe Ananyan Original design concept: Yulyana Abrahamyan Design and artwork: Maxine Allison, Tick Tock Design Cover Photo: Albin Hillert/CEC 1 2 CEC MEMBER CHURCHES - EDITORIAL TEAM Archbishop Yeznik Petrosyan, Dr. of Theology (Athens University), is the General Secretary of the Bible Society of Armenia. Ecumenical activities: Programme of Theological Education of WCC, 1984-1988; Central Committee of CEC, 2002-2008; Co-Moderator of Churches in Dialogue of CEC, 2002-2008; Governing Board of CEC, 2013-2018. Hasmik Muradyan works in the Bible Society of Armenia as Translator and Paratext Administrator. Dr. Marianna Apresyan works in the Bible Society of Armenia as EDITORIAL TEAM EDITORIAL Children’s Ministry and Trauma Healing projects coordinator, as lecturer in the Gevorgyan Theological University and as the president of Christian Women Ecumenical Forum in Armenia. The Revd Canon Dr. Leslie Nathaniel is Chaplain of the Anglican Church of St Thomas Becket, Hamburg. Born in South India, he worked with the Archbishop of Canterbury from 2009-2016, initially as the Deputy Secretary for Ecumenical Affairs and European Secretary for the Church of England and later as the Archbishop of Canterbury’s International Ecumenical Secretary. He is the Moderator of the Assembly Planning Committee of the Novi Sad CEC Assembly and was the Moderator of the CEC Assembly Planning Committee in Budapest. -

Baptist Identity and the Ministry of Incarnation a Perspective from Luke Shaw, Past President of the Jamaica Baptist Union

Baptist Identity and the Ministry of Incarnation A perspective from Luke Shaw, past president of the Jamaica Baptist Union “It is not easy to identify the marks of a Baptist community. Whereas certain Christian traditions gain coherence from a shared pattern of worship, or a clear ecclesial structure, or lengthy creedal statements, it is difficult to recognise any such unifying factor for Baptists.”1 An important distinctive of Baptists universally is that we While some basic beliefs and principles which shape are united in Christ worldwide despite our diversity and our identity are articulated on the JBU website2, we join autonomy. Baptists in sharing two basic things with peoples of the world: The Jamaica Baptist Union (JBU), comprised of 338 » Common humanity churches and near 40,000 members, traces its beginning » Shared environment to George Liele, a ‘free black slave’ from Atlanta, Georgia who came to Jamaica in 1783. Beginning in We believe that while being different with different Kingston, his work spread across the island. The Baptist roles, human beings are equally created to lovingly Missionary Society (UK) was invited to support the and responsibly serve each other and our shared work, and in 1814 George Rowe came. The expansion environment. The biblical basis for such belief facilitates of Baptist witness saw both local and British Baptists and defines Baptist distinctives, and enables our fighting towards the emancipation of slaves. Such affirmation of common truths with others. Historically, witness continued in the post-emancipation era, as Baptists have sought to be faithful to the truth of Baptists helped to establish ‘Free Villages’ for the newly the Gospel while patterning early Church principles emancipated, buying large parcels of lands, of which articulated in the New Testament. -

Holy Mount Carmel Missionary Baptist Church Historic Designation Study Report March 2013

HOLY MOUNT CARMEL MISSIONARY BAPTIST CHURCH HISTORIC DESIGNATION STUDY REPORT MARCH 2013 1 HISTORIC DESIGNATION STUDY REPORT March 2013 I. NAME Historic: Holy Mount Carmel Missionary Baptist Church Common Name: Same as above II. LOCATION 2127 West Garfield Avenue Legal Description - Tax Key No. 3500854110 CONTINUATION OF BROWN’S ADD’N IN NW ¼ SEC 19-7-22 BLOCK 230 LOTS 1 THRU 16 & LOTS 25 THRU 30 & PART LOTS 17 THRU 19 COM NE COR LOT 17-TH S 52’-TH NWLY TO PT ON N LILOT19 & 18’ W OF NE COR SD LOT 19-TH E 78’ TO COM & ALL VAC NLY E-W ALLEY & ALL VAC N-S ALLEY LYING N OF LI 5’ N OF S LI LOTS 15 & 25 TID #65 III. CLASSIFICATION Site IV. OWNER Holy Mt Carmel Missionary Baptist Church Inc. C/O Rev Betty S. Hayes 4519A North 37th Street Milwaukee, WI 53209 ALDERMAN Ald. Willie L. Hines, Jr. 15th Aldermanic District NOMINATOR Minister Willie B. Doss V. YEAR BUILT 1989-1991 (Milwaukee Building Permits) ARCHITECT: Jim Schaefer/Schaefer Architects (Milwaukee Building Permits) VI. PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION THE AREA Holy Mount Carmel Church occupies most of the block bounded by West Lloyd Street, North 21st Street, North 22nd Street and West Garfield Avenue. Three residential structures are situated at the south end of the block. The neighborhood is characterized by frame residences built in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Brown Street Academy stands a block to the south and the North Avenue commercial district is located to the north. A swath of large vacant parcels running southeast to northwest and proceeding west parallel to North Avenue marks the path of a freeway project that was not completed. -

The Missionary Dream 1820–1842 85

1 The Missionary᪐ Dream 1820–1842 In the Knibb Baptist Chapel in Falmouth, Jamaica, an impressive marble monument hangs on the wall behind the communion table. As the Baptist Herald reported in February 1841: The emancipated Sons of Africa, in connexion with the church under the pastoral care of the Rev. W. Knibb, have recently erected in this place of worship a splendid marble monument, designed to perpetuate the remem- brance of the glorious period when they came into the possession of that liberty which was their right, and of which they have proved themselves to be so pre-eminently worthy. It is surmounted with the figure of Justice, holding in her left hand the balances of equity, whilst her right hand rests upon the sword which is placed at her side. Beneath this figure the like- nesses of Granville Sharp, Sturge, and Wilberforce are arrayed in bas-relief, and that of the Rev. W. Knibb appears at the base. The inscription reads: deo gloria erected by emancipated sons of africa to commemorate the birth-day of their freedom august the first 1838 hope hails the abolition of slavery throughout the british colonies as the day-spring of universal liberty to all nations of men, whom god “hath made of one blood” “ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands unto god” lxviii psalm 31 verse The Missionary Dream 1820–1842 85 Immediately under this inscription two Africans are represented in the act of burying the broken chain, and useless whip – another is rejoicing in the undisturbed possession of the book of God, whilst associated with these, a fond mother is joyously caressing the infant which for the first time she can dare to regard as her own.