Report on Unemployment/Employment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capitolo 13 Costume Stato E Società

Costume, Stato e Società Costume, Stato e Società Nel V capitolo, intitolato “La Crisi del Trecento”, ho dedicato qualche pagina a descrivere le feste più celebrate dai fiorentini e, in termini sintetici, le condizioni di vita degli uomini del tempo; questo perché una narrazione storica non può del tutto prescindere dagli aspetti legati agli usi e ai costumi. Tuttavia questo tipo di informazioni, se inserite nel contesto, rallentano non poco il racconto; ecco perché ho predisposto questa sezione – intitolata Costume, Stato e Società - dove sono approfonditi alcuni temi e descritti aspetti apparentemente secondari che, uniti alle informazioni del racconto principale, dovrebbero contribuire a dare un quadro più completo della storia cittadina. L’Accademia dei Georgofili e la Società Dantesca Italiana Figura 192: L’Accademia dei Georgofili ed una singolare immagine di Dante Alighieri, in meditazione L’Accademia dei Georgofili nasce a Pitti il 4 giugno 1753, ebbe stanza nella Sala Leone X di Palazzo Vecchio e dal 1933 è alloggiata fra gli Uffizi e la Torre del Pulci dove, in una notte del maggio 1993, ha subito un gravissimo e incredibile attentato, per lo scoppio di una bomba che causò vittime e gravi danni. Due fattori favorirono la nascita e lo sviluppo dei Georgofili: il sostegno del Granduca Pietro Leopoldo I cultore degli studi scientifici e l’affermarsi in Italia delle teorie fisiocratiche che consideravano l’agricoltura base dell’economia e della ricchezza. Al suo tavolo si discussero, nel Settecento, i problemi del commercio del grano, del 286 Costume, Stato e Società libero scambio, della mezzadria, dell’allevamento, delle bonifiche e dell’istruzione agraria. -

ICIAM Newsletter Vol. 2, No. 2, April 2014

Managing Editor Reporters C. Sean Bohun Iain Duff University of Ontario STFC Rutherford Appleton ICIAM Institute of Technology Laboratory Faculty of Science Harwell Oxford 2000 Simcoe St. North Didcot, OX11 OQX, UK Oshawa, ON, Canada e-mail: iain.duff@stfc.ac.uk e-mail: [email protected] Maria J. Esteban CEREMADE Editor-in-Chief Place du Maréchal Lattre de Tassigny Barbara Lee Keyfitz F-75775 Paris Cedex 16, The Ohio State University France Department of Mathematics e-mail: [email protected] 231 West 18th Avenue Columbus, OH 43210-1174 Eunok Jung The ICIAM Dianoia e-mail: bkeyfi[email protected] Konkuk University Department of Mathematics Vol. 2, No. 2, April 2014 Editorial Board 1, Hwayang-dong, Gwangjin-gu Thirty years of SMAI: 1983–2013 — Thierry James M. Crowley Seoul, South Korea Horsin 2 SIAM e-mail: [email protected] ICIAM 2015 Call for Mini-symposia 4 e-mail: [email protected] Abel Prize 2014 Press Release 5 Alexander Ostermann 2016 CIMPA Research Schools Call for Projects 6 University of Innsbruck Thierry Horsin ICSU and ICIAM — Tom Mitsui 6 CNAM, Paris, France Numerical Analysis Group ICIAM 2015 Call for Proposals of Satellite Meet- Département Ingénierie Department of Mathematics ings 8 Mathématique Technikerstraße 13/7 ICIAM, Past and Future: A Conversation Be- e-mail: [email protected] 6020 Innsbruck, Austria tween Two Former Presidents — Olavi e-mail: [email protected] Pammy Manchanda Nevanlinna 8 Guru Nanak Dev University Néstor Thome The ICIAM Officers Meeting — Barbara Keyfitz 11 Amritsar, Punjab, India Universitat Politèchnica di ICIAM Workshop in May 12 Department of Mathematics València Call for Nominations for ICIAM Officers: Secre- e-mail: [email protected] Departamento de Matemática tary, Treasurer, Officer-at-Large 13 Roberto Natalini Aplicada Save the Date! 14 e-mail: [email protected] Consiglio Nazionale delle Invited Speakers of ICIAM 2015 15 Ricerche, Rome, Italy, About ICIAM 16 Istituto per le Applicazioni del Calcolo “M. -

The President's Annual Report Spring 1998

EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE The President’s Annual Report Spring 1998 Report on calendar year 1997, published in Spring 1998 Contents Introduction by the President, Dr Patrick Masterson . 5 The Department of History and Civilization . 9 The Department of Economics. 13 The Department of Law . 18 The Department of Political and Social Sciences . 24 The Robert-Schuman-Centre . 29 The European Forum . 35 Research Student Developments . 37 Events. 46 People . 48 Publications by Staff Members . 50 Physical Developments . 58 Funding of the EUI . 59 The Institute’s Governing Bodies . 61 3 The European University for postgraduate research in the social sciences 4 he purpose of this Annual Report is to provide a concise account of the activities of the European University T Institute during 1997 in the fulfillment of its mission to contribute to the scientific and cultural heritage of Europe through high level research and doctorate formation. The very satisfactory progress of recent years in doctorate thesis completion was significant- ly advanced this year – 85 theses were suc- cessfully defended before international juries – a clear indication of the manner in which our young researchers meet the challenges as well as the opportunity of the Institute’s de- manding standards and multi-cultural context. This is by far the highest annual number of thesis defenses and represents more than twice the number defended five years ago. In the same period the number of students com- pleting their theses in under four years has also doubled. The number of students applying for the 120 Dr Patrick Masterson, President of the EUI first year places was of the order of 1,600. -

Best Practice in Urban Development

Firenze, Italy Opening up the prison The regeneration of the ancient prison complex of Le Murate in the historical centre of Florence is a successful experience of integrated planning, which has restored an area that has historically been cut off from the urban and social fabric of the Santa Croce neighbourhood. The project is based on the city council’s consistent support for a redevelopment which has brought social housing back into the city centre, while also providing new public spaces and pedestrian access routes, an innovative enterprise incubator, an art centre, studios and commercial space. Opening up the prison The regeneration of the ancient prison complex of Le Murate in the historical centre of Florence is a successful experience of integrated planning, which has restored an area that has historically been cut off from the urban and social fabric of the Santa Croce neighbourhood. The project is based on the city council’s consistent support for a redevelopment which has brought social housing back into the city centre, while also developing a multi-sectoral range of interventions including new public spaces and pedestrian access routes, an innovative enterprise incubator, an art centre and studios, as well as commercial space. The project has had a long gestation; since the 1990s, it has been the object of design competitions and of a study by Renzo Piano, who provided the first guidelines for the redevelopment. Work started in 1995 when a consistent national funding source was made available for social housing, and since then the Office for Social Housing (ERP) of the Municipality of Florence has managed the job. -

Istituto Storico Toscano Della Resistenza E Dell'età Contemporanea (ISRT)

ISTITUTO STORICO TOSCANO DELLA RESISTENZA E DELL’ETÀ CONTEMPORANEA BARILE, PAOLO 1939 - 2000, La grande maggioranza dei documenti copre l'arco cronologico 1960-2000. Inventario a cura di Marta Bonsanti (2019) Biografia. Nasce a Bologna il 10 settembre 1917. Nel 1939 si laurea in giurisprudenza a Roma con il pro- fessor Salvatore Messina e diviene assistente ordinario per gli anni accademici successivi, che peraltro trascorre in servizio militare essendo stato chiamato alle armi nel 1939. Nel 1941 vince il primo posto del concorso in Magistratura ordinaria e prende servizio nel 1943 presso il Tribunale militare di Trieste e successivamente presso il Tribunale di Firenze e poi quello di Pistoia. Dopo aver aderito nel 1941 al movimento liberal-socialista, nel gruppo romano di Federico Comandini, nel 1943 entra nel Partito d'a- zione e nelle file di questo, in seguito al suo rientro a Firenze dopo l'8 settembre, partecipa attivamente alla Resistenza. Tra i dirigenti del Comitato militare del Comitato toscano di liberazione nazionale, nel novembre è catturato insieme ad Adone Zoli ed altri dalla polizia del famigerato Mario Carità; torturato a Villa Triste e portato in ospedale per una pugnalata alla testa, insieme agli altri prigionieri è reclamato dal comando tedesco e trasferito nel carcere militare della Fortezza da Basso. Nonostante le insistenti richieste di fucilazione avanzate dai fascisti come rappresaglia per l'attentato al tenente colonnello Gobbi, Barile e gli altri membri del Comitato militare sono rilasciati con l'obbligo di presentarsi settimanalmente. A Barile si dà alla macchia e riprende la sua attività nella Resistenza fiorentina a fianco degli azionisti. -

ICIAM Newsletter Vol. 1, No. 2, April 2013

Editorial Team ICIAM Officers Managing Editor President C. Sean Bohun Barbara Lee Keyfitz ICIAM University of Ontario The Ohio State University Institute of Technology Department of Mathematics Faculty of Science 231 West 18th Avenue 2000 Simcoe St. North Columbus, OH 43210-1174 Oshawa, ON, Canada e-mail: bkeyfi[email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Past-President Reporters Rolf Jeltsch James M. Crowley ETH Zürich, Seminar for SIAM Applied Mathematics e-mail: [email protected] CH-8092 Zürich, Switzerland e-mail: [email protected] Iain Duff The ICIAM Newsletter STFC Rutherford Appleton Laboratory Secretary Vol. 1, No. 2, April 2013 e-mail: iain.duff@stfc.ac.uk Alistair Fitt The ICIAM Newsletter — Barbara Lee Keyfitz 2 Maria J. Esteban Oxford Brookes University What is the Name of this Newsletter? 3 CEREMADE Headington Campus A Report on a Satellite Conference of ICM 2010 e-mail: [email protected] Gipsy Lane — A. H. Siddiqi 3 Eunok Jung Oxford, OX3 0BP, UK e-mail: afi[email protected] Changes to the By-Laws — Barbara Lee Keyfitz 5 Konkuk University Workshop on Applications of Mathematics to Department of Mathematics Industry — David Marques Pastrelo 6 e-mail: [email protected] Treasurer ICIAM 2015: Call for Proposals of Thematic and Roberto Natalini José A Cuminato Industrial Minisymposia 7 Istituto per le Applicazioni University of Sao Paulo at Workshop on Mathematics of Climate Change, del Calcolo Sao Carlos Related Hazards and Risks 7 Dip. di Matematica, Department of Applied US National Research Council Issues Report on Università di Roma Mathematics and Statistics the Mathematical Sciences 8 e-mail: [email protected] P.O. -

Good Practice in Urban Development

Firenze, Italy BACKGROUND INFORMATION PROJECT TITLE Le Murate – Urban Park for Innovation Beneficiary Beneficiary of the funding is the Municipality of Florence as direct manager of the project. Duration of project 2010-2014 (current phase of implementation). The whole redevelopment project was initiated in 1996. Member State Italia, Regione Toscana, Firenze Geographic size The area measures about 13 000 m². The Municipality of Florence has a population of 373 446. Florence FUA 645 000. Florence Polycentric Metropolitan Area 1 090 000. Funding The project in the first phase received funding of about 26 million € from national/local funds for housing. In the current phase: Innovation park: 430 000 € Road link: 260 000 € Total ERDF funding: 690 000 € Operational Operational Programme Tuscany - “POR CReO” (Creativity and Innovation) Programme CCI no: 2007IT162PO012 Priority 5: Making full use of local resources, sustainable development of the territory [about 24.5% of total investment] Managing Authority Regione Toscana Directorate General for Economic Development Via di Novoli 26 I-50127 Firenze Regional level (NUTS 2) Cohesion Policy Obj. Competitiveness Main reason for The approach is in line with art. 8 in addressing area-based integrated regeneration. It is Highlighting this case not directed to a typically ‘deprived area’, as Santa Croce is a valuable neighbourhood experiencing global dynamics such as tourism and gentrification, but the area-based concentration of actions and funds aims to balance exclusionary dynamics with provision of affordable social housing, cultural activities, social services and public space. The case study is interesting also because involves a policy framework developed by the Regione Toscana particularly in line with the EU Urban Acquis, which includes an Integrated Plan for Sustainable Urban Development (PIUSS) designed in the framework of the ERDF Operational Programme. -

ICIAM Newsletter Vol. 3, No. 3, July 2015

Managing Editor Reporters ICIAM C. Sean Bohun Iain Duff University of Ontario STFC Rutherford Appleton Institute of Technology Laboratory Faculty of Science Harwell Oxford 2000 Simcoe St. North Didcot, OX11 OQX, UK Oshawa, ON, Canada e-mail: iain.duff@stfc.ac.uk e-mail: [email protected] Maria J. Esteban CEREMADE Editor-in-Chief Place du Maréchal Lattre de Tassigny Barbara Lee Keyfitz F-75775 Paris Cedex 16, The Ohio State University France Department of Mathematics e-mail: [email protected] The ICIAM Dianoia 231 West 18th Avenue Columbus, OH 43210-1174 Eunok Jung Vol. 3, No. 3, July 2015 e-mail: bkeyfi[email protected] Konkuk University Department of Mathematics EDITORIAL: Mathematics and Money, PR and Editorial Board 1, Hwayang-dong, Gwangjin-gu Professionalism — Barbara Lee Keyfitz 2 Systems Anaylsis 2015 4 James M. Crowley Seoul, South Korea Abel Prize 2016 Call for Nominations 5 SIAM e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Report from CAIMS*SCMAI — Raymond Spiteri 5 Alexander Ostermann Announcement of MCA-2017 6 Thierry Horsin University of Innsbruck Silver Jubilee of the Indian Society of Industrial CNAM, Paris, France Numerical Analysis Group and Applied Mathematics 7 Département Ingénierie Department of Mathematics A Research School in Morocco — Mohammed Mathématique Technikerstraße 13/7 Rhoudaf 8 e-mail: [email protected] 6020 Innsbruck, Austria Call for Nominations for The Felix Klein Prize 9 e-mail: [email protected] Pammy Manchanda CIMPA, an opportunity — Maria J. Esteban 9 Guru Nanak Dev University Tomás Chacón Rebollo Call for Nominations for ICIAM Officers 11 Amritsar, Punjab, India Universidad de Sevilla Car — Jim Talamo 11 Department of Mathematics Departamento de The ICIAM Officers Meeting: May 2015 e-mail: [email protected] Ecuaciones Diferenciales y — Barbara Lee Keyfitz 12 Recent News from the International Council for Roberto Natalini Análisis Numérico e-mail: [email protected] Consiglio Nazionale delle Science 13 About ICIAM 14 Ricerche, Rome, Italy, Istituto per le Applicazioni del Calcolo “M. -

CV Mario Primicerio Studies University Positions Academic

CV Mario Primicerio Studies Birth date: 13 November 1940 Birth place: Rome (Italy) Married, 1 son Degree in Physics (Laurea), University of Florence, November 1962 Military Service: Military Geographic Institute (Oct. 1967, Dec. 1968). University Positions Researcher (1963) at the Ionized Gases Laboratory, Frascati (Rome) Assistant Professor (since 1967) and Associate Professor (since 1970) at the University of Florence Full Professor ( Rational Mechanics and Applied Mathematics) at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Florence (since 1975). Emeritus Professor (since 2012) Academic duties Chairman of the Corso di Laurea in Matematica (1978 - 79) Adjoint of the Rector for the International Relationships of the University (1983 - 1991) Dean of the Faculty of Sciences (1984 - 87) Member of the Governing Board of the Department of Mathematics (1990 - 95) Chairman of the Graduate School in Mathematics 1993 - 95 and 2002-2010 Direction and/or co-direction of major research projects U.S.A.E.R.O.: "Free Boundary Problems in Diffusion with Mass Transfer" (1982 - 84) European Community: "Mathematical Models of Phase Transitions and Numerical Simulation" (1987-88) SNAMPROGETTI/ENIRICERCHE/University of Florence: "Rheology of Concentrated Coal-Water Suspensions" (1988 - 1992) C.N.R. : "Nonlinear Filtration and Applications" (1990 - 91) European Consortium for Mathematics in Industry: "Mathematical Models for Percolation of Coffee" (1991-96 ) U.S.A.E.R.O.: "Ground freezing" (1992-95) European Science Foundation: "Free Boundary Problems and -

ICIAM Newsletter Vol. 2, No. 3, July 2014

ICIAM Managing Editor Reporters C. Sean Bohun Iain Duff University of Ontario STFC Rutherford Appleton Institute of Technology Laboratory Faculty of Science Harwell Oxford 2000 Simcoe St. North Didcot, OX11 OQX, UK Oshawa, ON, Canada e-mail: iain.duff@stfc.ac.uk e-mail: [email protected] Maria J. Esteban CEREMADE Editor-in-Chief Place du Maréchal Lattre de Tassigny Barbara Lee Keyfitz F-75775 Paris Cedex 16, The ICIAM Dianoia The Ohio State University France Vol. 2, No. 3, July 2014 Department of Mathematics e-mail: [email protected] 231 West 18th Avenue The 2014 ICIAM Scientific Workshop and Board Columbus, OH 43210-1174 Eunok Jung Meeting — Barbara Lee Keyfitz 2 e-mail: bkeyfi[email protected] Konkuk University Department of Mathematics ICIAM 2015 Call for Proposals of Satellite Meetings 3 Editorial Board 1, Hwayang-dong, Gwangjin-gu PRESS RELEASE: Éva Tardos to deliver Olga Taussky-Todd Lecture, ICIAM 2015 3 James M. Crowley Seoul, South Korea ICIAM, Past and Future: A Conversation SIAM e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Between Two Former Presidents — Olavi Alexander Ostermann Nevanlinna 5 Thierry Horsin University of Innsbruck Call for Nominations for ICIAM Officers: CNAM, Paris, France Numerical Analysis Group Secretary, Treasurer, Officers-at-Large 7 Département Ingénierie Department of Mathematics GAMM Juniors’ Summer School 8 Mathématique Technikerstraße 13/7 Mathematics and the Complexity of the Earth e-mail: [email protected] 6020 Innsbruck, Austria System — Maria J. Esteban 9 e-mail: [email protected] -

La Grande Alluvione

TESTIM IN QUESTO NUMERO La grande alluvione (Volume monografico speciale a cura di Giorgio Valentino Federici, Miriana Meli, o Lucio Niccolai, Severino Saccardi, Simone Siliani, Vincenzo Striano) NIANZE TESTIM NIANZE Rivista fondata da Ernesto Balducci La grande alluvione o Ernesto Balducci A 50 anni dall’alluvione del 1966 Severino Saccardi; Giorgio Valentino Federici; Dario Nardella; Enrico Rossi; Eugenio Giani Quei giorni a Firenze Antonina Bargellini; Ignazio Becchi; Fabio Dei; Anna Iuso; Ignazio Becchi; Erasmo D’Angelis; Franco Quercioli; Mauro Sbordoni; Sandra Teroni; Valeria D’Agostino; Piero Meucci; Mario Primicerio, Severino Saccardi e Simone Siliani; Giorgio La Pira; Redazione di «Testimonianze»; Aldo Buoncristiano; Filppo Vannoni; Roberto Mosi; Adriana Billi; Silvia Costa; Claudia Petrucci; La grande Mauro Cozzi; Luca Brogioni; Erika Ghilardi Quei giorni in Toscana Lucio Niccolai; Velio Abati e Lucio Niccolai; Alessandro Angeli; Alessandro Angeli; Corrado Barontini; Pietro Piussi e Giampietro Wirz; Stefano Beccastrini; Pier Angelo Bonazzoli, Davide Giovannuzzi e Andrea Rossi; Paolo Capezzone; Remo Chiarini; Giorgio Valentino Federici e Lorenzo Giudici; Miriana Meli; Sandro Bennucci alluvione Beni culturali e restauro: il «laboratorio Firenze» Cristina Acidini; Marco Ciatti; Gisella Guasti; Carla Guiducci Bonanni e Luca Nannipieri; Giulia Coco e Magnolia Scudieri; Giuseppe De Micheli; Irene Foraboschi e Anna Mieli; Loredana Maccabruni Il Progetto «Firenze2016» - «Toscana2016» Francesco Alberti e Marco Massa; Giuliano Bianucci; Concetta Bianca; Michele Ercolini; Simona Francalanci, Enio Paris e Luca Solari; Lorenzo Giudici; Francesco Niccolini; Salvatore Siano; Vincenzo Striano; Giuseppe Vallario Ripensare l’alluvione, a scuola Studenti della classe 4ªG del Liceo scientifico «Il Pontormo» di Empoli (coordinati dal prof. Paolo Capezzone); Studenti della classe 5ªC del Liceo scientifico «L. -

Preliminary Proposal to IAP

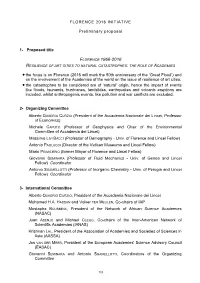

FLORENCE 2016 INITIATIVE Preliminary proposal 1- Proposed title FLORENCE 1966-2016 RESILIENCE OF ART CITIES TO NATURAL CATASTROPHES: THE ROLE OF ACADEMIES • the focus is on Florence (2016 will mark the 50th anniversary of the ‘Great Flood’) and on the involvement of the Academies of the world on the issue of resilience of art cities; • the catastrophes to be considered are of ‘natural’ origin, hence the impact of events like floods, tsunamis, hurricanes, landslides, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions are included, whilst anthropogenic events, like pollution and war conflicts are excluded. 2- Organizing Committee Alberto QUADRIO CURZIO (President of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Professor of Economics) Michele CAPUTO (Professor of Geophysics and Chair of the Environmental Committee of Accademia dei Lincei) Massimo LIVI BACCI (Professor of Demography - Univ. of Florence and Lincei Fellow) Antonio PAOLUCCI (Director of the Vatican Museums and Lincei Fellow) Mario PRIMICERIO (former Mayor of Florence and Lincei Fellow) Giovanni SEMINARA (Professor of Fluid Mechanics - Univ. of Genoa and Lincei Fellow) Coordinator Antonio SGAMELLOTTI (Professor of Inorganic Chemistry - Univ. of Perugia and Lincei Fellow) Coordinator 3- International Committee Alberto QUADRIO CURZIO, President of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei Mohamed H.A. HASSAN and Volker TER MEULEN, Co-chairs of IAP Mostapha BOUSMINA, President of the Network of African Science Academies (NASAC) Juan ASENJO and Michael CLEGG, Co-chairs of the Inter-American Network of Scientific Academies (IANAS) Krishnan LAL, President of the Association of Academies and Societies of Sciences in Asia (AASSA) Jos VAN DER MEER, President of the European Academies' Science Advisory Council (EASAC) Giovanni SEMINARA and Antonio SGAMELLOTTI, Coordinators of the Organizing Committee 1/3 4- Date 11 - 12 October 2016 5- Venue Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Palazzo Corsini, Rome 6- Structure of the meeting We propose the following structure of the meeting.