Effect of Community-Based Health Insurance on Healthcare-Seeking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Midterm Survey Protocol

Protocol for L10K Midterm Survey The Last 10 Kilometers Project JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia October 2010 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 The Last Ten Kilometers Project ............................................................................................................ 3 Objective one activities cover all the L10K woredas: .......................................................................... 4 Activities for objectives two, three and four in selected woredas ...................................................... 5 The purpose of the midterm survey ....................................................................................................... 6 The midterm survey design ...................................................................................................................... 7 Annex 1: List of L10K woredas by region, implementation strategy, and implementing phase ......... 10 Annex 2: Maps.................................................................................................................................................. 11 Annex 3: Research questions with their corresponding study design ...................................................... 14 Annex 4: Baseline survey methodology ........................................................................................................ 15 Annex 5: L10K midterm survey -

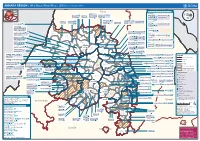

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

English-Full (0.5

Enhancing the Role of Forestry in Building Climate Resilient Green Economy in Ethiopia Strategy for scaling up effective forest management practices in Amhara National Regional State with particular emphasis on smallholder plantations Wubalem Tadesse Alemu Gezahegne Teshome Tesema Bitew Shibabaw Berihun Tefera Habtemariam Kassa Center for International Forestry Research Ethiopia Office Addis Ababa October 2015 Copyright © Center for International Forestry Research, 2015 Cover photo by authors FOREWORD This regional strategy document for scaling up effective forest management practices in Amhara National Regional State, with particular emphasis on smallholder plantations, was produced as one of the outputs of a project entitled “Enhancing the Role of Forestry in Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy”, and implemented between September 2013 and August 2015. CIFOR and our ministry actively collaborated in the planning and implementation of the project, which involved over 25 senior experts drawn from Federal ministries, regional bureaus, Federal and regional research institutes, and from Wondo Genet College of Forestry and Natural Resources and other universities. The senior experts were organised into five teams, which set out to identify effective forest management practices, and enabling conditions for scaling them up, with the aim of significantly enhancing the role of forests in building a climate resilient green economy in Ethiopia. The five forest management practices studied were: the establishment and management of area exclosures; the management of plantation forests; Participatory Forest Management (PFM); agroforestry (AF); and the management of dry forests and woodlands. Each team focused on only one of the five forest management practices, and concentrated its study in one regional state. -

Ethiopia: Amhara Region Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Amhara region administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abrha jara ! Tselemt !Adi Arikay Town ! Addi Arekay ! Zarima Town !Kerakr ! ! T!IGRAY Tsegede ! ! Mirab Armacho Beyeda ! Debark ! Debarq Town ! Dil Yibza Town ! ! Weken Town Abergele Tach Armacho ! Sanja Town Mekane Berhan Town ! Dabat DabatTown ! Metema Town ! Janamora ! Masero Denb Town ! Sahla ! Kokit Town Gedebge Town SUDAN ! ! Wegera ! Genda Wuha Town Ziquala ! Amba Giorges Town Tsitsika Town ! ! ! ! Metema Lay ArmachoTikil Dingay Town ! Wag Himra North Gonder ! Sekota Sekota ! Shinfa Tomn Negade Bahr ! ! Gondar Chilga Aukel Ketema ! ! Ayimba Town East Belesa Seraba ! Hamusit ! ! West Belesa ! ! ARIBAYA TOWN Gonder Zuria ! Koladiba Town AMED WERK TOWN ! Dehana ! Dagoma ! Dembia Maksegnit ! Gwehala ! ! Chuahit Town ! ! ! Salya Town Gaz Gibla ! Infranz Gorgora Town ! ! Quara Gelegu Town Takusa Dalga Town ! ! Ebenat Kobo Town Adis Zemen Town Bugna ! ! ! Ambo Meda TownEbinat ! ! Yafiga Town Kobo ! Gidan Libo Kemkem ! Esey Debr Lake Tana Lalibela Town Gomenge ! Lasta ! Muja Town Robit ! ! ! Dengel Ber Gobye Town Shahura ! ! ! Wereta Town Kulmesk Town Alfa ! Amedber Town ! ! KUNIZILA TOWN ! Debre Tabor North Wollo ! Hara Town Fogera Lay Gayint Weldiya ! Farta ! Gasay! Town Meket ! Hamusit Ketrma ! ! Filahit Town Guba Lafto ! AFAR South Gonder Sal!i Town Nefas mewicha Town ! ! Fendiqa Town Zege Town Anibesema Jawi ! ! ! MersaTown Semen Achefer ! Arib Gebeya YISMALA TOWN ! Este Town Arb Gegeya Town Kon Town ! ! ! ! Wegel tena Town Habru ! Fendka Town Dera -

International Journal of Advanced Research in Biological Sciences

Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. (2019). 6(2): 110-117 International Journal of Advanced Research in Biological Sciences ISSN: 2348-8069 www.ijarbs.com DOI: 10.22192/ijarbs Coden: IJARQG(USA) Volume 6, Issue 2 - 2019 Research Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22192/ijarbs.2019.06.02.013 A Cross Sectional Study on the Prevalence and Possible Risk Factors of Bovine Schistosomiasis in and Around Gozamen District, Northwest Ethiopia Yezina Mengist1 and Nigussie Yilak2* 1 Gozamen Agricultural Office , East Gojjam, ETHIOPIA 2Shewa Robit Municipal Abattoir, Shewa Robit, ETHIOPIA *Corresponding author: Nigussie Yilak; email: [email protected] Abstract A cross sectional study was conducted from April, 2017 to July 2017 in and around Gozamen district to estimate the prevalence and possible risk factors of bovine Schistosomiasis. Simple random sampling was used to select the study animals and sedimentation technique. Out of 384 faecal samples examined 101(26.3%) were found positive for bovine Schistosomiasis. The prevalence of bovine Schistosomiasis was higher in local breed cattle (29.3%) than cross breed cattle (16.1%). Similarly, the prevalence of the disease in male and female cattle was 26.2% and 26.4%, respectively. Cattle having less than 2 years, 2-5years and greater than 5 years old had (18.8%), (28.7%) and (26.0%) disease prevalence, respectively without significant statistical difference (p>0.05). The highest prevalence of Schistosoma infection was observed in poor body conditioned animals (35.5%) followed by medium body conditioned animals (21.1%). Whereas, the lowest prevalence of the disease was observed in good body conditioned animals (11.4%). -

Defining and Managing Acute Lymphangioadenitis in Podoconiosis Lymphoedema in Northern Ethiopia

DEFINING AND MANAGING ACUTE LYMPHANGIOADENITIS IN PODOCONIOSIS LYMPHOEDEMA IN NORTHERN ETHIOPIA HENOK NEGUSSIE SEIFU PhD 2017 1 DEFINING AND MANAGING ACUTE LYMPHANGIOADENITIS IN PODOCONIOSIS LYMPHOEDEMA IN NORTHERN ETHIOPIA HENOK NEGUSSIE SEIFU A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University of Brighton and the University of Sussex for a programme of study undertaken at Brighton and Sussex Medical School for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy JULY, 2017 2 This thesis was supervised by Prof Gail Davey, Professor of Global Health Epidemiology, Brighton and Sussex Medical Scholl, UK Prof. Melanie Newport, Professor of Global Health and Infection, Brighton and Sussex Medical Scholl, UK Prof Fikre Enquselassie, Professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Addis Ababa, University 3 Abstract Podoconiosis (endemic non-filarial elephantiasis) is a non-infectious disease arising in barefoot individuals in long-term contact with irritant red clay soil of volcanic origin. The condition is believed to be caused by the interplay between environmental factors and genetic susceptibility over a prolonged period of time. In the last decade significant progress had been made in research on podoconiosis. Acute dermatolymphangioadenitis (ADLA) is a common and disabling complication of podoconiosis lymphoedema and remain the most painful and distressing condition, with diverse health, social and economic ramifications, yet has been very little investigated to date. This PhD thesis is therefore, aimed at defining ADLA, validating this to measure the impact of ADLA, and to document the impact of a simple foot hygiene intervention on ADLA and quality of life among podoconiosis patients. The study utilized several steps. -

Download File

Report One size does not fit all The patterning and drivers of child marriage in Ethiopia’s hotspot districts Nicola Jones, Bekele Tefera, Guday Emirie, Bethelihem Gebre, Kiros Berhanu, Elizabeth Presler-Marshall, David Walker, Taveeshi Gupta and Georgia Plank March 2016 This research was conducted by Overseas Development Institute (ODI), contracted by UNICEF in collaboration with the National Alliance to End Child Marriage and FGM in Ethiopia by 2025. UNICEF and ODI hold joint copyright. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policies or views of UNICEF or ODI. UNICEF Ethiopia UNECA Compound, Zambezi Building Tel: +251115184000 Fax: +251115511628 E-mail:[email protected] www.unicef.org/Ethiopia Overseas Development Institute 203 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ Tel. +44 (0) 20 7922 0300 Fax. +44 (0) 20 7922 0399 E-mail: [email protected] www.odi.org www.odi.org/facebook www.odi.org/twitter Readers are encouraged to reproduce material from ODI Reports for their own publications, as long as they are not being sold commercially. As copyright holder, ODI and UNICEF request due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the ODI and UNICEF websites. © Overseas Development Institute and United Nations Children’s Fund 2015. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial Licence (CC BY-NC 3.0). ISSN: 2052-7209 All ODI Reports are available from www.odi.org Cover photo: Hands, Ethiopia -

Ethiopia Social Accountability Program (ESAP3)

Ethiopia Social Accountability Program (ESAP3) Grant Agreement [TF0A9293] Progress Report Project Year 2, Quarter 3 July – September 2020 MANAGEMENT AGENCY Multi Donor Trust Fund Table of contents Table of contents ..................................................................................... 2 List of Acronyms ..................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................... 4 Technical Progress .................................................................................. 5 1. MA main activities .......................................................................................... 5 1.1. COTL support and coordination .......................................................................................... 5 1.2 Resumption of SA activities ................................................................................................. 5 2. SAIP activities ................................................................................................ 5 2.1 Accessing citizens in ESAP operational areas with COVID-19 information through CRs .. 8 2.1.1Dissemination of reliable, factual and up to date COVID-19 information .................... 8 2.1.2 Reaching out to community groups with special needs .............................................. 8 2.1.3 Engaging community leaders and influential citizens .................................................. 9 2.1.4 Using other innovative mechanisms to access -

Woreda-Level Crop Production Rankings in Ethiopia: a Pooled Data Approach

Woreda-Level Crop Production Rankings in Ethiopia: A Pooled Data Approach 31 January 2015 James Warner Tim Stehulak Leulsegged Kasa International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) Addis Ababa, Ethiopia INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) was established in 1975. IFPRI is one of 15 agricultural research centers that receive principal funding from governments, private foundations, and international and regional organizations, most of which are members of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). RESEARCH FOR ETHIOPIA’S AGRICULTURE POLICY (REAP): ANALYTICAL SUPPORT FOR THE AGRICULTURAL TRANSFORMATION AGENCY (ATA) IFPRI gratefully acknowledges the generous financial support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) for IFPRI REAP, a five-year project to support the Ethiopian ATA. The ATA is an innovative quasi-governmental agency with the mandate to test and evaluate various technological and institutional interventions to raise agricultural productivity, enhance market efficiency, and improve food security. REAP will support the ATA by providing research-based analysis, tracking progress, supporting strategic decision making, and documenting best practices as a global public good. DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared as an output for REAP and has not been reviewed by IFPRI’s Publication Review Committee. Any views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or views of IFPRI, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. AUTHORS James Warner, International Food Policy Research Institute Research Coordinator, Markets, Trade and Institutions Division, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia [email protected] Timothy Stehulak, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Research Analyst, P.O. -

Childhood Diarrhea Exhibits Spatiotemporal Variation in Northwest Ethiopia: a Satscan Spatial Statistical Analysis

RESEARCH ARTICLE Childhood Diarrhea Exhibits Spatiotemporal Variation in Northwest Ethiopia: A SaTScan Spatial Statistical Analysis Muluken Azage1*, Abera Kumie2, Alemayehu Worku2, Amvrossios C. Bagtzoglou3 1 Ethiopian Institute of Water Resources, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2 School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 3 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, School of Engineering, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, United States of America * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Background Citation: Azage M, Kumie A, Worku A, Bagtzoglou AC (2015) Childhood Diarrhea Exhibits Childhood diarrhea continues to be a public health problem in developing countries, includ- Spatiotemporal Variation in Northwest Ethiopia: A ing Ethiopia. Detecting clusters and trends of childhood diarrhea is important to designing SaTScan Spatial Statistical Analysis. PLoS ONE 10 effective interventions. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate spatiotemporal clustering (12): e0144690. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144690 and seasonal variability of childhood diarrhea in northwest Ethiopia. Editor: Agricola Odoi, University of South Africa (South Africa) and University of Tennessee (USA), UNITED STATES Methods Received: April 18, 2015 Retrospective record review of childhood diarrhea was conducted using quarterly reported Accepted: November 22, 2015 data to the district health office for the seven years period beginning July 1, 2007. Thirty Published: December 21, 2015 three districts were included and geo-coded in this study. Spatial, temporal and space-time scan spatial statistics were employed to identify clusters of childhood diarrhea. Smoothing Copyright: This is an open access article, free of all copyright, and may be freely reproduced, distributed, using a moving average was applied to visualize the trends and seasonal pattern of child- 1 transmitted, modified, built upon, or otherwise used hood diarrhea. -

Journal of Community Medicine & Public Health

Journal of Community Medicine & Public Health Chanie T. J Community Med Public Health 1: 103. Research Article DOI: 10.29011/2577-2228.100003 Knowledge, and Practice on the Importance of Shoe Wearing to Pre- vent Podoconiosis and Its Associated Factors among Households in the Rural Community of Aneded District, North West Ethiopia, 2015 Tenaw Chanie* Department of Public Health University, JSI-L10K Research and Training Inc. Institute, Ethiopia *Corresponding author: Tenaw Chanie, Department of Public Health University, JSI-L10K Research and Training Inc. Institute, Ethiopia. Tel: +2510582221270; Fax: +2510582262403; Email: [email protected] Citation: Chanie T (2017) Knowledge, and Practice on the Importance of Shoe Wearing to Prevent Podoconiosis and Its Associated Factors among Households in the Rural Community of Aneded District, North West Ethiopia, 2015. J Community Med Public Health 1: 103. DOI: 10.29011/2577-2228.100003 Received Date: 14 July, 2017; Accepted Date: 06 September, 2017; Published Date: 13 September, 2017 Abstract Introduction: Podoconiosis infection is one of the NTDs occurring among barefoot people in areas of extreme poverty. It pro- motes poverty through effects on education, economic productivity and disability. It is estimated up to one million cases exist in Ethiopia. Promotion of consistent shoe-wearing practices have advantages in controlling podoconiosis. Better understanding of the behaviors influencing use of footwear will lead to improved ability to measure shoe wearing practice and will be important for those implementing footwear programs. But, many practical and social barriers prevented the desire to wear shoes from being translated into practice. Objective: The aim of this study is to assess knowledge and practice of Aneded district rural community on the importance of shoe wearing to prevent Podoconiosis and its associated factors North West Ethiopia.