Research Paper on PSNP and HABP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Midterm Survey Protocol

Protocol for L10K Midterm Survey The Last 10 Kilometers Project JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia October 2010 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 The Last Ten Kilometers Project ............................................................................................................ 3 Objective one activities cover all the L10K woredas: .......................................................................... 4 Activities for objectives two, three and four in selected woredas ...................................................... 5 The purpose of the midterm survey ....................................................................................................... 6 The midterm survey design ...................................................................................................................... 7 Annex 1: List of L10K woredas by region, implementation strategy, and implementing phase ......... 10 Annex 2: Maps.................................................................................................................................................. 11 Annex 3: Research questions with their corresponding study design ...................................................... 14 Annex 4: Baseline survey methodology ........................................................................................................ 15 Annex 5: L10K midterm survey -

Determinants of Rural Household's Livelihood Strategies in Machakel Woreda, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Nation Regional State, Ethiopia

Developing Country Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-607X (Paper) ISSN 2225-0565 (Online) Vol.8, No.10, 2018 Determinants of Rural Household's Livelihood Strategies in Machakel Woreda, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Nation Regional State, Ethiopia Adey Belete Department of Disaster Risk Management & Sustainable Development, Institute of Disaster Risk Management & Food Security Studies, Bahir Dar University, P.O.Box 5501 Abstract Rural farm households face an increasing need of looking for alternative income sources to supplement their small scale agricultural activities. However, livelihood strategy is determined by complex and yet empirically untested factors in Machakel Woreda. Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the determinants of livelihood strategies in the study area. The data were obtained from 144 sample household heads that were selected through a combination of multi-stage sampling like purposive and simple random sampling techniques. Data were collected through key informant interview, focus group discussion and interview schedule. Multinomial logistic regression model used to analyze determinants of livelihood strategies. Data analysis revealed that farm alone activities has a leading contribution to the total income of sample households (69.8%) followed by non-farm activities (17.2%) and off- farm activities (13 %.). Crop production was the dominant livelihood in the study area and land fragmentation, decline in productivity, occurrence of disaster risk like crop and livestock disease, hail storm, flash flood etc. and market fluctuation were major threatens of livelihood. Four livelihood strategies namely farm alone, farm plus non-farm, farm plus off-farm and farm plus non-farm plus off-farm were identified. Age, education level, sex of household head, marital status, credit access, farm land size, livestock holding size , agro-ecology, family size, frequency of extension contact, distance from market and total net income were major determinants of livelihood strategies in the study area. -

Food Insecurity Among Households with and Without Podoconiosis in East and West Gojjam, Ethiopia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online Food insecurity among households with and without podoconiosis in East and West Gojjam, Ethiopia Article (Published Version) Ketema, Kassahun, Tsegay, Girmay, Gedle, Dereje, Davey, Gail and Deribe, Kebede (2018) Food insecurity among households with and without podoconiosis in East and West Gojjam, Ethiopia. EC Nutrition, 13 (7). pp. 414-423. ISSN 2453-188X This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/76681/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. -

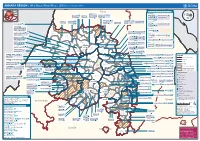

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Farmers' Varietal Selection of Food Barley Genotypes in Gozamin

American-Eurasian J. Agric. & Environ. Sci., 17 (3): 232-238, 2017 ISSN 1818-6769 © IDOSI Publications, 2017 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.aejaes.2017.232.238 Farmers’ Varietal Selection of Food Barley Genotypes in Gozamin District of East Gojjam Zone, Northwestern Ethiopia Yalemtesfa Firew Guade Department of Horticulture, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Debre Markos University, Ethiopia Abstract: In this study, the performance of four improved food barley varieties obtained from Holleta Agricultural Research Center and local variety collected from the study area were evaluated in randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three replications under farmers’ participatory selection scheme during 2016 main cropping season in Gozamin district, East Gojjam Zone, Northwestern Ethiopia. The objectives of this study were to select adaptable and high yielding food barley genotype(s) using farmers’ preferences and to identify farmers’ preference and selection criteria of the study area. Farmers’ set; grain yield, early maturity, tillering ability and spike length as their selection criteria at maturity stage of the crop. The results of analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated significant differences among genotypes for all traits tested except number of effective tillers and thousand seed weight which were non-significant at 5% probability level. The improved variety EH-1493 (133 days) was the earliest while local variety (142 days) was the latest. The highest mean grain yield was obtained from HB-1307 (3700 kg ha-1 ) and Cross-41/98 (3133 kg ha-1 ) whereas the lowest from the local variety (1693 kg ha 11). Similarly, HB-1307(5033 kg ha ) and Cross-41/98 (3633.33 kg ha 1) had given comparatively the highest above ground biomass yield which was used as a source of feed for animals. -

Farmers Willingness to Participate in Voluntary Land Consolidation in Gozamin District, Ethiopia

land Article Farmers Willingness to Participate In Voluntary Land Consolidation in Gozamin District, Ethiopia Abebaw Andarge Gedefaw 1,2,* , Clement Atzberger 1 , Walter Seher 3 and Reinfried Mansberger 1 1 Institute of Surveying, Remote Sensing and Land Information, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Peter-Jordan-Strasse 82, 1190 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] (C.A.); [email protected] (R.M.) 2 Institute of Land Administration, Debre Markos University, 269 Debre Markos, Ethiopia 3 Institute of Spatial Planning, Environmental Planning and Land Rearrangement, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Peter-Jordan-Strasse 82, 1190 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 10 September 2019; Accepted: 10 October 2019; Published: 12 October 2019 Abstract: In many African countries and especially in the highlands of Ethiopia—the investigation site of this paper—agricultural land is highly fragmented. Small and scattered parcels impede a necessary increase in agricultural efficiency. Land consolidation is a proper tool to solve inefficiencies in agricultural production, as it enables consolidating plots based on the consent of landholders. Its major benefits are that individual farms get larger, more compact, contiguous parcels, resulting in lower cultivation efforts. This paper investigates the determinants influencing the willingness of landholder farmers to participate in voluntary land consolidation processes. The study was conducted in Gozamin District, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. The study was mainly based on survey data collected from 343 randomly selected landholder farmers. In addition, structured interviews and focus group discussions with farmers were held. The collected data were analyzed quantitatively mainly by using a logistic regression model and qualitatively by using focus group discussions and expert panels. -

English-Full (0.5

Enhancing the Role of Forestry in Building Climate Resilient Green Economy in Ethiopia Strategy for scaling up effective forest management practices in Amhara National Regional State with particular emphasis on smallholder plantations Wubalem Tadesse Alemu Gezahegne Teshome Tesema Bitew Shibabaw Berihun Tefera Habtemariam Kassa Center for International Forestry Research Ethiopia Office Addis Ababa October 2015 Copyright © Center for International Forestry Research, 2015 Cover photo by authors FOREWORD This regional strategy document for scaling up effective forest management practices in Amhara National Regional State, with particular emphasis on smallholder plantations, was produced as one of the outputs of a project entitled “Enhancing the Role of Forestry in Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy”, and implemented between September 2013 and August 2015. CIFOR and our ministry actively collaborated in the planning and implementation of the project, which involved over 25 senior experts drawn from Federal ministries, regional bureaus, Federal and regional research institutes, and from Wondo Genet College of Forestry and Natural Resources and other universities. The senior experts were organised into five teams, which set out to identify effective forest management practices, and enabling conditions for scaling them up, with the aim of significantly enhancing the role of forests in building a climate resilient green economy in Ethiopia. The five forest management practices studied were: the establishment and management of area exclosures; the management of plantation forests; Participatory Forest Management (PFM); agroforestry (AF); and the management of dry forests and woodlands. Each team focused on only one of the five forest management practices, and concentrated its study in one regional state. -

Ethiopia: Amhara Region Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Amhara region administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abrha jara ! Tselemt !Adi Arikay Town ! Addi Arekay ! Zarima Town !Kerakr ! ! T!IGRAY Tsegede ! ! Mirab Armacho Beyeda ! Debark ! Debarq Town ! Dil Yibza Town ! ! Weken Town Abergele Tach Armacho ! Sanja Town Mekane Berhan Town ! Dabat DabatTown ! Metema Town ! Janamora ! Masero Denb Town ! Sahla ! Kokit Town Gedebge Town SUDAN ! ! Wegera ! Genda Wuha Town Ziquala ! Amba Giorges Town Tsitsika Town ! ! ! ! Metema Lay ArmachoTikil Dingay Town ! Wag Himra North Gonder ! Sekota Sekota ! Shinfa Tomn Negade Bahr ! ! Gondar Chilga Aukel Ketema ! ! Ayimba Town East Belesa Seraba ! Hamusit ! ! West Belesa ! ! ARIBAYA TOWN Gonder Zuria ! Koladiba Town AMED WERK TOWN ! Dehana ! Dagoma ! Dembia Maksegnit ! Gwehala ! ! Chuahit Town ! ! ! Salya Town Gaz Gibla ! Infranz Gorgora Town ! ! Quara Gelegu Town Takusa Dalga Town ! ! Ebenat Kobo Town Adis Zemen Town Bugna ! ! ! Ambo Meda TownEbinat ! ! Yafiga Town Kobo ! Gidan Libo Kemkem ! Esey Debr Lake Tana Lalibela Town Gomenge ! Lasta ! Muja Town Robit ! ! ! Dengel Ber Gobye Town Shahura ! ! ! Wereta Town Kulmesk Town Alfa ! Amedber Town ! ! KUNIZILA TOWN ! Debre Tabor North Wollo ! Hara Town Fogera Lay Gayint Weldiya ! Farta ! Gasay! Town Meket ! Hamusit Ketrma ! ! Filahit Town Guba Lafto ! AFAR South Gonder Sal!i Town Nefas mewicha Town ! ! Fendiqa Town Zege Town Anibesema Jawi ! ! ! MersaTown Semen Achefer ! Arib Gebeya YISMALA TOWN ! Este Town Arb Gegeya Town Kon Town ! ! ! ! Wegel tena Town Habru ! Fendka Town Dera -

International Journal of Advanced Research in Biological Sciences

Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. (2019). 6(2): 110-117 International Journal of Advanced Research in Biological Sciences ISSN: 2348-8069 www.ijarbs.com DOI: 10.22192/ijarbs Coden: IJARQG(USA) Volume 6, Issue 2 - 2019 Research Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22192/ijarbs.2019.06.02.013 A Cross Sectional Study on the Prevalence and Possible Risk Factors of Bovine Schistosomiasis in and Around Gozamen District, Northwest Ethiopia Yezina Mengist1 and Nigussie Yilak2* 1 Gozamen Agricultural Office , East Gojjam, ETHIOPIA 2Shewa Robit Municipal Abattoir, Shewa Robit, ETHIOPIA *Corresponding author: Nigussie Yilak; email: [email protected] Abstract A cross sectional study was conducted from April, 2017 to July 2017 in and around Gozamen district to estimate the prevalence and possible risk factors of bovine Schistosomiasis. Simple random sampling was used to select the study animals and sedimentation technique. Out of 384 faecal samples examined 101(26.3%) were found positive for bovine Schistosomiasis. The prevalence of bovine Schistosomiasis was higher in local breed cattle (29.3%) than cross breed cattle (16.1%). Similarly, the prevalence of the disease in male and female cattle was 26.2% and 26.4%, respectively. Cattle having less than 2 years, 2-5years and greater than 5 years old had (18.8%), (28.7%) and (26.0%) disease prevalence, respectively without significant statistical difference (p>0.05). The highest prevalence of Schistosoma infection was observed in poor body conditioned animals (35.5%) followed by medium body conditioned animals (21.1%). Whereas, the lowest prevalence of the disease was observed in good body conditioned animals (11.4%). -

Research Article

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 11, Issue, 08, pp.5884-5890, August, 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24941/ijcr.35811.08.2019 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE MARKET CHAIN ANALYSIS OF BEE HONEY: THE CASE OF AWABEL WOREDA IN EAST GOJJAM ZONE, AMHARA NATIONAL REGIONAL STATE, ETHIOPIA 1Bekalu wube and 2, *Workalemahu Tasew 1Alage Agricultural, Technique and Vocational Education and Training College, Alage, Ethiopia 2Agribusiness and Value Chain Management Program, Hawassa University, PO box 05, Hawassa, Ethiopia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: The study was conducted at Awabel Woreda to analyze the market chain performance of bee honey. Received 10th May, 2019 The area is known for its production of honey. However, market chain of honey is not well Received in revised form understood. The study has focused on market participants, the structure, conduct and performance of 24th June, 2019 honey markets. The research design used for this study was cross sectional survey type. The data were Accepted 12th July, 2019 generated by structured questionnaire, focus group discussions, and key informant interviews. This Published online 31st August, 2019 was supported by secondary data collected from NGO’S, bureau of agriculture and rural development, woreda trade and industry office, CSA, websites, articles, research works and review of Key Words: related literatures. Producers, Collectors, Retailers, Processors and consumers were the main actors in Market chain, honey market chain. Quantity of honey passed through different marketing actors from farmers to Honey, consumers. The Producers- Consumers channel carried the largest volume, which is 38.1% of the Multiple linear regression. -

![Seed System of Tef [Eragrostis Tef (Zucc.) Trotter] in East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia By](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0590/seed-system-of-tef-eragrostis-tef-zucc-trotter-in-east-gojjam-zone-ethiopia-by-1000590.webp)

Seed System of Tef [Eragrostis Tef (Zucc.) Trotter] in East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia By

Seed system of tef [Eragrostis tef (Zucc.) Trotter] In East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia By Melkam Anteneh, Dr. Firew Mekbib Plant Science department, Haramaya University, P.O.Box-138, Dire Dawa-Ethiopia. E-mail: [email protected]. Or [email protected] Tel: +251 255 530 313. This research was initiated to document Seed System on tef [Eragrostis tef (Zucc.)Trotter]; specifically, quantify the relative importance of formal and farmer tef seed system. A total of 100 sample households drawn from four PAs of the two districts were interviewed using structured interview schedule. Qualitative data were also collected using group discussion among selected tef growers and extension development agents who were working in the respective PAs. The use of appropriate technologies like fertilizer, improved seed, weeding and/or herbicide application with the recommended rate and time helped to increase productivity. Dissemination of improved varieties to farmers is limited. The informal seed system should prioritize improving seed quality by increasing awareness and skills of farmers, improving seed quality of early generations and market access. In conclusion, to enhance tef productivity in east Gojjam zone through supply of improved varieties and quality seed it is important to integrate formal and farmer (informal) seed system. Key words: Farmer and formal seed system 1 | Page Vol 1, No 3 / 2 0 1 3 ABC Research Alert INTRODUCTION Ethiopian farmers grow tef for a number of merits, which is mainly attributed to the socioeconomic, cultural and agronomic benefits. The area under tef cultivation is over 2,481,333 hectares (ha) of land with annual production of 3,028,018.1ton (t) and yield of 12.2 tons per hectare (t/ha).