Tokugawa Japan (1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Otorisama Continues to Be Loved by the People

2020 edition Edo to the Present The Sugamo Otori Shrine, located near the Nakasendo, has been providing a spiritual Ⅰ Otorisama continues to be loved sanctuary to the people as Oinarisama (Inari god) and continues to be worshipped and by the people loved to this today. Torinoichi, the legacy of flourishing Edo Stylish manners of Torinoichi The Torinoichi is famous for its Kaiun Kumade Mamori (rake-shaped amulet for Every November on the day of the good luck). This very popular good luck charm symbolizes prosperous business cock, the Torinoichi (Cock Fairs) are and is believed to rake in better luck with money. You may hear bells ringing from all held in Otori Shrines across the nation parts of the precinct. This signifies that the bid for the rake has settled. The prices and many worshippers gather at the of the rakes are not fixed so they need to be negotiated. The customer will give the Sugamo Otori Shrine. Kumade vendor a portion of the money saved from negotiation as gratuity so both The Sugamo Otori Shrine first held parties can pray for successful business. It is evident through their stylish way of business that the people of Edo lived in a society rich in spirit. its Torinoichi in 1864. Sugamo’s Torinoichi immediately gained good reputation in Edo and flourished year Kosodateinari / Sugamo Otori Shrine ( 4-25 Sengoku, Bunkyo Ward ) MAP 1 after year. Sugamo Otori Shrine was established in 1688 by a Sugamo resident, Shin However, in 1868, the new Meiji Usaemon, when he built it as Sugamoinari Shrine. -

1 Chapter 1 the Legal System and the Economic, Political and Social

Chapter 1 The Legal System and the Economic, Political and Social Development in Japan I Introduction In this course we will follow briefly the history of legal development in Japan and ask how legal reforms have influenced, and have been influenced by, economic development, which has also influenced, and has been influenced by, political and social development in Japan. It is a part of the complexity of mutual relations between legal, economic, political, and social development in a society, from which we will clarify the roles of legal reform for the development of the country. The way to development is not simple and single, but there are various routes to approach development. The well-known route which had occurred in the U.K. was that the Parliament finally succeeded in limiting the political power of the King by the Glorious Revolution in 1688, having the Bill of Rights to be guaranteed, and establishing the rule of law, which led to the industrial revolution since the 17th century. It was a typical pattern of mutual relation between political development (the popular revolution), legal development (the rule of law), and economic development (the industrial revolution). Then how was it in Japan? Acemoglu and Robinson analyzed the Japanese pattern as follows: By 1890 Japan was the first Asian country to adopt a written constitution, and it created a constitutional monarchy with an elected parliament, the Diet, and an independent judiciary. These changes were decisive factors in enabling Japan to be the primary beneficiary from the Industrial Revolution in Asia.1 According to Acemoglu and Robinson, the Japanese way seems to be similar to that of the U.K., for the political development (the Diet in constitutional monarchy), which was sustained by the legal development (the written constitution), led to the industrial revolution. -

EARLY MODERN JAPAN 2008 Samurai and the World of Goods

EARLY MODERN JAPAN 2008 Samurai and the World of Goods: vast majority, who were based in urban centers, could ill afford to be indifferent to money and the Diaries of the Toyama Family commerce. Largely divorced from the land and of Hachinohe incumbent upon the lord for their livelihood, usually disbursed in the form of stipends, samu- © Constantine N. Vaporis, University of rai were, willy-nilly, drawn into the commercial Maryland, Baltimore County economy. While the playful (gesaku) literature of the late Tokugawa period tended to portray them as unrefined “country samurai” (inaka samurai, Introduction i.e. samurai from the provincial castle towns) a Samurai are often depicted in popular repre- reading of personal diaries kept by samurai re- sentations as indifferent to—if not disdainful veals that, far from exhibiting a lack of concern of—monetary affairs, leading a life devoted to for monetary affairs, they were keenly price con- the study of the twin ways of scholastic, meaning scious, having no real alternative but to learn the largely Confucian, learning and martial arts. Fu- art of thrift. This was true of Edo-based samurai kuzawa Yukichi, reminiscing about his younger as well, despite the fact that unlike their cohorts days, would have us believe that they “were in the domain they were largely spared the ashamed of being seen handling money.” He forced paybacks, infamously dubbed “loans to maintained that “it was customary for samurai to the lord” (onkariage), that most domain govern- wrap their faces with hand-towels and go out ments resorted to by the beginning of the eight- after dark whenever they had an errand to do” in eenth century.3 order to avoid being seen engaging in commerce. -

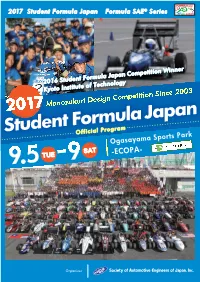

Student Formula Japan Formula SAE® Series C Ompetition Site 至 東名掛川 シャトルバス運行区間 Shuttle Bus to Tomei EXPWY Kakegawa I.C

7 1 0 2 2017 Student Formula Japan Formula SAE® Series C ompetition Site 至 東名掛川 シャトルバス運行区間 Shuttle Bus To Tomei EXPWY Kakegawa I.C. EV充電 指定車両以外 P4 ~ エコパアリーナ ~ P11 ~ エコパアリーナ ~ P4 EV Charge 動的エリア 車両通行止 Parking4 ~ Ecopa Arena ~ Parking11 ~ Ecopa Arena ~Parking4 シ ャト ル バ ス Road Blocked バス停 Except 至 国道1号 Bus Stop Appointment Car To Route1 グ ラ ウ ンド1 トイレ Toilet グ ラ ウ ンド 2 至JR愛野駅 救護所 First Aid P11(Parking11) チーム待機エリア To JR Aino Road Blocked Approved Tearm Station シ ャト ル バ ス Shuttle Bus Waiting Area Road Blocked 芝生 Competition Winner 階段 Stairs 観覧エリア 広場3 Spectator Viewing Area 2016 Student Formula Japan 指定車両以外 遊歩道 車両通行止 Pedestrian Way Road Blocked プラクティストラック Practice Tracks Kyoto Institute of Technology Except Appointment Car 給油 動的イベント Fuel Station Dynamic Events 17 Monozukuri Design Competition Since 2003 関係者以外立入禁止エリア 20 スタッフ関係者駐車場 アクセラレーション Acceleration Off Limits Area Staff Parking ス キ ッド パ ッド Skid-pad Japan オ ート ク ロ ス Autocross エンデュランス Endurance Enlargement Formula 至 東名掛川 Student Official Program To Tomei EXPWY COPA Guide Map Kakegawa I.C. 掛川ゲート Ogasayama Sports Park E Kakegawa Gate 至 国道1号 指定車両以外 グ ラ ウ ンド1 To Route1 車両通行止 SAT グ ラ ウ ンド2 Road Blocked -ECOPA- Except TUE Appointment Car - デザインファイナル、 9 交流会、表彰式 シ ャト ル バ ス バス停 芝生 グ ラ ウ ンド 5 Bus Stop . Design Final, Networking event, 広場3 3 9 Awards Ceremony 指定車両以外 車両通行止 動的イベント Road Blocked Dynamic Events Except Appointment Car エコパ出入口 スタッフ関係者駐車場 ECOPA Entrance Staff Parking 至JR愛野駅 袋井ゲート To JR Aino Station Fukuroi Gate 歩行者 ゲ ート By Car エコパ アリーナ シ ャト ル バ ス バス停 大 阪 名古屋 袋井 I.C. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02903-3 - The Cambridge History of Japanese Literature Edited by Haruo Shirane and Tomi Suzuki Index More information Index Abbot Rikunyo (1734–1801), 465 Ukiyo monogatari (Tales of the Floating Abe Akira (1934–89), 736 World, 1661), 392 Abe Kazushige (b. 1968), 765, 767 Atsumori, 8, 336, 343 Abe Ko¯bo¯(1924–93), 701, 708, 709, 760 aware (pathos), 80, 138, 239, 299, 474, 486 Adachigahara, 339 Ayukawa Nobuo (1920–86), 717 akahon (red books), 510–22 Azuma nikki (Eastern Diary, 1681), 409 Akazome Emon, 135, 161, 170, 193–7 Azumakagami, 201 Akimoto Matsuyo (1911–2001), 708 azuma-uta (eastland songs), 77, 79, 82, 111 Akizato Rito¯(?–1830), 524 To¯kaido¯ meisho zue (Illustrated Sights of Backpack Notes. See Matsuo Basho¯ the To¯kaido¯, 1797), 524–5 Bai Juyi (or Bo Juyi, J. Haku Kyoi or Haku Akutagawa Ryu¯nosuke (1892–1927), 286, 630, Rakuten, 772–846), 124 639, 669, 684, 694–5, 700 Baishi wenji (Collected Works of Bai Juyi, ancient songs, 25, 26, 28–9, 37, 40–4, 52, 57–8, J. Hakushi monju¯ or Hakushi bunshu¯, 60; see also kiki kayo¯ 839), 184–6, 283 Ando¯ Tameakira (1659–1716), 138, 480 Changhen-ge (Song of Never-Ending Shika shichiron (Seven Essays of Sorrow, J. Cho¯gonka, 806), 152 Murasaki, 1703), 138 Baitei Kinga (1821–93), 530 anime, 729, 764 bakufu (military government), 95, 201, 211–12, Anzai Fuyue (1898–1965), 684, 714–15 215, 216, 295, 297, 309, 312, 314, 348–9, aohon (green books), 510–22 374–6, 377–8, 388, 389, 393–5, 419, 432–3, Aono Suekichi (1890–1961), 658–9 505–7, 520–2, 532–3 Arai Hakuseki (1657–1725), 4, 461, 546 banka (elegy), 54, 63–4, 76, 77, 83 Arakida Moritake (1473–1549), 326 banzuke (theater programs), 391, 425, 452 Arakida Reijo (1732–1806), 377 Battles of Coxinga. -

HIRATA KOKUGAKU and the TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon

SPIRITS AND IDENTITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NORTHEASTERN JAPAN: HIRATA KOKUGAKU AND THE TSUGARU DISCIPLES by Gideon Fujiwara A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Gideon Fujiwara, 2013 ABSTRACT While previous research on kokugaku , or nativism, has explained how intellectuals imagined the singular community of Japan, this study sheds light on how posthumous disciples of Hirata Atsutane based in Tsugaru juxtaposed two “countries”—their native Tsugaru and Imperial Japan—as they transitioned from early modern to modern society in the nineteenth century. This new perspective recognizes the multiplicity of community in “Japan,” which encompasses the domain, multiple levels of statehood, and “nation,” as uncovered in recent scholarship. My analysis accentuates the shared concerns of Atsutane and the Tsugaru nativists toward spirits and the spiritual realm, ethnographic studies of commoners, identification with the north, and religious thought and worship. I chronicle the formation of this scholarly community through their correspondence with the head academy in Edo (later Tokyo), and identify their autonomous character. Hirao Rosen conducted ethnography of Tsugaru and the “world” through visiting the northern island of Ezo in 1855, and observing Americans, Europeans, and Qing Chinese stationed there. I show how Rosen engaged in self-orientation and utilized Hirata nativist theory to locate Tsugaru within the spiritual landscape of Imperial Japan. Through poetry and prose, leader Tsuruya Ariyo identified Mount Iwaki as a sacred pillar of Tsugaru, and insisted one could experience “enjoyment” from this life and beyond death in the realm of spirits. -

Boku in Edo Epistolary Texts

Boku in Edo Epistolary Texts KATSUE AKIBA REYNOLDS The change from the feudal period to the modern via the Meiji Restoration was certainly one of the most turbulent and complex in the history of Japan and many details of the change remain unexplained. In the process of such a fundamental social change, language inevitably plays a crucial role in forming and accommodating new meanings and new ideologies. This essay is about boku, a first person pronoun or self-reference form for males. It ar.peared rather abruptly in Japanese around the time of the MeiJi Restoration and it lias quickly become one of the major male first person pronouns. Although it is apparently of a Chinese origin, its history as a Japanese word is not necessarily clear. How and why did it come into being in Japanese at the time when it did? I have examined some texts from the Edo period in an attempt to bring to light the early history of boku in Japanese. Bringing various linguistic, sociological and historical facts together, it becomes possible to see the way boku entered Japanese. Spread of the use of boku began in personal letters exchanged among a close circle of samurai scholars-forerunners of modern intellectuals. Self in Feudal Society That Japanese has several variants of self-reference is well known. Where an English speaker uses 'I' regardless of his/her social status, class, age, gender, etc., for example, a Japanese speaker would have to choose an appropriate form from a set of first person pronouns including watakushi, watashi, boku, and ore. -

Nihonbashi: Edo's Contested Center Marcia Yonemoto

, East Asian History NUMBERS 17/18· JUNE/DECEMBER 1999 Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University 1 Editor Geremie R. Barme Assistant Editor Helen Lo Editorial Board Mark Elvin (Convenor) John Clark Andrew Fraser Helen Hardacre Colin Jeffcott W. ]. F. Jenner Lo Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Design and Production Helen Lo Business Manager Marion Weeks Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This double issue of East Asian History, 17/18, was printed in FebrualY 2000. Contributions to The Editor, East Asian History Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 26249 3140 Fax +61 26249 5525 email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to Subscriptions, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Whose Strange Stories? P'u Sung-ling (1640-1715), Herbert Giles (1845- 1935), and the Liao-chai chih-yi John Minford and To ng Man 49 Nihonbashi: Edo's Contested Center Marcia Yonemoto 71 Was Toregene Qatun Ogodei's "Sixth Empress"? 1. de Rachewiltz 77 Photography and Portraiture in Nineteenth-Century China Regine Thiriez 103 Sapajou Richard Rigby 131 Overcoming Risk: a Chinese Mining Company during the Nanjing Decade Ti m Wright 169 Garden and Museum: Shadows of Memory at Peking University Vera Schwarcz iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing M.c�J�n, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Talisman-"Passport for wandering souls on the way to Hades," from Henri Dore, Researches into Chinese superstitions (Shanghai: T'usewei Printing Press, 1914-38) NIHONBASHI: EDO'S CONTESTED CENTER � Marcia Yonemoto As the Tokugawa 11&)II regime consolidated its military and political conquest Izushi [Pictorial sources from the Edo period] of Japan around the turn of the seventeenth century, it began the enormous (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1975), vol.4; project of remaking Edo rI p as its capital city. -

HST Catalogue

LIST 195 – 1 – JAPANESE INTEREST H ANSHAN TANG BOOKS LTD Unit 3, Ashburton Centre 276 Cortis Road London SW15 3AY UK Tel (020) 8788 4464 Fax (020) 8780 1565 Int’l (+44 20) [email protected] www.hanshan.com 14 East Fresian Tea Museum: MELK EN BLOED. Exquisite Porcelain from the Middle Kingdom. Norden, 2018. 124 pp. Colour plates throughout. 21x21 cm. Paper. £25.00 Catalogue of an exhibition at the East Fresian Tea Museum in Norden, Germany. The first dedicated exhibition on Chinese export porce- lain decorated in red and gold and dating mostly from the Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong reigns of the Qing dynasty. Accompanied by a number of other exhibits including some similar Japanese examples. Illustrated throughout. English edition. 55 Barry Davies Oriental Art: JAPANESE METALWORK OF THE MEIJI PERIOD (1868-1912). London, 1989. 54 pp. 38 colour plates, 19 illustrations. 30x21 cm. Paper. £30.00 The catalogue of an exhibition of 42 pieces. 58 Berger, Karl: HUGO HALBERSTADTS SAMLING AF JAPANSKE SVAERDPRYDELSER. Skaenket Det Danske Kunstindustrimuseum. Copenhagen, 1953. 61 pp. 12 plates, illustrating 50 tsuba and other sword furnishings. 25x16 cm. Paper. £45.00 Catalogue of the Halberstadt collection of tsuba and other sword furnishings. The collection was given to the Danish Industrial Art Museum. Text in Danish. Scarce. 59 Bottomley, Ian: JAPANESE ARMOR: THE GALENO COLLECTION. San Rafael, 1997. 202 pp. 113 colour plates, text drawings. Cloth. £50.00 The Galeno Collection of Japanese armour here presents more than 100 pieces of armour, helmets, masks etc. ranging in date from the 14th to the 19th centuries. -

Entwicklung Und Struktur Des Japanischen Managementsystems

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Götz, Klaus (Ed.); Iwai, Kiyoharu (Ed.) Book Entwicklung und Struktur des japanischen Managementsystems Managementkonzepte, No. 15 Provided in Cooperation with: Rainer Hampp Verlag Suggested Citation: Götz, Klaus (Ed.); Iwai, Kiyoharu (Ed.) (2000) : Entwicklung und Struktur des japanischen Managementsystems, Managementkonzepte, No. 15, ISBN 3-87988-499-4, Rainer Hampp Verlag, München und Mering This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/117367 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten -

Meisho Zue and the Mapping of Prosperity in Late Tokugawa Japan

Meisho Zue and the Mapping of Prosperity in Late Tokugawa Japan Robert Goree, Wellesley College Abstract The cartographic history of Japan is remarkable for the sophistication, variety, and ingenuity of its maps. It is also remarkable for its many modes of spatial representation, which might not immediately seem cartographic but could very well be thought of as such. To understand the alterity of these cartographic modes and write Japanese map history for what it is, rather than what it is not, scholars need to be equipped with capacious definitions of maps not limited by modern Eurocentric expectations. This article explores such classificatory flexibility through an analysis of the mapping function of meisho zue, popular multivolume geographic encyclopedias published in Japan during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The article’s central contention is that the illustrations in meisho zue function as pictorial maps, both as individual compositions and in the aggregate. The main example offered is Miyako meisho zue (1780), which is shown to function like a map on account of its instrumental pictorial representation of landscape, virtual wayfinding capacity, spatial layout as a book, and biased selection of sites that contribute to a vision of prosperity. This last claim about site selection exposes the depiction of meisho as a means by which the editors of meisho zue recorded a version of cultural geography that normalized this vision of prosperity. Keywords: Japan, cartography, Akisato Ritō, meisho zue, illustrated book, map, prosperity Entertaining exhibitions arrayed on the dry bed of the Kamo River distracted throngs of people seeking relief from the summer heat in Tokugawa-era Kyoto.1 By the time Osaka-based ukiyo-e artist Takehara Shunchōsai (fl. -

The Making of Modern Japan

The Making of Modern Japan The MAKING of MODERN JAPAN Marius B. Jansen the belknap press of harvard university press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright © 2000 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Third printing, 2002 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2002 Book design by Marianne Perlak Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jansen, Marius B. The making of modern Japan / Marius B. Jansen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-674-00334-9 (cloth) isbn 0-674-00991-6 (pbk.) 1. Japan—History—Tokugawa period, 1600–1868. 2. Japan—History—Meiji period, 1868– I. Title. ds871.j35 2000 952′.025—dc21 00-041352 CONTENTS Preface xiii Acknowledgments xvii Note on Names and Romanization xviii 1. SEKIGAHARA 1 1. The Sengoku Background 2 2. The New Sengoku Daimyo 8 3. The Unifiers: Oda Nobunaga 11 4. Toyotomi Hideyoshi 17 5. Azuchi-Momoyama Culture 24 6. The Spoils of Sekigahara: Tokugawa Ieyasu 29 2. THE TOKUGAWA STATE 32 1. Taking Control 33 2. Ranking the Daimyo 37 3. The Structure of the Tokugawa Bakufu 43 4. The Domains (han) 49 5. Center and Periphery: Bakufu-Han Relations 54 6. The Tokugawa “State” 60 3. FOREIGN RELATIONS 63 1. The Setting 64 2. Relations with Korea 68 3. The Countries of the West 72 4. To the Seclusion Decrees 75 5. The Dutch at Nagasaki 80 6. Relations with China 85 7. The Question of the “Closed Country” 91 vi Contents 4. STATUS GROUPS 96 1. The Imperial Court 97 2.