Chapter Six Nepali Migration and Settlement Into Northeast India In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meghalaya Receives Agriculture Award Meghalaya Receives

March, 2018 MEGNEWS MEGNEWSMONTHTLY NEWS BULLETIN A PUBLICATION OF THE DIRECTORATE OF INFORMATION & PUBLIC RELATIONS, MEGHALAYA TOLL - FREE DATE: March 29, 2018 FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION ISSUE NO. 104 NO. - 1800-345-3644 CM attends Natural CM attends International CM urges Youth to Workshop on Continuing Two-Day Mega Health Swearing - in Ceremony On the Lighter Side Resource Management Inter-Disciplinary Seminar look for opportunities Professional Development Mela Concludes of New CM and Cabinet and Climate Change Meet beyond State at Regional of Counsellors Ministers at Tura 2 3 Colloquium 4 5 6 7 8 Meghalaya Receives Agriculture award Prime Minister, Shri. Narendra Modi on 17th March 2018 awarded Meghalaya an award, which was possible because of the hard work of the farmers and the for its growth in the agriculture sector. Chief Minister of Meghalaya, Shri. officials of the Department of Agriculture and other stakeholders. Shri. Modi Conrad K. Sangma received the award on behalf of the people of the State in handed over the award to the Chief Minister during the Krishi Unnati Mela presence of Agriculture Minister, Shri. Banteidor Lyngdoh. held at India Agriculture Research Institute Mela Groud at Pusa in New Delhi. Addressing the gathering, the Prime Minister said that such Unnati Melas The Chief Minister has dedicated the award to the people of the State especially play a key role in paving the way for New India. He said that today, he has farmers. “It gives an immense pleasure that I have received the award on behalf the opportunity to simultaneously speak to two sentinels of New India – of the farmers of the State, who have scripted a success story. -

Urban Development

MMEGHALAYAEGHALAYA SSTATETATE DEVELOPMENTDEVELOPMENT RREPORTEPORT CHAPTER VIII URBAN DEVELOPMENT 8.1. Introducti on Urbanizati on in Meghalaya has maintained a steady growth. As per 2001 Census, the state has only 19.58% urban populati on, which is much lower than the nati onal average of 28%. Majority of people of the State conti nue to live in the rural areas and the same has also been highlighted in the previous chapter. As the urban scenario is a refl ecti on of the level of industrializati on, commercializati on, increase in producti vity, employment generati on, other infrastructure development of any state, this clearly refl ects that the economic development in the state as a whole has been rather poor. Though urbanizati on poses many challenges to the city dwellers and administrators, there is no denying the fact that the process of urbanizati on not only brings economic prosperity but also sets the way for a bett er quality of life. Urban areas are the nerve centres of growth and development and are important to their regions in more than one way. The current secti on presents an overview of the urban scenario of the state. 88.2..2. UUrbanrban sseett llementement andand iitsts ggrowthrowth iinn tthehe sstatetate Presently the State has 16 (sixteen) urban centres, predominant being the Shillong Urban Agglomerati on (UA). The Shillong Urban Agglomerati on comprises of 7(seven) towns viz. Shillong Municipality, Shillong Cantonment and fi ve census towns of Mawlai, Nongthymmai, Pynthorumkhrah, Madanrti ng and Nongmynsong with the administrati on vested in a Municipal Board and a Cantonment Board in case of Shillong municipal and Shillong cantonment areas and Town Dorbars or local traditi onal Dorbars in case of the other towns of the agglomerati on. -

Nerccdiptr- 02Shgswm-08-Section-8

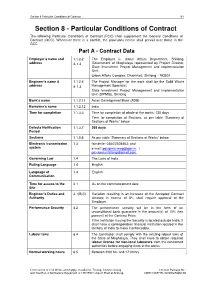

Section 8 Particular Conditions of Contract 8-1 Section 8 - Particular Conditions of Contract The following Particular Conditions of Contract (PCC) shall supplement the General Conditions of Contract (GCC). Whenever there is a conflict, the provisions herein shall prevail over those in the GCC. Part A - Contract Data Employer’s name and 1.1.2.2 The Employer is: Urban Affairs Department, Shillong, address & 1.3 Government of Meghalaya represented by Project Director, State Investment Project Management and Implementation Unit, Urban Affairs Complex, Dhankheti, Shillong - 793001 Engineer’s name & 1.1.2.4 The Project Manager for the work shall be the Solid Waste address & 1.3 Management Specialist State Investment Project Management and Implementation Unit (SIPMIU), Shillong Bank’s name 1.1.2.11 Asian Development Bank (ADB) Borrower’s name 1.1.2.12 India Time for completion 1.1.3.3 Time for completion of whole of the works: 730 days Time for completion of Sections: as per table “Summary of Sections of Works” below Defects Notification 1.1.3.7 365 days Period Sections 1.1.5.6 As per table “Summary of Sections of Works” below Electronic transmission 1.3 facsimile: 0364/2505463; and system e-mail: [email protected]. / [email protected]. Governing Law 1.4 The Laws of India Ruling Language 1.4 English Language of 1.4 English Communication Time for access to the 2.1 As on the commencement date. Site Engineer’s Duties and 3.1(B)(ii) Variation resulting in an increase of the Accepted Contract Authority Amount in excess of 5% shall require approval of the Employer. -

ORDER 1. Entry of Tourists from Outside the State Shall Not Be

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA HOME (POLITICAL) DEPARTMENT No. POL.75/2020/Pti/100 Dated, Shillong the 28" May, 2021 ORDER Whereas, it is observed that the number of COVID-19 cases in the State continues to rise sharply and hospital bed occupancy is nearing saturation; Therefore, in supersession to all orders issued in respect of Containment Measures in the State, the following shall be enforced in the State w.e.f. 318t May, 2021 until further orders. Entire State: 1. Political, public, social and religious gatherings are not permitted including conferences, meetings and trainings Entry of tourists from outside the State shall not be permitted and all tourist spots shall remain closed. Sports activities are not permitted. Inter-State movement of persons shall be restricted. This shall not apply for transit vehicles of Assam / Tripura / Manipur / Mizoram. 5. International Border Trade shall be regulated by the Deputy Commissioners. East Khasi Hills District: 6. Lockdown shall be extended in East Khasi Hills District till 5:00 AM of 7'" June, 2021. 7. The Deputy Commissioner, East Khasi Hills District shall make suitable arrangements for availability of essential commodities in the localities on need basis. 8. Home Delivery Services are permitted subject to prior permission and regulation by the Deputy Commissioner, East Khasi Hills District. 9. Inter-district movement of persons from and to East Khasi Hills District shall be restricted. 10. All Central Government offices other than those notified by Home (Political) Department vide Notification No. POL.117/2020/Pt.1I/136, dated 28-05-2021 shall remain closed. 11. All State Government offices other than those notified by Personnel & A.R (A) Department vide Notification No. -

The Khasi States and Shillong Municipality

THE KHASI STATES AND SHILLONG MUNICIPALITY: On the day, the Constitution of India came into force; Khasi States became a part of the State of Assam. Prior to this, there were some agreements relating to accession of the Khasi States with the Indian Union to which reference shall be made later. Before this is done, a bird's eye view at the history of these States may not be out of place. Khasis, perhaps, represent one of the earliest waves of migration to India's northeast corner. Historians are not being able to say with authority how early and from where the migration took place. Some trace it even to the days of Mahabharata; but authenticate account is lacking and it is because of this that Major P.R.Giirdon' has regarded the question relating to the origin of the Khasis as a 'very vexed' one. After referring to various opinions about the place from where the Khasis are said to have migrated, Major Gurdon was of the view that the Khasis are an offshoot of the Mon people and must have moved into Assam from east, meaning Burma, and not from west or north. The documented history of the Khasis till the advent of the British consists almost entirely of references to Khasi kings and kingdoms in the 'Buranjis' of Ahom Kings, annals of Koch King Naranarayana and some reference in the chronicles of the Kings of Tippera. The earliest named dynasty is perhaps that of Malyngiang Syiems, who were regarded as supernatural beings and Godkinds. Some historians would place these kings around 1200 A.D., while others would not agree with this. -

Part IA, Series-16, Meghalaya

For Official Use CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES 16 MEGHALAYA PART I-A ADMINISTRATION REPORT (ENUMERATION) TAPAN SENAPATI Director of Census Operations, Meghalaya CONTENTS Page PREFACE (v) Chapter Introduction 1 Chapter II Preparatory Steps 2 Chapter III Preparation for the Census 6 Chapter IV Building up of the Organisation 17 Chapter '. V Touring and Training Programmes 19 Chapter VI Census Schedules and Instruction-Translation, Printing and Distribution 21 Chapter VII Procurement of Maps 22 Chapter VIlI Preparation of Rural and Urban Frame 44 Chapter IX Enumeration Agency 28 Chapter X Houselisting Operations 30 Chapter XI Enumeration 33 Chapter XII Directives issued by the Central/State Govemments 38 Chapter XIII General 39 Chapter XIV Post-Enumeration Check 43 Chapter XV Condusion and Acknowledgement 44 APPENDICES Appendix - Otculars issued by the Registrar General, India 45 Appendix - II Circulars issued by the Director of Census Operations, Meghalaya 83 Appendix - III Important letters from the State Government of Megtlalaya 172 Appendix - IV Census Schedules - 1991 Census 186 (iii) PREfACE It has been a tradition that 'after each decennial census of the population an .. Administration Report - E.numeration" is written by each and every Director of Census Operations who has conducted the Census to record therein his functions, duties and experiences in the course of the census operations in order to act as a guide to his suc«~ssor in the next decennial census. With the passage of time and due to the continuous rise in the population. the number of districts. Dev. Blocks, drdes, etc., ha~ risen by many folds. This increase has made the conduct of the census operations more complicated and strenuous demanding huge manpower at every level. -

Shillong Solid Waste Management Subproject Components

Initial Environmental Examination (Updated) February 2015 IND: North-Eastern Region Capital Cities Development Investment Program (Tranche 2) – Shillong, Meghalaya Subproject Prepared by the State Investment Program Management and Implementation Unit (SIPMIU), Urban Development Department for the Asian Development Bank. This is an updated version of the revised IEE posted in January 2013 available on http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/ project-document/77248/35290-033-ind-iee-11.pdf CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 29 June 2011) Currency unit ± rupee (INR) INR1.00 = $0.0222 $1.00 = INR 45.040 ABBREVIATIONS ADB ² Asian Development Bank CBO ² Community Building Organization CLC ² City Level Committees CPHEEO ² Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organization CTE ² Consent to Establish CTO ² Consent to Operate DSMC ² Design Supervision Management Consultant EAC ² Expert Appraisal Committee EIA ² Environmental Impact Assessment EMP ² Environmental Management Plan GSPA ² Greater Shillong Planning Area GRC ² Grievance Redress Committee H&S ² Health and Safety IEE ² Initial Environmental Examination IPCC ² Investment Program Coordination Cell lpcd ² liters per capita per day MFF ² Multitranche Financing Facility MOEF ² Ministry of Environment and Forests MSW ² Municipal Solid Waste NAAQS ² National Ambient Air Quality Standards NEA ² National-Level Executing Agency NER ² North Eastern Region NERCCDIP ² North Eastern Region Capital Cities Development Investment Program NGO ² Nongovernmental Organization NSC ² National Level Steering -

District Census Handbook, East Khasi Hills, Part XIII a & B, Series-14

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES 1'4. MEGHALAYA PARTS XIII A & B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT EAST KHASI HILLS DISTRICT J. TAYENG OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE. Director of Cenius Operations MEGHALAYA CONTENTS Pa~. FOREWORD I-II PREFACE I-IV MAPS ... Important Statistics Census Concepts ... I-!' History of the District and the District Census Handbooks 1-7 Major Social and Cultural Events of East Khasi Hiils Distr~ct ,-j Brief Description of Places of Religious, Historical Or Archaeological Importance 1. Places of Tourist ~nterest ••. 11-12 ~p.aly.sis of Tables 13 Fly leaf to Table-l 15 Table-l Population, Number of villages and Towns, 198.1, 16 .Fly leaf to Table-2 17 Table-2 Decadal change in distribution of Population "' .. 18 ;'able-3 Dis1ribution of Villages by Popul~tjon It Table-4 Distribution of villages by density 20 Table-5 Proportion of Scheduled Castes Populatibn to total Population in the villages 21 Table-6 Proportion of ~~p.eduled Tribes Population-to total PopUlation in the villages !I .Table-7 Proportion of Scheduled Caste~j'Tribes Population in Towns J \~3 TabJe- 8 Literacy Rates ·by Population'Ranges by villages ~4 'Table-9 Literacy Rate~ for Towns !5 Fly leaf to Table-IO 26 Tabie-IO Percentage of literate workers, non-workers, scheduled castes/tribes PopUla 21-29 tion in the district. Fly leaf to Table-ll ... J Table-ll Distribution of villages according to the_,av<\ilability of different ame?,ities Table -12 Prop'Qrtion of rural Population served by different amenities Table-13 Distribution of villages not having certain amenities, arranged by distance ranges from places wJ:ere tbese are available. -

Service Paper

Gaurav Bhatia et al., International Journal of Research in Engineering, IT and Social Sciences, ISSN 2250-0588, Impact Factor: 6.565, Volume 10 Issue 01, January 2020, Page 1-10 Does the Polluter Pay? Case Study - Shillong: Scotland of the East Col (Dr) Gaurav Bhatia1, Arundhati Bhatia2, Abhimanyu Bhatia3 and Ranju Bhatia4 1(Chitkara Business School, Chitkara University) 2(Student, Five Year Integrated Law Course, Army Institute of Law, Mohali, SAS Nagar, Punjab) 3(Chitkara Business School, Chitkara University) 4(Faculty, Satluj Public School, Panchkula) Abstract: Being a typical tourist destination the Shillong Metropolitan Region includes eleven small towns. Till Jun 2015 the disposal of garbage was being done by residents and commercial establishments in garbage dumps. The Shillong Municipal Board (SMB) instituted a concept of “free doorstep collection of segregated garbage” by mobile vans. The segregation, storage at source and subsequent collection of garbage from the various localities is facilitated by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) MoU funded by the North-Eastern Region Capital Cities Development Investment Program (NERCCDIP); complimented with the “Polluter Pays Principle (PPP)”, wherein both the state government and the local “Dorbar” have ownership of the process. The paper tries to establish the success or otherwise of the implementation of the “Polluter Pays Principle (PPP)” in the Shillong Metropolitan Region to include its contribution towards the “Swachta Abhiyan” and capability to generate a source of reliable funding to keep Shillong clean. Keywords: Swachta Abhiyan; City Preparedness; Polluter Pays Principle; Segregation of garbage; Local Government. (Abstract: Total Words – 148) _________________________________________________________________________________________ I. INTRODUCTION Shillong town, India (25°34'8.11"N, 1°52'59.27"E) was established in the year 1864 by the British Government. -

District Census Handbook, Part XII-A & B, East Khasi Hills, Series-17, Megalaya

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 SERIES-17 MEGHALAYA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Part XII - A & B EAST KHASI HILLS VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY ~ VILLAGE AND TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT N.K. lASKAR Arunachal Pradesh Civil Service Director of Census Operations, Meghalaya INDIA POSITION OF MEGHALA YA IN INDIA 2001 BOUNDARY, INTERNATIONAL -- BOUNDARY, STATEIU.T. ____ CAPITAL OF INDIA * CAPITAL OF STATE I U.T. • KILOMETRES 100 0 100 200 300 400 r._.L:L._ ...l. ..±:=±===I RAJASTHAN BAY o F BIEN G A 'L ANDHRA PRADESH Coco~ • ~ (UV,,""' ... AHl _Nlrcof\dl..,_t ii'iillAj a \l f ,.. .,.. "'-. ~ <;1 . '.: "-I/l i :l' {} ANDAMAN SEA "Kavarattl 0:'" ~~ _0 <) '1" The admlnlstratlve hcadquartelS Chandigarh, ,,0 ;,() cit -GI ../ i. Hal)'anB and Punjab are at Chandigam, f!i "f p. PONDICHERRY '"-<l, N D I A N c A N ~~--=------- (/) z o (/) w >- ~ . <cO II) ~w W Ir a c ...J> t- N ·_ W « ::I :1:1- o ...I a (!)c( S2 ~ .. wO:: :EI- a (/) Z ::E c c( ..J z Male and Female dancers The costumes and jewellery worn by male and female dancers are described below : Female (a) Ka Jingpien Shad: A long piece of cloth which is covered from the waist till the ankle of the foot. (b) Ka Sopti Mukmor : A full-sleeve velvet blouse decorated with a lace at the neck. (c) Ka Dhara Rang Ksiar : This is the top:most cover on the body. Woven in golden thread it consist of two rectangular pieces. One piece cover the body from one side and is pinned on the opposite shoulder. -

A Study on Man Power Requirement in Education at the Primary Level in Meghalaya

A STUDY ON MAN POWER REQUIREMENT IN EDUCATION AT THE PRIMARY LEVEL IN MEGHALAYA INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 Introduction With the ever increasing awareness of people for quality education, there is an even greater awareness of the need for overall qualitative improvement in classroom instruction. Often for want of teachers with the prescribed qualification, schools in rural areas in particular, are left with no choice but to appoint locally available teachers even if such appointees lack the requisite qualification. It is an oft repeated statement that one of the inhibiting factors, which impede the growth of quality education, is the lack of adequate number of qualified teachers for meeting the requirements of schools. This often stems from the fact that vacancies remain unfilled for years together coupled by lack of funds and the unwillingness of most teachers to work in the remote rural areas. This is further compounded by the shortage of trained and competent teachers. There is every possibility that even in a small state like Meghalaya, school authorities are confronted with these similar kinds of problems. Compounding this problem is the unfilled vacancy caused by superannuation or unfilled vacant posts which often lead to undue high drop-out rate of children at the primary school level. If this problem is to be overcome, suitable measures would have to be adopted for building up a pool of teachers who at any given time would be ready to serve in schools which may be requiring their services. Table 1.1.2 Administrative Divisions of the State Sl. Name of Name of Civil Name of Towns Name of Community No Districts Subdivisions Rural Development Blocks 1. -

ENVIS RP Centre NEHU Shillong | Newsletter Vol1 | Issue2 | March 2018VOLUME1 – May ||2018 ISSUE2 || MARCH 2018 – MAY Page2018 1 EDITORIAL 2

Contents ENVIS RP Centre NEHU Shillong | Newsletter Vol1 | Issue2 | March 2018VOLUME1 – May ||2018 ISSUE2 || MARCH 2018 – MAY Page2018 1 EDITORIAL 2 INTRODUCTION 2 CURRENT WASTE MANAGEMENT PRACTICES IN MEGHALAYA 2 ENVIS RP Centre FIELD VISIT/ CAMPAIGN: SHILLONG CITY 4 NORTH EASTERN HILL UNIVERSITY (NEHU) SHILLONG MUNICIPAL BOARD: A BRIEF REVIEW 4 SHILLONG, MEGHALAYA SMB REPORT 7 Newsletter CONCLUSION 9 NEWS 9 NEHU ENVIS RP CENTRE ACTIVITIES 11 SSOOLLIIDD WWaassttee MMaannaaggeemmeenntt PPrraaccttiicceess iinn Meghalaya Editorial Team Published by • Dr. Dinesh Bhatia, Coordinator ENVIS Resource Partner Centre NEHU, Shillong – 793022, • Prof. Dibyendu Paul, Co-Coordinator Meghalaya • Ibanrihun Thangkhiew, Programme Officer • Everly Marweiñ, Information Officer • Balaphira Majaw, Information Technology Officer Sponsored by Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change, • Fancyful Gassah, Data Entry Operator Government of India Page 2 ENVIS RP Centre NEHU Shillong | Newsletter Vol1 | Issue2 | March 2018 – May 2018 Editorial Solid Waste Management (SWM) is the process of collection, treatment and disposing of discarded solid material. Improper handling and disposal of solid waste creates unsanitary conditions that lead to pollution of the environment and outbreak of diseases. The essential objective of SWM is to reduce and eliminate adverse impacts of squander materials on human well-being and to the environment. The Government of India plays a vital role to define approach rules and gives specialized help to different States of the country whenever is needed. One of the most obvious impacts of rapidly increasing urbanization and economic development can be witnessed in the form of heaps of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) lying in dumping sites near several cities and towns. SWM is everybody's responsibility.