The USCF Elo Rating System by Steven Craig Miller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Should That It Was Not a Cheap Check Or Spite Check Be Better Collaboration Amongst the Federations to Gain Seconds

Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Chris Ross.........................................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine We catch up with Britain’s leading visually-impaired player Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein The King of Wijk...................................................................................................8 Website: www.chess.co.uk Yochanan Afek watched Magnus Carlsen win Wijk for a sixth time Subscription Rates: United Kingdom A Good Start......................................................................................................18 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Gawain Jones was pleased to begin well at Wijk aan Zee 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 3 year (36 issues) £125 How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................20 Europe Daniel King pays tribute to the legendary Viswanathan Anand 1 year (12 issues) £60 All Tied Up on the Rock..................................................................................24 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 3 year (36 issues) £165 John Saunders had to work hard, but once again enjoyed Gibraltar USA & Canada Rocking the Rock ..............................................................................................26 -

Elo World, a Framework for Benchmarking Weak Chess Engines

Elo World, a framework for with a rating of 2000). If the true outcome (of e.g. a benchmarking weak chess tournament) doesn’t match the expected outcome, then both player’s scores are adjusted towards values engines that would have produced the expected result. Over time, scores thus become a more accurate reflection DR. TOM MURPHY VII PH.D. of players’ skill, while also allowing for players to change skill level. This system is carefully described CCS Concepts: • Evaluation methodologies → Tour- elsewhere, so we can just leave it at that. naments; • Chess → Being bad at it; The players need not be human, and in fact this can facilitate running many games and thereby getting Additional Key Words and Phrases: pawn, horse, bishop, arbitrarily accurate ratings. castle, queen, king The problem this paper addresses is that basically ACH Reference Format: all chess tournaments (whether with humans or com- Dr. Tom Murphy VII Ph.D.. 2019. Elo World, a framework puters or both) are between players who know how for benchmarking weak chess engines. 1, 1 (March 2019), to play chess, are interested in winning their games, 13 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/nnnnnnn.nnnnnnn and have some reasonable level of skill. This makes 1 INTRODUCTION it hard to give a rating to weak players: They just lose every single game and so tend towards a rating Fiddly bits aside, it is a solved problem to maintain of −∞.1 Even if other comparatively weak players a numeric skill rating of players for some game (for existed to participate in the tournament and occasion- example chess, but also sports, e-sports, probably ally lose to the player under study, it may still be dif- also z-sports if that’s a thing). -

Elo and Glicko Standardised Rating Systems by Nicolás Wiedersheim Sendagorta Introduction “Manchester United Is a Great Team” Argues My Friend

Elo and Glicko Standardised Rating Systems by Nicolás Wiedersheim Sendagorta Introduction “Manchester United is a great team” argues my friend. “But it will never be better than Manchester City”. People rate everything, from films and fashion to parks and politicians. It’s usually an effortless task. A pool of judges quantify somethings value, and an average is determined. However, what if it’s value is unknown. In this scenario, economists turn to auction theory or statistical rating systems. “Skill” is one of these cases. The Elo and Glicko rating systems tend to be the go-to when quantifying skill in Boolean games. Elo Rating System Figure 1: Arpad Elo As I started playing competitive chess, I came across the Figure 2: Top Elo Ratings for 2014 FIFA World Cup Elo rating system. It is a method of calculating a player’s relative skill in zero-sum games. Quantifying ability is helpful to determine how much better some players are, as well as for skill-based matchmaking. It was devised in 1960 by Arpad Elo, a professor of Physics and chess master. The International Chess Federation would soon adopt this rating system to divide the skill of its players. The algorithm’s success in categorising people on ability would start to gain traction in other win-lose games; Association football, NBA, and “esports” being just some of the many examples. Esports are highly competitive videogames. The Elo rating system consists of a formula that can determine your quantified skill based on the outcome of your games. The “skill” trend follows a gaussian bell curve. -

Extensions of the Elo Rating System for Margin of Victory

Extensions of the Elo Rating System for Margin of Victory MathSport International 2019 - Athens, Greece Stephanie Kovalchik 1 / 46 2 / 46 3 / 46 4 / 46 5 / 46 6 / 46 7 / 46 How Do We Make Match Forecasts? 8 / 46 It Starts with Player Ratings Assume the the ith player has some true ability θi. Models of player abilities assume game outcomes are a function of the difference in abilities Prob(Wij = 1) = F(θi − θj) 9 / 46 Paired Comparison Models Bradley-Terry models are a general class of paired comparison models of latent abilities with a logistic function for win probabilities. 1 F(θi − θj) = 1 + α−(θi−θj) With BT, player abilities are treated as Hxed in time which is unrealistic in most cases. 10 / 46 Bobby Fischer 11 / 46 Fischer's Meteoric Rise 12 / 46 Arpad Elo 13 / 46 In His Own Words 14 / 46 Ability is a Moving Target 15 / 46 Standard Elo Can be broken down into two steps: 1. Estimate (E-Step) 2. Update (U-Step) 16 / 46 Standard Elo E-Step For tth match of player i against player j, the chance that player i wins is estimated as, 1 W^ ijt = 1 + 10−(Rit−Rjt)/σ 17 / 46 Elo Derivation Elo supposed that the ratings of any two competitors were independent and normal with shared standard deviation δ. Given this, he likened the chance of a win to the chance of observing a difference in ratings for ratings drawn from the same distribution, 2 Rit − Rjt ∼ N(0, 2δ ) which leads to, Rit − Rjt P(Rit − Rjt > 0) = Φ( ) √2δ and ≈ 1/(1 + 10−(Rit−Rjt)/2δ) Elo's formula was just a hack for the cumulative normal density function. -

Package 'Playerratings'

Package ‘PlayerRatings’ March 1, 2020 Version 1.1-0 Date 2020-02-28 Title Dynamic Updating Methods for Player Ratings Estimation Author Alec Stephenson and Jeff Sonas. Maintainer Alec Stephenson <[email protected]> Depends R (>= 3.5.0) Description Implements schemes for estimating player or team skill based on dynamic updating. Implemented methods include Elo, Glicko, Glicko-2 and Stephenson. Contains pdf documentation of a reproducible analysis using approximately two million chess matches. Also contains an Elo based method for multi-player games where the result is a placing or a score. This includes zero-sum games such as poker and mahjong. LazyData yes License GPL-3 NeedsCompilation yes Repository CRAN Date/Publication 2020-03-01 15:50:06 UTC R topics documented: aflodds . .2 elo..............................................3 elom.............................................5 fide .............................................7 glicko . .9 glicko2 . 11 hist.rating . 13 kfide............................................. 14 kgames . 15 krating . 16 kriichi . 17 1 2 aflodds metrics . 17 plot.rating . 19 predict.rating . 20 riichi . 22 steph . 23 Index 26 aflodds Australian Football Game Results and Odds Description The aflodds data frame has 675 rows and 9 variables. It shows the results and betting odds for 675 Australian football games played by 18 teams from 26th March 2009 until 24th June 2012. Usage aflodds Format This data frame contains the following columns: Date A date object showing the date of the game. Week The number of weeks since 25th March 2009. HomeTeam The home team name. AwayTeam The away team name. HomeScore The home team score. AwayScore The home team score. Score A numeric vector giving the value one, zero or one half for a home win, an away win or a draw respectively. -

Intrinsic Chess Ratings 1 Introduction

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Central Archive at the University of Reading Intrinsic Chess Ratings Kenneth W. Regan ∗ Guy McC. Haworth University at Buffalo University of Reading, UK February 12, 2011 Abstract This paper develops and tests formulas for representing playing strength at chess by the quality of moves played, rather than the results of games. Intrinsic quality is estimated via evaluations given by computer chess programs run to high depth, ideally whose playing strength is sufficiently far ahead of the best human players as to be a “relatively omniscient” guide. Several formulas, each having intrinsic skill parameters s for “sensitivity” and c for “competence,” are argued theoretically and tested by regression on large sets of tournament games played by humans of varying strength as measured by the internationally standard Elo rating system. This establishes a correspondence between Elo rating and the parame- ters. A smooth correspondence is shown between statistical results and the century points on the Elo scale, and ratings are shown to have stayed quite constant over time (i.e., little or no “inflation”). By modeling human players of various strengths, the model also enables distributional prediction to detect cheating by getting com- puter advice during games. The theory and empirical results are in principle trans- ferable to other rational-choice settings in which the alternatives have well-defined utilities, but bounded information and complexity constrain the perception of the utilitiy values. 1 Introduction Player strength ratings in chess and other games of strategy are based on the results of games, and are subject to both luck when opponents blunder and drift in the player pool. -

Alberto Santini Monte Dei Paschi Di Siena Outline

Chess betting odds Alberto Santini Monte dei Paschi di Siena Outline ● What is chess-bet? ● Chess rating, expected score, team events, odds. ● Anatomy of chess-bet app. ● How to build a Shiny app. ● A few hours (!?) later... What is chess-bet? chess-bet is a web app, implementing a model to calculate the odds for the players and the teams in chess events. With R and Shiny. Credits to Peter Zhdanov Team events: beating the bookmakers?! Chess rating and expected score The Elo rating system is a method for calculating the relative skill levels of players in two-player games such as chess. It is named after its creator Arpad Elo, a Hungarian-born American physics professor. Expected score: source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elo_rating_system Team events and odds Usually there are two teams composed of four chess players each. This is typical for the Chess Olympiad, World Team Chess Championship and other important events. How high is the probability that team A will win? How probable is a draw? Team B’s victory? Anatomy of chess-bet app 1. Calculate the rating differences on each board and find out the expected score of the player. 2. Find out the expected probability of a win, draw and loss in each game. 3. Repeat steps 1 and 2 for all the four boards in the team. 4. Then calculate the probabilities of all the outcomes of Team 1’s victories (and draws) and add them up. Model details - I Score EloExpectedScore <- function(rating1, rating2) { 1 / (1 + 10 ^ ((rating2 - rating1) / 400)) } Game probability getProb <- function(score, winPerc, drawPerc) { x <- score / (winPerc + 0.5 * drawPerc) win <- winPerc * x draw <- (score - win) * 2 loss <- 1 - win - draw c(win, draw, loss) } Model details - II Player profile getPlayerProfile <- function(player) { fideRatingsUrl <- "http://ratings.fide.com/search.phtml?search=" playerUrl <- paste(fideRatingsUrl, "'", player, "'", sep="") tables <- readHTMLTable(playerUrl) table <- tables[[1]] card <- getIntegerfromFactor(table[6, 1]) player <- as.character(table[6, 2]) rating <- getIntegerfromFactor(table[6, 7]) .. -

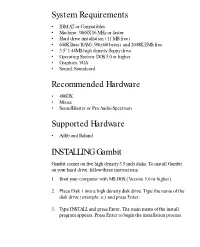

System Requirements Recommended Hardware Supported Hardware

System Requirements • IBM AT or Compatibles • Machine: 386SX 16 MHz or faster • Hard drive installation (11 MB free) • 640K Base RAM (590,000 bytes) and 2048K EMS free • 3.5” 1.44MB high density floppy drive • Operating System: DOS 5.0 or higher • Graphics: VGA • Sound: Soundcard Recommended Hardware • 486DX • Mouse • SoundBlaster or Pro Audio Spectrum Supported Hardware • Adlib and Roland INSTALLING Gambit Gambit comes on five high density 3.5 inch disks. To install Gambit on your hard drive, follow these instructions: 1. Boot your computer with MS-DOS (Version 5.0 or higher). 2. Place Disk 1 into a high density disk drive. Type the name of the disk drive (example: a:) and press Enter. 3. Type INSTALL and press Enter. The main menu of the install program appears. Press Enter to begin the installation process. 4. When Disk 1 has been installed, the program requests Disk 2. Remove Disk 1 from the floppy drive, insert Disk 2, and press Enter. 5. Follow the above process until you have installed all five disks. The Main Menu appears. Select Configure Digital Sound Device from the Main Menu and press Enter. Now choose your sound card by scrolling to it with the highlight bar and pressing Enter. Note: You may have to set the Base Address, IRQ and DMA channel manually by pressing “C” in the Sound Driver Selection menu. After you’ve chosen your card, press Enter. 6. Select Configure Music Sound Device from the Main Menu and press Enter. Now choose your music card by scrolling to it with the highlight bar and pressing Enter. -

A Brief Comparison Guide Between the ELO and the Glicko Rating Systems

A brief comparison guide between the ELO and the Glicko rating systems By Michalis Kaloumenos Member of FIDE Qualification Commission The ELO rating system The Glicko rating system Rating points Rating points in both systems is a unique characteristic of each player’s playing strength. Each finished game in a FIDE rated tournament provides a positive or negative or zero rating change. Rating remains unchanged for as long as a player remains inactive. Reliability of a player’s rating The ELO rating is considered reliable The Glicko system introduces a new value regardless of a player’s inactivity, game associated with each player called ‘rating results or strength of opponents. deviation’ which measures the reliability of a player’s rating. It provides an indication of a player’s expected performance with 95% confidence within the interval [R-2xRD, R+2xRD]. Rating deviation increases due to inactivity and decreases after game results are submitted. It is responsible for the gravity of a result when the opponent’s rating change is calculated. It also determines the development coefficient of a player’s rating. Publication of the rating list ELO rating and the development coefficient Both the Glicko rating and the rating factor K associated with each player, need to deviation need to be published in every rating be published in every list. Other values list. Both values are required for next associated with each player such as title and period’s calculations. number of games are not required for next period’s calculations. Frequency of publication Today the ELO rating list is published on a Optimum frequency of the Glicko rating list bi-monthly basis. -

Glossary of Chess

Glossary of chess See also: Glossary of chess problems, Index of chess • X articles and Outline of chess • This page explains commonly used terms in chess in al- • Z phabetical order. Some of these have their own pages, • References like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of chess-related games, see Chess variants. 1 A Contents : absolute pin A pin against the king is called absolute since the pinned piece cannot legally move (as mov- ing it would expose the king to check). Cf. relative • A pin. • B active 1. Describes a piece that controls a number of • C squares, or a piece that has a number of squares available for its next move. • D 2. An “active defense” is a defense employing threat(s) • E or counterattack(s). Antonym: passive. • F • G • H • I • J • K • L • M • N • O • P Envelope used for the adjournment of a match game Efim Geller • Q vs. Bent Larsen, Copenhagen 1966 • R adjournment Suspension of a chess game with the in- • S tention to finish it later. It was once very common in high-level competition, often occurring soon af- • T ter the first time control, but the practice has been • U abandoned due to the advent of computer analysis. See sealed move. • V adjudication Decision by a strong chess player (the ad- • W judicator) on the outcome of an unfinished game. 1 2 2 B This practice is now uncommon in over-the-board are often pawn moves; since pawns cannot move events, but does happen in online chess when one backwards to return to squares they have left, their player refuses to continue after an adjournment. -

Predicting Chess Player Strength from Game Annotations

Picking the Amateur’s Mind – Predicting Chess Player Strength from Game Annotations Christian Scheible Hinrich Schutze¨ Institute for Natural Language Processing Center for Information University of Stuttgart, Germany and Language Processing [email protected] University of Munich, Germany Abstract Results from psychology show a connection between a speaker’s expertise in a task and the lan- guage he uses to talk about it. In this paper, we present an empirical study on using linguistic evidence to predict the expertise of a speaker in a task: playing chess. Instructional chess litera- ture claims that the mindsets of amateur and expert players differ fundamentally (Silman, 1999); psychological science has empirically arrived at similar results (e.g., Pfau and Murphy (1988)). We conduct experiments on automatically predicting chess player skill based on their natural lan- guage game commentary. We make use of annotated chess games, in which players provide their own interpretation of game in prose. Based on a dataset collected from an online chess forum, we predict player strength through SVM classification and ranking. We show that using textual and chess-specific features achieves both high classification accuracy and significant correlation. Finally, we compare ourfindings to claims from the chess literature and results from psychology. 1 Introduction It has been recognized that the language used when describing a certain topic or activity may differ strongly depending on the speaker’s level of expertise. As shown in empirical experiments in psychology (e.g., Solomon (1990), Pfau and Murphy (1988)), a speaker’s linguistic choices are influenced by the way he thinks about the topic. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7.496,943 B1 Goldberg Et Al

USOO7496943B1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7.496,943 B1 Goldberg et al. (45) Date of Patent: Feb. 24, 2009 (54) NETWORKSYSTEM FOR PRESENTING 4,186,413 A 1/1980 Mortimer .................... 358,146 ADVERTISING (75) Inventors: Sheldon F. Goldberg, Henderson, NV (Continued) (US); John Van Antwerp, Springdale, MD (US) FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (73) Assignee: Beneficial Innovations, Inc., Las Vegas, DE T33983 4/1943 .................... 21/72 NV (US) (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this (Continued) past list: sited under 35 OTHER PUBLICATIONS U.S. Patent Application: Auxier et al., “Interactive Information Super (21) Appl. No.: 09/502,285 Highway Prize Network”. Sep. 2, 1994. (22) Filed: Feb. 11, 2000 (Continued) Related U.S. Application Data Primary Examiner Dmitry Suhol Assistant Examiner—Robert Mosser (63) Continuation of application No. 09/105,401, filed on (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm—Sheridan Ross P.C. Jun. 26, 1998, now Pat. No. 6,183,366, which is a continuation of application No. 08/759.895, filed on (57) ABSTRACT Dec. 3, 1996, now Pat. No. 5,823,879. (60) Provisional application No. 60/010,703, filed on Jan. A networked system is disclosed for presenting advertising 26, 1996, provisional application No. 60/010,361, during on-line interactions between a user and a service of a filed on Jan. 19, 1996. network (e.g., the Internet, interactive cable, and/or a LAN). (51) Int. Cl. Advertisements (ads) are presented to a networked user unre H04H 9/00 (2006.01) questedly during user interactions with the service. The user A63F II/00 (2006.01) Ca activate the ads (via hyperlinks) for receiving additional G06O 30/00 (2006.01) advertising.