Predicting Chess Player Strength from Game Annotations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Kings and Pawns

OF KINGS AND PAWNS CHESS STRATEGY IN THE ENDGAME ERIC SCHILLER Universal Publishers Boca Raton • 2006 Of Kings and Pawns: Chess Strategy in the Endgame Copyright © 2006 Eric Schiller All rights reserved. Universal Publishers Boca Raton , Florida USA • 2006 ISBN: 1-58112-909-2 (paperback) ISBN: 1-58112-910-6 (ebook) Universal-Publishers.com Preface Endgames with just kings and pawns look simple but they are actually among the most complicated endgames to learn. This book contains 26 endgame positions in a unique format that gives you not only the starting position, but also a critical position you should use as a target. Your workout consists of looking at the starting position and seeing if you can figure out how you can reach the indicated target position. Although this hint makes solving the problems easier, there is still plenty of work for you to do. The positions have been chosen for their instructional value, and often combined many different themes. You’ll find examples of the horse race, the opposition, zugzwang, stalemate and the importance of escorting the pawn with the king marching in front, among others. When you start out in chess, king and pawn endings are not very important because usually there is a great material imbalance at the end of the game so one side is winning easily. However, as you advance through chess you’ll find that these endgame positions play a great role in determining the outcome of the game. It is critically important that you understand when a single pawn advantage or positional advantage will lead to a win and when it will merely wind up drawn with best play. -

I Make This Pledge to You Alone, the Castle Walls Protect Our Back That I Shall Serve Your Royal Throne

AMERA M. ANDERSEN Battlefield of Life “I make this pledge to you alone, The castle walls protect our back that I shall serve your royal throne. and Bishops plan for their attack; My silver sword, I gladly wield. a master plan that is concealed. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. With knights upon their mighty steed For chess is but a game of life the front line pawns have vowed to bleed and I your Queen, a loving wife and neither Queen shall ever yield. shall guard my liege and raise my shield Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight time eight the battlefield.” Apathy Checkmate I set my moves up strategically, enemy kings are taken easily Knights move four spaces, in place of bishops east of me Communicate with pawns on a telepathic frequency Smash knights with mics in militant mental fights, it seems to be An everlasting battle on the 64-block geometric metal battlefield The sword of my rook, will shatter your feeble battle shield I witness a bishop that’ll wield his mystic sword And slaughter every player who inhabits my chessboard Knight to Queen’s three, I slice through MCs Seize the rook’s towers and the bishop’s ministries VISWANATHAN ANAND “Confidence is very important—even pretending to be confident. If you make a mistake but do not let your opponent see what you are thinking, then he may overlook the mistake.” Public Enemy Rebel Without A Pause No matter what the name we’re all the same Pieces in one big chess game GERALD ABRAHAMS “One way of looking at chess development is to regard it as a fight for freedom. -

Here Should That It Was Not a Cheap Check Or Spite Check Be Better Collaboration Amongst the Federations to Gain Seconds

Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Chris Ross.........................................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine We catch up with Britain’s leading visually-impaired player Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein The King of Wijk...................................................................................................8 Website: www.chess.co.uk Yochanan Afek watched Magnus Carlsen win Wijk for a sixth time Subscription Rates: United Kingdom A Good Start......................................................................................................18 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Gawain Jones was pleased to begin well at Wijk aan Zee 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 3 year (36 issues) £125 How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................20 Europe Daniel King pays tribute to the legendary Viswanathan Anand 1 year (12 issues) £60 All Tied Up on the Rock..................................................................................24 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 3 year (36 issues) £165 John Saunders had to work hard, but once again enjoyed Gibraltar USA & Canada Rocking the Rock ..............................................................................................26 -

Lessons Learned: a Security Analysis of the Internet Chess Club

Lessons Learned: A Security Analysis of the Internet Chess Club John Black Martin Cochran Ryan Gardner University of Colorado Department of Computer Science UCB 430 Boulder, CO 80309 USA [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract between players. Each move a player made was transmit- ted (in the clear) to an ICS server, which would then relay The Internet Chess Club (ICC) is a popular online chess that move to the opponent. The server enforced the rules of server with more than 30,000 members worldwide including chess, recorded the position of the game after each move, various celebrities and the best chess players in the world. adjusted the ratings of the players according to the outcome Although the ICC website assures its users that the security of the game, and so forth. protocol used between client and server provides sufficient Serious chess players use a pair of clocks to enforce security for sensitive information to be transmitted (such as the requirement that players move in a reasonable amount credit card numbers), we show this is not true. In partic- of time: suppose Alice is playing Bob; at the beginning ular we show how a passive adversary can easily read all of a game, each player is allocated some number of min- communications with a trivial amount of computation, and utes. When Alice is thinking, her time ticks down; after how an active adversary can gain virtually unlimited pow- she moves, Bob begins thinking as his time ticks down. If ers over an ICC user. -

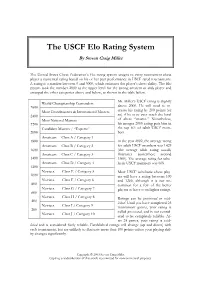

The USCF Elo Rating System by Steven Craig Miller

The USCF Elo Rating System By Steven Craig Miller The United States Chess Federation’s Elo rating system assigns to every tournament chess player a numerical rating based on his or her past performance in USCF rated tournaments. A rating is a number between 0 and 3000, which estimates the player’s chess ability. The Elo system took the number 2000 as the upper level for the strong amateur or club player and arranged the other categories above and below, as shown in the table below. Mr. Miller’s USCF rating is slightly World Championship Contenders 2600 above 2000. He will need to in- Most Grandmasters & International Masters crease his rating by 200 points (or 2400 so) if he is to ever reach the level Most National Masters of chess “master.” Nonetheless, 2200 his meager 2000 rating puts him in Candidate Masters / “Experts” the top 6% of adult USCF mem- 2000 bers. Amateurs Class A / Category 1 1800 In the year 2002, the average rating Amateurs Class B / Category 2 for adult USCF members was 1429 1600 (the average adult rating usually Amateurs Class C / Category 3 fluctuates somewhere around 1400 1500). The average rating for scho- Amateurs Class D / Category 4 lastic USCF members was 608. 1200 Novices Class E / Category 5 Most USCF scholastic chess play- 1000 ers will have a rating between 100 Novices Class F / Category 6 and 1200, although it is not un- 800 common for a few of the better Novices Class G / Category 7 players to have even higher ratings. 600 Novices Class H / Category 8 Ratings can be provisional or estab- 400 lished. -

Elo World, a Framework for Benchmarking Weak Chess Engines

Elo World, a framework for with a rating of 2000). If the true outcome (of e.g. a benchmarking weak chess tournament) doesn’t match the expected outcome, then both player’s scores are adjusted towards values engines that would have produced the expected result. Over time, scores thus become a more accurate reflection DR. TOM MURPHY VII PH.D. of players’ skill, while also allowing for players to change skill level. This system is carefully described CCS Concepts: • Evaluation methodologies → Tour- elsewhere, so we can just leave it at that. naments; • Chess → Being bad at it; The players need not be human, and in fact this can facilitate running many games and thereby getting Additional Key Words and Phrases: pawn, horse, bishop, arbitrarily accurate ratings. castle, queen, king The problem this paper addresses is that basically ACH Reference Format: all chess tournaments (whether with humans or com- Dr. Tom Murphy VII Ph.D.. 2019. Elo World, a framework puters or both) are between players who know how for benchmarking weak chess engines. 1, 1 (March 2019), to play chess, are interested in winning their games, 13 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/nnnnnnn.nnnnnnn and have some reasonable level of skill. This makes 1 INTRODUCTION it hard to give a rating to weak players: They just lose every single game and so tend towards a rating Fiddly bits aside, it is a solved problem to maintain of −∞.1 Even if other comparatively weak players a numeric skill rating of players for some game (for existed to participate in the tournament and occasion- example chess, but also sports, e-sports, probably ally lose to the player under study, it may still be dif- also z-sports if that’s a thing). -

PGN/AN Verification for Legal Chess Gameplay

PGN/AN Verification for Legal Chess Gameplay Neil Shah Guru Prashanth [email protected] [email protected] May 10, 2015 Abstract Chess has been widely regarded as one of the world's most popular games through the past several centuries. One of the modern ways in which chess games are recorded for analysis is through the PGN/AN (Portable Game Notation/Algebraic Notation) standard, which enforces a strict set of rules for denoting moves made by each player. In this work, we examine the use of PGN/AN to record and describe moves with the intent of building a system to verify PGN/AN in order to check for validity and legality of chess games. To do so, we formally outline the abstract syntax of PGN/AN movetext and subsequently define denotational state-transition and associated termination semantics of this notation. 1 Introduction Chess is a two-player strategy board game which is played on an eight-by-eight checkered board with 64 squares. There are two players (playing with white and black pieces, respectively), which move in alternating fashion. Each player starts the game with a total of 16 pieces: one king, one queen, two rooks, two knights, two bishops and eight pawns. Each of the pieces moves in a different fashion. The game ends when one player checkmates the opponents' king by placing it under threat of capture, with no defensive moves left playable by the losing player. Games can also end with a player's resignation or mutual stalemate/draw. We examine the particulars of piece movements later in this paper. -

ANALYSIS and IMPLEMENTATION of the GAME ARIMAA Christ-Jan

ANALYSIS AND IMPLEMENTATION OF THE GAME ARIMAA Christ-Jan Cox Master Thesis MICC-IKAT 06-05 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE OF KNOWLEDGE ENGINEERING IN THE FACULTY OF GENERAL SCIENCES OF THE UNIVERSITEIT MAASTRICHT Thesis committee: prof. dr. H.J. van den Herik dr. ir. J.W.H.M. Uiterwijk dr. ir. P.H.M. Spronck dr. ir. H.H.L.M. Donkers Universiteit Maastricht Maastricht ICT Competence Centre Institute for Knowledge and Agent Technology Maastricht, The Netherlands March 2006 II Preface The title of my M.Sc. thesis is Analysis and Implementation of the Game Arimaa. The research was performed at the research institute IKAT (Institute for Knowledge and Agent Technology). The subject of research is the implementation of AI techniques for the rising game Arimaa, a two-player zero-sum board game with perfect information. Arimaa is a challenging game, too complex to be solved with present means. It was developed with the aim of creating a game in which humans can excel, but which is too difficult for computers. I wish to thank various people for helping me to bring this thesis to a good end and to support me during the actual research. First of all, I want to thank my supervisors, Prof. dr. H.J. van den Herik for reading my thesis and commenting on its readability, and my daily advisor dr. ir. J.W.H.M. Uiterwijk, without whom this thesis would not have been reached the current level and the “accompanying” depth. The other committee members are also recognised for their time and effort in reading this thesis. -

Kasparov's Nightmare!! Bobby Fischer Challenges IBM to Simul IBM

California Chess Journal Volume 20, Number 2 April 1st 2004 $4.50 Kasparov’s Nightmare!! Bobby Fischer Challenges IBM to Simul IBM Scrambles to Build 25 Deep Blues! Past Vs Future Special Issue • Young Fischer Fires Up S.F. • Fischer commentates 4 Boyscouts • Building your “Super Computer” • Building Fischer’s Dream House • Raise $500 playing chess! • Fischer Articles Galore! California Chess Journal Table of Con tents 2004 Cal Chess Scholastic Championships The annual scholastic tourney finishes in Santa Clara.......................................................3 FISCHER AND THE DEEP BLUE Editor: Eric Hicks Contributors: Daren Dillinger A miracle has happened in the Phillipines!......................................................................4 FM Eric Schiller IM John Donaldson Why Every Chess Player Needs a Computer Photographers: Richard Shorman Some titles speak for themselves......................................................................................5 Historical Consul: Kerry Lawless Founding Editor: Hans Poschmann Building Your Chess Dream Machine Some helpful hints when shopping for a silicon chess opponent........................................6 CalChess Board Young Fischer in San Francisco 1957 A complet accounting of an untold story that happened here in the bay area...................12 President: Elizabeth Shaughnessy Vice-President: Josh Bowman 1957 Fischer Game Spotlight Treasurer: Richard Peterson One game from the tournament commentated move by move.........................................16 Members at -

A GUIDE to SCHOLASTIC CHESS (11Th Edition Revised June 26, 2021)

A GUIDE TO SCHOLASTIC CHESS (11th Edition Revised June 26, 2021) PREFACE Dear Administrator, Teacher, or Coach This guide was created to help teachers and scholastic chess organizers who wish to begin, improve, or strengthen their school chess program. It covers how to organize a school chess club, run tournaments, keep interest high, and generate administrative, school district, parental and public support. I would like to thank the United States Chess Federation Club Development Committee, especially former Chairman Randy Siebert, for allowing us to use the framework of The Guide to a Successful Chess Club (1985) as a basis for this book. In addition, I want to thank FIDE Master Tom Brownscombe (NV), National Tournament Director, and the United States Chess Federation (US Chess) for their continuing help in the preparation of this publication. Scholastic chess, under the guidance of US Chess, has greatly expanded and made it possible for the wide distribution of this Guide. I look forward to working with them on many projects in the future. The following scholastic organizers reviewed various editions of this work and made many suggestions, which have been included. Thanks go to Jay Blem (CA), Leo Cotter (CA), Stephan Dann (MA), Bob Fischer (IN), Doug Meux (NM), Andy Nowak (NM), Andrew Smith (CA), Brian Bugbee (NY), WIM Beatriz Marinello (NY), WIM Alexey Root (TX), Ernest Schlich (VA), Tim Just (IL), Karis Bellisario and many others too numerous to mention. Finally, a special thanks to my wife, Susan, who has been patient and understanding. Dewain R. Barber Technical Editor: Tim Just (Author of My Opponent is Eating a Doughnut and Just Law; Editor 5th, 6th and 7th editions of the Official Rules of Chess). -

Elo and Glicko Standardised Rating Systems by Nicolás Wiedersheim Sendagorta Introduction “Manchester United Is a Great Team” Argues My Friend

Elo and Glicko Standardised Rating Systems by Nicolás Wiedersheim Sendagorta Introduction “Manchester United is a great team” argues my friend. “But it will never be better than Manchester City”. People rate everything, from films and fashion to parks and politicians. It’s usually an effortless task. A pool of judges quantify somethings value, and an average is determined. However, what if it’s value is unknown. In this scenario, economists turn to auction theory or statistical rating systems. “Skill” is one of these cases. The Elo and Glicko rating systems tend to be the go-to when quantifying skill in Boolean games. Elo Rating System Figure 1: Arpad Elo As I started playing competitive chess, I came across the Figure 2: Top Elo Ratings for 2014 FIFA World Cup Elo rating system. It is a method of calculating a player’s relative skill in zero-sum games. Quantifying ability is helpful to determine how much better some players are, as well as for skill-based matchmaking. It was devised in 1960 by Arpad Elo, a professor of Physics and chess master. The International Chess Federation would soon adopt this rating system to divide the skill of its players. The algorithm’s success in categorising people on ability would start to gain traction in other win-lose games; Association football, NBA, and “esports” being just some of the many examples. Esports are highly competitive videogames. The Elo rating system consists of a formula that can determine your quantified skill based on the outcome of your games. The “skill” trend follows a gaussian bell curve. -

E-Magazine July 2020

E-MAGAZINE JULY 2020 0101 #EOCC2020 European Online Corporate Championships announced for 3 & 4 of October #EOYCC2020 European Online Youth Chess Championhsip announced for 18-20 September. International Chess Day recognised by United Nations & UNESCO celebrated all over the World #InternationalChessDay On, 20th of July, World celebrates the #InternationalChessDay. The International Chess Federation (FIDE) was founded, 96 years ago on 20th July 1924. The idea to celebrate this day as the International Chess Day was proposed by UNESCO, and it has been celebrated as such since 1966. On December 12, 2019, the UN General Assembly unanimously approved a resolution recognising the World Chess Day. On the occasion of the International Chess Day, a tele-meeting between the United Nations and FIDE was held on 20th of July 2020. Top chess personalities and representatives of the U.N. gathered to exchange views and insights to strengthen the productive collaboration European Chess Union has its seat in Switzerland, Address: Rainweidstrasse 2, CH-6333, Hunenberg See, Switzerland ECU decided to make a special promotional #Chess video. Mr. European Chess Union is an independent Zurab Azmaiparashvili visited the Georgian most popular Musical association founded in 1985 in Graz, Austria; Competition Show “Big stage”.ECU President taught the judges of European Chess Union has 54 National Federation Members; Every year ECU organizes more than 20 show, famous artists, how to play chess and then played a game with prestigious events and championships. them! www.europechess.org Federations, clubs, players and chess lovers took part in the [email protected] celebration all over the world.