Advance Sheets Supreme Court

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01476-Cleveland Gen Election

SAMPLE BALLOT BS1/110 OFFICIAL BALLOT FOR THE GENERAL ELECTION CLEVELAND COUNTY, NORTH CAROLINA NOVEMBER 2, 2004 GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTE, COMPLETE THE ARROW POINTING TO YOUR CHOICE, LIKE THIS: L READ ALL OTHER INSTRUCTIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE VOTING!!!! REMEMBER: VOTE BOTH SIDES OF THIS BALLOT FOR PRESIDENT AND INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTER a. To vote for all candidates of one party (a FOR LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR VICE-PRESIDENT OF THE straight party ticket), complete the arrow at UNITED STATES the right of the party for whose candidates BEVERLY EAVES PERDUE DEM you wish to vote. INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTER b. You may vote a split ticket by not completing JIM SNYDER REP a. To vote this office, complete the arrow at the the arrow at the right of the party, but by com- right of the Political Party for whose candi- pleting the arrow at the right of the name of CHRISTOPHER COLE LIB dates you wish to vote. each candidate for whom you wish to vote. b. A vote for names of a Political Party’s candi- c. You may also vote a split ticket by completing dates for President and Vice-President is a the arrow at the right of the party and then vote for the Electors of that party, the names completing the arrow to the right of the name FOR ATTORNEY GENERAL of whom are on file with the Secretary of State. of any candidate you choose of a different c. If you wish to write in the name of a qualified party. In any multi-seat race where an arrow ROY COOPER DEM write-in candidate, you must write the name in is completed to the right of a party and you the blank space provided and complete the vote for candidates of another party, you JOE KNOTT REP arrow at the right of the name in order for your must also complete the arrow to the right of vote to count. -

The Judicial Branch North Carolina’S Court System Had Many Levels Before the Judicial Branch Underwent Comprehensive Reorganization in the Late 1960S

The Judicial Branch North Carolina’s court system had many levels before the judicial branch underwent comprehensive reorganization in the late 1960s. Statewide, the N.C. Supreme Court had appellate jurisdiction, while the Superior Court had general trial jurisdiction. Hundreds of Recorder’s Courts, Domestic Relations Courts, Mayor’s Courts, County Courts and Justice of the Peace Courts created by the General Assembly existed at the local level, almost every one individually structured to meet the specific needs of the towns and counties they served. Some of these local courts stayed in session on a nearly full-time basis; others convened for only an hour or two a week. Full-time judges presided over a handful of the local courts, although most were not full-time. Some local courts had judges who had been trained as lawyers. Many, however, made do with lay judges who spent most of their time working in other careers. Salaries for judges and the overall administrative costs varied from court to court, sometimes differing even within the same county. In some instances, such as justices of the peace, court officials were compensated by the fees they exacted and they provided their own facilities. As early as 1955, certain citizens recognized the need for professionalizing and streamlining the court system in North Carolina. At the suggestion of Governor Luther Hodges and Chief Justice M.V. Barnhill, the North Carolina Bar Association sponsored an in-depth study that ultimately resulted in the restructuring of the court system. Implementing the new structure, however, required amending Article IV of the State Constitution. -

MEETING AGENDA Scheduled Attendees

DRAFT MEETING AGENDA Date: November 25, 2020 Time: 1:00 PM Location: Board of Elections Type: Special Scheduled Attendees: Thomas C. Pollard, Chair Rae Hunter-Havens, Elections Director Evelyn D. Adger, Secretary Joan Geiszler-Ludlum, Administrative Technician Jonathan W. Washburn, Member Caroline Dawkins, Elections Program & Outreach Derrick R. Miller, Member Coordinator Russ C. Bryan, Member Visitor(s): Sheryl Kelly, Assistant County Manager AGENDA ITEMS 1. Meeting Opening a. Call to Order b. Pledge of Allegiance c. Approval of Agenda 2. General Discussion Other Elections-Related Matters 3. New Business Hearing on Election Protest 4. Adjournment *Agenda packets are sent via email in advance of meetings. Item # 1c Special Meeting New Hanover County Board of Elections November 25, 2020 Subject: Approval of Agenda Summary: N/A Board Action Required: Staff recommends approval Item # 2 Special Meeting New Hanover County Board of Elections November 25, 2020 Subject: General Discussion Summary: This is an opportunity for discussion on other elections-related matters not included in the meeting agenda. Board Action Required: Discuss as necessary Item # 3a Special Meeting New Hanover County Board of Elections November 20, 2020 Subject: Hearing on Election Protest Applicable Statutes and/or Rules N.C. Gen. Stat § 163-182.10; 08 NCAC 02 .0110; 08 NCAC 02 .0114(a) Summary: On November 17, 2020, the New Hanover County Board of Elections, and 89 other counties, received an election protest regarding vote count and tabulation, and violation of election law or irregularity, consistent with N.C. Gen. Stat. §§ 163-182.9(b)(4)(a) and 163-182.9(b)(4)(c). -

Judicial Reform As a Tug of War: How Ideological Differences Between Politicians and the Bar Explain Attempts at Judicial Reform

Bonica & Sen (Do Not Delete) 11/14/2017 1:27 PM Judicial Reform as a Tug of War: How Ideological Differences Between Politicians and the Bar Explain Attempts at Judicial Reform Adam Bonica* Maya Sen** What predicts attempts at judicial reform? We develop a broad, generalizable framework that both explains and predicts attempts at judicial reform. Specifically, we explore the political tug of war created by the polarization between the bar and political actors, in tandem with existing judicial selection mechanisms. The more liberal the bar and the more conservative political actors, the greater the incentive political actors will have to introduce ideology into judicial selection. (And, vice versa, the more conservative the bar and the more liberal political actors, the greater incentive political actors will have to introduce ideology into judicial selection.) Understanding this dynamic, we argue, is key to both explaining and predicting attempts at judicial reform. For example, under most ideological configurations, conservatives will, depending on how liberal they perceive the bar to be, push reform efforts toward partisan elections and executive appointments, while liberals will work to maintain merit-oriented commissions. We explore the contours of this predictive framework with three in-depth, illustrative case studies: Florida in 2001, Kansas in the 2010s, and North Carolina in 2016. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 1782 I. JUDICIAL REFORM BACKGROUND ..................................... 1784 A. Independence and Establishment of American Courts .................................................................. 1784 * Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Stanford University. Email: [email protected]. Web: http://www.stanford.edu/~bonica [https://perma.cc/C5XD-XB5C]. ** Associate Professor, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. -

The Ali Reporter Summer 2021 3

THE QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER OF THE AMERICAN LAW INSTITUTE VOLUME 43 NUMBER 3 SUMMER 2021 THE DIRECTOR’S LETTER BY ACTIONS TAKEN AT RICHARD L. REVESZ THE ANNUAL MEETING The ALI and This year’s Annual Meeting was held on May 17 to 18 and June 7 to 8. Below is a summary of the actions taken during both segments. All approvals by the Pandemic the membership at the Annual Meeting are subject to the discussion at the Meeting and the usual editorial prerogative. The last 18 months have transformed the United States (and the rest of the world) in MONDAY, MAY 17 ways that were unimaginable in early 2020. A virulent pandemic has claimed more than THE LAW OF AMERICAN INDIANS 600,000 lives in our country alone. At the same Presented for membership approval was a Proposed Final Draft that contains time, we suffered major economic dislocations, the entire project: Chapter 1, Federal–Tribal Relations; Chapter 2, Tribal saw the cruel consequences of racial inequality, Authority; Chapter 3, State–Tribal Relations; Chapter 4, Tribal Economic witnessed the significant challenges faced by Development; Chapter 5, Indian Country Criminal Jurisdiction; and Chapter 6, our democratic institutions, and experienced Natural Resources. Membership voted to approve the Proposed Final Draft, unprecedented fires and other pernicious marking the completion of this project. See page 6 for additional information. consequences of climate change. Many of us have experienced the ravages of the pandemic COMPLIANCE AND ENFORCEMENT FOR ORGANIZATIONS in intensely personal ways, through the loss of Tentative Draft No. 2 contains Chapter 1, Definitions, some of which were family members, friends, and colleagues, and already approved at the 2019 Annual Meeting, Chapter 4, Compliance Risk worried about the future of our nation. -

OCTOBER TERM 1994 Reference Index Contents

jnl94$ind1Ð04-04-96 12:34:32 JNLINDPGT MILES OCTOBER TERM 1994 Reference Index Contents: Page Statistics ....................................................................................... II General .......................................................................................... III Appeals ......................................................................................... III Arguments ................................................................................... III Attorneys ...................................................................................... III Briefs ............................................................................................. IV Certiorari ..................................................................................... IV Costs .............................................................................................. V Judgments and Opinions ........................................................... V Original Cases ............................................................................. V Records ......................................................................................... VI Rehearings ................................................................................... VI Rules ............................................................................................. VI Stays .............................................................................................. VI Conclusion ................................................................................... -

NOTICE MEETING of the STATE BOARD of ELECTIONS the State

Mailing Address: P.O. Box 27255 Raleigh, NC 27611-7255 Phone: (919) 733-7173 Fax: (919) 715-0135 NOTICE MEETING OF THE STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS The State Board of Elections will hold a public meeting by teleconference on Wednesday, February 22, 2017 at 2:15 p.m. Interested members of the public may hear proceedings by dialing (562) 247-8422 (code: 128-956-572). Materials will be available at http://go.usa.gov/x9Jas. The meeting is called pursuant to the written petition of two or more members filed under G.S. § 163-20(a). TENTATIVE AGENDA Call to order Statement regarding ethics and conflicts of interest G.S. § 138A-15(e) Discussion regarding status of Cooper v. Berger & Moore (P 17-101; 16 CVS 15636) Resources: S.L. 2016-125 Motions for Summary Judgement: Plaintiff’s Brief Defendants’ Brief Adjourn Additional Resources: Motion to Dismiss State v. NAACP et al. (filed Feb. 21) Supreme Court Docket (updated Feb. 21 at 6:30PM) Petition for Writ of Certiorari (filed Dec. 27) Letter from Legislative Leadership (dated Feb. 21) 1/384 Separator Page Statement regarding 2/384 Statement regarding ethics: GS 138-15(e) In accordance with the State Government Ethics Act, it is the duty of every Board member to avoid both conflicts of interest and appearances of conflict. Does any Board member have any known conflict of interest or appearance of conflict with respect to any matters coming before the [Board] today? If so, please identify the conflict or appearance of conflict and refrain from any undue participation in the particular matter. -

Honorable Nathan L. Hecht Chief Justice of Texas PRESIDENT-ELECT

Last Revised June 2021 PRESIDENT: Honorable Nathan L. Hecht Chief Justice of Texas PRESIDENT-ELECT: Honorable Paul A. Suttell Chief Justice of Rhode Island ALABAMA ARKANSAS Honorable Tom Parker Honorable John Dan Kemp Chief Justice Chief Justice Alabama Supreme Court Supreme Court of Arkansas 300 Dexter Avenue Justice Building Montgomery, AL 36104-3741 625 Marshall St. (334) 229-0600 FAX (334) 229-0535 Little Rock, AR 72201 (501) 682-6873 FAX (501) 683-4006 ALASKA CALIFORNIA Honorable Joel H. Bolger Chief Justice Honorable Tani G. Cantil-Sakauye Alaska Supreme Court Chief Justice 303 K Street, 5th Floor Supreme Court of California Anchorage, AK 99501 350 McAllister Street (907) 264-0633 FAX (907) 264-0632 San Francisco, CA 94102 (415) 865-7060 FAX (415) 865-7181 AMERICAN SAMOA COLORADO Honorable F. Michael Kruse Chief Justice Honorable Brian D. Boatright The High Court of American Samoa Chief Justice Courthouse, P.O. Box 309 Colorado Supreme Court Pago Pago, AS 96799 2 East 14th Avenue 011 (684) 633-1410 FAX 011 (684) 633-1318 Denver, CO 80203-2116 (720) 625-5410 FAX (720) 271-6124 ARIZONA CONNECTICUT Honorable Robert M. Brutinel Chief Justice Honorable Richard A. Robinson Arizona Supreme Court Chief Justice 1501 W. Washington Street, Suite 433 State of Connecticut Supreme Court Phoenix, AZ 85007-3222 231 Capitol Avenue (602) 452-3531 FAX (602) 452-3917 Hartford, CT 06106 (860) 757-2113 FAX (860) 757-2214 1 Last Revised June 2021 DELAWARE HAWAII Honorable Collins J. Seitz, Jr. Honorable Mark E. Recktenwald Chief Justice Chief Justice Supreme Court of Delaware Supreme Court of Hawaii The Renaissance Centre 417 South King Street 405 N. -

Vol. 362 Front

NORTH CAROLINA REPORTS VOLUME 362 SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA 7 DECEMBER 2007 12 DECEMBER 2008 RALEIGH 2009 CITE THIS VOLUME 362 N.C. This volume is printed on permanent, acid-free paper in compliance with the North Carolina General Statutes. IN MEMORIAM JUSTICE JOHN WEBB ASSOCIATE JUSTICE 26 NOVEMBER 1986 - 30 SEPTEMBER 1998 iii IN MEMORIAM JUSTICE FRANCIS I. PARKER ASSOCIATE JUSTICE 2 SEPTEMBER 1986 - 25 NOVEMBER 1986 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Justices of the Supreme Court . vii Superior Court Judges . viii District Court Judges . xii Attorney General . xx District Attorneys . xxii Public Defenders . xxiii Table of Cases Reported . xxiv Orders of the Court . xxvi Petitions for Discretionary Review . xxvii Petitions to Rehear . xxxiii General Statutes Cited . xxxiv Constitution of United States Cited . xxxiv Rules of Evidence Cited . xxxiv Rules of Appellate Procedure Cited . xxxv Licensed Attorneys . xxxvi Opinions of the Supreme Court . 1-688 Presentation of Associate Justice James William Pless, Jr. Portrait . 693 Rules of Appellate Procedure . 699 Amendment to the Rules and Regulations of the North Carolina State Bar Concerning the Administrative Committee . 703 Amendments to the Rules and Regulations of the North Carolina State Bar Concerning the Paralegal Certification Program . 708 Amendments to the Rules and Regulations of the North Carolina State Bar Concerning Transfer to Inactive Status . 710 Amendments to the Rules and Regulations of the North Carolina State Bar Concerning the Model District Bar Bylaws . 714 v Amendments to the Rules and Regulations of the North Carolina State Bar Concerning the Practical Training of Law Students . 716 Amendments to the Rules and Regulations of the North Carolina State Bar Concerning the Continuing Legal Education Program . -

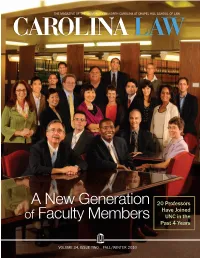

A NEW Generation of Faculty MEMBERS 20 Professors Have Joined UNC in the Past 4 Years

THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL SCHOOL OF LAW CAROLINA LAW A New Generation 20 Professors Have Joined of Faculty Members UNC in the Past 4 Years VOLUME 34, ISSUE TWO FALL/WINTER 2010 Dean’s MessaGE UNC Law Alumni Association Dear Friends: Board of Directors As dean, I am enormously proud of this cover of Carolina Law Executive Officers magazine. It showcases the 20 new faculty members we have Norma R. Houston ’89, president hired since 2006. They are all talented scholars and wonderful Ann Reed ’71, vice president teachers. Among them, we hope, are the next Bob Byrd, Gene Gressman, Dan Pollitt or Sally Sharp—Carolina Law treasures Robert A. Wicker ’69, second vice president whom many of you remember fondly. You will read in the John Charles Boger ’74, secretary-treasurer pages of this magazine about the ongoing work of these new EARS R. Scott Tobin ’81, Law Foundation chair S faculty and other faculty members whom you already know AN W. Erwin Spainhour ’70, past president (2004-05) D well. I invite you to meet these new faces and to welcome John Charles Boger Donna R. Rascoe ’93, past president (2005-06) them warmly into the Carolina Law fold. John B. McMillan ’67, past president (2006-07) Let me also share word of some wonderful student successes this past year. More than 96 percent of our departing May 2009 graduates found employment within nine months David M. Moore II ’69, past president (2007-08) of graduation, in spite of the most difficult legal hiring market in decades. -

5Th Annual AACU State Society Network Advocacy Conference

5th Annual AACU State Society Network Advocacy Conference State Society Network Leadership Richard S. Pelman, MD Arthur E. Tarantino, MD AACU President State Society SSN Chair Network Mark S. Austenfeld, MD Charles A. McWilliams, MD SSN Vice Chair SSN Advisor AACU President-Elect AACU Secretary/Treasurer September 22 - 23, 2012 Rosemont, IL 2012 AACU State Society Network Advocacy Conference TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome Message ....................................................................................................................1 Corporate Members and Attendees .......................................................................................2 Conference Supporters and Attendees .................................................................................2 Conference Attendees ..............................................................................................................3 Agenda at a Glance ...................................................................................................................5 Sessions, Speakers and Honorees ........................................................................................9 SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 2012 Urology Presidents’ Council Roundtable ...............................................................................10 Urology Joint Advocacy Coalition Update ..............................................................................12 Non-Physician Providers’ Scopes of Practice: Rowing in the Same Direction ....................14 The Role of Medical -

Vol. 362 Front

NORTH CAROLINA REPORTS VOLUME 362 SUPREME COURT OF NORTH CAROLINA 7 DECEMBER 2007 12 DECEMBER 2008 RALEIGH 2009 CITE THIS VOLUME 362 N.C. This volume is printed on permanent, acid-free paper in compliance with the North Carolina General Statutes. IN MEMORIAM JUSTICE JOHN WEBB ASSOCIATE JUSTICE 26 NOVEMBER 1986 - 30 SEPTEMBER 1998 iii IN MEMORIAM JUSTICE FRANCIS I. PARKER ASSOCIATE JUSTICE 2 SEPTEMBER 1986 - 25 NOVEMBER 1986 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Justices of the Supreme Court . vii Superior Court Judges . viii District Court Judges . xii Attorney General . xx District Attorneys . xxii Public Defenders . xxiii Table of Cases Reported . xxiv Orders of the Court . xxvi Petitions for Discretionary Review . xxvii Petitions to Rehear . xxxiii General Statutes Cited . xxxiv Constitution of United States Cited . xxxiv Rules of Evidence Cited . xxxiv Rules of Appellate Procedure Cited . xxxv Licensed Attorneys . xxxvi Opinions of the Supreme Court . 1-688 Presentation of Associate Justice James William Pless, Jr. Portrait . 693 Rules of Appellate Procedure . 699 Amendment to the Rules and Regulations of the North Carolina State Bar Concerning the Administrative Committee . 703 Amendments to the Rules and Regulations of the North Carolina State Bar Concerning the Paralegal Certification Program . 708 Amendments to the Rules and Regulations of the North Carolina State Bar Concerning Transfer to Inactive Status . 710 Amendments to the Rules and Regulations of the North Carolina State Bar Concerning the Model District Bar Bylaws . 714 v Amendments to the Rules and Regulations of the North Carolina State Bar Concerning the Practical Training of Law Students . 716 Amendments to the Rules and Regulations of the North Carolina State Bar Concerning the Continuing Legal Education Program .