A Look Behind the Veil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Or C\^Iing Party. \

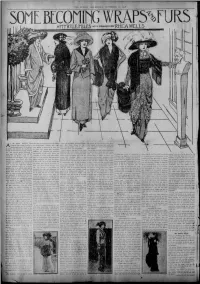

r 3 the season advances one's that they are their own excuse for being— This type is prettily developed In mole- the dismay of those observers who dislike thoughts turn toward evening en- as reconstructed emeralds and ruMes skin. Mrs. Frank Nelson, Jr., has a their fidgety movements and would fain scarf and big pillow muff of this fur enjoy the classic calm of the unbeplum- tertainments, and it is the toilette have gained a distinction of their own do soiree and de theatre that which she wears very becomingly. aged bandeau. manteau by their real beauty and excellence. There is also a scarf of tlie black One of the quaintest coiffure ornaments occupy the attention of the lady of fash- big Moreover, fur imitations are absolutely fur In Mr. Wells’ sketch. It is fitted in town is black velvet and ion. The evening gowns mentioned in lynx bright green if the sisters and I Indispensable wives, about the neck and at one end Is orna- tulle. It Is clasped in the back with a these pages from time to time and de- of something to give in celebration of Many families hold the bridal veil as one popular colors in what is known as tho daughters of others than multi-million- a of made in the mented with handsome sil£ frog, pro- narrow' hand of mother pearl, very scribed by pen pictures Christman has begun to crowd the shops. of the most precious of heirlooms, to b© “made*’ veils and these with their well aires are to be with ducing that “one-sided” effect at once thin and very lustrous. -

What Isveiling?

Muslim Women—we just can’t seem to catch a break. We’re oppressed, submissive, and forced into arranged marriages by big- bearded men. Oh, and let’s not forget—we’re also all hiding explosives under our clothes. The truth is—like most women—we’re independent and opinionated. And the only things hiding under our clothes are hearts yearning for love. Everyone seems to have an opinion about Muslim women, even those—especially those—who have never met one. —Ayesha Mattu and Nura Maznavi, introduction to Love Inshallah: The Secret Love Lives of American Muslim Women introduCtion What Is Veiling? Islam did not invent veiling, nor is veiling a practice specific to Muslims. Rather, veiling is a tradition that has existed for thousands of years, both in and far beyond the Middle East, and well before Islam came into being in the early seventh century. Throughout history and around the world, veiling has been a custom associated with “women, men, and sacred places, and objects.”1 Few Muslims and non- Muslims realize that Islam took on veiling practices already in place at the dawn of the seventh century around the Mediterranean Basin. Islam inherited them from the major empires and societies of the time along with many other customs and patriarchal traditions related to the status of women. To understand the meaning of veiling in Islam today, one must recognize the important yet neglected history of veiling practices in the pre-Isla mic period and appreciate the continuities and similarities among cultures and religious traditions. Given that veiling -

Modernist Mediums of Transcendence in Sylvia Plath's Poetry and Prose

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2003 Love, Violence, and Creation: Modernist Mediums of Transcendence in Sylvia Plath's Poetry and Prose Autumn Williams Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Williams, Autumn, "Love, Violence, and Creation: Modernist Mediums of Transcendence in Sylvia Plath's Poetry and Prose" (2003). Masters Theses. 1395. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1395 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is receiving a number of request from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow these to be copied. PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University NOT allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author's Signature Date This form must be submitted in duplicate. -

The Construction of National Culture and Identity in a Province: the Case of the People's House of Kayseri

THE CONSTRUCTION OF NATIONAL CULTURE AND IDENTITY IN A PROVINCE: THE CASE OF THE PEOPLE'S HOUSE OF KAYSERI A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY FULYA BALKAR IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF MEDIA AND CULTURAL STUDIES DECEMBER 2019 i ii Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar Kondakçı Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Lütfi Doğan Tılıç (Başkent Uni., HIT) Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan (METU, ADM) Assoc. Prof. Barış Çakmur (METU, ADM) iii ii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Fulya Balkar Signature : iii ABSTRACT THE CONSTRUCTION OF NATIONAL CULTURE AND IDENTITY IN A PROVINCE: THE CASE OF THE PEOPLE'S HOUSE OF KAYSERI Balkar, Fulya M.S., Department of Media and Cultural Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan December 2019, 249 pages This thesis focuses on the Kayseri House experience in early republican period and aims to explore how the narratives of national culture and identity were constructed in a so-called conservative province in the context of the Kayseri House. -

Section 1: Islamisation in Society

Section 1: Islamisation in Society The Islamic forces at play in Bangladeshi politics have a strength that goes beyond mere electoral achievement. They are deeply rooted in parts of society and slowly increasing their influence. To gauge this spread, this section examines four main issues: education, attitudes to women, attacks on non-Muslims and the charity sector. The process of Islamisation is pronounced in the education sector, especially in the recent mushrooming of vari- ous types of madrasa. No reliable statistics exist on how many children attend madrasa in total, but we have collected a range of numbers and estimates from official sources and present what we think is the best collation to date. This suggests up to 4 million children are being educated in 19,000 madrasa in Bangladesh at present, most of them at a primary level. The surprising aspect is that there are almost as many girls as boys in Bangladesh's madrasa. This section notes Bangladesh's substantial progress in women's development and mentions the obstacles to greater female political participation, before examining attitudes towards women's empowerment as articulated by Islamists. It is significant that new Election Commission rules require all political parties to have 30% female repre- sentation in their National Executive Committees by 2020. This poses a potential problem for the Islamic parties. Unfortunately attacks on religious minorities - Hindus, Ahmadiyya and Buddhists - are a litmus test of the spread of a particular brand of religious intolerance and lawlessness. In 2013 we have charted a dramatic increase in attacks on Hindus, after the verdicts in the war crimes trial, collating press reports from the Bengali and English press. -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

Pakistan – PAK35842 – External Advice –Women – Veil / Purdah

Country Advice Pakistan Pakistan – PAK35842 – external advice – women – veil / purdah – marriage Background Please seek advice from ANU’s Dr Shakira Hussein on issues relating to the wearing of the veil and marriage. Questions 1 Please advise if in some cities the hijab and burqa is not commonly worn, such as Islamabad or Lahore or Karachi and whether women in those cities face any difficulties as a result. 2 Please advise if there are any laws regarding the wearing of the hijab or burqu. 3 Please advise whether the police protect women against harassment, by others and by their own family, who chose not to wear the hijab and burqua. 4 Please advise whether marriage between persons from different ethnic groups (eg: Pashtun, Punjabi, Mohajir, Sindhi, Baluchi, etc) are common and how a family might react to such a marriage. External advice On 2 December 2009 the Country Advice Service conducted an interview by telephone with Dr Shakira Hussein. Dr Hussein has appeared as a commentator on issues relating to Muslim women and veiling on a number of panels in recent years1; having undertaken field work in both Pakistan and Afghanistan as part of her recently completed doctoral dissertation on encounters between Muslim and western women.2 Dr Hussein is currently a visiting fellow at the Australian National University.3 The text below has been authorised by Dr Hussein as a 1 For examples, see: ‘The politics of the hijab’ 2009, Unleashed, ABC News, 21 April http://www.abc.net.au/unleashed/stories/s2548643.htm – Accessed 9 December 2009 – Attachment 1; ‘Should We Ban the Burka?; 2009, Australian National University website, 15 July http://www.anu.edu.au/discoveranu/content/podcasts/should_we_ban_the_burka/ – Accessed 9 December 2009 – Attachment 2; ‘Why is there fear and friction between Muslims and non-Muslims?’ 2007, Difference of Opinion, ABC News, 2 April http://www.abc.net.au/tv/differenceofopinion/content/2007/s1887181.htm – Accessed 9 December 2009 – Attachment 3. -

How Headscarves Have Shaped Muslim Experience in America

How Headscarves Have Shaped Muslim Experience in America The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Ghassemi, Arash. 2018. How Headscarves Have Shaped Muslim Experience in America. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42004010 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA How Headscarves Have Shaped Muslim Experience in America Arash Ghassemi A Thesis in the Field of International Relations for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts Harvard University May 2018 © 2018 Arash Ghassemi Abstract This study focuses first on the role of the headscarf in creating space for Muslim women in the social fabric of America and shaping their American experience. I examine the symbolism of the headscarf from two different perspectives: 1. In the first, the headscarf symbolizes a Muslim woman’s identity by embodying the concepts of “Islamic feminism” and “Islamic activism,” both of which involve covered one’s hair as a sign of modesty. Some Muslim women view the headscarf as denoting backwardness, believing that it oppresses women, and they choose not to wear a headscarf. For others, the headscarf is regarded as symbolizing a Muslim woman’s aspirations for modernity and liberation. 2. The second perspective focuses on the symbolism of the headscarf when worn by a Black Muslim-American woman, in particular those who are active in Nation of Islam. -

Religion in the Public Sphere

Religion in the Public Sphere Ars Disputandi Supplement Series Volume 5 edited by MAARTEN WISSE MARCEL SAROT MICHAEL SCOTT NIEK BRUNSVELD Ars Disputandi [http://www.ArsDisputandi.org] (2011) Religion in the Public Sphere Proceedings of the 2010 Conference of the European Society for Philosophy of Religion edited by NIEK BRUNSVELD & ROGER TRIGG Utrecht University & University of Oxford Utrecht: Ars Disputandi, 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Ars Disputandi, version: September 14, 2011 Published by Ars Disputandi: The Online Journal for Philosophy of Religion, [http://www.arsdisputandi.org], hosted by Igitur publishing, Utrecht University Library, The Netherlands [http://www.uu.nl/university/library/nl/igitur/]. Typeset in Constantia 9/12pt. ISBN: 978-90-6701-000-9 ISSN: 1566–5399 NUR: 705 Reproduction of this (or parts of this) publication is permitted for non-commercial use, provided that appropriate reference is made to the author and the origin of the material. Commercial reproduction of (parts of) it is only permitted after prior permission by the publisher. Contents Introduction 1 ROGER TRIGG 1 Does Forgiveness Violate Justice? 9 NICHOLAS WOLTERSTORFF Section I: Religion and Law 2 Religion and the Legal Sphere 33 MICHAEL MOXTER 3 Religion and Law: Response to Michael Moxter 57 STEPHEN R.L. CLARK Section II: Blasphemy and Offence 4 On Blasphemy: An Analysis 75 HENK VROOM 5 Blasphemy, Offence, and Hate Speech: Response to Henk Vroom 95 ODDBJØRN LEIRVIK Section III: Religious Freedom 6 Freedom of Religion 109 ROGER TRIGG 7 Freedom of Religion as the Foundation of Freedom and as the Basis of Human Rights: Response to Roger Trigg 125 ELISABETH GRÄB-SCHMIDT Section IV: Multiculturalism and Pluralism in Secular Society 8 Multiculturalism and Pluralism in Secular Society: Individual or Collective Rights? 147 ANNE SOFIE ROALD 9 After Multiculturalism: Response to Anne Sofie Roald 165 THEO W.A. -

An Embellishment: Purdah

An Embellishment: Purdah For An Embellishment: Purdah,i a two-part text installation for an exhibition, Spatial Imagination (2006), I selected twelve short extracts from ‘To Miss the Desert’ and rewrote them as ‘scenes’ of equal length, laid out in the catalogue as a grid, three squares wide by four high, to match the twelve panes of glass in the west-facing window of the gallery looking onto the street. Here, across the glass, I repeatedly wrote the word ‘purdah’ in black kohl in the script of Afghanistan’s official languages – Dari and Pashto.ii The term purdah means curtain in Persian and describes the cultural practice of separating and hiding women through clothing and architecture – veils, screens and walls – from the public male gaze. The fabric veil has been compared to its architectural equivalent – the mashrabiyya – an ornate wooden screen and feature of traditional North African domestic architecture, which also ‘demarcates the line between public and private space’.iii The origins of purdah, culturally, religiously and geographically, are highly debated,iv and connected to class as well as gender.v The current manifestation of this gendered spatial practice varies according to location and involves covering different combinations of hair, face, eyes and body. In Afghanistan, for example, under the Taliban, when in public, women were required to wear what has been termed a burqa, a word of Pakistani origin. In Afghanistan the full-length veil is more commonly known as the chadoree or chadari, a variation of the Persian chador, meaning tent.vi This loose garment, usually sky-blue, covers the body from head to foot. -

Colonial and Orientalist Veils

Colonial and Orientalist Veils: Associations of Islamic Female Dress in the French and Moroccan Press and Politics Loubna Bijdiguen Goldmiths College – University of London Thesis Submitted for a PhD in Media and Communications Abstract The veiled Muslimah or Muslim woman has figured as a threat in media during the past few years, especially with the increasing visibility of religious practices in both Muslim-majority and Muslim-minority contexts. Islamic dress has further become a means and technique of constructing ideas about the ‘other’. My study explores how the veil comes to embody this otherness in the contemporary print media and politics. It is an attempt to question constructions of the veil by showing how they repeat older colonial and Orientalist histories. I compare and contrast representations of the dress in Morocco and France. This research is about how Muslimat, and more particularly their Islamic attire, is portrayed in the contemporary print media and politics. My research aims to explore constructions of the dress in the contemporary Moroccan and French press and politics, and how the veil comes to acquire meanings, or veil associations, over time. I consider the veil in Orientalist, postcolonial, Muslim and Islamic feminist contexts, and constructions of the veil in Orientalist and Arab Nahda texts. I also examine Islamic dress in contemporary Moroccan and French print media and politics. While I focus on similarities and continuities, I also highlight differences in constructions of the veil. My study establishes the importance of merging and comparing histories, social contexts and geographies, and offers an opportunity to read the veil from a multivocal, multilingual, cross-historical perspective, in order to reconsider discourses of Islamic dress past and present in comparative perspective. -

The Portrayal of the Historical Muslim Female on Screen

THE PORTRAYAL OF THE HISTORICAL MUSLIM FEMALE ON SCREEN A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2017 SABINA SHAH SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES AND CULTURES LIST OF CONTENTS List of Photographs................................................................................................................ 5 List of Diagrams...................................................................................................................... 7 List of Abbreviations.............................................................................................................. 8 Glossary................................................................................................................................... 9 Abstract.................................................................................................................................... 12 Declaration.............................................................................................................................. 13 Copyright Statement.............................................................................................................. 14 Acknowledgements................................................................................................................ 15 Dedication............................................................................................................................... 16 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................