Multimedia Reviews.8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Romancing race and gender : intermarriage and the making of a 'modern subjectivity' in colonial Korea, 1910-1945 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9qf7j1gq Author Kim, Su Yun Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Romancing Race and Gender: Intermarriage and the Making of a ‘Modern Subjectivity’ in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Su Yun Kim Committee in charge: Professor Lisa Yoneyama, Chair Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Jin-kyung Lee Professor Lisa Lowe Professor Yingjin Zhang 2009 Copyright Su Yun Kim, 2009 All rights reserved The Dissertation of Su Yun Kim is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………...……… iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………... iv List of Figures ……………………………………………….……………………...……. v List of Tables …………………………………….……………….………………...…... vi Preface …………………………………………….…………………………..……….. vii Acknowledgements …………………………….……………………………..………. viii Vita ………………………………………..……………………………………….……. xi Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………. xii INTRODUCTION: Coupling Colonizer and Colonized……………….………….…….. 1 CHAPTER 1: Promotion of -

Vs. PETER PARK E

0 0 4 1 1 $3.99 RATED LGY#805 US 4 7 5 9 6 0 6 0 8 9 3 6 9 T BONUS DIGITAL EDITION – DETAILS INSIDE! SPENCER •OTTLEYSPENCER •RATHBURN •MARTIN v s . P E T E R P A R K E R ? ! ? ! PETER PARKER was bitten by a radioactive spider and gained the proportional speed, strength and agility of a SPIDER, adhesive fingertips and toes, and the unique precognitive awareness of danger called “SPIDER-SENSE”! After the tragic death of his Uncle Ben, Peter understood that with great power there must also come great responsibility. He became the crimefighting super hero called… BACK TO BASICS Part Four Remember that radioactive spider we mentioned? At the top of this page? Well, the Isotope Genome Accelerator made it that way. And Peter just got caught in an experiment designed to reverse engineer its capabilities, and was split in two! One mild-mannered civilian, Peter, and one fast- talking super hero, Spider-Man! Initially, both were excited--Peter could have a normal life without endangering his loved ones, and Spider-Man could fight and tame the Tri-Sentinel (for example). But Dr. Connors--the experiment’s designer--and Peter have come come to realize the Isotope Genome Accelerator divides personality traits as well as physical attributes. Who is Peter Parker without his wit or love of science? And more importantly, who is Spider-Man without his sense of responsibility? NICK SPENCER | writer RYAN OTTLEY | penciler CLIFF RATHBURN | inker LAURA MARTIN | colorist SPIDER-MAN created by VC’S JOE CARAMAGNA | letterer PETER PANTAZIS and JASEN SMITH | color assistants STAN LEE RYAN OTTLEY and LAURA MARTIN | cover artists and CHRIS SPROUSE, KARL STORY and DAVE McCAIG | FANTASTIC FOUR variant cover artists STEVE DITKO special thanks to ANTONIO RUIZ ANTHONY GAMBINO | designer KATHLEEN WISNESKI | assistant editor NICK LOWE | editor C.B. -

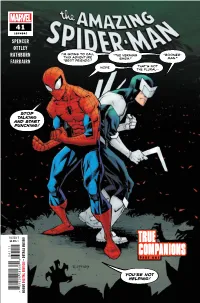

TRUE COMPANIONS Part One

41 LGY#842 SPENCER OTTLEY RATHBURN I’M GOING TO CALL “THE VERMINS “BOOMER- THIS ADVENTURE SAGA.” MAN.” FAIRBAIRN “BEST FRIENDS.” NOPE. THAT’S NOT THE PLURAL-- STOP TALKING AND START PUNCHING! RATED T US TRUE $3.99 1 1 1 4 COMPANIONS 0 PART ONE 9 – DETAILS – INSIDE! 6 3 9 8 0 YOU’RE NOT 6 0 HELPING! 6 DIGITAL EDITION DIGITAL 9 5 7 BONUS BONUS PETER PARKER was bitten by a radioactive spider and gained the proportional speed, strength, and agility of a SPIDER, adhesive fingertips and toes, and the unique precognitive awareness of danger called “SPIDER-SENSE”! After the tragic death of his Uncle Ben, Peter understood that with great power there must also come great responsibility. He became the crimefighting super hero called… TRUE COMPANIONS Part One Spider-Man has tons of problems he would like to fi x, but he’s frequently interrupted by problems he MUST fi x right away. That means there are always three or four fl avors of trouble simmering away while Spidey fi ghts the fi res of the day. Consider the fallout from Kraven the Hunter’s fi nal run at a glorious death: Kraven’s son and Kraven’s half brother, the Chameleon, both want revenge, there are Vermin in the sewers, someone (something?) called Kindred is watching… Then there’re the ongoing facts of Kingpin being mayor, Fred Myers (A.K.A. Boomerang) being one of Peter Parker’s roommates, and the Mayor wanting something from Fred that he absolutely cannot give up… Do you guys smell something burning? NICK SPENCER CLIFF RATHBURN | inker NATHAN FAIRBAIRN | colorist writer VC’s JOE CARAMAGNA | letterer RYAN OTTLEY and NATHAN FAIRBAIRN | cover artists RYAN BROWN [SPIDER-WOMAN] | variant cover artist ANTHONY GAMBINO | designer KATHLEEN WISNESKI | associate editor RYAN OTTLEY NICK LOWE | editor C.B. -

Media/Entertainment Rise of Webtoons Presents Opportunities in Content Providers

Media/Entertainment Rise of webtoons presents opportunities in content providers The rise of webtoons Overweight (Maintain) Webtoons are emerging as a profitable new content format, just as video and music streaming services have in the past. In 2015, webtoons were successfull y monetized in Korea and Japan by NAVER (035420 KS/Buy/TP: W241,000/CP: W166,500) and Kakao Industry Report (035720 KS/Buy/TP: W243,000/CP: W158,000). In late 2018, webtoon user number s April 9, 2020 began to grow in the US and Southeast Asia, following global monetization. This year, NAVER Webtoon’s entry into Europe, combined with growing content consumption due to COVID-19 and the success of several webtoon-based dramas, has led to increasing opportunities for Korean webtoon companies. Based on Google Trends Mirae Asset Daewoo Co., Ltd. data, interest in webtoons is hitting all-time highs across major regions. [Media ] Korea is the global leader in webtoons; Market outlook appears bullish Jeong -yeob Park Korea is the birthplace of webtoons. Over the past two decades, Korea’s webtoon +822 -3774 -1652 industry has created sophisticated platforms and content, making it well-positioned for [email protected] growth in both price and volume. 1) Notably, the domestic webtoon industry adopted a partial monetization model, which is better suited to webtoons than monthly subscriptions and ads and has more upside potent ial in transaction volume. 2) The industry also has a well-established content ecosystem that centers on platforms. We believe average revenue per paying user (ARPPU), which is currently around W3,000, can rise to over W10,000 (similar to that of music and video streaming services) upon full monetization. -

We Are the Walking Dead:” Zombie Spaces, Mobility, and The

“WE ARE THE WALKING DEAD:” ZOMBIE SPACES, MOBILITY, AND THE POTENTIAL FOR SECURITY IN ZONE ONE AND THE WALKING DEAD A RESEARCH PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTERS OF ARTS BY JESSIKA O. GRIFFIN DR. AMIT BAISHYA – ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2012 “We are the walking dead:” Zombified Spaces, Mobility, and the Potential for Security in Zone One and The Walking Dead “I didn’t put you in prison, Evey. I just showed you the bars” (170). —V, V For Vendetta The zombie figure is an indispensible, recurring player in horror fiction and cinema and seems to be consistently revived, particularly in times of political crisis. Film is the best-known medium of zombie consumption in popular culture, and also the most popular forum for academic inquiry relating to zombies. However, this figure has also played an increasingly significant role in written narratives, including novels and comic books. Throughout its relatively short existence, no matter the medium, the zombie has functioned as a mutable, polyvalent metaphor for many of society’s anxieties, with zombie film production spiking during society’s most troublesome times, including times of war, the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and, more recently, 9/11.1 In Shocking Representations, Adam Lowenstein describes the connection between historical events and cinema by first describing how history is experienced collectively. Lowenstein describes historical traumas as “wounds” in the sense that they are painful, but also in that they continue to “bleed through conventional confines of time and space” (1). -

Dead Rising 2 Reviewer's Guide (Low Resolution)

Content Falls In FALL 2010 LET’S GET STARTED Your Letters Editor-In-Chief 4 CAPCOM Letter From The Editor Editorial Director Greg Off 8 Senior Editor KEEPING ENTERTAINED Stacy Burt The Hot List Associate Editor 10 David Brothers Night Time Visitors Assistant Editor 12 Lindsay Young All The Brains You Can Eat Contributing Medical Expert 14 Isabela Keyes Five Ways To Tell If Your Date Director of Photography Is Infected Frank West 16 Senior Designer Timothy Lindquist Wingin’ It Associate Designers 20 Cyrin Jocson, STYLE • LOOKING GOOD Sarah Gilbert, Alvin Domingo Save The World And Look Good National Advertising Director Doing It Brady Hartel 22 Security Does This Make Me Look Dead? Brad Garrison, Jessica McCarney 26 Janitor DIY: Affordable Mayhem Otis Washington 30 Transportation What’s Your Perfect Match? Ed DeLuca A PARTNERSHIP TO BENEFIT DEAD RIGHTS 34 FEATURE PRESENTATION The New Guy In Town 38 Fortune City’s Players 42 “ZQ” is trademark of Capcom. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system without written permission from Capcom. When Time is of the Essence Capcom and the authors have made every effort to ensure Stacey Forsythe and Intercept have joined together to that the information contained in this magazine is accurate. However, the publisher makes no warranty, either expressed contribute to the Unnaturally Dead Defense Council. or implied, as to the accuracy, effectiveness, or completeness of the material in this magazine; nor does the publisher assume liability for damages, either incidental or consequential, « When you need to track your Zombrex intake, only the best time that may result from using the information in this magazine. -

Banda Deseñada Americana

BANDA DESEÑADA AMERICANA BIBLIOTECA MUNICIPAL Saga / guión, Brian K. Vaughan ; dibujo, Fiona Staples ; coordinador, Eric Stephenson Localización: COMIC VAU sag [vermello] La Visión / Tom King, guión ; Gabriel Hernández Walta, Michael Walsh, dibujo y entintado ; Jordie Bellaire, color ; [traducción, Santiago García y Uriel López]. Localización: COMIC KIN vis [vermello] The Wicked + The divine / Kieron Gillen, guión ; Jamie McKelvie, dibujo ; Matthew Wilson, color ; Clayton Cowles, rotulación original Localización: COMIC GIL wic [vermello] Ojo de halcón seis días en la vida de... / Matt Fraction ; portada de David Aja. Localización: COMIC FRA ojo [vermello] Monstress / Marjorie Liu, guión ; Sana Takeda, dibujo Localización: COMIC LIU mon [vermello] Capitán América.1,Otro tiempo / Ed Brubaker, Steve Epting. Localización: COMIC CAP BRU cap [vermello] Batman : el regreso del caballero oscuro / Frank MIller, Klaus Janson, Lynn Varley Localización: COMIC BAT MIL bat [vermello] Spiderman / guión, Stan Lee ; dibujo, Steve Ditko, Jack Kirby. Localización: COMIC SPI LEE spi [vermello] Star Wars : saga completa : episodios I a VI / [traducción, Diego de los Santos ; guión, Henry Gilroy ... et al. ; dibujo, Jan Duursema ... et al.]. Localización: COMIC STA [vermello] Los muertos vivientes / guión, Robert Kirkman ; dibujos, Tony Moore, Charlie Adlard ; tonos grises, Cliff Rathburn. Localización: COMIC KIR mue [vermello] Maus : relato dun supervivente / Art Spiegelman ; [tradución Diego García Cruz]. Localización: COMIC SPI mau [vermello] Watchmen / Alan Moore, guión ; Dave Gibbons, dibujo ; John Higgins, color. Localización: COMIC MOO wat [vermello] Daredevil : born again / [guión, Frank Miller ; dibujo, David Mazzucchelli] Localización: COMIC MIL dar [vermello] La cosa del pantano / Alan Moore, Stephen Bisette, John Totleben ; [traducción, Fran San Rafael]. Localización: COMIC MOO cos [vermello] Hellboy / guión y dibujo, Mike Mignola ; color Dave Stewart ; [traducción, Carles M. -

Sweet Home Alabama's Reese Witherspoon Talks About

COVER 8/9/02 1:56 PM Page x2 canada’s #1 movie magazine in canada’s #1 theatres 3/C B G september 2002 | volume 3 | number 9 R 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 ABANDON’S BENJAMIN BRATT MOVES ON * SPOTLIGHT ON: JAMES FRANCO 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 & KATE HUDSON * FALL FASHION WITH JEANNE BEKER Sweet Home Alabama’s Reese Witherspoon talks about finding success on and off the screen 100 2 5 25 50 75 95 98 $3.00 SALMA HAYEK AND GILLIAN ANDERSON FANTASIZE ABOUT SCREENMATES PL2060_Famous_Reason1.qxd 8/12/02 3:43 PM Page 1 Reason #1: The price. Now only $299* *MSRP. "PlayStation" and the "PS" Family logo are registered trademarks of Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. Horizontal stand not included. 716860-SK 1pg Ad pre-street 8/12/02 11:52 AM Page 1 as this year’s biggest, extreme, non-stop action event. Featuring WWF sensation, “THE ROCK”. The Scorpion King takes you on an extreme adventure featuring mind-blowing action sequences and larger than life battles. You will be fighting to own this intense DVD or Video that continues the epic Mummy series! • Extended Version in Enhanced Viewing Mode VHS A unique opportunity to see alternate versions of key scenes in the movie $ 25.95 DVD • Live Footage from “The Rock’s” Feature Commentary S.R.P. $34.95 • Outtakes and Alternate Versions of Key Scenes S.R.P. • The Fight Scenes The process of shooting a fight sequence • Universal Studios Total Axess Revolutionary DVD-ROM experience that contains exclusive added value and behind-the-scenes footage • Godsmack Music Video “I Stand Alone” CD Soundtrack featuring 3 new “live” songs by multi-platinum artists GODSMACK, plus other hits by: • P.O.D. -

Title of Book/Magazine/Newspaper Author/Issue Datepublisher Information Her Info

TiTle of Book/Magazine/newspaper auThor/issue DaTepuBlisher inforMaTion her info. faciliT Decision DaTe censoreD appealeD uphelD/DenieD appeal DaTe fY # American Curves Winter 2012 magazine LCF censored September 27, 2012 Rifts Game Master Guide Kevin Siembieda book LCF censored June 16, 2014 …and the Truth Shall Set You Free David Icke David Icke book LCF censored October 5, 2018 10 magazine angel's pleasure fluid issue magazine TCF censored May 15, 2017 100 No-Equipment Workout Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 No-Equipment Workouts Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 of the Most Beautiful Women in Painting Ed Rebo book HCF censored February 18, 2011 100 Things You Will Never Find Daniel Smith Quercus book LCF censored October 19, 2018 100 Things You're Not Supposed To Know Russ Kick Hampton Roads book HCF censored June 15, 2018 100 Ways to Win a Ten-Spot Comics Buyers Guide book HCF censored May 30, 2014 1000 Tattoos Carlton Book book EDCF censored March 18, 2015 yes yes 4/7/2015 FY 15-106 1000 Tattoos Ed Henk Schiffmacher book LCF censored December 3, 2007 101 Contradictions in the Bible book HCF censored October 9, 2017 101 Cult Movies Steven Jay Schneider book EDCF censored September 17, 2014 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genius Brad Graham & Kathy McGowan book HCF censored August 31, 2011 yes yes 9/27/2011 FY 12-009 110 Years of Broadway Shows, Stories & Stars: At this Theater Viagas & Botto Applause Theater & Cinema Books book LCF censored November 30, 2018 113 Minutes James Patterson Hachette books book -

Capcom Cheats

Capcom cheats For Marvel vs. Capcom: Clash of Super Heroes on the Arcade Games, GameFAQs has 40 cheat codes and secrets. For Capcom Classics Collection Reloaded on the PSP, GameFAQs has 41 cheat codes and secrets.Kai · The Battle of Midway · Ghosts 'n Goblins · Capcom: Clash of Super Heroes: This page contains a list of cheats, codes, Easter eggs, tips, and other secrets for Marvel vs. Capcom: Clash of. Capcom: Clash of Super Heroes Cheats - PlayStation Cheats: This page contains a list of cheats, codes, Easter eggs, tips, and other secrets for. Play as Lilith. At the character selection screen, highlight Zangief, then press Left(2), Down(2), Right(2), Up(2), Down(4), Left(2), Up(4), Right, Left, Down(4). The best place to get cheats, codes, cheat codes, hints, tips, tricks, and secrets for the PlayStation (PSX). Capcom: Clash Of The Super Heroes EX Edition. Find all our Marvel vs. Capcom Cheats for Arcade. Plus great forums, game help and a special question and answer system. All Free. Asgard: Beat Arcade Mode eight Times Danger Room: Beat Arcade Mode once. Demon Village: Beat Arcade Mode Four Times Fate of the Earth: Beat Arcade. Marvel vs. Capcom Dreamcast Play as Lilith Morrigan: At the Character Selection screen, highlight Zangief and press Left (2), Down (2), Right (2), Up (2), Down. For Capcom Arcade Cabinet on the Xbox , GameRankings has 59 cheat codes and secrets. Cheats, codes, passwords, hints, tips, tricks, help and Easter eggs for the Sega Dreamcast game, Marvel Vs. Capcom: Clash of Super Heroes. The latest Dead Rising: Off The Record DLC pack adds various cheat modes to Capcom's re-tooled zombie sequel. -

Studio Dragon (253450 KS)

Company Report Jan 15, 2021 Studio Dragon (253450 KS) Media/entertainment To continue focusing on webtoon IP in 2021 Webtoon adaptation “Sweet Home” enjoys huge global success In 2020, Studio Dragon produced a total of 28 dramas (captive 24, terrestrial TV 2, Netflix Originals 2). Among these, five dramas were based on webtoon IP (“Memorist,” “Rugal,” “The Uncanny Counter,” “True Beauty,” and “Sweet Home”). Netflix original series “Sweet Home” was co-produced by Naver Webtoon’s subsidiary, Studio N, with Studio Dragon’s Lee Eung-bok as director. It is a blockbuster drama that cost W30bn (W3bn per episode) to make. Sweet Home was launched on Netflix on Dec 18, 2020, and was the third-ranked show on Netflix in the 52nd week of 2020. This is the best ever performance by a Korean drama on Netflix, which we attribute to the overseas Rating BUY (M) popularity of the original webtoon on Naver Webtoon, coupled with unique elements and an engaging story. Production of Sweet Home season 2 has yet to be decided, but Target price W115,000 (M) expectations for additional seasons are high given the huge popularity of the first season. Current price (Jan 4) W94,500 Enhanced cooperation with Naver Upside potential 22% Naver acquired a 6.3% stake in Studio Dragon through a share swap deal with CJ Corp affiliates in Oct~Nov 2020, while Studio Dragon acquired a 0.3% stake in Naver. The share Market cap (Wbn) 2,835 swap between two will likely lead to: 1) increased premium content production of Naver Shares outstanding 30,004,345 Webtoon’s IP; 2) digital content production; and 3) cooperation in production and distribution Avg daily T/O (2M, Wbn) 21 of global dramas. -

A Visual Semiotic Analysis on Webtoon Sweet Home

A VISUAL SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS ON WEBTOON SWEET HOME THESIS BY PUJA INDRIANA NASUTION NO. REG. 170705035 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATRA UTARA MEDAN 2021 i ii iii iv AUTHOR'S DECLARATION I, PUJA INDRIANA NASUTION DECLARE THAT I AM TIHIE SOLE AUTHOR OF THIS THESIS EXCEPT WHERE REFERENCE IS MADE IN THE TEXT OF HIS THESIS, THIS THESIS CONTAINS NO MATERIAL PUBLISHED ELSEWHERE OR EXTRACTED IN WHOLE OR IN PART FROM A THESIS BY WHICH I HAVE QUALIFIED FOR OR AWARDED ANOTHER DEGREE. NO OTHER PERSON'S WORK HAS BEEN USED WITHOUT DUE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IN THE MAIN TEXT OF THIS THESIS. THIS THESIS HAS NOT BEEN SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF ANOTHER DEGREE IN ANY TERTIARY EDUCATION. Signed : Date : Mei 05th’ 2021 v COPYRIGHT DECLARATION NAME : PUJA INDRIANA NASUTION TITLE OF THESIS : A VISUAL SEMIOTICS ANALYSIS ON WEBTOON SWEET HOME QUALIFICATION :SI/SARJANA SASTRA DEPARTMENT : ENGLISH I AM WILLING THAT MY THESIS SHOULD BE AVAILABLE FOR REPRODUCTION AT DISCREATION OF THE LIBRARIAN OF DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH, FACULTY OF CULTURAL SCIENCES, UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA ON THE UNDERSTANDING THAT USERS ARE MADE AWARE OF THEIR OBLIGATION UNDER THE LAW OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA. Signed : Date : Mei 05th, 2021 vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It was such a long journey but a rewarding experience to work on this thesis. This thesis will be impossible without the support of many people. First of all, I would like to thank to Allah Subhanahu wa ta‟ala for his blessing and for giving me health, strength in the process of accomplishing this paper.