Power to Protest Presidencies? Lessons Learned from the Successful Mobilization and Diverging Effects of Popular Uprisings in Senegal and Burkina Faso

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons from Burkina Faso's Thomas Sankara By

Pan-Africanism and African Renaissance in Contemporary Africa: Lessons from Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara By: Moorosi Leshoele (45775389) Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: Prof Vusi Gumede (September 2019) DECLARATION (Signed) i | P a g e DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to Thomas Noel Isadore Sankara himself, one of the most underrated leaders in Africa and the world at large, who undoubtedly stands shoulder to shoulder with ANY leader in the world, and tall amongst all of the highly revered and celebrated revolutionaries in modern history. I also dedicate this to Mariam Sankara, Thomas Sankara’s wife, for not giving up on the long and hard fight of ensuring that justice is served for Sankara’s death, and that those who were responsible, directly or indirectly, are brought to book. I also would like to tremendously thank and dedicate this thesis to Blandine Sankara and Valintin Sankara for affording me the time to talk to them at Sankara’s modest house in Ouagadougou, and for sharing those heart-warming and painful memories of Sankara with me. For that, I say, Merci boucop. Lastly, I dedicate this to my late father, ntate Pule Leshoele and my mother, Mme Malimpho Leshoele, for their enduring sacrifices for us, their children. ii | P a g e AKNOWLEDGEMENTS To begin with, my sincere gratitude goes to my Supervisor, Professor Vusi Gumede, for cunningly nudging me to enrol for doctoral studies at the time when the thought was not even in my radar. -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

RCS Demographics V2.0 Codebook

Religious Characteristics of States Dataset Project Demographics, version 2.0 (RCS-Dem 2.0) CODE BOOK Davis Brown Non-Resident Fellow Baylor University Institute for Studies of Religion [email protected] Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following persons for their assistance, without which this project could not have been completed. First and foremost, my co-principal investigator, Patrick James. Among faculty and researchers, I thank Brian Bergstrom, Peter W. Brierley, Peter Crossing, Abe Gootzeit, Todd Johnson, Barry Sang, and Sanford Silverburg. I also thank the library staffs of the following institutions: Assembly of God Theological Seminary, Catawba College, Maryville University of St. Louis, St. Louis Community College System, St. Louis Public Library, University of Southern California, United States Air Force Academy, University of Virginia, and Washington University in St. Louis. Last but definitely not least, I thank the following research assistants: Nolan Anderson, Daniel Badock, Rebekah Bates, Matt Breda, Walker Brown, Marie Cormier, George Duarte, Dave Ebner, Eboni “Nola” Haynes, Thomas Herring, and Brian Knafou. - 1 - TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Citation 3 Updates 3 Territorial and Temporal Coverage 4 Regional Coverage 4 Religions Covered 4 Majority and Supermajority Religions 6 Table of Variables 7 Sources, Methods, and Documentation 22 Appendix A: Territorial Coverage by Country 26 Double-Counted Countries 61 Appendix B: Territorial Coverage by UN Region 62 Appendix C: Taxonomy of Religions 67 References 74 - 2 - Introduction The Religious Characteristics of States Dataset (RCS) was created to fulfill the unmet need for a dataset on the religious dimensions of countries of the world, with the state-year as the unit of observation. -

Mise En Page 1

[]Annual Report 2004 Legalmentions Published by : IUCN Regional Office for West Africa, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso © 2005 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowled- ged. Citation : IUCN-BRAO (2005). Annual Report 2004, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. 34 pp. ISBN : 2-8317-0851-6 Cover photos : J.F. Hellion N. Van Ingen - FIBA IUCN Jean-Marc GARREAU Louis Gérard d’ESCRIENNE Design and layout by : DIGIT’ART Printed by : Ghana Printing & Packaging Industries LTD Available from : IUCN-regional office for West Africa 01 BP 1618 Ouagadougou 01 Burkina Faso Tél.: (226) 50 32 85 00 Fax : (226) 50 30 75 61 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.iucn.org/brao IUCN []3 []Annual Report 2004 Contents 6 Foreword Substantial Development of the Regional Programme in 2004 8 IUCN donors A Standing Support 10 Four Years in West Africa 10 - Introduction 12 - The Regional Wetlands Programme 15 - Economic and Social Equity as Core Principle of Conservation 18 - Creating Dialogue for Influencing Policies 21 - WAP transboundary Complex Protecting the Environment is “ to guarantee social and economic livelihood 24 West Africa at the Bangkok Congress IUCN-BRAO took part in the Bangkok World Conservation Congress “ of populations in West Africa 26 Programme Development prospects for IUCN West Africa 26 - The New Four-Year Programme 31 - The PRCM is moving forward 32 Annexes 32 - Financial Reports 33 - Recent Publications 33 - List of IUCN Members in West Africa 34 - IUCN Offices []4 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR WEST AFRICA IUCN []5 []Annual Report 2004 West Africa Members, up to date with the Foreword bylaws of the Organisation, were all represented at this meeting. -

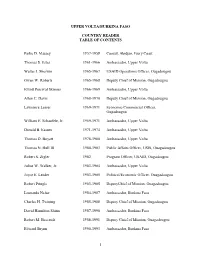

Upper Volta/Burkina Faso Country Reader Table Of

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast homas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper (olta )alter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID ,perations ,ffi.er, ,ugadougou ,wen ). 0oberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,ugadougou Elliott Per.ival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper (olta Allen C. Davis 1968-1971 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,ugadougou 2awren.e 2esser 1969-1971 E.onomi.3Commer.ial ,ffi.er, ,ugadougou )illiam E. S.haufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper (olta Donald 4. Easum 1971-1975 Ambassador, Upper (olta homas D. 4oyatt 1978-1981 Ambassador, Upper (olta 0obert S. 6igler 1982 Program ,ffi.er, USAID, ,ugadougou Julius ). )alker, Jr. 1988-1985 Ambassador, Upper (olta Joy.e E. 2eader 1988-1985 Politi.al3E.onomi. ,ffi.er, ,uagadougou 2eonardo Neher 1985-1987 Ambassador, 4urkina :aso Charles H. wining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,ugadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1991 Ambassador, 4urkina :aso 0obert M. 4ee.rodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,uagadougou Edward 4rynn 1991-1998 Ambassador, 4urkina :aso PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidj n, Ivory Co st (1957-195,- Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford Co ege with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He a so served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Me-ico City, .enoa, Abid/an, and .ermany. 0hi e in USA1D, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bo ivia, Chi e, Haiti, and Uruguay. -

Senegal#.Vxcptt2rt8e.Cleanprint

https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2015/senegal#.VXCptt2rT8E.cleanprint Senegal freedomhouse.org Municipal elections held in June 2014 led to some losses by ruling coalition candidates in major urban areas; the elections were deemed free and fair by local election observers. A trial against Karim Wade, son of former president Abdoulaye Wade, began in July in the Court of Repossession of Illegally Acquired Assets (CREI), where he is accused of illicit enrichment. Abdoulaye Wade, who had left Senegal after losing the 2012 presidential election, returned in the midst of the CREI investigation in April. The Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS), which he founded in 1974, requested permission to publicly assemble upon his return, but authorities denied the request. In February, Senegal drew criticism for the imprisonment of two men reported to have engaged in same-sex relations. The detentions of rapper and activist Malal Talla and of former energy minister Samuel Sarr in June and August, respectively, also evoked public disapproval; both men were detained after expressing criticism of government officials. Political Rights and Civil Liberties: Political Rights: 33 / 40 [Key] A. Electoral Process: 11 / 12 Members of Senegal’s 150-seat National Assembly are elected to five-year terms; the president serves seven-year terms with a two-term limit. The president appoints the prime minister. In July 2014, President Macky Sall appointed Mohammed Dionne to this post to replace Aminata Touré, who was removed from power after losing a June local election in Grand-Yoff. The National Commission for the Reform of Institutions (CNRI), an outgrowth of a consultative body that engaged citizens about reforms in 2008–2009, presented a new draft constitution to Sall in February. -

Research Master Thesis

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose? Understanding how and why new ICTs played a role in Burkina Faso’s recent journey to socio-political change Fiona Dragstra, M.Sc. Research Master Thesis Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose? Understanding how and why new ICTs played a role in Burkina Faso’s recent journey to socio-political change Research Master Thesis By: Fiona Dragstra Research Master African Studies s1454862 African Studies Centre, Leiden Supervisors: Prof. dr. Mirjam de Bruijn, Leiden University, Faculty of History dr. Meike de Goede, Leiden University, Faculty of History Third reader: dr. Sabine Luning, Leiden University, Faculty of Social Sciences Date: 14 December 2016 Word count (including footnotes): 38.339 Cover photo: Young woman protests against the coup d’état in Bobo-Dioulasso, September 2015. Photo credit: Lefaso.net and @ful226, Twitter, 20 September 2015 All pictures and quotes in this thesis are taken with and used with consent of authors and/or people on pictures 1 A dedication to activists – the Burkinabè in particular every protest. every voice. every sound. we have made. in the protection of our existence. has shaken the entire universe. it is trembling. Nayyirah Waheed – a poem from her debut Salt Acknowledgements Together we accomplish more than we could ever do alone. My fieldwork and time of writing would have never been as successful, fruitful and wonderful without the help of many. First and foremost I would like to thank everyone in Burkina Faso who discussed with me, put up with me and helped me navigate through a complex political period in which I demanded attention and precious time, which many people gave without wanting anything in return. -

Senegal: Presidential Elections 2019 - the Shining Example of Democratic Transition Immersed in Muddy Power-Politics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Munich Personal RePEc Archive MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive Senegal: Presidential elections 2019 - The shining example of democratic transition immersed in muddy power-politics Dirk Kohnert and Laurence Marfaing Institute of African Affairs, GIGA-Hamburg 12 March 2019 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/92739/ MPRA Paper No. 92739, posted 15 March 2019 17:14 UTC Senegal: Presidential elections 2019 The shining example of democratic transition immersed in muddy power-politics Dirk Kohnert & Laurence Marfaing 1 The rush of presidential candidates to the religious leaders Source: Landry Banga (nom de plume, RIC). Dakar: La Croix Africa, 19 February 2019 Abstract: Whereas Senegal has long been sold as a showcase of democracy in Africa, including peaceful political alternance, things apparently changed fundamentally with the Senegalese presidentials of 2019 that brought new configurations. One of the major issues was political transhumance that has been elevated to the rank of religion in defiance of morality. It threatened political stability and peace. In response, social networks of predominantly young activists, created in 2011 in the aftermath of the Arab Spring focused on grass-roots advocacy with the electorate on good governance and democracy. They proposed a break with a political system that they consider as neo- colonialist. Moreover, Senegal’s justice is frequently accused to be biased, and the servility of the Constitutional Council which is in the first place an electoral court has often been denounced. Key Words: Senegal, presidential elections, governance, political change, political transhumance, social networks, West Africa, WAEMU, ECOWAS, civic agency JEL-Code: N17, N37, N97, O17, O35, P16, Z13 1 Associated research fellows at the Institute of African Affairs, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg, Germany. -

Table of Contents

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast Thomas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper Volta Walter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID Operations Officer, Ougadougou Owen W. Roberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Elliott Percival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper Volta Allen C. Davis 1968-1970 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Lawrence Lesser 1969-1971 Economic/Commercial Officer, Ougadougou William E. Schaufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper Volta Donald B. Easum 1971-1974 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas D. Boyatt 1978-1980 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas N. Hull III 1980-1983 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Ouagadougou Robert S. Zigler 1982 Program Officer, USAID, Ougadougou Julius W. Walker, Jr. 1983-1984 Ambassador, Upper Volta Joyce E. Leader 1983-1985 Political/Economic Officer, Ouagadougou Robert Pringle 1983-1985 DeputyChief of Mission, Ouagadougou Leonardo Neher 1984-1987 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Charles H. Twining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1990 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Robert M. Beecrodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ouagadougou Edward Brynn 1990-1993 Ambassador, Burkina Faso 1 PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidjan, Ivory Coast (1957-1958) Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford College with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He also served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Mexico City, Genoa, Abidjan, and Germany. While in USAID, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bolivia, Chile, Haiti, and Uruguay. -

On the Trail N°26

The defaunation bulletin Quarterly information and analysis report on animal poaching and smuggling n°26. Events from the 1st July to the 30th September, 2019 Published on April 30, 2020 Original version in French 1 On the Trail n°26. Robin des Bois Carried out by Robin des Bois (Robin Hood) with the support of the Brigitte Bardot Foundation, the Franz Weber Foundation and of the Ministry of Ecological and Solidarity Transition, France reconnue d’utilité publique 28, rue Vineuse - 75116 Paris Tél : 01 45 05 14 60 www.fondationbrigittebardot.fr “On the Trail“, the defaunation magazine, aims to get out of the drip of daily news to draw up every three months an organized and analyzed survey of poaching, smuggling and worldwide market of animal species protected by national laws and international conventions. “ On the Trail “ highlights the new weapons of plunderers, the new modus operandi of smugglers, rumours intended to attract humans consumers of animals and their by-products.“ On the Trail “ gathers and disseminates feedback from institutions, individuals and NGOs that fight against poaching and smuggling. End to end, the “ On the Trail “ are the biological, social, ethnological, police, customs, legal and financial chronicle of poaching and other conflicts between humanity and animality. Previous issues in English http://www.robindesbois.org/en/a-la-trace-bulletin-dinformation-et-danalyses-sur-le-braconnage-et-la-contrebande/ Previous issues in French http://www.robindesbois.org/a-la-trace-bulletin-dinformation-et-danalyses-sur-le-braconnage-et-la-contrebande/ -

23 3 Kelly.Pdf

Access Provided by Harvard University at 07/13/12 4:30PM GMT Senegal: What Will turnover Bring? Catherine Lena Kelly Catherine Lena Kelly is a doctoral candidate in government at Har- vard University. She is writing a dissertation on the formation, co- alition-building strategies, and durability of political parties in sub- Saharan Africa, and has spent fifteen months in Senegal. On 25 March 2012, Macky Sall of the Alliance for the Republic (APR) won the second round of Senegal’s presidential election with 65.8 per- cent of the vote, handily defeating incumbent president Abdoulaye Wade of the Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS), who had won the most votes in the first round. In contrast to a tumultuous campaign season, elec- tion day itself was relatively peaceful. Wade graciously accepted defeat, phoning Sall to congratulate him several hours after the polls closed. French president Nicolas Sarkozy called this gesture “proof of [Wade’s] attachment to democracy.”1 This appraisal is too generous, however. The peaceful turnover followed months of protests and violent repres- sion, as well as a rumored intervention by military officials to force Wade to accept defeat after the second-round voting. 2 Debates about the constitutionality of Wade’s candidacy, as well as an earlier change that he had proposed in the election law, helped to generate this turmoil, which included at least ten deaths, dozens of arrests, and many injuries. 3 Wade’s quest for a third term belied Senegal’s democratic reputation. In fact, the country’s regime would be better described as competitive authoritarian—democratic rules exist, but “incumbents violate those rules so often and to such an extent . -

Sub-Saharan Afr I CA

/ sUB-sAhArAN AFrICA observatory for the protection of human rights defenders annual report 2009 …17 / regIoNAl ANALYSIs sUB-sAhArAN AFrICA observatory for the protection of human rights defenders annual report 2009 Thanks to the dissemination, the awareness and the appropriation of the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Defenders by the African human rights mechanisms, the issue of human rights defenders is now more visible on the African continent, to which the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights (ACHPR) has largely contributed. The issue however is still not one to which the integrated institutions of the African Union – such as the High Authority, the Peace and Security Council or the Conference of the Heads of State and Government – are particularly sensitive. The inclusion of the issue in the work programmes of these bodies, the access of defenders to their various meetings and the activation of the future African Court of Human and People’s Rights for the protection of human rights defenders will therefore be the challenges to be faced in the years to come. While some African States have for some years tolerated the freedom of expression of human rights defenders (Burkina Faso, Mali, Togo, Zambia), others on the contrary have remained completely opposed to any independent examination of the human rights situation, as is the case, for example, of Eritrea or Equatorial Guinea. In Gambia, owing to the systematic violations of human rights, African and international NGOs have for several years been campaigning for ACPHR headquar- ters to be transferred to a country more respectful of human rights.