Species Profile: Quercus Palmeri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malosma Laurina (Nutt.) Nutt. Ex Abrams

I. SPECIES Malosma laurina (Nutt.) Nutt. ex Abrams NRCS CODE: Family: Anacardiaceae MALA6 Subfamily: Anacardiodeae Order: Sapindales Subclass: Rosidae Class: Magnoliopsida Immature fruits are green to red in mid-summer. Plants tend to flower in May to June. A. Subspecific taxa none B. Synonyms Rhus laurina Nutt. (USDA PLANTS 2017) C. Common name laurel sumac (McMinn 1939, Calflora 2016) There is only one species of Malosma. Phylogenetic analyses based on molecular data and a combination of D. Taxonomic relationships molecular and structural data place Malosma as distinct but related to both Toxicodendron and Rhus (Miller et al. 2001, Yi et al. 2004, Andrés-Hernández et al. 2014). E. Related taxa in region Rhus ovata and Rhus integrifolia may be the closest relatives and laurel sumac co-occurs with both species. Very early, Malosma was separated out of the genus Rhus in part because it has smaller fruits and lacks the following traits possessed by all species of Rhus : red-glandular hairs on the fruits and axis of the inflorescence, hairs on sepal margins, and glands on the leaf blades (Barkley 1937, Andrés-Hernández et al. 2014). F. Taxonomic issues none G. Other The name Malosma refers to the strong odor of the plant (Miller & Wilken 2017). The odor of the crushed leaves has been described as apple-like, but some think the smell is more like bitter almonds (Allen & Roberts 2013). The leaves are similar to those of the laurel tree and many others in family Lauraceae, hence the specific epithet "laurina." Montgomery & Cheo (1971) found time to ignition for dried leaf blades of laurel sumac to be intermediate and similar to scrub oak, Prunus ilicifolia, and Rhamnus crocea; faster than Heteromeles arbutifolia, Arctostaphylos densiflora, and Rhus ovata; and slower than Salvia mellifera. -

Lake Harney Wilderness Area Land Management Plan

Lake Harney Wilderness Area Land Management Plan 2010 LAKE HARNEY WILDERNESS AREA LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 WILDERNESS AREA OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................................. 1 REGIONAL SIGNIFICANCE .................................................................................................................................................. 1 ACQUISITION HISTORY ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 NATURAL RESOURCES OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................... 4 NATURAL COMMUNITIES.................................................................................................................................................. 4 FIRE ............................................................................................................................................................................. 5 WILDLIFE ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 EXOTICS ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

The Collection of Oak Trees of Mexico and Central America in Iturraran Botanical Gardens

The Collection of Oak Trees of Mexico and Central America in Iturraran Botanical Gardens Francisco Garin Garcia Iturraran Botanical Gardens, northern Spain [email protected] Overview Iturraran Botanical Gardens occupy 25 hectares of the northern area of Spain’s Pagoeta Natural Park. They extend along the slopes of the Iturraran hill upon the former hay meadows belonging to the farmhouse of the same name, currently the Reception Centre of the Park. The minimum altitude is 130 m above sea level, and the maximum is 220 m. Within its bounds there are indigenous wooded copses of Quercus robur and other non-coniferous species. Annual precipitation ranges from 140 to 160 cm/year. The maximum temperatures can reach 30º C on some days of summer and even during periods of southern winds on isolated days from October to March; the winter minimums fall to -3º C or -5 º C, occasionally registering as low as -7º C. Frosty days are few and they do not last long. It may snow several days each year. Soils are fairly shallow, with a calcareous substratum, but acidified by the abundant rainfall. In general, the pH is neutral due to their action. Collections The first plantations date back to late 1987. There are currently approximately 5,000 different taxa, the majority being trees and shrubs. There are around 3,000 species, including around 300 species from the genus Quercus; 100 of them are from Mexico and Central America. Quercus costaricensis photo©Francisco Garcia 48 International Oak Journal No. 22 Spring 2011 Oaks from Mexico and Oaks from Mexico -

Native Trees of Georgia

1 NATIVE TREES OF GEORGIA By G. Norman Bishop Professor of Forestry George Foster Peabody School of Forestry University of Georgia Currently Named Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources University of Georgia GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION Eleventh Printing - 2001 Revised Edition 2 FOREWARD This manual has been prepared in an effort to give to those interested in the trees of Georgia a means by which they may gain a more intimate knowledge of the tree species. Of about 250 species native to the state, only 92 are described here. These were chosen for their commercial importance, distribution over the state or because of some unusual characteristic. Since the manual is intended primarily for the use of the layman, technical terms have been omitted wherever possible; however, the scientific names of the trees and the families to which they belong, have been included. It might be explained that the species are grouped by families, the name of each occurring at the top of the page over the name of the first member of that family. Also, there is included in the text, a subdivision entitled KEY CHARACTERISTICS, the purpose of which is to give the reader, all in one group, the most outstanding features whereby he may more easily recognize the tree. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers of Sargent’s Manual of the Trees of North America, for permission to use the cuts of all trees appearing in this manual; to B. R. Stogsdill for assistance in arranging the material; to W. -

Synteny Analysis in Rosids with a Walnut Physical Map Reveals Slow Genome Evolution in Long-Lived Woody Perennials Ming-Cheng Luo1, Frank M

Luo et al. BMC Genomics (2015) 16:707 DOI 10.1186/s12864-015-1906-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Synteny analysis in Rosids with a walnut physical map reveals slow genome evolution in long-lived woody perennials Ming-Cheng Luo1, Frank M. You2, Pingchuan Li2, Ji-Rui Wang1,4, Tingting Zhu1, Abhaya M. Dandekar1, Charles A. Leslie1, Mallikarjuna Aradhya3, Patrick E. McGuire1 and Jan Dvorak1* Abstract Background: Mutations often accompany DNA replication. Since there may be fewer cell cycles per year in the germlines of long-lived than short-lived angiosperms, the genomes of long-lived angiosperms may be diverging more slowly than those of short-lived angiosperms. Here we test this hypothesis. Results: We first constructed a genetic map for walnut, a woody perennial. All linkage groups were short, and recombination rates were greatly reduced in the centromeric regions. We then used the genetic map to construct a walnut bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone-based physical map, which contained 15,203 exonic BAC-end sequences, and quantified with it synteny between the walnut genome and genomes of three long-lived woody perennials, Vitis vinifera, Populus trichocarpa,andMalus domestica, and three short-lived herbs, Cucumis sativus, Medicago truncatula, and Fragaria vesca. Each measure of synteny we used showed that the genomes of woody perennials were less diverged from the walnut genome than those of herbs. We also estimated the nucleotide substitution rate at silent codon positions in the walnut lineage. It was one-fifth and one-sixth of published nucleotide substitution rates in the Medicago and Arabidopsis lineages, respectively. We uncovered a whole-genome duplication in the walnut lineage, dated it to the neighborhood of the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary, and allocated the 16 walnut chromosomes into eight homoeologous pairs. -

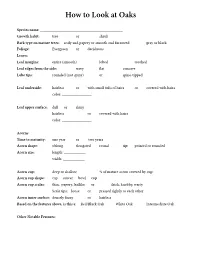

How to Look at Oaks

How to Look at Oaks Species name: __________________________________________ Growth habit: tree or shrub Bark type on mature trees: scaly and papery or smooth and furrowed gray or black Foliage: Evergreen or deciduous Leaves Leaf margins: entire (smooth) lobed toothed Leaf edges from the side: wavy fat concave Lobe tips: rounded (not spiny) or spine-tipped Leaf underside: hairless or with small tufs of hairs or covered with hairs color: _______________ Leaf upper surface: dull or shiny hairless or covered with hairs color: _______________ Acorns Time to maturity: one year or two years Acorn shape: oblong elongated round tip: pointed or rounded Acorn size: length: ___________ width: ___________ Acorn cup: deep or shallow % of mature acorn covered by cup: Acorn cup shape: cap saucer bowl cup Acorn cup scales: thin, papery, leafike or thick, knobby, warty Scale tips: loose or pressed tightly to each other Acorn inner surface: densely fuzzy or hairless Based on the features above, is this a: Red/Black Oak White Oak Intermediate Oak Other Notable Features: Characteristics and Taxonomy of Quercus in California Genus Quercus = ~400-600 species Original publication: Linnaeus, Species Plantarum 2: 994. 1753 Sections in the subgenus Quercus: Red Oaks or Black Oaks 1. Foliage evergreen or deciduous (Quercus section Lobatae syn. 2. Mature bark gray to dark brown or black, smooth or Erythrobalanus) deeply furrowed, not scaly or papery ~195 species 3. Leaf blade lobes with bristles 4. Acorn requiring 2 seasons to mature (except Q. Example native species: agrifolia) kelloggii, agrifolia, wislizeni, parvula 5. Cup scales fattened, never knobby or warty, never var. -

The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition Supplement II December 2014

The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition Supplement II December 2014 In the pages that follow are treatments that have been revised since the publication of the Jepson eFlora, Revision 1 (July 2013). The information in these revisions is intended to supersede that in the second edition of The Jepson Manual (2012). The revised treatments, as well as errata and other small changes not noted here, are included in the Jepson eFlora (http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/IJM.html). For a list of errata and small changes in treatments that are not included here, please see: http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/JM12_errata.html Citation for the entire Jepson eFlora: Jepson Flora Project (eds.) [year] Jepson eFlora, http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/IJM.html [accessed on month, day, year] Citation for an individual treatment in this supplement: [Author of taxon treatment] 2014. [Taxon name], Revision 2, in Jepson Flora Project (eds.) Jepson eFlora, [URL for treatment]. Accessed on [month, day, year]. Copyright © 2014 Regents of the University of California Supplement II, Page 1 Summary of changes made in Revision 2 of the Jepson eFlora, December 2014 PTERIDACEAE *Pteridaceae key to genera: All of the CA members of Cheilanthes transferred to Myriopteris *Cheilanthes: Cheilanthes clevelandii D. C. Eaton changed to Myriopteris clevelandii (D. C. Eaton) Grusz & Windham, as native Cheilanthes cooperae D. C. Eaton changed to Myriopteris cooperae (D. C. Eaton) Grusz & Windham, as native Cheilanthes covillei Maxon changed to Myriopteris covillei (Maxon) Á. Löve & D. Löve, as native Cheilanthes feei T. Moore changed to Myriopteris gracilis Fée, as native Cheilanthes gracillima D. -

Plant-Wonders.Pdf

Assistant Professor, Dept. of Plant Biology & Plant Biotechnology, Guru Nanak College, Velachery, Chennai – 600 042. Seven Wonders of the World - Hanging Garden of Babylon The Garden of Babylon was built in about 600 BC. The Garden of Babylon was on the east bank of Euphrates River, about 50 kms south of Baghdad, Iraq. Ancient stories say King Nebuchadnezzar built the garden for his homesick wife. Unbelievable but real!! Coconut tree of Kerala, India.. Of the many wonders of plants, perhaps the most wonderful is not only that they are so varied and beautiful, but that they are also so clever at feeding themselves. Plants are autotrophs — "self nourishers." Using only energy from the sun, they can take up all the nourishment they need — water, minerals, carbon dioxide — directly from the world around them to manufacture their own roots and stems, leaves and flowers, fruits and seeds. If something is missing from that simple mix — if they don't get enough water, for example, or if the soil is lacking some of the minerals they need — they grow poorly or die. But their diet is limited, a few minerals, some H2O, some CO2, and energy from the sun. Makahiya or Sensitive Plant (Mimosa Pudica) Mimosa pudica or makahiya’s leaflets respond almost instantly to touch heat or wind by folding up and at the same time the petiole droop. The leaves recover after about 15 minutes. The Sensitive Plant is native to Central and South America, and gets it name because its leaflets fold in and droop when they are touched. -

Ecological Summary Report

Ecological Summary Report 56.8-acre Ameratrail Property Section 14, Township 26 South, Range 31 East Osceola County, Florida Prepared for: Snow Construction, Inc. 1136 New York Avenue St Cloud, FL 34769 October 2018 Table of Contents 1.0 Property Location 1 2.0 Survey Methodology 1 3.0 Soils 1 4.0 Vegetative Communities 2 5.0 Listed Wildlife Species 3 5.1 Bald Eagle 3 5.2 Gopher Tortoise 3 5.3 Red Cockaded Woodpecker 3 5.4 Florida Scrub-Jay 3 5.5 Eastern Indigo Snake 3 6.0 Ecological Impact Analysis 4 7.0 Conclusion 4 List of Figures: Figure 1 – Location Map Figure 2 – Aerial Photograph Figure 3 – USDA Soils Map Figure 4 – FLUCFCS Map This report presents the results of an ecological impact analysis for the Ameratrail project. The purpose of this analysis is to document existing site conditions, and the extent of impacts to jurisdictional wetlands and surface waters, as well as state and federally-listed species and their habitats. This information is intended to support Environmental Resource Permitting through the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD). 1.0 PROPERTY LOCATION The property consists of approximately 56.8 acres and is located southeast of the intersection of Old Melbourne Highway and US Highway 192 within Section 14, Township 26 South, Range 31 East, in Osceola County. The property consists of Osceola County tax parcel 14-26-31-0000-0010-0000. A location map and an aerial photograph have been provided as Figures 1 and 2, respectively. 2.0 SURVEY METHODOLOGY Prior to visiting the site, Austin Environmental Consultants, Inc. -

Species Profile: Quercus Oglethorpensis

Conservation Gap Analysis of Native U.S. Oaks Species profile: Quercus oglethorpensis Emily Beckman, Matt Lobdell, Abby Meyer, Murphy Westwood SPECIES OF CONSERVATION CONCERN CALIFORNIA SOUTHWESTERN U.S. SOUTHEASTERN U.S. Channel Island endemics: Texas limited-range endemics State endemics: Quercus pacifica, Quercus tomentella Quercus carmenensis, Quercus acerifolia, Quercus boyntonii Quercus graciliformis, Quercus hinckleyi, Southern region: Quercus robusta, Quercus tardifolia Concentrated in Florida: Quercus cedrosensis, Quercus dumosa, Quercus chapmanii, Quercus inopina, Quercus engelmannii Concentrated in Arizona: Quercus pumila Quercus ajoensis, Quercus palmeri, Northern region and / Quercus toumeyi Broad distribution: or broad distribution: Quercus arkansana, Quercus austrina, Quercus lobata, Quercus parvula, Broad distribution: Quercus georgiana, Quercus sadleriana Quercus havardii, Quercus laceyi Quercus oglethorpensis, Quercus similis Quercus oglethorpensis W.H.Duncan Synonyms: N/A Common Names: Oglethorpe oak Species profile co-author: Matt Lobdell, The Morton Arboretum Suggested citation: Beckman, E., Lobdell, M., Meyer, A., & Westwood, M. (2019). Quercus oglethorpensis W.H.Duncan. In Beckman, E., Meyer, A., Man, G., Pivorunas, D., Denvir, A., Gill, D., Shaw, K., & Westwood, M. Conservation Gap Analysis of Native U.S. Oaks (pp. 152-157). Lisle, IL: The Morton Arboretum. Retrieved from https://www.mortonarb.org/files/species-profile-quercus-oglethorpensis.pdf Figure 1. County-level distribution map for Quercus oglethorpensis. Source: Biota of North America Program (BONAP).4 Matt Lobdell DISTRIBUTION AND ECOLOGY Quercus oglethorpensis, or Oglethorpe oak, has a disjointed distribution across the southern U.S. Smaller clusters of localities exist in northeastern Louisiana, southeastern Mississippi, and southwestern Alabama, and a more extensive and well-known distribution extends from northeastern Georgia across the border into South Carolina. -

Key to Leaves of Eastern Native Oaks

FHTET-2003-01 January 2003 Front Cover: Clockwise from top left: white oak (Q. alba) acorns; willow oak (Q. phellos) leaves and acorns; Georgia oak (Q. georgiana) leaf; chinkapin oak (Q. muehlenbergii) acorns; scarlet oak (Q. coccinea) leaf; Texas live oak (Q. fusiformis) acorns; runner oak (Q. pumila) leaves and acorns; background bur oak (Q. macrocarpa) bark. (Design, D. Binion) Back Cover: Swamp chestnut oak (Q. michauxii) leaves and acorns. (Design, D. Binion) FOREST HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ENTERPRISE TEAM TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER Oak Identification Field Guide to Native Oak Species of Eastern North America John Stein and Denise Binion Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team USDA Forest Service 180 Canfield St., Morgantown, WV 26505 Robert Acciavatti Forest Health Protection Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry USDA Forest Service 180 Canfield St., Morgantown, WV 26505 United States Forest FHTET-2003-01 Department of Service January 2003 Agriculture NORTH AMERICA 100th Meridian ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to thank all those who helped with this publication. We are grateful for permission to use the drawings illustrated by John K. Myers, Flagstaff, AZ, published in the Flora of North America, North of Mexico, vol. 3 (Jensen 1997). We thank Drs. Cynthia Huebner and Jim Colbert, U.S. Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station, Disturbance Ecology and Management of Oak-Dominated Forests, Morgantown, WV; Dr. Martin MacKenzie, U.S. Forest Service, Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry, Forest Health Protection, Morgantown, WV; Dr. Steven L. Stephenson, Department of Biology, Fairmont State College, Fairmont, WV; Dr. Donna Ford-Werntz, Eberly College of Arts and Sciences, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV; Dr. -

95 Oak Ecosystem Restoration on Santa Catalina Island, California

95 QUANTIFICATION OF FOG INPUT AND USE BY QUERCUS PACIFICA ON SANTA CATALINA ISLAND Shaun Evola and Darren R. Sandquist Department of Biological Science, California State University, Fullerton 800 N. State College Blvd., Fullerton, CA 92834 USA Email address for corresponding author (D. R. Sandquist): [email protected] ABSTRACT: The proportion of water input resulting from fog, and the impact of canopy dieback on fog-water input, was measured throughout 2005 in a Quercus pacifica-dominated woodland of Santa Catalina Island. Stable isotopes of oxygen were measured in water samples from fog, rain and soils and compared to those found in stem-water from trees in order to identify the extent to which oak trees use different water sources, including fog drip, in their transpirational stream. In summer 2005, fog drip contributed up to 29 % of water found in the upper soil layers of the oak woodland but oxygen isotope ratios in stem water suggest that oak trees are using little if any of this water, instead depending primarily on water from a deeper source. Fog drip measurements indicate that the oak canopy in this system actually inhibits fog from reaching soil underneath the trees; however, fog may contribute additional water in areas with no canopy. Recent observations on Santa Catalina show a significant decline in oak woodlands, with replacement by non-native grasslands. The results of this study indicate that as canopy dieback and oak mortality continue additional water may become available for these invasive grasses. KEYWORDS: Fog drip, oak woodland, Quercus pacifica, Santa Catalina Island, stable isotopes, water use.