Activism After Seattle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACRL News Issue (B) of College & Research Libraries

winner receives $150, a certificate, a one-year sub cluding tax and land records, population and elec scription to the museum’s publication, The Old tion statistics, and period diaries to shape a social Sturbridge Visitor, and a five-year membership to portrait of not one community, but of an entire ge the Old Sturbridge Village Research Library Soci ographic region. ety. Roth’s book uses a great variety of sources in PEOPLE People in the news Committee of NAAL which developed the proce dure for the NAAL reimbursement program that Francesca Allegri, formerly head of Informa has been successful in promoting the use of library tion Management Education Services at the Uni resources throughout the state. Her committee also versity of North Carolina Health Sciences Library, developed the charge to seek funding to improve Chapel Hill, relocated to Champaign, Illinois, in the document delivery network. As a result, NAAL March. She will be teaching, consulting and writ will be funded in 1989 to install telefacsimile ing in the areas of user education and information equipment in all general and cooperative libraries. management. She continues as editor of the column, “Information Management Education,” Profiles in Medical Reference Services Quarterly. Annie G. King, library director at Tuskegee In Judith Adams, head of the Humanities Depart stitute, Alabama, has been awarded the Distin ment at the Auburn University Libraries, has been guished Service Award presented by the Alabama appointed director of the Lockwood Library at the Library Association to an individual who has made State University of New a significant contribution toward the development York at Buffalo. -

Commencement 1961-1970

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY BALTIMORE, MARYLAND Conferring of Degrees at the close of the eighty-sixth academic year JUNE 12, 1962 Keyser Quadrangle Homewood ORDER OF PROCESSION The Graduates Marshals Carpenter Edgar A. | whs H. J. Johnson Alphonse Chapanis Richard J. Kok.es Carl F. Christ James L. Kuethe Stanley Corrsin Alvin Nason Palmer Futcher Peter E. Wagner John W. Gryder Charles M. Wylie * The Faculties Marshals James W. Poultney and John Walton * The Deans, The Trustees and Honored Guests Marshals Nathan Edelman and M. Gordon Wolman * The Chaplain The Presentors of the Honorary Degree Candidate The Candidates The Commencement Speaker The Chairman of the Board of Trustees The President of the University Chief Marshal Donald H. Andrews Assistant Marshal Francis H. Clauser * For the Presentation of Diplomas Marshals Maurice J. Bessman Stewart H. Hulse, Jr. William H. Huggins W. Kelso Morrill The ushers are undergraduate students of The Johns Hopkins University ORDER OF EVENTS Milton Stover Eisenhower, President of the University, presiding PROCESSIONAL MARCHE SOLENNELLE — FELIX BOROWSKI John H. Elterman, Organist The audience is requested to stand as the Academic Procession moves into the area and to remain standing until after the Invocation and the singing of the National Anthem. INVOCATION The Right Reverend Noble C. Powell * THE STAR SPANGLED BANNER THE UNIVERSITY ODE * GREETINGS TO PARENTS CHARLES S. GARLAND Chairman of the Board of Trustees * CONFERRING OF HONORARY DEGREES WILLIAM BENNETT KOUWENHOVEN Presented by Ferdinand Hamburger, Jr. JULIUS ADAMS STRATTON Presented by Francis H. Clauser * ADDRESS JULIUS ADAMS STRATTON President, Massachusetts Institute of Technology ORDER OF EVENTS Continued CONFERRING OF DEGREES ON CANDIDATES Presented by Dean G. -

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Bulletin

PRES IDENT'S REPO RT ISSUE Volume ninety, Number two a November, 1954 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY BULLETIN _ _I ___ I __ ~~~ Entered July 3, 1933, at the Post Ofice, Boston, Massachusetts, as second-class matter, under Act of Congress of August 24, 1912 Published by the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, Cambridge Station, Boston, Massachusetts, in March, June, July, October and November. Issucs of the Bulletin include the REPORTS OF THE PRESIDENT and OF THE TREASURER, the SUMMER SESSION CATALOGUE, the GENERAL CATALOGUE, and THIS IS M. I. T. Published under the auspices of the M. I. T. Ofice of Publications __ Massachusetts Institute of Technology Bulletin PRESIDENT'S REPORT ISSUE Volume 90, Number 2 . November, 1954 _~1·_1__1_·_1 1--~111.1~^~-·~-····IIY·i The Corporation, 1954-1955 President: JAMES R. KILLIAN, JR. Vice-President and Provost: JULIUS A. STRATTON Vice-President and Treasurer:JosEPH J. SNYDER Vice-President for Industrial and Government Relations: EDWARD L. COCHRANE Secretary: WALTER HUMPHREYS LIFE MEMBERS WALTER HUMPHREYS RALPH E. FLANDERS DUNCAN R. LINSLEY JOHN R. MACOMBER JAMES M. BARKER THOMAS D. CABOT ALFRED L. LooMIS THOMAS C. DESMOND CRAWFORD H. GREENEWAL r HARLOW SHAPLEY J. WILLARD HAYDEN JAMES McGowAN, JR. ALFRED P. SLOAN, JR. MARSHALL B. DALTON HAROLD B. RICHMOND REDFIELD PROCTOR ROBERT E. WILSON LLOYD D. BRACE GODPREY L. CABOT DONALD F. CARPENTER THOMAS D'A. BROPHY BRADLEY DEWEY HORACE S. FORD WILLIAM A. COOLIDGE FRANCIS J. CHESTERMAN GEORGE A. SLOAN MERVIN J. KELLY VANNEVAR BUSH WALTER J. BEADLE ROBERT T. HASLAM WILLIAM EMERSON B. EDWIN HUTCHINSON RALPH LOWELL IRVING W. -

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Time-Line 1846: William Barton Rogers, Founder of MIT

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Time-Line 1846: William Barton Rogers, founder of MIT https://libraries.mit.edu/mithistory/mit-facts/ The idea for MIT originated with William Barton Rogers who is classed as its founder and was MIT’s first president. Rogers was a professor of natural philosophy at the College of William and Mary when he described his vision for a “new polytechnic institute” in a letter to his brother Henry in 1846. 1861: MIT granted its official charter: ‘a society of arts, a museum of arts, and a school of industrial science’ https://libraries.mit.edu/mithistory/mit-facts/ MIT was founded on April 10, 1861, the date it was granted its official charter by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. This was two days before the start of the American Civil War. Over the next several years plans were made and funds raised, with the first classes beginning in 1865. From the Acts of 1861, Section 1: https://corporation.mit.edu/sites/default/files/images/charter.pdf “….Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for the purpose of instituting and maintaining a society of arts, a museum of arts, and a school of industrial science, and aiding generally, by suitable means, the advancement, development and practical application of science in connection with arts, agriculture, manufacture and commerce…” 1862: MIT’s first meeting https://www.scribd.com/document/488808257/669-Massachusetts-Institute-of-Technology-Society-of- Arts-Records William Barton Rogers issued a notice for the first meeting of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Seventeen persons responded to the notice and the meeting was convened on April 8 at the rooms of the Boston Board of Trade. -

Hollow Cathode Plasma Penetration Study

. ,: I I ’ NASA CONTRACTOR ;NASA CR-660 REPORT 0 *o *o I PL U 4 GPO PRICE $ v) ,-’ 4 CFST! PRICE(S) $ c/ z Hrrrd copy (HC) Microfiche (MF) .& !! If63 Je!y 65 I’ I HOLLOW CATHODE PLASMA PENETRATION STUDY by Grubum Rzcssell, Jumes Litton, und Po B. Myers Prepared by BUNKER-RAM0 CORPORATION Canoga Park, Calif. for Electronics Research Center NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, D. C. DECEMBER 1966 . / NASA CR-660 c HOLLOW CATHODE PLASMA PENETRATION STUDY By Graham Russell, James Litton, and P. B. Myers Distribution of this report is provided in the interest of information exchange. Responsibility €or the contents resides in the author or organization that prepared it. Prepared under Contract No. NAS 12-9 by BUNKER-RAM0 CORPORATION Canoga Park, Calif. for Electronics Research Center NATIONAL AERONAUT ICs AND SPACE ADMlN ISTRATION For sale by the Clearinghouse for Federal Scientific and Technical Information Springfield, Virginia 22151 - Price $2.00 t I' I FOREWORD This final report documents and summarizes the study on hollow cathode plasma penetration conducted by The Bunker -Ram0 Corporation for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Electronics Research Center. The report is submitted in compliance with the re- quirements of Contract NAS 12-9. iii I i i t’ CONTENTS Foreword ............................... iii I. Introduction ............................. I- 1 11. Summary of Study Effort, by Statement of Work Items .................................. 11- 1 111. Discussion of Technical Effort ................. LII-1 A. Effort of First.Three Quarters .............. 111-1 B. Summary of the First Three Quarters’ Results , . LII-5 C. Final Quarter’s Effort and Results ........... -

Faculty News Letter, 1963-1966

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/facultynewslett196366coll - The Gollege of "William & <JXCary in Virginia News Bureau CA 9-3000, Ext. 226 Williamsburg FACULTY NEWSLETTER Friday, September 27, 1963 EARL GREGG SWEM LIBRARY - PROGRESS REPORT October 11— the Friday of Homecorrdng Weekend— has been set as the date for ceremonies attendant upon groundbreaking for the new general library. Whether groundbreaking will literally occur at that time now depends upon the speed with which construction contracts can be 3etj but the ceremonies will be held at Phi Beta Kappa Memorial Hall at k p.m. on October 11 in recognition of the significance of the building itself, so long needed by the faculty and student community. Working drawings for the new library were revised early in the summer in accordance with requests from the Board of Visitors. Final drawings then had to be approved by the Beard, the State Art Commission and various state officers in Richmond. The completion of detailed specifications for the building occupied the rest of the summer months. The final draft of the plans and specifications was submitted to the Governor's office on September 20. Named for Earl Gregg Swem, librarian emeritus and a beloved William and Mary figure- the new library will take about two years to complete. It will be the third unit in a new campus area now consisting of Phi Beta Kappa Memorial Hall and the William Small Physical Laboratory which is scheduled for completion early in l°61j. -

Julius Adams Stratton 1901—1994

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES JULIUS ADAMS STRATTON 1 9 0 1 — 1 9 9 4 A Biographical Memoir by PAUL E. GRAY Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 2007 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON, D.C. MIT Museum JULIUS ADAMS STRATTON May 18, 1901–June 22, 1994 BY PAUL E . GRAY AY, AS HE WAS KNOWN by nearly all who worked with him, Jserved the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the Radia- tion Laboratory at MIT, the federal government, the National Academies, and the Ford Foundation during his long and productive life. His work at MIT, as a member of the faculty and subsequently as provost, chancellor, and president, was vital to the development of both research and education during periods of rapid growth and change at MIT. EARLY YEARS Stratton was born on May 18, 1901, in Seattle, Wash- ington. His father, Julius A. Stratton, was an attorney who founded a law firm well known and respected throughout the northwest; later he became a judge. His mother, Laura Adams Stratton, was an accomplished pianist. Following his father’s retirement in 1906, the family moved to Germany, where young Julius attended school through age nine and became fluent in German. In 1910 the family returned to Seattle, where he completed his public school education. Stratton came to MIT, with which he was associated for 74 years, as the result of an accident at sea and on the advice of a fellow student. -

MIT Facts2018-Final.Indd

MIT Facts 2018 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Ave, Cambridge, MA 02139-4307 617.253.1000 | web.mit.edu MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. MIT welcomes the world’s best talent. -

Memorial Tributes: Volume 3

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/1384 SHARE Memorial Tributes: Volume 3 DETAILS 381 pages | 6 x 9 | HARDBACK ISBN 978-0-309-03939-0 | DOI 10.17226/1384 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK National Academy of Engineering FIND RELATED TITLES Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 3 i Memorial Tributes National Academy of Engineering Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 3 ii Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 3 iii Memorial Tributes Volume 3 National Academy of Engineering of the United States of America NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS Washington, D.C. 1989 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 3 iv National Academy Press 2101 Constitution Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20418 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data (Revised for vol. 3) National Academy of Engineering. Memorial tributes. Vol. 3– imprint: Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. 1. Engineers—United States—Biography. I. Title. TA139.N34 1979 620'.0092`2 79-21053 ISBN 0-309-03482-5 (v. -

Recountings Tells of the Influential US Mathematics Department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Through Interviews with a Dozen Faculty Members

“Recountings tells of the influential US mathematics department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) through interviews with a dozen faculty members . The interest in teaching among these senior faculty members is broad and deep. The professors share their strategies for achieving research success, from working on prize problems to developing an intuitive feel for proofs. They explain how new research directions have come from interactions with students and colleagues or from writing a review article. The insights in [this book] will inspire mathematicians and scientists to come.” —Eric Altschuler, NATURE “Students currently contemplating or pursuing a mathematics-related career should find MIT’s oral history illuminating and thought provoking. It is a remarkable institutional story, recalled and superbly narrated by those much concerned.” —Mathematics Teacher “Recountings provides a history of the MIT Mathematics Department, as told through interviews conducted with 12 of its current and former faculty members, plus Zipporah (Fagi) Levinson, widow of Norman Levinson (and one-time ‘den mother’ of the department). What emerges is a piecemeal yet compelling portrait of the department’s rapid post-WW II transformation from a program largely focused on offering mathematical instruction to engineering students, to a world-class research enterprise. Highly recommended.” —CHOICE “Though never in the eye of popular culture, these men kept society advancing with their minds. Recountings is a collection of interviews and anecdotes from the geniuses of MIT who have pursued mathematics as their life’s careers and obsessions. These men have been responsible for major scientific advances throughout history . Recountings is an intriguing look at mathematics and the men behind it.” —Library Bookwatch “It’s full of really good stuff. -

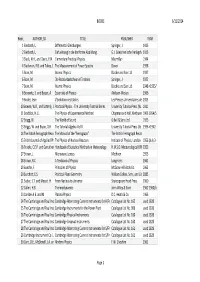

Call Number Author Title Date AG5 .B64 2006 New Book of Knowledge

call number author Title date AG5 .B64 2006 New book of knowledge. 2006 John Simon Guggenheim memorial foundation. Reports of the secretary & of the AS911.J6 treasurer. Snow, C. P. (Charles Percy), AZ361 .S56 1905-1980 Two cultures and the scientific revolution, the two cultures and a second look 1963 BD632 .F67 Formánek, Miloslav. Časoprostor v politice : některé problémy fyzikalismu / Miloslav Formánek. Reichenbach, Hans, 1891- Philosophy of space & time. Translated by Maria Reichenbach and John Freund. BD632 .R413 1953. With introductory remarks by Rudolf Carnap. BD632.G92 Gurnbaum, Adolf Philosophical Problems of Space of Time BD638 .P73 1996 Price, Huw, 1953- Price. 1996 BH301.N3 H55 1985 Hildebrandt, Stefan. Mathematics and optimal form / Stefan Hildebrandt, Anthony Tromba. BT130 .B69 1983 Brams, Steven J. omniscience, omnipotence, immortality, and incomprehensibility / Steven J. Brams. Berry, Adrian, 1937- 1996 CB161 .B459 1996 Next 500 years : life in the coming millennium / Adrian Berry. 1982 E158 .A48 1982 America from the road / Reader's digest. Forbes, Steve, 1947- 1999 E885 .F67 1999 New birth of freedom : vision for America / Steve Forbes. G1019 .R47 1955 Rand McNally and Company. Standard world atlas. G70.4 .S77 1992 oversized Strain, Priscilla. Looking at earth / Priscilla Strain & Frederick Engle. 1992 GB55 .G313 Gaddum, Leonard William, Harold L. Knowles. 1953 Fairbridge, Rhodes W. GC9 .F3 (Rhodes Whitmore), 1914- 2006. Encyclopedia of oceanography, edited by Rhodes W. Fairbridge. Challenge of man's future; an inquiry concerning the condition of man during the GF31 .B68 Brown, Harrison, 1917-1986. years that lie ahead. GF47 .M63 Moran, Joseph M. [and] James H. Wiersma. 1973 Anderson, Walt, 1933- 1996 GN281.4 .A53 1996 Evolution isn't what it used to be : the augmented animal and the whole wired world / Walter Truett Anderson. -

List of Books at 23 Oct 2014

BOOKS 6/11/2014 Book_ AUTHOR_SX TITLE PUBLISHER YEAR 1Bierbach, L. Differential Gleichungen. Springer, J. 1923 2Bierbach, L. Einfuehrung in die konforme Abbildung. G.J. Goeschen'sche Verlagsh 1915 3Black, N.H., and Davis, H.N. Elementary Practical Physics Macmillan 1944 4Blackman, R.B. and Tukey, J. The Measurement of Power Spectra Dover 1958 5Born, M. Atomic Physics Blackie and Son Ltd. 1937 6Born, M. Die Relativitaetstheorie Einsteins. Springer, J. 1922 7Born, M. Atomic Physics Blackie and Son Ltd. 1948 <1935/ 8Borowitz, S. and Beiser, A. Essentials of Physics Addison‐Wesley 1966 9Bosler, Jean. L'Evolution des Etoiles Les Presses Universitaires de 1923 10 Bowen, W.R., and Satterly, J. Practical Physics ‐ The University Tutorial Series University Tutorial Press (W. 1911 11 Braddick, H.J.J. The Physics of Experimental Method Chapman and Hall, Methuen 1966 1954/5 12 Bragg, W. The World of Sound G Bell & Sons Ltd 1923 13 Briggs, W. and Bryan, G.H. The Tutorial Algebra Vol II University Tutorial Press Ltd. 1956 <1942‐ 14 The British Ferrograph Reco The Manual of the "Ferrograph" The British Ferrograph Recor 15 British Journal of Applied Ph The Physics of Nuclear Reactors Institute of Physics, London 1956 (July 3‐ 16 Brooks, C.E.P. and Carruther Handbook of Statistical Methods in Meteorology H.M.S.O. Meteorological Offi 1953 17 Brown, J. Microwave Lenses Methuen 1953 18 Brown, R.C. A Textbook of Physics Longmans 1961 19 Bueche, F. Principles of Physics McGraw‐Hill Book Co. 1965 20 Burchett, E.S. Practical Plane Geometry William Collins, Sons, and Co 1885 21 Butler, S.T.