Recountings Tells of the Influential US Mathematics Department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Through Interviews with a Dozen Faculty Members

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2006 Annual Report

Contents Clay Mathematics Institute 2006 James A. Carlson Letter from the President 2 Recognizing Achievement Fields Medal Winner Terence Tao 3 Persi Diaconis Mathematics & Magic Tricks 4 Annual Meeting Clay Lectures at Cambridge University 6 Researchers, Workshops & Conferences Summary of 2006 Research Activities 8 Profile Interview with Research Fellow Ben Green 10 Davar Khoshnevisan Normal Numbers are Normal 15 Feature Article CMI—Göttingen Library Project: 16 Eugene Chislenko The Felix Klein Protocols Digitized The Klein Protokolle 18 Summer School Arithmetic Geometry at the Mathematisches Institut, Göttingen, Germany 22 Program Overview The Ross Program at Ohio State University 24 PROMYS at Boston University Institute News Awards & Honors 26 Deadlines Nominations, Proposals and Applications 32 Publications Selected Articles by Research Fellows 33 Books & Videos Activities 2007 Institute Calendar 36 2006 Another major change this year concerns the editorial board for the Clay Mathematics Institute Monograph Series, published jointly with the American Mathematical Society. Simon Donaldson and Andrew Wiles will serve as editors-in-chief, while I will serve as managing editor. Associate editors are Brian Conrad, Ingrid Daubechies, Charles Fefferman, János Kollár, Andrei Okounkov, David Morrison, Cliff Taubes, Peter Ozsváth, and Karen Smith. The Monograph Series publishes Letter from the president selected expositions of recent developments, both in emerging areas and in older subjects transformed by new insights or unifying ideas. The next volume in the series will be Ricci Flow and the Poincaré Conjecture, by John Morgan and Gang Tian. Their book will appear in the summer of 2007. In related publishing news, the Institute has had the complete record of the Göttingen seminars of Felix Klein, 1872–1912, digitized and made available on James Carlson. -

A Historical Perspective of Spectrum Estimation

PROCEEDINGSIEEE, OF THE VOL. 70, NO. 9, SEPTEMBER885 1982 A Historical Perspective of Spectrum Estimation ENDERS A. ROBINSON Invited Paper Alwhrct-The prehistory of spectral estimation has its mots in an- times, credit for the empirical discovery of spectra goes to the cient times with the development of the calendar and the clock The diversified genius of Sir Isaac Newton [ 11. But the great in- work of F’ythagom in 600 B.C. on the laws of musical harmony found mathematical expression in the eighteenthcentury in terms of the wave terest in spectral analysis made its appearanceonly a little equation. The strueto understand the solution of the wave equation more than a century ago. The prominent German chemist was fhlly resolved by Jean Baptiste Joseph de Fourier in 1807 with Robert Wilhelm Bunsen (18 1 1-1899) repeated Newton’s his introduction of the Fourier series TheFourier theory was ex- experiment of the glass prism. Only Bunsen did not use the tended to the case of arbitrary orthogollpl functions by Stmn and sun’s rays Newton did. Newtonhad found that aray of Liowillein 1836. The Stum+Liouville theory led to the greatest as empirical sum of spectral analysis yet obbhed, namely the formulo sunlight is expanded into a band of many colors, the spectrum tion of quantum mechnnics as given by Heisenberg and SchrMngm in of the rainbow. In Bunsen’s experiment, the role of pure sun- 1925 and 1926. In 1929 John von Neumann put the spectral theory of light was replaced by the burning of an old rag that had been the atom on a Turn mathematical foundation in his spectral represent, soaked in a salt solution (sodium chloride). -

Bfm:978-1-4612-2582-9/1.Pdf

Progress in Mathematics Volume 131 Series Editors Hyman Bass Joseph Oesterle Alan Weinstein Functional Analysis on the Eve of the 21st Century Volume I In Honor of the Eightieth Birthday of I. M. Gelfand Simon Gindikin James Lepowsky Robert L. Wilson Editors Birkhauser Boston • Basel • Berlin Simon Gindikin James Lepowsky Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics Rutgers University Rutgers University New Brunswick, NJ 08903 New Brunswick, NJ 08903 Robert L. Wilson Department of Mathematics Rutgers University New Brunswick, NJ 08903 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Functional analysis on the eve of the 21 st century in honor of the 80th birthday 0fI. M. Gelfand I [edited) by S. Gindikin, 1. Lepowsky, R. Wilson. p. cm. -- (Progress in mathematics ; vol. 131) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13:978-1-4612-7590-9 e-ISBN-13:978-1-4612-2582-9 DOl: 10.1007/978-1-4612-2582-9 1. Functional analysis. I. Gel'fand, I. M. (lzraU' Moiseevich) II. Gindikin, S. G. (Semen Grigor'evich) III. Lepowsky, J. (James) IV. Wilson, R. (Robert), 1946- . V. Series: Progress in mathematics (Boston, Mass.) ; vol. 131. QA321.F856 1995 95-20760 515'.7--dc20 CIP Printed on acid-free paper d»® Birkhiiuser ltGD © 1995 Birkhliuser Boston Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1995 Copyright is not claimed for works of u.s. Government employees. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright owner. -

Martin Gardner Receives JPBM Communications Award

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIAnON OF AMERICA Martin Gardner Receives JPBM voIome 14, Number 4 Communications Award Martin Gardner has been named the 1994 the United States Navy recipient of the Joint Policy Board for Math and served until the end ematics Communications Award. Author of of the Second World In this Issue numerous books and articles about mathemat War. He began his Sci ics' Gardner isbest known for thelong-running entific Americancolumn "Mathematical Games" column in Scientific in December 1956. 4 CD-ROM American. For nearly forty years, Gardner, The MAA is proud to count Gardneras one of its Textbooks and through his column and books, has exertedan authors. He has published four books with the enormous influence on mathematicians and Calculus Association, with three more in thepipeline. This students of mathematics. September, he begins "Gardner's Gatherings," 6 Open Secrets When asked about the appeal of mathemat a new column in Math Horizons. ics, Gardner said, "It's just the patterns, and Previous JPBM Communications Awards have their order-and their beauty: the way it all gone to James Gleick, author of Chaos; Hugh 8 Section Awards fits together so it all comes out right in the Whitemore for the play Breaking the Code; Ivars end." for Distinguished Peterson, author of several books and associate Teaching Gardner graduated Phi Beta Kappa in phi editor of Science News; and Joel Schneider, losophy from the University of Chicago in content director for the Children's Television 10 Personal Opinion 1936, and then pursued graduate work in the Workshop's Square One TV. -

Publications of Members, 1930-1954

THE INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY PUBLICATIONS OF MEMBERS 1930 • 1954 PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY . 1955 COPYRIGHT 1955, BY THE INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, PRINCETON, N.J. CONTENTS FOREWORD 3 BIBLIOGRAPHY 9 DIRECTORY OF INSTITUTE MEMBERS, 1930-1954 205 MEMBERS WITH APPOINTMENTS OF LONG TERM 265 TRUSTEES 269 buH FOREWORD FOREWORD Publication of this bibliography marks the 25th Anniversary of the foundation of the Institute for Advanced Study. The certificate of incorporation of the Institute was signed on the 20th day of May, 1930. The first academic appointments, naming Albert Einstein and Oswald Veblen as Professors at the Institute, were approved two and one- half years later, in initiation of academic work. The Institute for Advanced Study is devoted to the encouragement, support and patronage of learning—of science, in the old, broad, undifferentiated sense of the word. The Institute partakes of the character both of a university and of a research institute j but it also differs in significant ways from both. It is unlike a university, for instance, in its small size—its academic membership at any one time numbers only a little over a hundred. It is unlike a university in that it has no formal curriculum, no scheduled courses of instruction, no commitment that all branches of learning be rep- resented in its faculty and members. It is unlike a research institute in that its purposes are broader, that it supports many separate fields of study, that, with one exception, it maintains no laboratories; and above all in that it welcomes temporary members, whose intellectual development and growth are one of its principal purposes. -

Math Spans All Dimensions

March 2000 THE NEWSLETTER OF THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Math Spans All Dimensions April 2000 is Math Awareness Month Interactive version of the complete poster is available at: http://mam2000.mathforum.com/ FOCUS March 2000 FOCUS is published by the Mathematical Association of America in January. February. March. April. May/June. August/September. FOCUS October. November. and December. a Editor: Fernando Gouvea. Colby College; March 2000 [email protected] Managing Editor: Carol Baxter. MAA Volume 20. Number 3 [email protected] Senior Writer: Harry Waldman. MAA In This Issue [email protected] Please address advertising inquiries to: 3 "Math Spans All Dimensions" During April Math Awareness Carol Baxter. MAA; [email protected] Month President: Thomas Banchoff. Brown University 3 Felix Browder Named Recipient of National Medal of Science First Vice-President: Barbara Osofsky. By Don Albers Second Vice-President: Frank Morgan. Secretary: Martha Siegel. Treasurer: Gerald 4 Updating the NCTM Standards J. Porter By Kenneth A. Ross Executive Director: Tina Straley 5 A Different Pencil Associate Executive Director and Direc Moving Our Focus from Teachers to Students tor of Publications and Electronic Services: Donald J. Albers By Ed Dubinsky FOCUS Editorial Board: Gerald 6 Mathematics Across the Curriculum at Dartmouth Alexanderson; Donna Beers; J. Kevin By Dorothy I. Wallace Colligan; Ed Dubinsky; Bill Hawkins; Dan Kalman; Maeve McCarthy; Peter Renz; Annie 7 ARUME is the First SIGMAA Selden; Jon Scott; Ravi Vakil. Letters to the editor should be addressed to 8 Read This! Fernando Gouvea. Colby College. Dept. of Mathematics. Waterville. ME 04901. 8 Raoul Bott and Jean-Pierre Serre Share the Wolf Prize Subscription and membership questions 10 Call For Papers should be directed to the MAA Customer Thirteenth Annual MAA Undergraduate Student Paper Sessions Service Center. -

ACRL News Issue (B) of College & Research Libraries

winner receives $150, a certificate, a one-year sub cluding tax and land records, population and elec scription to the museum’s publication, The Old tion statistics, and period diaries to shape a social Sturbridge Visitor, and a five-year membership to portrait of not one community, but of an entire ge the Old Sturbridge Village Research Library Soci ographic region. ety. Roth’s book uses a great variety of sources in PEOPLE People in the news Committee of NAAL which developed the proce dure for the NAAL reimbursement program that Francesca Allegri, formerly head of Informa has been successful in promoting the use of library tion Management Education Services at the Uni resources throughout the state. Her committee also versity of North Carolina Health Sciences Library, developed the charge to seek funding to improve Chapel Hill, relocated to Champaign, Illinois, in the document delivery network. As a result, NAAL March. She will be teaching, consulting and writ will be funded in 1989 to install telefacsimile ing in the areas of user education and information equipment in all general and cooperative libraries. management. She continues as editor of the column, “Information Management Education,” Profiles in Medical Reference Services Quarterly. Annie G. King, library director at Tuskegee In Judith Adams, head of the Humanities Depart stitute, Alabama, has been awarded the Distin ment at the Auburn University Libraries, has been guished Service Award presented by the Alabama appointed director of the Lockwood Library at the Library Association to an individual who has made State University of New a significant contribution toward the development York at Buffalo. -

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Reflection Positivity

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 55/2017 DOI: 10.4171/OWR/2017/55 Reflection Positivity Organised by Arthur Jaffe, Harvard Karl-Hermann Neeb, Erlangen Gestur Olafsson, Baton Rouge Benjamin Schlein, Z¨urich 26 November – 2 December 2017 Abstract. The main theme of the workshop was reflection positivity and its occurences in various areas of mathematics and physics, such as Representa- tion Theory, Quantum Field Theory, Noncommutative Geometry, Dynamical Systems, Analysis and Statistical Mechanics. Accordingly, the program was intrinsically interdisciplinary and included talks covering different aspects of reflection positivity. Mathematics Subject Classification (2010): 17B10, 22E65, 22E70, 81T08. Introduction by the Organisers The workshop on Reflection Positivity was organized by Arthur Jaffe (Cambridge, MA), Karl-Hermann Neeb (Erlangen), Gestur Olafsson´ (Baton Rouge) and Ben- jamin Schlein (Z¨urich) during the week November 27 to December 1, 2017. The meeting was attended by 53 participants from all over the world. It was organized around 24 lectures each of 50 minutes duration representing major recent advances or introducing to a specific aspect or application of reflection positivity. The meeting was exciting and highly successful. The quality of the lectures was outstanding. The exceptional atmosphere of the Oberwolfach Institute provided the optimal environment for bringing people from different areas together and to create an atmosphere of scientific interaction and cross-fertilization. In particular, people from different subcommunities exchanged ideas and this lead to new col- laborations that will probably stimulate progress in unexpected directions. 3264 Oberwolfach Report 55/2017 Reflection positivity (RP) emerged in the early 1970s in the work of Osterwalder and Schrader as one of their axioms for constructive quantum field theory ensuring the equivalence of their euclidean setup with Wightman fields. -

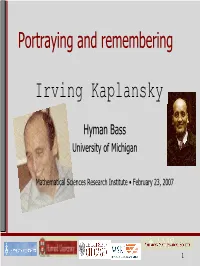

Irving Kaplansky

Portraying and remembering Irving Kaplansky Hyman Bass University of Michigan Mathematical Sciences Research Institute • February 23, 2007 1 Irving (“Kap”) Kaplansky “infinitely algebraic” “I liked the algebraic way of looking at things. I’m additionally fascinated when the algebraic method is applied to infinite objects.” 1917 - 2006 A Gallery of Portraits 2 Family portrait: Kap as son • Born 22 March, 1917 in Toronto, (youngest of 4 children) shortly after his parents emigrated to Canada from Poland. • Father Samuel: Studied to be a rabbi in Poland; worked as a tailor in Toronto. • Mother Anna: Little schooling, but enterprising: “Health Bread Bakeries” supported (& employed) the whole family 3 Kap’s father’s grandfather Kap’s father’s parents Kap (age 4) with family 4 Family Portrait: Kap as father • 1951: Married Chellie Brenner, a grad student at Harvard Warm hearted, ebullient, outwardly emotional (unlike Kap) • Three children: Steven, Alex, Lucy "He taught me and my brothers a lot, (including) what is really the most important lesson: to do the thing you love and not worry about making money." • Died 25 June, 2006, at Steven’s home in Sherman Oaks, CA Eight months before his death he was still doing mathematics. Steven asked, -“What are you working on, Dad?” -“It would take too long to explain.” 5 Kap & Chellie marry 1951 Family portrait, 1972 Alex Steven Lucy Kap Chellie 6 Kap – The perfect accompanist “At age 4, I was taken to a Yiddish musical, Die Goldene Kala. It was a revelation to me that there could be this kind of entertainment with music. -

Contemporary Mathematics 442

CONTEMPORARY MATHEMATICS 442 Lie Algebras, Vertex Operator Algebras and Their Applications International Conference in Honor of James Lepowsky and Robert Wilson on Their Sixtieth Birthdays May 17-21, 2005 North Carolina State University Raleigh, North Carolina Yi-Zhi Huang Kailash C. Misra Editors http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/conm/442 Lie Algebras, Vertex Operator Algebras and Their Applications In honor of James Lepowsky and Robert Wilson on their sixtieth birthdays CoNTEMPORARY MATHEMATICS 442 Lie Algebras, Vertex Operator Algebras and Their Applications International Conference in Honor of James Lepowsky and Robert Wilson on Their Sixtieth Birthdays May 17-21, 2005 North Carolina State University Raleigh, North Carolina Yi-Zhi Huang Kailash C. Misra Editors American Mathematical Society Providence, Rhode Island Editorial Board Dennis DeTurck, managing editor George Andrews Andreas Blass Abel Klein 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 17810, 17837, 17850, 17865, 17867, 17868, 17869, 81T40, 82823. Photograph of James Lepowsky and Robert Wilson is courtesy of Yi-Zhi Huang. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lie algebras, vertex operator algebras and their applications : an international conference in honor of James Lepowsky and Robert L. Wilson on their sixtieth birthdays, May 17-21, 2005, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina / Yi-Zhi Huang, Kailash Misra, editors. p. em. ~(Contemporary mathematics, ISSN 0271-4132: v. 442) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-0-8218-3986-7 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8218-3986-1 (alk. paper) 1. Lie algebras~Congresses. 2. Vertex operator algebras. 3. Representations of algebras~ Congresses. I. Leposwky, J. (James). II. Wilson, Robert L., 1946- III. Huang, Yi-Zhi, 1959- IV. -

About Lie-Rinehart Superalgebras Claude Roger

About Lie-Rinehart superalgebras Claude Roger To cite this version: Claude Roger. About Lie-Rinehart superalgebras. 2019. hal-02071706 HAL Id: hal-02071706 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02071706 Preprint submitted on 18 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. About Lie-Rinehart superalgebras Claude Rogera aInstitut Camille Jordan ,1 , Universit´ede Lyon, Universit´eLyon I, 43 boulevard du 11 novembre 1918, F-69622 Villeurbanne Cedex, France Keywords:Supermanifolds, Lie-Rinehart algebras, Fr¨olicher-Nijenhuis bracket, Nijenhuis-Richardson bracket, Schouten-Nijenhuis bracket. Mathematics Subject Classification (2010): .17B35, 17B66, 58A50 Abstract: We extend to the superalgebraic case the theory of Lie-Rinehart algebras and work out some examples concerning the most popular samples of supermanifolds. 1 Introduction The goal of this article is to discuss some properties of Lie-Rinehart structures in a superalgebraic context. Let's first sketch the classical case; a Lie-Rinehart algebra is a couple (A; L) where L is a Lie algebra on a base field k, A an associative and commutative k-algebra, with two operations 1. (A; L) ! L denoted by (a; X) ! aX, which induces a A-module structure on L, and 2. -

Fifth International Congress of Chinese Mathematicians Part 1

AMS/IP Studies in Advanced Mathematics S.-T. Yau, Series Editor Fifth International Congress of Chinese Mathematicians Part 1 Lizhen Ji Yat Sun Poon Lo Yang Shing-Tung Yau Editors American Mathematical Society • International Press Fifth International Congress of Chinese Mathematicians https://doi.org/10.1090/amsip/051.1 AMS/IP Studies in Advanced Mathematics Volume 51, Part 1 Fifth International Congress of Chinese Mathematicians Lizhen Ji Yat Sun Poon Lo Yang Shing-Tung Yau Editors American Mathematical Society • International Press Shing-Tung Yau, General Editor 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 05–XX, 08–XX, 11–XX, 14–XX, 22–XX, 35–XX, 37–XX, 53–XX, 58–XX, 62–XX, 65–XX, 20–XX, 30–XX, 80–XX, 83–XX, 90–XX. All photographs courtesy of International Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data International Congress of Chinese Mathematicians (5th : 2010 : Beijing, China) p. cm. (AMS/IP studies in advanced mathematics ; v. 51) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8218-7555-1 (set : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-8218-7586-5 (pt. 1 : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-8218-7587-2 (pt. 2 : alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—Congresses. I. Ji, Lizhen, 1964– II. Title. III. Title: 5th International Congress of Chinese Mathematicians. QA1.I746 2010 510—dc23 2011048032 Copying and reprinting. Material in this book may be reproduced by any means for edu- cational and scientific purposes without fee or permission with the exception of reproduction by services that collect fees for delivery of documents and provided that the customary acknowledg- ment of the source is given. This consent does not extend to other kinds of copying for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, or for resale.