Subjectivity in the Changing Landscape of Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

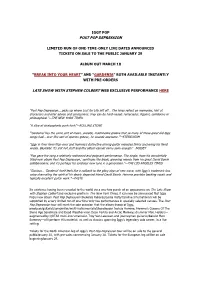

Post Pop Depression Late Show with Stephen Colbert

IGGY POP POST POP DEPRESSION LIMITED RUN OF ONE-TIME-ONLY LIVE DATES ANNOUNCED TICKETS ON SALE TO THE PUBLIC JANUARY 29 ALBUM OUT MARCH 18 “BREAK INTO YOUR HEART” AND “GARDENIA” BOTH AVAILABLE INSTANTLY WITH PRE-ORDERS LATE SHOW WITH STEPHEN COLBERT WEB EXCLUSIVE PERFORMANCE HERE “Post Pop Depression... picks up where Lust for Life left off… The lyrics reflect on memories, hint at characters and offer advice and confessions; they can be hard-nosed, remorseful, flippant, combative or philosophical.”—THE NEW YORK TIMES “A slice of stratospheric punk-funk”—ROLLING STONE “‘Gardenia’ has the same sort of mean, skeletal, machinelike groove that so many of those great old Iggy songs had… over this sort of spartan groove, he sounds awesome.”—STEREOGUM “Iggy in finer form than ever and Homme’s distinctive driving guitar melodies firmly anchoring his florid vocals. Basically: it’s shit hot stuff and this album cannot come soon enough”—NOISEY “Pop gave the song a relatively restrained and poignant performance. The single, from his wonderfully titled new album Post Pop Depression,’ continues the bleak, grooving moods from his great David Bowie collaborations, and it's perhaps his catchiest new tune in a generation.”—THE LOS ANGELES TIMES “Glorious… ’Gardenia’ itself feels like a callback to the glory days of new wave, with Iggy’s trademark low voice channeling the spirit of his dearly departed friend David Bowie. Homme provides backing vocals and typically excellent guitar work.”—PASTE Its existence having been revealed to the world via a one-two punch of an appearance on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert and exclusive profile in The New York Times, it can now be announced that Iggy Pop’s new album Post Pop Depression (Rekords Rekords/Loma Vista/Caroline International) will be supported by a very limited run of one-time-only live performances in specially selected venues. -

Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights Schedule 2

PHONOGRAPHIC PERFORMANCE COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED CONTROL OF MUSIC ON HOLD AND PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS SCHEDULE 2 001 (SoundExchange) (SME US Latin) Make Money Records (The 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 100% (BMG Rights Management (Australia) Orchard) 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) Music VIP Entertainment Inc. Pty Ltd) 10065544 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 441 (SoundExchange) 2. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) NRE Inc. (The Orchard) 100m Records (PPL) 777 (PPL) (SME US Latin) Ozner Entertainment Inc (The 100M Records (PPL) 786 (PPL) Orchard) 100mg Music (PPL) 1991 (Defensive Music Ltd) (SME US Latin) Regio Mex Music LLC (The 101 Production Music (101 Music Pty Ltd) 1991 (Lime Blue Music Limited) Orchard) 101 Records (PPL) !Handzup! Network (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) RVMK Records LLC (The Orchard) 104 Records (PPL) !K7 Records (!K7 Music GmbH) (SME US Latin) Up To Date Entertainment (The 10410Records (PPL) !K7 Records (PPL) Orchard) 106 Records (PPL) "12"" Monkeys" (Rights' Up SPRL) (SME US Latin) Vicktory Music Group (The 107 Records (PPL) $Profit Dolla$ Records,LLC. (PPL) Orchard) (SME US Latin) VP Records - New Masters 107 Records (SoundExchange) $treet Monopoly (SoundExchange) (The Orchard) 108 Pics llc. (SoundExchange) (Angel) 2 Publishing Company LCC (SME US Latin) VP Records Corp. (The 1080 Collective (1080 Collective) (SoundExchange) Orchard) (APC) (Apparel Music Classics) (PPL) (SZR) Music (The Orchard) 10am Records (PPL) (APD) (Apparel Music Digital) (PPL) (SZR) Music (PPL) 10Birds (SoundExchange) (APF) (Apparel Music Flash) (PPL) (The) Vinyl Stone (SoundExchange) 10E Records (PPL) (APL) (Apparel Music Ltd) (PPL) **** artistes (PPL) 10Man Productions (PPL) (ASCI) (SoundExchange) *Cutz (SoundExchange) 10T Records (SoundExchange) (Essential) Blay Vision (The Orchard) .DotBleep (SoundExchange) 10th Legion Records (The Orchard) (EV3) Evolution 3 Ent. -

Michael Shuman: “This Moment Has Been a Long Time Coming” | Nouse

Nouse Web Archives Michael Shuman: “This moment has been a long time coming” Page 1 of 6 News Comment MUSE. Politics Business Science Sport Roses Freshers Muse › Music › News Features Reviews Playlists Michael Shuman: “This moment has been a long time coming” Queens of the Stone Age bassist talks to Chris Owen about his acclaimed side project Mini Mansions with fellow band member Tyler Parkford Tuesday 29 September 2015 Image: Michelle Shiers, courtesy of pinpointmusic.com Michael Shuman, California rock star with all the trimmings and front man of Mini Mansions, is probably the only musician to have headlined Reading and Leeds and also played support slots for the likes of Royal Blood and Arctic Monkeys. It’s for the former that he, Tyler Parkford and Zach Dawes are preparing to take to the stage in the outer reaches of Yorkshire – Royal Blood chose to bring their 10 date UK tour to Bridlington of all places, and Mini Mansions have the task of warming up a rain-lashed, sold-out crowd at the iconic Spa. “This moment feels like it’s been a long time coming,” says Shuman, not on playing a support slot in Brid, but on finally giving the sidelined project the attention and lease of life it deserves. We’re backstage, and Mini Mansions’ dressing room is decorated with an untouched chiller full of Budweiser and a cluster of iMacs. The rock n’ roll life on the road is painted as the ultimate marriage of work and play, but the reality always seems to be a clear division between the two, particularly in the case of artists playing a high profile, sold out tour. -

Theaterstübchen in Kassel Auf

|Vorspiel|+ „Es ist ein Rausch, In Deutschland hat der „Verband deutscher Mutt er zu sein und eine Blumengeschäftsinhaber“ anno 1922/23 Plakate entworfen, auf denen der Schriftzug Würde, Vater zu sein“ „Ehret die Mutter“ prangerte. Der erste „rich- tige“ Muttertag wurde dann am 13. Mai 1923 Sully Prudhomme begangen, bevor ab 1926 die Förderung des Muttertages in die Hände der „Arbeitsgemein- schaft für Volksgesundung“ gegeben wurde. In Nazi-Deutschland wurde das Ganze natür- lich „politisch“ missbraucht: Es wurden beson- ders Mütter mit vielen Kindern gefeiert, weil ssieie ddenen „ar„arischenischen Nachwuchs“ der Erst Bier,ier, danndann „germanischen„germanischen Herrenrasse“ si- cherten. Da ddere zweite Sonntag iimm MMaiai 19491949 der 8. Mai, am Blumen 23. MaiMai 1949194 aber erst das m Mai ist es wiewiederi der sowesoweit:it: DieDie deutsdeutschec Grundgesetz Wer wagt, gewinnt! Eltern bekommenmmenm ihrenihren spezi-spezi- vverkündete wurde, Na, wen haben wir denn hier beim I ellen Platz imm Kalender.KKalender. CChristihristi bbeging die Bun- Wildwechseln erwischt? Himmelfahrt, ann deddemm derder VVatertag atertag desrepublik ih- >> Schreib uns eine Mail (Btr: wwvip) begangen wird,, fälfälltä lt aufauf dedenn 5. MaMaii, ren ersten Mut- an [email protected] mit der einen Donnerstag,taag,g, derddee MMuttertaguttertag tertag erst 1950. Lösung (z.B.: wwvip Heino)! ist drei Tage später,päteer, traditionell am BBis heute ist es so, Vielleicht gewinnt ihr was Schönes! zweiten Sonntagntagg im MaMaii. dassdas dem Muttertag, trotztrotz seines Status als Die meistenn vonv >> Richtig! nicnnicht-gesetzlicherht-ge Fei- In 04/16 hatten wir Kapelle uns sind mit dendeen ertag, hinsichtlich des Petra geblitzdingst. Abläufen vertraut:aut:t BluBlumenverkaufsme eine Muttern be-e- SonderstellungSono ders zukommt: kommt Blüm-- FloFloristenristent düdürfenr ihre Läden an chen, Pralinenn diesem TagTag geöffnetgeöffne lassen. -

()I Ncà H I -Di I= Tv Is Changing

#BXNCTCC SCH 3 -DIGIT 907 IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII I IIIIIII #BL2408043# APR06 A04 B0100 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 JUNE FOR MORE THAN 110 YEA 4 2005 NASHVILLE'S DUO I)l' I\ A IVI I C; HOT NEW TWOSOMES TAKE AIM AT COUNTRY SUCCESS >P.26 ()I NCà H I -DI_I= TV IS CHANGING... WILL LABELS BE READY FOR THE NEXT WINDFALL? >P.24 ' IVIAROON5: 'I'H 1= SOULFUL I3A N I) l'H Ar COULD A BILLBOARD STARS SPECIAL FEATURE >P.29 MI 3 $ 9US $8.99CAN 3> LESS IS MORE FOR `SATAN' >P.22 11 74470 02552 www.americanradiohistory.com Your potential. Our passion.'" p l aysf o rs u re Windows Media Choose your music. Choose your device. Know it's going to work. When your cevice and music service are compatible with each other, all you have to dc is choose the music that's compatible with you. Look for the PlaysForSure logo on a wide range of devices and music services. For a complete list go to playsforsure.com 2005 Microsoft Corp arion AU nghts reserved. Microsoft. MSII, MSN logo, the PtaysForaire loge, the Windows logo, YIi sdonis Media, and Your potential. Our passion ° are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Microsoft Corporation m the United States anJ`or other countries The names of actual companies and prooucts mentioned herein may be the trademark of their respective owners. www.americanradiohistory.com Billbearal JUNE 4, 2005 VOLUME 117, NO. 23 - t#411. ON THE CHARTS ALBUMS PAGE ARTIST / TITLE l'I'ItONT SYSTEM DE A DOWN / TOP 5 News BILLBOARD 200 56 MEZMERIZE AUSON KRAUSS + UNION STATION / 6 Washington -

HALLOWEEN MADNESS Events, Costume and Party Ideas to Scream About

October 27 - November 2, 2010 \ Volume 20 \ Issue 41 \ Always Free Film | Music | Culture HALLOWEEN MADNESS Events, Costume and Party Ideas to Scream About ©2010 CAMPUS CIRCLE • (323) 939-8477 • 5042 WILSHIRE BLVD., #600 LOS ANGELES, CA 90036 • WWW.CAMPUSCIRCLE.COM • ONE FREE COPY PER PERSON INVITE YOU AND A GUEST TO AN ADVANCE SCREENING OF THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 4 AT REGISTER FOR THIS SCREENING AT CAMPUSCIRCLE.COM/ SCREENING/ 127HOURS ALSO ENTER TO WIN A $100 GIFT CARD FROM REGISTER FOR THIS SWEEPSTAKES AT CAMPUSCIRCLE.COM/ SWEEPS/127HOURS SWEEPSTAKES ENDS ON 11/30. THIS FILM IS RATED R. RESTRICTED. Under 17 Requires Accompanying Parent Or Adult Guardian. Please note: Passes received through this promotion do not guarantee you a seat at the theatre. Seating is on a first-come, first-served basis, except for members of the reviewing press. Theatre is overbooked to ensure a full house. No admittance once screening has begun. All federal, state and local regulations apply. A recipient of tickets assumes any and all risks related to use of ticket, and accepts any restrictions required by ticket provider. Fox Searchlight Pictures, Campus Circle and their affiliates accept no responsibility or liability in connection with any loss or accident incurred in connection with use of a prize. Tickets cannot be exchanged, transferred or redeemed for cash, in whole or in part. We are not responsible if, for any reason, recipient is unable to use his/her ticket in whole or in part. All federal and local taxes are the responsibility of the winner. Void where prohibited by law. -

27 Colonna Sonora

PER INFORMAZIONI AGGIORNATE SU GIOCHI E DATE DI USCITA VISITA WWW.CODEMASTERS.COM Microsoft, Xbox, Xbox 360, Xbox LIVE e i loghi Xbox sono marchi del gruppo Microsoft. PRL08X3IT05 5024866342017 DiRT2_360_MAN_IT_v02.indd 1-2 6/8/09 16:18:01 DiRT2_360_MAN_IT_v02.indd 3 6/8/09 16:11:52 INDICE IL TOUR HA INIZIO 1 AL VOLANTE 3 IL MOTORHOME 5 TOUR DiRT 7 DISCIPLINE 10 VIAGGI NEL TEMPO, ECC. 12 I VEICOLI 13 TESTA A TESTA 15 CONTRO IL TEMPO 17 CONNETTERSI A XBOX LIVE 18 TORNEI 22 IMPOSTAZIONE VEICOLI 23 CREDITI 25 RINGRAZIAMENTI 26 COLONNA SONORA 27 LICENZA D’USO E GARANZIA 31 ASSISTENZA CLIENTI 32 DiRT2_360_MAN_IT_v02.indd 4 6/8/09 16:11:57 IL TOUR HA INIZIO Eccoci qui… questo potrebbe essere l’inizio di qualcosa di meraviglioso! Guarda… il mondo è là fuori, pronto per essere segnato da tracce di pneumatici. Questo è il tuo biglietto per il paradiso dell’automobilismo! Stai per affrontare il mondo, curva dopo curva. Non sarà facile, ma tieni questa guida a portata di mano e ce la farai. Inserisci la marcia, schiaccia l’acceleratore, e si parte... 1 DiRT2_360_MAN_IT_v02.indd 1 6/8/09 16:12:04 2 DiRT2_360_MAN_IT_v02.indd 2 6/8/09 16:12:09 AL VOLANTE Al centro di tutto c’è l’interazione fra uomo e vettura. È lì che si vincono o perdono le gare. Devi avere la sensibilità per comprendere come arrivare al limite, senza superarlo. E non smettere fi nché non oltrepassi la linea del traguardo. Nel menu Opzioni puoi personalizzare i comandi di gioco come preferisci. -

![714.01 [Cover] Mothernew3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2010/714-01-cover-mothernew3-7702010.webp)

714.01 [Cover] Mothernew3

CMJ NewMusic ® CMJ SIX FEET UNDER 2525 REVIEWED: MATES OF STATE, CMJ Report T. RAUMSHMIERE, DARKNESS, Issue No. 833 • September 29, 2003 • www.cmj.com SPOTLIGHT BELLE AND SEBASTIAN + MORE! CMJ WJUL’s students lost 25 hours of their weekly programming to a local newspaper. Can it happen to your station? CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2003 LAST CHANCE TO SAVE REGISTER BY OCT. 1! RETAIL THE UNIVERSAL ACCORDING TO RETAIL RADIO 200: WEEN MAKES IT A TRIPLE AT NO. 1 • SAVES THE DAY TAKES MOST ADDED NewMusic ® CMJ CMJCMJ Report 25 9/29/2003 Vice President & General Manager Issue No. 833 • Vol. 77 • No. 6 Mike Boyle CEDITORIALMJ COVER STORY Editor-In-Chief 6 Selling Out Kevin Boyce The University Of Massachusetts recently sold 25 hours of primetime programming on WJUL/Lowell, MA Associate Editors to a local newspaper to compensate for budget cuts. Ultimately, the decision was made in order to help Doug Levy the school raise it’s profile and increase enrollment, but by allowing a corporate entity into its midst, did CBradM MaybeJ the University Of Massachusetts open the door for other “media hungry” companies to take advantage of Louis Miller schools that could use the money and have a radio station at its disposal? CMJ investigates. Loud Rock Editor Amy Sciarretto DEPARTMENTS Jazz Editor 4 Essential/Reviews 23 Loud Rock Tad Hendrickson Reviews of Mates Of State, Belle And Read up on the latest releases from Ill Niño, RPM Editor Sebastian, David Bowie, T. Raumshmiere, The Burnt By The Sun and Between The Buried And Justin Kleinfeld Desert Sessions 9 And 10, the Darkness and Me; Madball signs a label deal; sneak a peak at Retail Editor Hero Pattern. -

Download Free Queens of the Stone Age Full Albums

download free queens of the stone age full albums . Like Clockwork. All the surface evidence on . Like Clockwork suggests Josh Homme is steering Queens of the Stone Age back to familiar territory. Once again, he's enlisted drummer Dave Grohl as his anchor and he's made amends with his erstwhile bassist Nick Oliveri, suggesting Homme is returning to either Rated R or Songs for the Deaf, the two turn-of-the-millennium masterpieces that thrust QOTSA out of their stoner rock cult, but . Like Clockwork isn't so simple as a return to roots. Homme flirts with his history as a way to make sense of his present, reconnecting with his strengths as a way to reorient himself, consolidating his indulgences and fancies into a record that obliterates middle-age malaise without taking a moment to pander to the past. Like always, Homme opens himself up to collaborations, wrangling an impressive roster that includes his wife Brody Dalle, his longtime companion Mark Lanegan, his protégé Arctic Monkey Alex Turner, his kindred spirit Trent Reznor, Scissor Sister Jake Shears, and superstar Elton John, but despite this large cast, the only musician who makes an indelible presence is Homme himself. Like Clockwork is unusually focused for a Queens of the Stone Age record, containing all of the group's hallmarks -- namely volume and crunch, but also a tantalizing sense of danger, finding seduction within the darkness -- but there is little of the desert sprawl and willful excess that have always distinguished their records. This is forceful, purposeful, fueled by dense interwoven riffs and colored with hints of piano and analog synthesizers that quite consciously evoke '70s future dystopia. -

Pre-Pedidos: 16 - Marzo - 2018

CLICK AQUÍ PARA VISITAR EL INDICE CON TODOS LOS LISTADOS DISPONIBLES descuento del 6% para pedidos de este listado recibidos hasta el 23 - marzo - 2018 inclusive PRE-PEDIDOS: 16 - MARZO - 2018 12.10 € CAPH DCP - MARBLED BEATS / PLUTO / FIZZY GLASSES / DROP THE RULES 11.37 € CAPH05 12" HOUSE BRG A1 A2 The 5th release from Caph comes from our good friend DCP. We hope you love it as much as we do B1 B2 12.00 € HIBIT SANTIERRI - PARK EP 11.28 € HR003 12" HOUSE GBR A1 A2 For the 3rd release we welcome upcoming Argentinian talent Santierri, who comes with 4 deep driving B1 house tracks filled with emotions and groove as you already expected B2 12.10 € LACONICA ALEX PERVUKHIN - SHIELD EP (KYIV RMX) 11.37 € LAC001 12" HOUSE / BROKEN / BREAKS UKR Laconic phrases are all about less words and more sense. We use the same principles in our stripped down A1 grooves which are released on fresh imprint - Laconica. Its all about minimalistic dance-floor tools which were tested in different clubs around the world, from Kyiv's 'Closer' to Concrete in Paris. For a debut EP, label founder Alex Pervukhin presents 3 different grooves. On the A-side you can find 'Hommie Groove', B1 which is an excellent example of a broken-beat house music with good-old airy Juno pads. On B side there are two 4/4 tools: 'BB', which could be heard in Varhat's mix for Concrete which was so hyped last year. 'AA' is a peak-time killer with analogue chords and jackin bassline. -

Temas Sin Identificar Inter Mayo – Agosto 2017 (Web)

track artist label isrc To U (Jack U (Feat. Alunageorge Dreams 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Tabtoo B.V ESA031429699 Oh La La La 2 Eivissa Lr Music USV291445858 Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Byte Records BEAA19505025 Get Ready 2 Unlimited Byte Records BEAA11301362 No Limit 2 Unlimited Xelon Entertainment BEAA19507007 Get Ready (Steve Aoki Extended) [Bonus Track] 2 Unlimited Xelon Entertainment (Under BEAA11301312 Get Ready (Steve Aoki Vocal Radio Edit) 2 Unlimited ARF841600030 Twilight Zone 2 Unlimited Byte Records Tribal Dance 2 Unlimited Byte Records BEAA10035015 No Limit (Extended No Rap) 2 Unlimited Xelon Entertainment BEAA10075003 Let The Beat Control Your Body 2 Unlimited Byte Records BEAA19505026 The Real Thing 2 Unlimited Xelonentertainment.Com BEAA19505031 Lick It 20 Fingers Unidisc Music Inc QM6N21492224 Asi Es Nuestro Amor 20-20 Lcr Entertainment, Inc. QM4TX1585456 Por Favor 24 Horas La Oreja Media Group. Inc USDXS1600145 Arabian Queen (A) 2Am Project West One Music GBFPN0302409 Gangsta'S Paradise 2Wei Position Music US43C1604320 Love Song 311 USMV20300285 Si Ya No Estás 3-2 Get Funky USUL10401636 Outro Feat. Mike B 380 Dat Lady USXQS1512615 On My Mind 3Lau Blume GBKPL1778912 Here Comes The Night 3Rd Force Higher Octave Music, Inc Forever Yours 3Rd Force Higher Octave Music, Inc Take Me Away (Into The Night) [Vocal Club Mix] 4 Strings NLC280210151 Missing 48Th St.Collective Music Brokers Window Shopper 50 Cent Feat. Murda Mase NLD910700619 Mambo N° 5 50 Essential Hits From The 50'S Rendez-Vous Digital FR0W61131618 Bullfight A Day To Remember Adtr Records USEP41609006 Paranoia A Day To Remember Adtr Records, Llc USEP41609001 The Downfall Of Us All A Day To Remember Victory Records USVIC0944801 All I Want A Day To Remember Victory Records USVIC1060302 Sukiyaki (2002 Digital Remaster) A Taste Of Honey USCA20101316 Sukiyaki (Remastered) A Taste Of Honey USCA29901300 Saturday Night A.M.P. -

*Med Reservation För Ändringar

*med reservation för ändringar Utg.dag Artist Titel Svensk Int'l Debutant Genre Label Bolag/Distributör Singel/Ep/Album Format - ange Informationstext Kontakt NAMN Kontakt E-POST Kontakt MOBIL CD, digitalt, vinyl 2016-06-01 Ben Mitkus Kills Me X Pop Virgin Capitol/Universal Singel Digitalt Ben Mitkus är Youtube-fenomenet som har frygt 200 000 Corinne Nystedt [email protected] 0739894385 följare och över 21 MILJONER visningar på sina videos. Han är dock inte bara en youtuber utan även artist och senast singeln Kills Me har hittills streamat 2 miljoner på Spotify. 2016-06-03 Ida Redig Du gamla du fria X Pop Capitol Capitol/Universal Singel Digitalt Ida Redig släpper idag Du gamla du fria. Det är en modern Peter Sundevall [email protected] 0708570507 version av Sveriges nationalsång och kvalar garanterat in som en av de starkaste inofficiella låtarna inför sommarens fotbolls-EM. 2016-06-03 Victor & Natten Vi var unga X Pop Capitol Capitol/Universal Singel Digitalt Victor & Natten medverkade i Melodifestivalen 2016 och Robert Olausson [email protected] 0706772520 släpper nu uppföljarsingeln. 2016-06-03 Dolly Style Unicorns and Ice-cream X Pop Capitol Capitol/Universal Singel Digitalt Supersuccétrion Dolly Style som tar alla kids i Sverige med Emma Nors [email protected] 0708604883 storm släpper nu in 5:e singel. CD+DVD, blu-ray, 2016-06-03 Rolling Stones Totally Stripped X Rock Eagle Vision Playground Music Album DVD Stones live unplugged Suzan Kverh [email protected] 070375 50 91 De senaste åren har han turnerat med giganter så som Lana Del Rey och Rufus Wainwright.