John Selden's History of Tithes in the Context of Two of His Other Early Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America

P1: IwX/KaD 0521827450agg.xml CY395B/Ward 0 521 82745 0 May 7, 2004 7:37 The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America LEE WARD Campion College University of Regina iii P1: IwX/KaD 0521827450agg.xml CY395B/Ward 0 521 82745 0 May 7, 2004 7:37 published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Lee Ward 2004 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/12 pt. System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Ward, Lee, 1970– The politics of liberty in England and revolutionary America / Lee Ward p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. isbn 0-521-82745-0 1. Political science – Great Britain – Philosophy – History – 17th century. 2. Political science – Great Britain – Philosophy – History – 18th century. 3. Political science – United States – Philosophy – History – 17th century. 4. Political science – United States – Philosophy – History – 18th century. 5. United States – History – Revolution, 1775–1783 – Causes. -

JAMES USSHER Copyright Material: Irish Manuscripts Commission

U3-030215 qxd.qxd:NEW USH3 3/2/15 11:20 Page i The Correspondence of JAMES USSHER Copyright material: Irish Manuscripts Commission Commission Manuscripts Irish material: Copyright U3-030215 qxd.qxd:NEW USH3 3/2/15 11:20 Page iii The Correspondence of JAMES USSHER 1600–1656 V O L U M E I I I 1640–1656 Commission Letters no. 475–680 editedManuscripts by Elizabethanne Boran Irish with Latin and Greek translations by David Money material: Copyright IRISH MANUSCRIPTS COMMISSION 2015 U3-030215 qxd.qxd:NEW USH3 3/2/15 11:20 Page iv For Gertie, Orla and Rosemary — one each. Published by Irish Manuscripts Commission 45 Merrion Square Dublin 2 Ireland www.irishmanuscripts.ie Commission Copyright © Irish Manuscripts Commission 2015 Elizabethanne Boran has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright and Related Rights Act 2000, Section 107. Manuscripts ISBN 978-1-874280-89-7 (3 volume set) Irish No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. The index was completed with the support of the Arts andmaterial: Social Sciences Benefaction Fund, Trinity College, Dublin. Copyright Typeset by December Publications in Adobe Garamond and Times New Roman Printed by Brunswick Press Index prepared by Steve Flanders U3-030215 qxd.qxd:NEW USH3 3/2/15 11:20 Page v S E R I E S C O N T E N T S V O L U M E I Abbreviations xxv Acknowledgements xxix Introduction xxxi Correspondence of James Ussher: Letters no. -

Satirical Legal Studies: from the Legists to the Lizard

Michigan Law Review Volume 103 Issue 3 2004 Satirical Legal Studies: From the Legists to the Lizard Peter Goodrich Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation Peter Goodrich, Satirical Legal Studies: From the Legists to the Lizard, 103 MICH. L. REV. 397 (2004). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol103/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SATIRICAL LEGAL STUDIES: FROM THE LEGISTS TO THE LIZARD Peter Goodrich* ANALYTICAL TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................... .............................................. ........ .... ..... ..... 399 I. FRAGMENTA ANTIQUITATIS (THE ENDURING TRADITION) .. 415 A. The Civilian Tradition .......................................................... 416 B. The Sermon on the Laws ......................... ............................. 419 C. Satirical Themes ....................... ............................................. 422 1. Personification .... ............................................................. 422 2. Novelty ....................................... -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

No. 16-1466 In the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit KEVIN BROTT; KATHALEEN BONDON; LOUIS CHURCHWELL; PHARQUIETTE CHURCHWELL; FREDRICKS CONSTRUCTION COMPANY; KAREN FRISCO; PATRICIA GREEN; VERONICA HARWELL-SMITH; RICKEY HOLDEN; CAROLYN HOLDEN; ROBERT JONES; JEREMY KEITH; JOEL F. KOWALSKI; SHARON KOWALSKI; THERESA LOPEZ; ILEINE MAXIN; THOMASINE MESHAWBOOSE; THOMAS NAVARINI; LUIS SANTILLANES; YOLANDA SANTILLANES; WESTSHORE ENGINEERING & SURVEYING, INCORPORATED; 2017 8TH, LLC; 2170 SHERMAN, LLC, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Defendant-Appellee. _______________________________________ Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western District of Michigan at Grand Rapids, No. 1:15-cv-00038. The Honorable Janet T. Neff, Judge Presiding. BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS MARK F. (THOR) HEARNE II MATTHEW L. VICARI MEGHAN S. LARGENT STEPHEN J. VAN STEMPVOORT STEPHEN S. DAVIS MILLER, JOHNSON, SNELL & ARENT FOX LLP CUMMISKEY, P.L.C. 1717 K Street, NW 45 Ottawa Ave. SW, Suite 1100 Washington, DC 20006 Grand Rapids, MI 49503 (202) 857-6000 (616) 831-1700 Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants COUNSEL PRESS ∙ (866) 703-9373 PRINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER Case: 16-1466 Document: 10 Filed: 04/28/2016 Page: 1 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT Disclosure of Corporate Affiliations and Financial Interest Sixth Circuit Case Number: 16-1466 Case Name: Brott, et al. v. United States Name of counsel: Mark F. (Thor) Hearne, II Pursuant to 6th Cir. R. 26.1, Kevin Brott, et al. Name of Party makes the following disclosure: 1. Is said party a subsidiary or affiliate of a publicly owned corporation? If Yes, list below the identity of the parent corporation or affiliate and the relationship between it and the named party: No. -

The English Civil Wars a Beginner’S Guide

The English Civil Wars A Beginner’s Guide Patrick Little A Oneworld Paperback Original Published in North America, Great Britain and Australia by Oneworld Publications, 2014 Copyright © Patrick Little 2014 The moral right of Patrick Little to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him/her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 9781780743318 eISBN 9781780743325 Typeset by Siliconchips Services Ltd, UK Printed and bound in Denmark by Nørhaven A/S Oneworld Publications 10 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3SR England Stay up to date with the latest books, special offers, and exclusive content from Oneworld with our monthly newsletter Sign up on our website www.oneworld-publications.com Contents Preface vii Map of the English Civil Wars, 1642–51 ix 1 The outbreak of war 1 2 ‘This war without an enemy’: the first civil war, 1642–6 17 3 The search for settlement, 1646–9 34 4 The commonwealth, 1649–51 48 5 The armies 66 6 The generals 82 7 Politics 98 8 Religion 113 9 War and society 126 10 Legacy 141 Timeline 150 Further reading 153 Index 157 Preface In writing this book, I had two primary aims. The first was to produce a concise, accessible account of the conflicts collectively known as the English Civil Wars. The second was to try to give the reader some idea of what it was like to live through that trau- matic episode. -

The Political Views and Parliamentary Career of John Selden J.T

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 3-3-1995 The political views and Parliamentary career of John Selden J.T. Price Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Price, J.T., "The political views and Parliamentary career of John Selden" (1995). Honors Theses. Paper 710. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Richmond The Political Views and Parliamentary Career of John Selden J. T. Price Senior Honors Thesis Department of History Dr. John R. Rilling March 3, 1995 John Selden rose from a relatively obscure background to become an internationally renowned legal scholar and a key parliamentary leader during the contentious Parliament of 1628-1629. Selden's father was a "ministrell," yet the younger Selden became one of the most respected thinkers in London while still fairly young, and would eventually take a leading role in Parliament. 1 Selden's brilliant mind, personality, and actions as an "honest broker" in his turbulent times made him a man who all sides could respect and who could stay afloat and prosper in the shifting political sands of Seventeenth Century England. John Selden was the son of a minstrel who married Margaret Baker~ the daughter of a Kentish squire. -

Common Law Judicial Office, Sovereignty, and the Church Of

1 Common Law Judicial Office, Sovereignty, and the Church of England in Restoration England, 1660-1688 David Kearns Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney A thesis submitted to fulfil requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 2 This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. David Kearns 29/06/2019 3 Authorship Attribution Statement This thesis contains material published in David Kearns, ‘Sovereignty and Common Law Judicial Office in Taylor’s Case (1675)’, Law and History Review, 37:2 (2019), 397-429, and material to be published in David Kearns and Ryan Walter, ‘Office, Political Theory, and the Political Theorist’, The Historical Journal (forthcoming). The research for these articles was undertaken as part of the research for this thesis. I am the sole author of the first article and sole author of section I of the co-authored article, and it is the research underpinning section I that appears in the thesis. David Kearns 29/06/2019 As supervisor for the candidature upon which this thesis is based, I can confirm that the authorship attribution statements above are correct. Andrew Fitzmaurice 29/06/2019 4 Acknowledgements Many debts have been incurred in the writing of this thesis, and these acknowledgements must necessarily be a poor repayment for the assistance that has made it possible. -

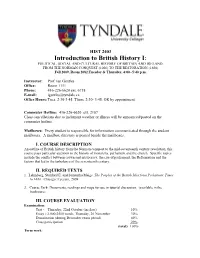

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

Cromwellian Anger Was the Passage in 1650 of Repressive Friends'

Cromwelliana The Journal of 2003 'l'ho Crom\\'.Oll Alloooluthm CROMWELLIANA 2003 l'rcoklcnt: Dl' llAlUW CO\l(IA1© l"hD, t'Rl-llmS 1 Editor Jane A. Mills Vice l'l'csidcnts: Right HM Mlchncl l1'oe>t1 l'C Profcssot·JONN MOlUUU.., Dl,llll, F.13A, FlU-IistS Consultant Peter Gaunt Professor lVAN ROOTS, MA, l~S.A, FlU~listS Professor AUSTIN WOOLll'YCH. MA, Dlitt, FBA CONTENTS Professor BLAIR WORDEN, FBA PAT BARNES AGM Lecture 2003. TREWIN COPPLESTON, FRGS By Dr Barry Coward 2 Right Hon FRANK DOBSON, MF Chairman: Dr PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS 350 Years On: Cromwell and the Long Parliament. Honorary Secretary: MICHAEL BYRD By Professor Blair Worden 16 5 Town Farm Close, Pinchbeck, near Spalding, Lincolnshire, PEl 1 3SG Learning the Ropes in 'His Own Fields': Cromwell's Early Sieges in the East Honorary Treasurer: DAVID SMITH Midlands. 3 Bowgrave Copse, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 2NL By Dr Peter Gaunt 27 THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION was founded in 1935 by the late Rt Hon Writings and Sources VI. Durham University: 'A Pious and laudable work'. By Jane A Mills · Isaac Foot and others to commemorate Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan 40 statesman, and to encourage the study of the history of his times, his achievements and influence. It is neither political nor sectarian, its aims being The Revolutionary Navy, 1648-1654. essentially historical. The Association seeks to advance its aims in a variety of By Professor Bernard Capp 47 ways, which have included: 'Ancient and Familiar Neighbours': England and Holland on the eve of the a. -

Anglo-Saxons and English Identity

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Anna Šerbaumová Anglo-Saxons and English Identity Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Dr., M.A. Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph. D. 2010 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. V Plzni dne 22.11.2010 …………………………………………… I would like to thank my supervisor Dr., M.A. Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. for his advice and comments, and my family and boyfriend for their constant support. Table of Contents 0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1 Anglo-Saxon Period (410–1066) ........................................................................................... 4 1.1 Anglo-Saxon Settlement in Britain ................................................................................ 4 1.2 A Brief History of the Anglo-Saxon Period ................................................................... 5 1.3 ―Saxons‖,― English‖ or ―Anglo-Saxons‖? ..................................................................... 7 1.4 The Origins of English Identity and the Venerable Bede .............................................. 9 1.5 English Identity in the Ninth Century and Alfred the Great‘s Preface to the Pastoral Care ...................................................................................................... 15 1.6 Conclusion .................................................................................................................. -

Cromwelliana

CROMWELLIANA Published by The Cromwell Association, a registered charity, this Cromwelliana annual journal of Civil War and Cromwellian studies contains articles, book reviews, a bibliography and other comments, contributions and III Series papers. Details of availability and prices of both this edition and previous editions of Cromwelliana are available on our website: The Journal of www.olivercromwell.org. The 2018 Cromwelliana Cromwell Association The Cr The omwell Association omwell No 1 ‘promoting our understanding of the 17th century’ 2018 The Cromwell Association The Cromwell Museum 01480 708008 Grammar School Walk President: Professor PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS Huntingdon www.cromwellmuseum.org PE29 3LF Vice Presidents: PAT BARNES Rt Hon FRANK DOBSON, PC Rt Hon STEPHEN DORRELL, PC The Cromwell Museum is in the former Huntingdon Grammar School Dr PATRICK LITTLE, PhD, FRHistS where Cromwell received his early education. The Cromwell Trust and Professor JOHN MORRILL, DPhil, FBA, FRHistS Museum are dedicated to preserving and communicating the assets, legacy Rt Hon the LORD NASEBY, PC and times of Oliver Cromwell. In addition to the permanent collection the Dr STEPHEN K. ROBERTS, PhD, FSA, FRHistS museum has a programme of changing temporary exhibitions and activities. Professor BLAIR WORDEN, FBA Opening times Chairman: JOHN GOLDSMITH Honorary Secretary: JOHN NEWLAND April – October Honorary Treasurer: GEOFFREY BUSH Membership Officer PAUL ROBBINS 11.00am – 3.30pm, Tuesday – Sunday The Cromwell Association was formed in 1937 and is a registered charity (reg no. November – March 1132954). The purpose of the Association is to advance the education of the public 1.30pm – 3.30pm, Tuesday – Sunday (11.00am – 3.30pm Saturday) in both the life and legacy of Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658), politician, soldier and statesman, and the wider history of the seventeenth century.