The Mongolian Naval Expedition to Java in the 13Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concise Ancient History of Indonesia.Pdf

CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY OF INDONESIA CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY O F INDONESIA BY SATYAWATI SULEIMAN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION JAKARTA Copyright by The Archaeological Foundation ]or The National Archaeological Institute 1974 Sponsored by The Ford Foundation Printed by Djambatan — Jakarta Percetakan Endang CONTENTS Preface • • VI I. The Prehistory of Indonesia 1 Early man ; The Foodgathering Stage or Palaeolithic ; The Developed Stage of Foodgathering or Epi-Palaeo- lithic ; The Foodproducing Stage or Neolithic ; The Stage of Craftsmanship or The Early Metal Stage. II. The first contacts with Hinduism and Buddhism 10 III. The first inscriptions 14 IV. Sumatra — The rise of Srivijaya 16 V. Sanjayas and Shailendras 19 VI. Shailendras in Sumatra • •.. 23 VII. Java from 860 A.D. to the 12th century • • 27 VIII. Singhasari • • 30 IX. Majapahit 33 X. The Nusantara : The other islands 38 West Java ; Bali ; Sumatra ; Kalimantan. Bibliography 52 V PREFACE This book is intended to serve as a framework for the ancient history of Indonesia in a concise form. Published for the first time more than a decade ago as a booklet in a modest cyclostyled shape by the Cultural Department of the Indonesian Embassy in India, it has been revised several times in Jakarta in the same form to keep up to date with new discoveries and current theories. Since it seemed to have filled a need felt by foreigners as well as Indonesians to obtain an elementary knowledge of Indonesia's past, it has been thought wise to publish it now in a printed form with the aim to reach a larger public than before. -

A Short History of Indonesia: the Unlikely Nation?

History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page i A SHORT HISTORY OF INDONESIA History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page ii Short History of Asia Series Series Editor: Milton Osborne Milton Osborne has had an association with the Asian region for over 40 years as an academic, public servant and independent writer. He is the author of eight books on Asian topics, including Southeast Asia: An Introductory History, first published in 1979 and now in its eighth edition, and, most recently, The Mekong: Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future, published in 2000. History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page iii A SHORT HISTORY OF INDONESIA THE UNLIKELY NATION? Colin Brown History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page iv First published in 2003 Copyright © Colin Brown 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Allen & Unwin 83 Alexander Street Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100 Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Brown, Colin, A short history of Indonesia : the unlikely nation? Bibliography. -

Historical Game of Majapahit Kingdom Based on Tactical Role-Playing Game

Historical Game of Majapahit Kingdom based on Tactical Role-playing Game Mohammad Fadly Syahputra, Muhammad Kurniawan Widhianto and Romi Fadillah Rahmat Department Information Technology, Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology, University of Sumatera Utara, Medan, Indonesia Keywords: Cut-out Animation, History, Majapahit, Role-playing Game, Tactical Role-playing Game, Turn based Strategy, Video Game. Abstract: Majapahit was a kingdom centered in East Java, which once stood around year 1293 to 1500 C. Majapahit kingdom was the last Hindu-Buddhist kingdom that controlled Nusantara and is regarded as one of the greatest kingdom in Indonesia. The lack of modern entertainment content about the history of Majapahit kingdom made historical subject become less attractive. Therefore, we need a modern entertainment as one option to learn about the fascinating history of the kingdom of Majapahit. In this study the authors designed a video game about history of Majapahit kingdom with the genre of tactical role-playing game. Tactical role-playing game is a sub genre of role playing game by using system of turn-based strategy in every battle. In tactical role-playing game, players will take turns with the opponent and can only take action in their turn and each character will have an attribute and level as in role-playing game video game. This study used the A* algorithm to determine the movement direction of the unit and cut-out techniques in the making of animation. This study demonstrated that video games can be used as a media to learn about history. 1 INTRODUCTION only used as an entertainment, but also can be used as a story telling, and sometimes game also can be mixed Majapahit was a kingdom centered in East Java, with educational elements to train someone. -

Historical Scholarship Between South Asia and Europe

Java’s Mongol Demon. Inscribing the Horse Archer into the Epic History of Majapahit1 Jos Gommans Abstract The temple of Panataran near Blitar in Java features a unique scene in which one of the Ramayana demons, Indrajit, is depicted as a Mongol mounted horse-warrior. This essay explores the meaning of this representation on the basis of the multi- layered history and historiography of Java’s Mongol invasion. “Everything that happened in the Ramayana was absolutely real.” Maheshvaratirtha, sixteenth century (cited in Pollock 1993: 279) Panataran Temple Walking anti-clockwise around the base of the main terrace at Panataran Tem- ple, twelve kilometres north-east of Blitar in Java, the visitor is treated to the truly remarkable display of 106 relief panels carved with sequential scenes from the story of the Ramayana – the source of this particular series is the Kakawin version, which almost certainly dates from the ninth century CE, making it the earliest surviving work of Old Javanese poetry. Interestingly, the main charac- ter in this pictorial rendering is not the more customary figure of Rama, the exiled king, but instead his loyal monkey companion Hanuman. However, given the popularity of Hanuman in the Indic world in around the time the Panataran panels were made – the mid-fourteenth century – his prominence is perhaps not all that surprising after all (Lutgendorf 2007). Except for Hanu- man’s unusual role, the panels follow the conventional narrative, starting with the abduction of Rama’s wife Sita by Ravana, the demon king of Lanka. Many of the panels depict Hanuman’s heroic fights with demons (rakshasas), and the first series of battles culminates in panel 55, which shows Hanuman being attacked by Ravana’s son Indrajit. -

Round 3 Bowl Round 3 First Quarter

NHBB A-Set Bowl 2016-2017 Bowl Round 3 Bowl Round 3 First Quarter (1) This author of Postcards from the Edge wrote multiple autobiographical works that openly discuss her positive experience with electroconvulsive therapy as treatment for bipolar disorder. This author of the memoir The Princess Diarist is, with her mother, the subject of Bright Lights, a documentary that premiered on HBO in January 2017, just weeks after their deaths. For ten points, name this mental health advocate, daughter of Debbie Reynolds, and actress who portrayed Princess Leia in the Star Wars films. ANSWER: Carrie Fisher (2) Oscar L´opez Rivera, an independence activist for this territory, had his prison sentence commuted during Barack Obama's last week in office. In 2016, this territory was blocked from declaring bankruptcy by the Supreme Court. Like Guam and the Philippines, this commonwealth's ownership transferred to the U.S. after the Spanish-American War. For ten points, name this Caribbean island territory where activists in its capital, San Juan, wish to become the 51st U.S. state. ANSWER: Puerto Rico (3) These people discovered a \land of stone slabs" that might be the Torngat Mountains. These people harvested lumber from Markland and recorded finding grapes in another area. These people battled against Skraelings and found grapes during their brief settlements in Vinland and at L'Anse Aux Meadows. The first European peoples to land in Canada were, for ten points, what Scandinavians, including the explorer Leif Ericsson? ANSWER: Norsemen (or Vikings; accept Danes or Greenlanders; prompt on Scandinavians before mentioned) (4) This group regularly held meetings at the Menger Hotel Bar of San Antonio. -

BAB II DESKRIPSI OBYEK PENELITIAN A. Dari Singasari

BAB II DESKRIPSI OBYEK PENELITIAN A. Dari Singasari Sampai PIM Sejarah singkat berdirinya kerajaan Majapahit, penulis rangkum dari berbagai sumber. Kebanyakan dari literatur soal Majapahit adalah hasil tafsir, interpretasi dari orang per orang yang bisa jadi menimbulkan sanggahan di sana- sini. Itulah yang penulis temui pada forum obrolan di dunia maya seputar Majapahit. Masing-masing pihak merasa pemahamannyalah yang paling sempurna. Maka dari itu, penulis mencoba untuk merangkum dari berbagai sumber, memilih yang sekiranya sama pada setiap perbedaan pandangan yang ada. Keberadaan Majapahit tidak bisa dilepaskan dari kerajaan Singasari. Tidak hanya karena urutan waktu, tapi juga penguasa Majapahit adalah para penguasa kerajaan Singasari yang runtuh akibat serangan dari kerajaan Daha.1 Raden Wijaya yang merupakan panglima perang Singasari kemudian memutuskan untuk mengabdi pada Daha di bawah kepemimpinan Jayakatwang. Berkat pengabdiannya pada Daha, Raden Wijaya akhirnya mendapat kepercayaan penuh dari Jayakatwang. Bermodal kepercayaan itulah, pada tahun 1292 Raden Wijaya meminta izin kepada Jayakatwang untuk membuka hutan Tarik untuk dijadikan desa guna menjadi pertahanan terdepan yang melindungi Daha.2 Setelah mendapat izin Jayakatwang, Raden Wijaya kemudian membabat hutan Tarik itu, membangun desa yang kemudian diberi nama Majapahit. Nama 1 Esa Damar Pinuluh, Pesona Majapahit (Jogjakarta: BukuBiru, 2010), hal. 7-14. 2 Ibid., hal. 16. 29 Majapahit konon diambil dari nama pohon buah maja yang rasa buahnya sangat pahit. Kemampuan Raden Wijaya sebagai panglima memang tidak diragukan. Sesaat setelah membuka hutan Tarik, tepatnya tahun 1293, ia menggulingkan Jayakatwang dan menjadi raja pertama Majapahit. Perjalanan Majapahit kemudian diwarnai dengan beragam pemberontakan yang dilakukan oleh para sahabatnya yang merasa tidak puas atas pembagian kekuasaannya. Sekali lagi Raden Wijaya membuktikan keampuhannya sebagai seorang pemimpin. -

Gotong Royong: a Study of an Indonesian Concept and the Application of Its Principles to the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Indonesia

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 1975 Gotong Royong: A Study Of An Indonesian Concept And The Application Of Its Principles To The Seventh-Day Adventist Church In Indonesia Jan Manaek Hutauruk Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Hutauruk, Jan Manaek, "Gotong Royong: A Study Of An Indonesian Concept And The Application Of Its Principles To The Seventh-Day Adventist Church In Indonesia" (1975). Dissertation Projects DMin. 354. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/354 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary GOTONG ROYONG: A STUDY OF AN INDONESIAN CONCEPT AND THE APPLICATION OF ITS PRINCIPLES TO THE SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH IN INDONESIA A Project Report Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Ministry by Jan Manaek Hutauruk March 1975 Approval ACKNOWLEDGEMENT A work of this kind is a work of dependence. Without the support of several important people this study would have been impossible. Truly what the author has accomplished is the result of gotong royong— a group work. Dr. Gottfried Oosterwal has given the author guidance, advice, and encouragement; Dr. Robert Johnston has read the paper through and given his criticism to improve it; Dr. -

Appendix Appendix

APPENDIX APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS, WITH GOVERNORS AND GOVERNORS-GENERAL Burma and Arakan: A. Rulers of Pagan before 1044 B. The Pagan dynasty, 1044-1287 C. Myinsaing and Pinya, 1298-1364 D. Sagaing, 1315-64 E. Ava, 1364-1555 F. The Toungoo dynasty, 1486-1752 G. The Alaungpaya or Konbaung dynasty, 1752- 1885 H. Mon rulers of Hanthawaddy (Pegu) I. Arakan Cambodia: A. Funan B. Chenla C. The Angkor monarchy D. The post-Angkor period Champa: A. Linyi B. Champa Indonesia and Malaya: A. Java, Pre-Muslim period B. Java, Muslim period C. Malacca D. Acheh (Achin) E. Governors-General of the Netherlands East Indies Tai Dynasties: A. Sukhot'ai B. Ayut'ia C. Bangkok D. Muong Swa E. Lang Chang F. Vien Chang (Vientiane) G. Luang Prabang 954 APPENDIX 955 Vietnam: A. The Hong-Bang, 2879-258 B.c. B. The Thuc, 257-208 B.C. C. The Trieu, 207-I I I B.C. D. The Earlier Li, A.D. 544-602 E. The Ngo, 939-54 F. The Dinh, 968-79 G. The Earlier Le, 980-I009 H. The Later Li, I009-I225 I. The Tran, 1225-I400 J. The Ho, I400-I407 K. The restored Tran, I407-I8 L. The Later Le, I4I8-I8o4 M. The Mac, I527-I677 N. The Trinh, I539-I787 0. The Tay-Son, I778-I8o2 P. The Nguyen Q. Governors and governors-general of French Indo China APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS BURMA AND ARAKAN A. RULERS OF PAGAN BEFORE IOH (According to the Burmese chronicles) dat~ of accusion 1. Pyusawti 167 2. Timinyi, son of I 242 3· Yimminpaik, son of 2 299 4· Paikthili, son of 3 . -

Gayatri Dalam Sejarah Singhasari Dan Majapahit1

16 SEJARAH DAN BUDAYA, Tahun Ketujuh, Nomor 2, Desember 2013 GAYATRI DALAM SEJARAH SINGHASARI DAN MAJAPAHIT1 Deny Yudo Wahyudi1 Jurusan Sejarah FIS Universitas Negeri Malang Abstrak: Gayatri is an important woman figure in history of Majapahit. As a main family member, she had central role, although her role is invisible. Her status as Rajapatni gave her a big power, so she ascended her husband’s throne after her son in law, who has no son, died. Her Pendharmaan becomes an important source to be studied because of its vague of supporting data. Key Words: Gayatri, history, Singhasari, Majapahit Pergulatan menarik ditunjukkan Prof. Drake Singhasari sebagai pendahulu raja-raja (mantan Diplomat Canada) ketika akan Majapahit. Sumber lain selama ini hanya memilih tema tulisan sejarah sebagai kebiasa- Pararaton dan Nagarakartagama. Informasi an beliau ketika bertugas di luar negeri. yang diberikan oleh Mula-Malurung banyak Pilihan terhadap sosok Gayatri sebagai bahan yang memperkuat atau bahkan memperjelas tulisan patut diacungi ibu jari karena beliau kisah dalam Pararaton, karena tidak semua tidak tergoda untuk mengangkat nama-nama hal kisah dalam Pararton tergambarkan besar dalam sejarah Majapahit, semisal Prabu dengan jelas dan justru beberapa menimbul- Wijaya, Hayam Wuruk, Patih Gajah Mada kan pertanyaan. ataupun kalau tokoh wanita, Tribhuana dan Silsilah raja-raja Singhasari me- Suhita yang lebih banyak perannya dalam nunjukkan bahwa semua cabang dalam sejarah kerajaan. Selanjutnya saya akan keluarga ini pernah memerintah3 dalam tahta sedikit berdiskusi dengan tulisan Prof. Drake Singhasari. Hal yang menarik bahwa politik melalui tulisan sederhana, karena jika me- perkawinan selain sebagai upaya konsolidasi lakuklan kontra tulisan memerlukan waktu dan meredam suksesi juga dapat berakibat panjang untuk mempersiapkan suatu proses berlawanan, yaitu penuntutan hak atas tahta. -

The Dawn of American Cryptology, 1900–1917

United States Cryptologic History The Dawn of American Cryptology, 1900–1917 Special Series | Volume 7 Center for Cryptologic History David Hatch is technical director of the Center for Cryptologic History (CCH) and is also the NSA Historian. He has worked in the CCH since 1990. From October 1988 to February 1990, he was a legislative staff officer in the NSA Legislative Affairs Office. Previously, he served as a Congressional Fellow. He earned a B.A. degree in East Asian languages and literature and an M.A. in East Asian studies, both from Indiana University at Bloomington. Dr. Hatch holds a Ph.D. in international relations from American University. This publication presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other US government entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please email [email protected] or write to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755 Cover: Before and during World War I, the United States Army maintained intercept sites along the Mexican border to monitor the Mexican Revolution. Many of the intercept sites consisted of radio-mounted trucks, known as Radio Tractor Units (RTUs). Here, the staff of RTU 33, commanded by Lieutenant Main, on left, pose for a photograph on the US-Mexican border (n.d.). United States Cryptologic History Special Series | Volume 7 The Dawn of American Cryptology, 1900–1917 David A. -

Profil Budaya Dan Bahasa Kabupaten Malang Provinsi Jawa Timur

KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN SEKRETARIAT JENDERAL PUSAT DATA DAN TEKNOLOGI INFORMASI PROFIL BUDAYA DAN BAHASA KAB. MALANG PROVINSI JAWA TIMUR PROFIL BUDAYA DAN BAHASA KABUPATEN MALANG PROVINSI JAWA TIMUR KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN PUSAT DATA DAN TEKNOLOGI INFORMASI TANGERANG SELATAN, 2020 Profil Budaya dan Bahasa Kab. Malang Provinsi Jawa Timur Diterbitkan Pusat Data dan Teknologi Informasi Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Gedung Grha Tama, Lantai 4 Jl. R.E. Martadinata, Ciputat, Tangerang Selatan Pengarah: Dr. Budi Purwaka, S.E., M.M. Editor: Dr. Dwi Winanto Hadi, M.Pd. Penyusun Naskah: Lauda Septiana, S.Si. Desainer Grafis: Hendri Syam, S.T. Cetakan pertama, ISBN: 978-602-8449-60-1 2020 Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Hak cipta dilindungi Undang-Undang All rights reserved. Dilarang memperbanyak buku ini dalam bentuk dan cara apapun tanpa izin tertulis dari penerbit. Profil Budaya dan Bahasa Kabupaten Malang Provinsi Jawa Timur iIi Kata Pengantar Penyusunan profil ini dilakukan berdasarkan hasil verifikasi dan validasi data kebudayaan dan kebahasaan di wilayah Kabupaten Malang, Provinsi Jawa Timur dalam rangka terwujudnya output layanan data dan informasi di Pusat Data dan Teknologi Informasi, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan. Selain itu, data yang disajikan bersumber dari Balai Pelestarian Cagar Budaya Provinsi Jawa Timur, Balai Pelestarian Nilai Budaya D. I. Yogyakarta, serta Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa. Profil ini menguraikan kekayaan dan keragaman budaya Kabupaten Malang baik dari segi warisan budaya benda, warisan budaya tak benda dan bahasa. Hal ini bertujuan agar data kebudayaan dan kebahasaan dapat lebih berdaya guna dan berhasil guna untuk mendukung pelaksanaan pemajuan kebudayaan, yaitu untuk melindungi, memanfaatkan, dan mengembangkan kebudayaan Indonesia. -

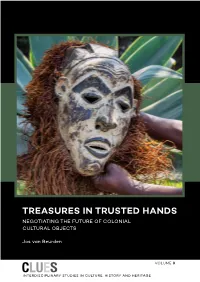

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art.