Dear Colleagues, Please Find Below the Mainstream News on Haiti For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

United Nations CEDAW/C/HTI/7 Convention on the Elimination Distr.: General of All Forms of Discrimination 9 July 2008 English against Women Original: French Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women Combined initial, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh periodic reports of States parties Haiti* * The present report is being issued without formal editing. 08-41624 (E) 090708 050908 *0841624* CEDAW/C/HTI/7 LIBERTY EQUALITY FRATERNITY REPUBLIC OF HAITI Implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women CEDAW COMBINED REPORTS 1982, 1986, l990, 1994, 1998, 2002 and 2006 Port-au-Prince March 2008 2 08-41624 CEDAW/C/HTI/7 FOREWORD On behalf of the Republic of Haiti, I am proud to present in the pages that follow the reports on implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. The Convention was ratified in 1981 and, pursuant to article 18 of that same Convention, the Government of Haiti should have submitted an initial implementation report one year after ratification and another every four years thereafter. To compensate for failure to produce those reports, starting in April 2006 the Ministry for the Status of Women and Women’s Rights stepped up its activities and embarked on the process of preparing the report. That report is of the utmost importance to the Haitian State. It enables it to evaluate and systematize progress made with respect to women’s rights and to establish priorities for the future. -

Mathilde Pierre Weak Judicial Systems And

Mathilde Pierre Weak Judicial Systems and Systematic Sexual Violence against Women and Girls: The Socially Constructed Vulnerability of Female Bodies in Haiti This thesis has been submitted on this day of April 16, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the degree requirements for the NYU Global Liberal Studies Bachelor of Arts degree. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor Emily Bauman, who has guided me through every step in the year-long process of writing my thesis. The time and energy she invested in thoroughly reading and commenting on my work, in recommending other avenues of further research, and in pushing me to deepen my analysis were truly invaluable. I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Joyce Apsel who, although abroad in Florence, Italy, set aside time to speak with me over Skype, to comment on my rough draft, and to advise me on the approach of my argument in my thesis. I would additionally like to thank all of the individuals who set aside considerable time to meet with me for interviews in Port-au-Prince, most notably Attorney Claudy Gassant, Attorney Rosy Auguste, Attorney Marie Alice Belisaire, Attorney Giovanna Menard, Judge Jean Wilner Morin, Carol Pierre-Paul Jacob, Marie Yolaine Gilles, and Officer Guerson Joseph. Finally I extend a heartfelt thank you to my parents, Mathias and Gaëlle Pierre, who greatly assisted in connecting me with the individuals I interviewed and whose constant support and encouragement helped me to push through in the completion of my thesis. 1 ABSTRACT Widespread sexual violence against women and girls in Haiti is a phenomenon that largely persists due to a failure to prosecute male perpetrators and enforce the domestic and international laws that exist to criminalize rape. -

BEYOND-SHOCK-Nov-2012-Report-On-GBV-Progress

BEYOND SHOCK Charting the landscape of sexual violence in post-quake Haiti: Progress, Challenges & Emerging Trends 2010-2012 Anne-christine d’Adesky with PotoFanm+Fi Foreword by Edwidge Danticat | Photo essay by Nadia Todres November 2012 www.potofi.org | www.potofanm.org Report Sponsors: Trocaire, World Pulse & Tides Beyond Shock report 11.26 ABRIDGED VERSION (SHORT REPORT) Author: Anne‐christine d’Adesky and the PotoFanm+Fi coalition © PotoFanm+Fi November 2012. All Rights Reserved. www.potofanm.org For information, media inquiries, report copies: Contact: Anne‐christine d’Adesky Report Coordinator, PotoFanm+Fi Email: [email protected] Haiti: +508 | 3438 2315 US: (415) 690‐6199 1 Beyond Shock DEDICATION This report is dedicated to Haitians who are victims of crimes of sexual violence, including those affected after the historic 2010 earthquake. Some died of injuries related to these crimes. Others have committed suicide, unable to bear injustice and further suffering. May they rest in peace. May we continue to seek justice in their names. Let their memory serve as a reminder of the sacredness of every human life and the moral necessity to act with all our means to protect it. It is also dedicated to the survivors who have had the courage to step out of the shadows of shock, pain, suffering, indignity, and silence and into recovery and public advocacy. Their voices guide a growing grassroots movement. We also acknowledge and thank the many individuals and groups in and outside Haiti – community activists, political leaders, health providers, police officers, lawyers, judges, witnesses, caretakers and family members, human rights and gender activists, journalists and educators – who carry the torch. -

Urban Informality, Post-Disaster Management, and Challenges to Gender-Responsive Planning in Haiti Since the 2010 Earthquake

Research Article Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud Volume 5 Issue 5 - September 2020 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Edad Mercier DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2020.05.555675 Urban Informality, Post-Disaster Management, and Challenges to Gender-Responsive Planning in Haiti Since the 2010 Earthquake Edad Mercier* Department of World History, St. John’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, St. John’s University, New York, United States Submission: August 28, 2020; Published: September 24, 2020 *Corresponding author: Edad Mercier, Department of World History, St. John’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, St. John’s University, New York City, United States Abstract the COVID-19 global pandemic early in 2020. The tiny nation (10,714 square miles) situated on the island of Hispaniola, still recovering from the devastatingHaitian officials, 2010 in earthquake, line with most which country claimed leaders the lives around of close the world,to two announcedhundred thousand a series people,of health, seemed hygiene prepared and safety to take precautions on the challenges following of COVID-19. Businesses and schools immediately closed, face masks and hand sanitizers were distributed by the thousands. But the effects of emergency injunctions that were not geared towards capacity-building, but rather prevention of rapid infectious disease transmission, could prove debilitating for the impoverished nation over the long-term. Primary and secondary school enrollment rates in Haiti are at an all-time low, and projections for the Haitian economy are dismal (-3.5% GDP growth 2020f) (World Bank 2020: 27). As a retrospective study, this paper conducts a critical quantitative and qualitative analysis of humanitarian aid, gender-based violence, and urbanism in Haiti, revealing that gender-responsive planning has a greater role to play in state-led disaster management plans and procedures for achieving long-term equity and sustainable economic growth. -

Sexed Pistols

United Nations University Press is the publishing arm of the United Nations University. UNU Press publishes scholarly and policy-oriented books and periodicals on the issues facing the United Nations and its peoples and member states, with particular emphasis upon international, regional and transboundary policies. The United Nations University was established as a subsidiary organ of the United Nations by General Assembly resolution 2951 (XXVII) of 11 December 1972. It functions as an international community of scholars engaged in research, postgraduate training and the dissemination of knowledge to address the pressing global problems of human survival, development and welfare that are the concern of the United Nations and its agencies. Its activities are devoted to advancing knowledge for human security and development and are focused on issues of peace and governance and environment and sustainable development. The Univer- sity operates through a worldwide network of research and training centres and programmes, and its planning and coordinating centre in Tokyo. Sexed pistols Sexed pistols: The gendered impacts of small arms and light weapons Edited by Vanessa Farr, Henri Myrttinen and Albrecht Schnabel United Nations a University Press TOKYO u NEW YORK u PARIS 6 United Nations University, 2009 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations University. United Nations University Press United Nations University, 53-70, Jingumae 5-chome, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 150-8925, Japan Tel: þ81-3-5467-1212 Fax: þ81-3-3406-7345 E-mail: [email protected] general enquiries: [email protected] http://www.unu.edu United Nations University Office at the United Nations, New York 2 United Nations Plaza, Room DC2-2060, New York, NY 10017, USA Tel: þ1-212-963-6387 Fax: þ1-212-371-9454 E-mail: [email protected] United Nations University Press is the publishing division of the United Nations University. -

Politique D'égalité Femmes Hommes 2014-2034

POLITIQUE D’ÉGALITÉ FEMMES HOMMES 2014-2034 ÉQUIPE DE RÉDACTION Dr Fritz SAINT FORT, expert en éducation Michelle ROMULUS, économiste, Coordonnatrice du programme financement pour l’égalité des sexes ONUFEMMES en Haïti Bonny JEAN BAPTISTE, doctorant, Spécialiste en économie et planification Raymond JEAN-BAPTISTE, Avocat, expert en communication et spécialiste en criminologie Marie Carmelle LAFONTANT, spécialiste en éducation et planification sociale, membre de cabinet du MCFDF France PAQUET, Coordonnatrice EFH du Projet d’Appui de Renforcement de la Gestion Publique (PARGEP) Marcelle GENDREAU, Responsable de l’Analyse différenciée selon le sexe (ADS) au gouvernement du Québec Denise AMÉDÉE, Directrice de la Direction de la prise en compte de l’Analyse selon le genre Nadine NAPOLÉON, économiste quantitative, assistante-directrice Gerty ADAM, Agronome, Coordonnatrice chargée des dossiers de gestion des risques et désastres à la direction générale du MCFDF Coordination et supervision Rose Esther SINCIMAT FLEURANT, Doctorante des Sciences Humaines et Sociales/ Experte en Genre et Développement, communicologue, Directrice Générale du MCFDF. Edition Kiskeya Publishing Co. www.mykpcbooks.com TOUS DROITS RÉSERVÉS Toute reproduction totale ou partielle de ce document est formellement interdite sans l’autorisation expresse du Ministère à la Condition Féminine et aux Droits des Femmes. Dépôt légal 14-04-129, Bibliothèque Nationale, Port-au-Prince, Haïti. Impression Les Presses Nationales d'Haïti- décembre 2014 TABLE DES MATIÈRES LISTE DES SIGLES ET ABRÉVIATIONS i MESSAGE DU PRÉSIDENT DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE iii MESSAGE DU PREMIER MINISTRE v MESSAGE DE LA MINISTRE À LA CONDITION FÉMININE vii REMERCIEMENTS ix INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPITRE I.- INÉGALITÉS DE GENRE 1.1 Accès à la justice et à la sécurité publique 6 1.1.1 Justice 6 1.1.2 Sécurité publique 8 1.2 Accès au travail et à l’emploi 10 1.2.1 Formation professionnelle 14 1.2.2. -

Usaid/Haiti Strategic Framework Gender Analysis

USAID/HAITI USAID/HAITI STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK GENDER ANALYSIS November 30, 2020 DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. This publication was produced for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Contract Number 47QRAA18D00CM. It was prepared by Banyan Global under the authorship of Jane Kellum, Sue Telingator, Kenise Phanord, and Alexandre Medginah Lynn. Implemented by: Banyan Global 1120 20th Street NW, Suite 950 Washington, DC 20036 Phone: +1 202-684-9367 Recommended Citation: Jane Kellum, Sue Telingator, Kenise Phanord, and Alexandre Medginah Lynn. USAID/Haiti Strategic Framework Gender Analysis Report. Prepared by Banyan Global. 2020 1 | USAID/HAITI STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK GENDER ANALYSIS USAID.GOV ACRONYMS ADS Automated Directives System AFASDA Association Femmes Soleil d'Haiti /Sun of Haiti women's association AOR/COR Agreement Officer’s Representative/Contract Officer’s Representative APN L'Autorité Portuaire Nationale/National Port Authority ARI Acute respiratory infections ASEC Assemblée de la Section Communale/Assembly of the Communal Section BDS Business development services BINUH Bureau intégré des Nations Unies en Haïti/United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti CAEPA Comité d’Approvisionnement en Eau Potable et Assainissement/Potable Water and Sanitation Provision Committee CASEC Conseil d'Administration de la Section Communale/Board of Directors of the Communal Section -

Haiti After the Elections: Challenges for Préval’S First 100 Days

Policy Briefing Latin America/Caribbean Briefing N°10 Port-au-Prince/Brussels, 11 May 2006 Haiti after the Elections: Challenges for Préval’s First 100 Days I. OVERVIEW Deep structural challenges still threaten what may be Haiti’s last chance to extricate itself from chaos and despair, and action in the first 100 days is needed to René Préval’s inauguration on 14 May 2006 opens a convey to Haitians that a new chapter has been opened crucial window of opportunity for Haiti to move beyond in their history. political polarisation, crime and economic decline. The Security. It is essential to preserve the much 7 February presidential and parliamentary elections improved security situation in the capital since the succeeded despite logistical problems, missing tally sheets end of January. In large part the improvement stems and the after-the-fact reinterpretation of the electoral from a tacit truce declared by some of the main law. There was little violence, turnout was high, and the gangs – especially those in Cité Soleil – whose results reflected the general will. The 21 April second leaders support Préval. The new administration round parliamentary elections were at least as calm, and and MINUSTAH should pursue efforts to combine although turnout was lower, the electoral machinery reduced gang violence with rapid implementation of operated more effectively. During his first 100 days high-profile interventions to benefit the inhabitants in office, the new president needs to form a governing of the capital’s worst urban districts. Urgent action partnership with a multi-party parliament, show Haitians is needed to disarm and dismantle urban and rural some visible progress with international help and build armed gangs through a re-focused Disarmament, on a rare climate of optimism in the country. -

PORT-AU-PRINCE and MONTREAL, 1934-1986 by Grace Louise Sanders a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requiremen

LA VOIX DES FEMMES: HAITIAN WOMEN’S RIGHTS, NATIONAL POLITICS AND BLACK ACTIVISM IN PORT-AU-PRINCE AND MONTREAL, 1934-1986 by Grace Louise Sanders A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History and Women’s Studies) in the University of Michigan 2013 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Sueann Caulfield, Chair Associate Professor Jesse E. Hoffnung-Garskof Professor Tiya A. Miles Associate Professor Nadine C. Naber Professor Matthew J. Smith, University of the West Indies © Grace L. Sanders 2013 DEDICATION For LaRosa, Margaret, and Johnnie, the two librarians and the eternal student, who insisted that I honor the freedom to read and write. & For the women of Le Cercle. Nou se famn tout bon! ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the History and Women’s Studies Departments at the University of Michigan. I am especially grateful to my Dissertation Committee Members. Matthew J. Smith, thank you for your close reading of everything I send to you, from emails to dissertation chapters. You have continued to be selfless in your attention to detail and in your mentorship. Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, thank you for sharing new and compelling ways to narrate and teach the histories of Latin America and North America. Tiya Miles, thank you for being a compassionate mentor and inspiring visionary. I have learned volumes from your example. Nadine Naber, thank you for kindly taking me by the hand during the most difficult times on this journey. You are an ally and a friend. Sueann Caulfield, you have patiently walked this graduate school road with me from beginning to end. -

Articulating Feminisms in the Translation of Marie Vieux- Chauvet's Les Rapaces Carolyn P T Shread University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2008 On Becoming in Translation: Articulating Feminisms in the Translation of Marie Vieux- Chauvet's Les Rapaces Carolyn P T Shread University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Shread, Carolyn P T, "On Becoming in Translation: Articulating Feminisms in the Translation of Marie Vieux-Chauvet's Les Rapaces" (2008). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 199. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/199 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON BECOMING IN TRANSLATION: ARTICULATING FEMINISMS IN THE TRANSLATION OF MARIE VIEUX-CHAUVET’S LES RAPACES A Thesis Presented by CAROLYN P. T. SHREAD Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 2008 Comparative Literature Translation Studies © Copyright by Carolyn P. T. Shread 2008 All Rights Reserved ON BECOMING IN TRANSLATION: ARTICULATING FEMINISMS IN THE TRANSLATION OF MARIE VIEUX-CHAUVET’S LES RAPACES A Thesis Presented by CAROLYN P. T. SHREAD Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________________ Edwin -

UNDP GEF Annotated Project Document Template

United Nations Development Programme Project Document template for projects financed by the various GEF Trust Funds Project title: Sustainable management of wooded production landscapes for biodiversity conservation Country(ies): Haiti Implementing Partner (GEF Executing Execution Modality: Agency- Entity): FAO implemented Contributing Outcome (UNDAF/CPD, RPD, GPD): National, regional and local institutions and civil society improve the management of rural and urban areas, agriculture and the environment, and mechanisms for preventing and reducing risks in order to improve the resilience of the population to natural disasters and to climate change. UNDP Social and Environmental Screening Category: UNDP Gender Marker: 2 Moderate Atlas Award ID: 00128886 Atlas Project/Output ID: 00122730 UNDP-GEF PIMS ID number: 5765 GEF Project ID number: 9777 LPAC meeting date: Latest possible date to submit to GEF: Latest possible CEO endorsement date: Planned start date: June, 2021 Planned end date: May, 2028 Expected date of Mid-Term Review: March, 2025 Expected date of Terminal evaluation: September, 2027 Brief project description: This project will generate major biodiversity benefits, as well as sustainable land management benefits and collateral gender-sensitive socioeconomic/livelihood benefits by enhancing conditions and capacities among farmers in the north of Haiti to manage BD-friendly, sustainable and economically viable tree-based production systems (diversified cacao, coffee and home gardens). (1) FINANCING PLAN (only cash transferred to -

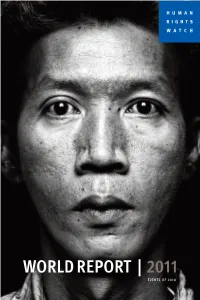

WORLDREPORT Rights to Ensure That the Quest for Cooperation Does Not Become an Excuse for Inaction

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH WORLD REPOR T | 2011 EVENTS OF 2010 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH WORLD REPORT 2011 EVENTS OF 2010 Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN-13: 978-1-58322-921-7 Front cover photo: Aung Myo Thein, 42, spent more than six years in prison in Burma for his activism as a student union leader. More than 2,200 political prisoners—including artists, journalists, students, monks, and political activists—remain locked up in Burma's squalid prisons. © 2010 Platon for Human Rights Watch Back cover photo: A child migrant worker from Kyrgyzstan picks tobacco leaves in Kazakhstan. Every year thousands of Kyrgyz migrant workers, often together with their chil- dren, find work in tobacco farming, where many are subjected to abuse and exploitation by employers. © 2009 Moises Saman/Magnum for Human Rights Watch Cover and book design by Rafael Jiménez 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor 51 Avenue Blanc, Floor 6, New York, NY 10118-3299 USA 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +1 212 290 4700 Tel: +41 22 738 0481 Fax: +1 212 736 1300 Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Poststraße 4-5 Washington, DC 20009 USA 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +1 202 612 4321 Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10 Fax: +1 202 612 4333 Fax: +49 30 2593 06-29 [email protected] [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor 1st fl, Wilds View London N1 9HF, UK Isle of Houghton Tel: +44 20 7713 1995 Boundary Road (at Carse O’Gowrie) Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 Parktown, 2198 South Africa [email protected] Tel: +27-11-484-2640, Fax: +27-11-484-2641 27 Rue de Lisbonne #4A, Meiji University Academy Common bldg.