Usaid/Haiti Strategic Framework Gender Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

United Nations CEDAW/C/HTI/7 Convention on the Elimination Distr.: General of All Forms of Discrimination 9 July 2008 English against Women Original: French Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women Combined initial, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh periodic reports of States parties Haiti* * The present report is being issued without formal editing. 08-41624 (E) 090708 050908 *0841624* CEDAW/C/HTI/7 LIBERTY EQUALITY FRATERNITY REPUBLIC OF HAITI Implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women CEDAW COMBINED REPORTS 1982, 1986, l990, 1994, 1998, 2002 and 2006 Port-au-Prince March 2008 2 08-41624 CEDAW/C/HTI/7 FOREWORD On behalf of the Republic of Haiti, I am proud to present in the pages that follow the reports on implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. The Convention was ratified in 1981 and, pursuant to article 18 of that same Convention, the Government of Haiti should have submitted an initial implementation report one year after ratification and another every four years thereafter. To compensate for failure to produce those reports, starting in April 2006 the Ministry for the Status of Women and Women’s Rights stepped up its activities and embarked on the process of preparing the report. That report is of the utmost importance to the Haitian State. It enables it to evaluate and systematize progress made with respect to women’s rights and to establish priorities for the future. -

Mathilde Pierre Weak Judicial Systems And

Mathilde Pierre Weak Judicial Systems and Systematic Sexual Violence against Women and Girls: The Socially Constructed Vulnerability of Female Bodies in Haiti This thesis has been submitted on this day of April 16, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the degree requirements for the NYU Global Liberal Studies Bachelor of Arts degree. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor Emily Bauman, who has guided me through every step in the year-long process of writing my thesis. The time and energy she invested in thoroughly reading and commenting on my work, in recommending other avenues of further research, and in pushing me to deepen my analysis were truly invaluable. I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Joyce Apsel who, although abroad in Florence, Italy, set aside time to speak with me over Skype, to comment on my rough draft, and to advise me on the approach of my argument in my thesis. I would additionally like to thank all of the individuals who set aside considerable time to meet with me for interviews in Port-au-Prince, most notably Attorney Claudy Gassant, Attorney Rosy Auguste, Attorney Marie Alice Belisaire, Attorney Giovanna Menard, Judge Jean Wilner Morin, Carol Pierre-Paul Jacob, Marie Yolaine Gilles, and Officer Guerson Joseph. Finally I extend a heartfelt thank you to my parents, Mathias and Gaëlle Pierre, who greatly assisted in connecting me with the individuals I interviewed and whose constant support and encouragement helped me to push through in the completion of my thesis. 1 ABSTRACT Widespread sexual violence against women and girls in Haiti is a phenomenon that largely persists due to a failure to prosecute male perpetrators and enforce the domestic and international laws that exist to criminalize rape. -

BEYOND-SHOCK-Nov-2012-Report-On-GBV-Progress

BEYOND SHOCK Charting the landscape of sexual violence in post-quake Haiti: Progress, Challenges & Emerging Trends 2010-2012 Anne-christine d’Adesky with PotoFanm+Fi Foreword by Edwidge Danticat | Photo essay by Nadia Todres November 2012 www.potofi.org | www.potofanm.org Report Sponsors: Trocaire, World Pulse & Tides Beyond Shock report 11.26 ABRIDGED VERSION (SHORT REPORT) Author: Anne‐christine d’Adesky and the PotoFanm+Fi coalition © PotoFanm+Fi November 2012. All Rights Reserved. www.potofanm.org For information, media inquiries, report copies: Contact: Anne‐christine d’Adesky Report Coordinator, PotoFanm+Fi Email: [email protected] Haiti: +508 | 3438 2315 US: (415) 690‐6199 1 Beyond Shock DEDICATION This report is dedicated to Haitians who are victims of crimes of sexual violence, including those affected after the historic 2010 earthquake. Some died of injuries related to these crimes. Others have committed suicide, unable to bear injustice and further suffering. May they rest in peace. May we continue to seek justice in their names. Let their memory serve as a reminder of the sacredness of every human life and the moral necessity to act with all our means to protect it. It is also dedicated to the survivors who have had the courage to step out of the shadows of shock, pain, suffering, indignity, and silence and into recovery and public advocacy. Their voices guide a growing grassroots movement. We also acknowledge and thank the many individuals and groups in and outside Haiti – community activists, political leaders, health providers, police officers, lawyers, judges, witnesses, caretakers and family members, human rights and gender activists, journalists and educators – who carry the torch. -

Urban Informality, Post-Disaster Management, and Challenges to Gender-Responsive Planning in Haiti Since the 2010 Earthquake

Research Article Ann Soc Sci Manage Stud Volume 5 Issue 5 - September 2020 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Edad Mercier DOI: 10.19080/ASM.2020.05.555675 Urban Informality, Post-Disaster Management, and Challenges to Gender-Responsive Planning in Haiti Since the 2010 Earthquake Edad Mercier* Department of World History, St. John’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, St. John’s University, New York, United States Submission: August 28, 2020; Published: September 24, 2020 *Corresponding author: Edad Mercier, Department of World History, St. John’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, St. John’s University, New York City, United States Abstract the COVID-19 global pandemic early in 2020. The tiny nation (10,714 square miles) situated on the island of Hispaniola, still recovering from the devastatingHaitian officials, 2010 in earthquake, line with most which country claimed leaders the lives around of close the world,to two announcedhundred thousand a series people,of health, seemed hygiene prepared and safety to take precautions on the challenges following of COVID-19. Businesses and schools immediately closed, face masks and hand sanitizers were distributed by the thousands. But the effects of emergency injunctions that were not geared towards capacity-building, but rather prevention of rapid infectious disease transmission, could prove debilitating for the impoverished nation over the long-term. Primary and secondary school enrollment rates in Haiti are at an all-time low, and projections for the Haitian economy are dismal (-3.5% GDP growth 2020f) (World Bank 2020: 27). As a retrospective study, this paper conducts a critical quantitative and qualitative analysis of humanitarian aid, gender-based violence, and urbanism in Haiti, revealing that gender-responsive planning has a greater role to play in state-led disaster management plans and procedures for achieving long-term equity and sustainable economic growth. -

FOSTERING Resiliencefor Childrenin ADVERSITY

FOSTERING RESILIENCE for CHILDREN in ADVERSITY: A Guide to Whole Child School-Community Approaches FOSTERING RESILIENCE FOR CHILDREN IN ADVERSITY A Table of Contents Introduction 1 Audience 2 SECTION 1 Resilience and Adversity 3 What Creates Risk? What Promotes Resilience? 4 Building Blocks of Children’s Resilience 6 Basic Needs Highlight 7 Housing 7 Nutritious Food 7 Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) 8 Health care 8 Physical safety and security 9 Nurturing Relationships Highlight 9 Parents and Caregivers 9 Teachers 10 Peers 10 Core Capabilities and Values: Social and Emotional Learning 10 Contextualization is Key 13 Resilience Building Principles 16 TABLE OF CONTENTS (CONT’D) SECTION 2 Whole Child School-Community Approaches 17 Essential Players in the School-Community Approach to Fostering Resilience: the home, the school, and the community 20 The Home 20 Early Childhood Development 20 Adolescent Development 23 Supporting Parents 24 The School 26 Academic Resilience 26 Safe spaces 28 Curriculum 30 SEL 31 Teacher Training and Well-being 34 Community 36 SECTION 3 Research and Learning 39 Understand risk and protection across building blocks and settings 40 Focus on equity as a key dimension of the matrixed needs assessment 42 Measure learning and development outcomes rather than resilience 43 Systems Resilience Post-COVID-19 44 Putting the Pieces Together 47 Introduction Education and resilience have a strong reciprocal relationship: participation in education promotes children’s resilience, and resilient children are more likely to participate in, and to benefit from, education. For example, strong cognitive competencies are key components of resilience that are strengthened by quality education. -

ITN-IEA PAP Information Ecosystem

Port-au-Prince Information Ecosystem Assessment May-August 2020 I. Executive Summary 1 II. Summary of Key Findings 3 III. Background 23 IV. Research Methodology 26 Thwarting V. Media Landscape 34 Haiti Media Landscape 34 Disinformation and Port-au-Prince Media Landscape 37 VI. Key Findings - Information Ecosystem Assessment 43 Promoting Quality 1. Information Sources 43 2. Information Needs 48 Information in Haiti 3. Access to Information 56 4. Disinformation 66 VII. Suggestions and Next Steps 70 VIII. Acknowledgments 81 Executive Summary The Information Ecosystem Assessment (IEA) is a study designed to understand the visits and building relationships in the community – to follow the World Health Organi- dynamics of transmission, production, and consumption of information in a given envi- zation’s recommendations of social distancing, as well as restrictions imposed by the ronment. Understanding the flow of information, its sources, channels, and the factors state of emergency decreed by the government of Haiti. Data was collected using a mix that affect it – intentionally or unintentionally– can help to empower citizens to make of methodologies including thorough online and telephone surveys and interviews, and better-informed decisions, bridge divides, participate more fully in their communities, small, in-person focus groups that followed strict safety measures and were conducted and hold power to account. This study attempts to answer questions of access to infor- after restrictions were lifted. The IEA is not an exhaustive study; therefore, the results mation, the tools used, how information is shared, what information is trusted and used, should not be treated as such. Nevertheless, Internews and Panos Caribbean ensured and what type of information is needed by the selected communities and sub-groups. -

Sexed Pistols

United Nations University Press is the publishing arm of the United Nations University. UNU Press publishes scholarly and policy-oriented books and periodicals on the issues facing the United Nations and its peoples and member states, with particular emphasis upon international, regional and transboundary policies. The United Nations University was established as a subsidiary organ of the United Nations by General Assembly resolution 2951 (XXVII) of 11 December 1972. It functions as an international community of scholars engaged in research, postgraduate training and the dissemination of knowledge to address the pressing global problems of human survival, development and welfare that are the concern of the United Nations and its agencies. Its activities are devoted to advancing knowledge for human security and development and are focused on issues of peace and governance and environment and sustainable development. The Univer- sity operates through a worldwide network of research and training centres and programmes, and its planning and coordinating centre in Tokyo. Sexed pistols Sexed pistols: The gendered impacts of small arms and light weapons Edited by Vanessa Farr, Henri Myrttinen and Albrecht Schnabel United Nations a University Press TOKYO u NEW YORK u PARIS 6 United Nations University, 2009 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations University. United Nations University Press United Nations University, 53-70, Jingumae 5-chome, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 150-8925, Japan Tel: þ81-3-5467-1212 Fax: þ81-3-3406-7345 E-mail: [email protected] general enquiries: [email protected] http://www.unu.edu United Nations University Office at the United Nations, New York 2 United Nations Plaza, Room DC2-2060, New York, NY 10017, USA Tel: þ1-212-963-6387 Fax: þ1-212-371-9454 E-mail: [email protected] United Nations University Press is the publishing division of the United Nations University. -

Politique D'égalité Femmes Hommes 2014-2034

POLITIQUE D’ÉGALITÉ FEMMES HOMMES 2014-2034 ÉQUIPE DE RÉDACTION Dr Fritz SAINT FORT, expert en éducation Michelle ROMULUS, économiste, Coordonnatrice du programme financement pour l’égalité des sexes ONUFEMMES en Haïti Bonny JEAN BAPTISTE, doctorant, Spécialiste en économie et planification Raymond JEAN-BAPTISTE, Avocat, expert en communication et spécialiste en criminologie Marie Carmelle LAFONTANT, spécialiste en éducation et planification sociale, membre de cabinet du MCFDF France PAQUET, Coordonnatrice EFH du Projet d’Appui de Renforcement de la Gestion Publique (PARGEP) Marcelle GENDREAU, Responsable de l’Analyse différenciée selon le sexe (ADS) au gouvernement du Québec Denise AMÉDÉE, Directrice de la Direction de la prise en compte de l’Analyse selon le genre Nadine NAPOLÉON, économiste quantitative, assistante-directrice Gerty ADAM, Agronome, Coordonnatrice chargée des dossiers de gestion des risques et désastres à la direction générale du MCFDF Coordination et supervision Rose Esther SINCIMAT FLEURANT, Doctorante des Sciences Humaines et Sociales/ Experte en Genre et Développement, communicologue, Directrice Générale du MCFDF. Edition Kiskeya Publishing Co. www.mykpcbooks.com TOUS DROITS RÉSERVÉS Toute reproduction totale ou partielle de ce document est formellement interdite sans l’autorisation expresse du Ministère à la Condition Féminine et aux Droits des Femmes. Dépôt légal 14-04-129, Bibliothèque Nationale, Port-au-Prince, Haïti. Impression Les Presses Nationales d'Haïti- décembre 2014 TABLE DES MATIÈRES LISTE DES SIGLES ET ABRÉVIATIONS i MESSAGE DU PRÉSIDENT DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE iii MESSAGE DU PREMIER MINISTRE v MESSAGE DE LA MINISTRE À LA CONDITION FÉMININE vii REMERCIEMENTS ix INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPITRE I.- INÉGALITÉS DE GENRE 1.1 Accès à la justice et à la sécurité publique 6 1.1.1 Justice 6 1.1.2 Sécurité publique 8 1.2 Accès au travail et à l’emploi 10 1.2.1 Formation professionnelle 14 1.2.2. -

Haiti After the Elections: Challenges for Préval’S First 100 Days

Policy Briefing Latin America/Caribbean Briefing N°10 Port-au-Prince/Brussels, 11 May 2006 Haiti after the Elections: Challenges for Préval’s First 100 Days I. OVERVIEW Deep structural challenges still threaten what may be Haiti’s last chance to extricate itself from chaos and despair, and action in the first 100 days is needed to René Préval’s inauguration on 14 May 2006 opens a convey to Haitians that a new chapter has been opened crucial window of opportunity for Haiti to move beyond in their history. political polarisation, crime and economic decline. The Security. It is essential to preserve the much 7 February presidential and parliamentary elections improved security situation in the capital since the succeeded despite logistical problems, missing tally sheets end of January. In large part the improvement stems and the after-the-fact reinterpretation of the electoral from a tacit truce declared by some of the main law. There was little violence, turnout was high, and the gangs – especially those in Cité Soleil – whose results reflected the general will. The 21 April second leaders support Préval. The new administration round parliamentary elections were at least as calm, and and MINUSTAH should pursue efforts to combine although turnout was lower, the electoral machinery reduced gang violence with rapid implementation of operated more effectively. During his first 100 days high-profile interventions to benefit the inhabitants in office, the new president needs to form a governing of the capital’s worst urban districts. Urgent action partnership with a multi-party parliament, show Haitians is needed to disarm and dismantle urban and rural some visible progress with international help and build armed gangs through a re-focused Disarmament, on a rare climate of optimism in the country. -

PORT-AU-PRINCE and MONTREAL, 1934-1986 by Grace Louise Sanders a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requiremen

LA VOIX DES FEMMES: HAITIAN WOMEN’S RIGHTS, NATIONAL POLITICS AND BLACK ACTIVISM IN PORT-AU-PRINCE AND MONTREAL, 1934-1986 by Grace Louise Sanders A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History and Women’s Studies) in the University of Michigan 2013 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Sueann Caulfield, Chair Associate Professor Jesse E. Hoffnung-Garskof Professor Tiya A. Miles Associate Professor Nadine C. Naber Professor Matthew J. Smith, University of the West Indies © Grace L. Sanders 2013 DEDICATION For LaRosa, Margaret, and Johnnie, the two librarians and the eternal student, who insisted that I honor the freedom to read and write. & For the women of Le Cercle. Nou se famn tout bon! ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the History and Women’s Studies Departments at the University of Michigan. I am especially grateful to my Dissertation Committee Members. Matthew J. Smith, thank you for your close reading of everything I send to you, from emails to dissertation chapters. You have continued to be selfless in your attention to detail and in your mentorship. Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, thank you for sharing new and compelling ways to narrate and teach the histories of Latin America and North America. Tiya Miles, thank you for being a compassionate mentor and inspiring visionary. I have learned volumes from your example. Nadine Naber, thank you for kindly taking me by the hand during the most difficult times on this journey. You are an ally and a friend. Sueann Caulfield, you have patiently walked this graduate school road with me from beginning to end. -

U.S. Export Sales

This summary is based on reports from exporters for the period July 30-August 5, 2021. Wheat: Net sales of 293,100 metric tons (MT) for 2021/2022 were down 5 percent from the previous week and 32 percent from the prior 4-week average. Increases primarily for unknown destinations (98,600 MT, including 82,600 MT - late), Japan (34,300 MT, including decreases of 700 MT and 500 MT - late), Nigeria (31,800 MT), Venezuela (27,100 MT – late), and Chile (21,500 MT), were offset by reductions primarily for the Dominican Republic (17,400 MT) and Guatemala (5,000 MT). Exports of 627,900 MT--a marketing-year high--were up 62 percent from the previous week and 60 percent from the prior 4-week average. The destinations were primarily to Japan (130,400 MT, including 500 MT - late), Mexico (89,600 MT), Nigeria (82,300 MT), China (64,700 MT), and South Korea (62,800 MT). Late Reporting: For 2020/2021, net sales totaling 123,800 MT of wheat were reported late for unknown destinations (82,600 MT), Venezuela (27,100 MT), Haiti (11,500 MT), Leeward and Windward Islands (2,200 MT), and Japan (500 MT). Exports totaling 41,300 MT of wheat were reported late to Venezuela (27,100 MT), Haiti (11,500 MT), Leeward and Windward Islands (2,200 MT), and Japan (500 MT). Corn: Net sales of 377,600 MT for 2020/2021 were up noticeably from the previous week and from the prior 4-week average. Increases primarily for Mexico (144,500 MT, including decreases of 38,500 MT), Japan (80,500 MT, including 81,700 MT switched from unknown destinations and decreases of 1,200 MT), Venezuela (59,200 MT, including 39,200 MT - late), Colombia (54,800 MT, including 21,000 MT switched from unknown destinations and 31,700 MT - late), and Canada (45,700 MT, including decreases of 8,900 MT), were offset by reductions primarily for unknown destinations (76,800 MT) and the Dominican Republic (7,500 MT). -

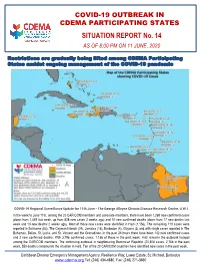

SITUATION REPORT No. 14 AS of 8:00 PM on 11 JUNE, 2020

COVID-19 OUTBREAK IN CDEMA PARTICIPATING STATES SITUATION REPORT No. 14 AS OF 8:00 PM ON 11 JUNE, 2020 Restrictions are gradually being lifted among CDEMA Participating States amidst ongoing management of the COVID-19 pandemic COVID-19 Regional Surveillance Update for 11th June - The George Alleyne Chronic Disease Research Centre, U.W.I. In the week to June 11th, among the 20 CARICOM members and associate members, there have been 1,269 new confirmed cases (down from 1,449 last week, up from 828 new cases 2 weeks ago) and 10 new confirmed deaths (down from 17 new deaths last week and 13 new deaths 2 weeks ago). Most of these new cases were identified in Haiti (1,156). The remaining 113 cases were reported in Suriname (63), The Cayman Islands (24), Jamaica (15), Barbados (4), Guyana (3) and with single cases reported in The Bahamas, Belize, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. In the past 24 hours there have been 142 new confirmed cases and 2 new confirmed deaths. With 3,796 confirmed cases, 1,156 of these in the past week, Haiti remains the outbreak hotspot among the CARICOM members. The continuing outbreak in neighbouring Dominican Republic (20,808 cases, 2,768 in the past week, 550 deaths) compounds the situation in Haiti. Ten of the 20 CARICOM countries have identified new cases in the past week. Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency. Resilience Way, Lower Estate, St. Michael, Barbados www.cdema.org Tel: (246) 434-4880, Fax: (246) 271-3660 CDEMA’s Situation Report #14 2 Updates from CDEMA Participating States ANGUILLA – Department of Disaster Management (DDM) Cases ● There are currently no active COVID 19 cases, with no reported deaths.