Sexed Pistols

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

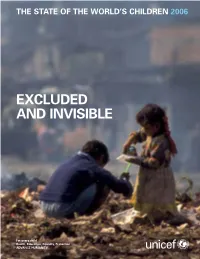

Excluded and Invisible

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2006 EXCLUDED AND INVISIBLE THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2006 © The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2005 The Library of Congress has catalogued this serial publication as follows: Permission to reproduce any part of this publication The State of the World’s Children 2006 is required. Please contact the Editorial and Publications Section, Division of Communication, UNICEF, UNICEF House, 3 UN Plaza, UNICEF NY (3 UN Plaza, NY, NY 10017) USA, New York, NY 10017, USA Tel: 212-326-7434 or 7286, Fax: 212-303-7985, E-mail: [email protected]. Permission E-mail: [email protected] will be freely granted to educational or non-profit Website: www.unicef.org organizations. Others will be requested to pay a small fee. Cover photo: © UNICEF/HQ94-1393/Shehzad Noorani ISBN-13: 978-92-806-3916-2 ISBN-10: 92-806-3916-1 Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the advice and contributions of many inside and outside of UNICEF who provided helpful comments and made other contributions. Significant contributions were received from the following UNICEF field offices: Albania, Armenia, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, China, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Guinea-Bissau, Jordan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mexico, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Occupied Palestinian Territory, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Republic of Moldova, Serbia and Montenegro, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Venezuela and Viet Nam. Input was also received from Programme Division, Division of Policy and Planning and Division of Communication at Headquarters, UNICEF regional offices, the Innocenti Research Centre, the UK National Committee and the US Fund for UNICEF. -

Sierra Leone

SIERRA LEONE 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 1 (A) – January 2003 I was captured together with my husband, my three young children and other civilians as we were fleeing from the RUF when they entered Jaiweii. Two rebels asked to have sex with me but when I refused, they beat me with the butt of their guns. My legs were bruised and I lost my three front teeth. Then the two rebels raped me in front of my children and other civilians. Many other women were raped in public places. I also heard of a woman from Kalu village near Jaiweii being raped only one week after having given birth. The RUF stayed in Jaiweii village for four months and I was raped by three other wicked rebels throughout this A woman receives psychological and medical treatment in a clinic to assist rape period. victims in Freetown. In January 1999, she was gang-raped by seven revels in her village in northern Sierra Leone. After raping her, the rebels tied her down and placed burning charcoal on her body. (c) 1999 Corinne Dufka/Human Rights -Testimony to Human Rights Watch Watch “WE’LL KILL YOU IF YOU CRY” SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE SIERRA LEONE CONFLICT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] January 2003 Vol. -

The Legacy of 2002 in Koroba-Lake Kopiago Open Electorate

21. Results at any Cost? The Legacy of 2002 in Koroba-Lake Kopiago Open Electorate Nicole Haley In June 2007, the people of Koroba-Lake Kopiago went to the polls for the fourth time in five years. The election was of particular interest because Koroba-Lake Kopiago was one of the six open electorates in which the 2002 general election had been deemed to have failed, and was one of the 10 electorates around the country that had had a limited preferential voting (LPV) by-election prior to the general election. It is also an electorate that has been subject to election studies in the past (see Haley 2002, 2004, 2006 and Robinson 2002) and for which there is consequently a great deal of comparative longitudinal data. This chapter draws upon observations and findings of both the 2006 Koroba-Lake Kopiago by-election observation team (Haley 2006) and the 2007 Koroba-Lake Kopiago domestic observation team.1 It finds that the election was anything but fair, yet despite fraud and malpractice on a scale never before seen the election was widely held to have been successful and a significant improvement on 2002. It further suggests that the national government and Papua New Guinea Electoral Commission (PNGEC) were willing to accept results at any cost in order to avoid a repetition of the events of 2002 (Somare 2006:5), and advocates a more honest assessment of future elections. The integrity of elections cannot merely be asserted but must be demonstrated. Background Koroba-Lake Kopiago is one of eight open electorates in Southern Highlands Province (Figure 20.1). -

2018 COMMITTEE AMENDMENT Bill No. SPB 7026 Ì831648BÎ831648 Page 1 of 24 2/26/2018 2:07:33 PM 595-03718-18

Florida Senate - 2018 COMMITTEE AMENDMENT Bill No. SPB 7026 831648 Ì831648BÎ LEGISLATIVE ACTION Senate . House . The Committee on Rules (Rodriguez) recommended the following: 1 Senate Amendment to Amendment (345360) (with title 2 amendment) 3 4 Between lines 209 and 210 5 insert: 6 Section 8. Section 790.30, Florida Statutes, is created to 7 read: 8 790.30 Assault weapons.— 9 (1) DEFINITIONS.—As used in this section, the term: 10 (a) “Assault weapon” means: 11 1. A selective-fire firearm capable of fully automatic, Page 1 of 24 2/26/2018 2:07:33 PM 595-03718-18 Florida Senate - 2018 COMMITTEE AMENDMENT Bill No. SPB 7026 831648 Ì831648BÎ 12 semiautomatic, or burst fire at the option of the user or any of 13 the following specified semiautomatic firearms: 14 a. Algimec AGM1. 15 b. All AK series, including, but not limited to, the 16 following: AK, AK-47, AK-74, AKM, AKS, ARM, MAK90, MISR, NHM90, 17 NHM91, Rock River Arms LAR-47, SA 85, SA 93, Vector Arms AK-47, 18 VEPR, WASR-10, and WUM. 19 c. All AR series, including, but not limited to, the 20 following: AR-10, AR-15, Armalite AR-180, Armalite M-15, AR-70, 21 Bushmaster XM15, Colt AR-15, DoubleStar AR rifles, DPMS tactical 22 rifles, Olympic Arms, Rock River Arms LAR-15, and Smith & Wesson 23 M&P15 rifles. 24 d. Barrett 82A1 and REC7. 25 e. Beretta AR-70 and Beretta Storm. 26 f. Bushmaster automatic rifle. 27 g. Calico Liberty series rifles. 28 h. Chartered Industries of Singapore SR-88. -

Extremism and Terrorism

Ireland: Extremism and Terrorism On December 19, 2019, Cloverhill District Court in Dublin granted Lisa Smith bail following an appeal hearing. Smith, a former member of the Irish Defense Forces, was arrested at Dublin Airport on suspicion of terrorism offenses following her return from Turkey in November 2019. According to Irish authorities, Smith was allegedly a member of ISIS. Smith was later examined by Professor Anne Speckhard who determined that Smith had “no interest in rejoining or returning to the Islamic State.” Smith’s trial is scheduled for January 2022. (Sources: Belfast Telegraph, Irish Post) Ireland saw an increase in Islamist and far-right extremism throughout 2019, according to Europol. In 2019, Irish authorities arrested five people on suspicions of supporting “jihadi terrorism.” This included Smith’s November 2019 arrest. An additional four people were arrested for financing jihadist terrorism. Europol also noted a rise in far-right extremism, based on the number of Irish users in leaked user data from the far-right website Iron March. (Source: Irish Times) Beginning in late 2019, concerns grew that the possible return of a hard border between British-ruled Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland after Brexit could increase security tensions in the once war-torn province. The Police Services of Northern Ireland recorded an increase in violent attacks along the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland border in 2019 and called on politicians to take action to heal enduring divisions in society. According to a representative for the New IRA—Northern Ireland’s largest dissident organization—the uncertainty surrounding Brexit provided the group a politicized platform to carry out attacks along the U.K. -

Millions of Civilians Have Been Killed in the Flames of War... But

VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 131 • 2003 “Millions of civilians have been killed in the flames of war... But there is hope too… in places like Sierra Leone, Angola and in the Horn of Africa.” —High Commissioner RUUD LUBBERS at a CrossroadsAfrica N°131 - 2003 Editor: Ray Wilkinson French editor: Mounira Skandrani Contributors: Millicent Mutuli, Astrid Van Genderen Stort, Delphine Marie, Peter Kessler, Panos Moumtzis Editorial assistant: UNHCR/M. CAVINATO/DP/BDI•2003 2 EDITORIAL Virginia Zekrya Africa is at another Africa slips deeper into misery as the world Photo department: crossroads. There is Suzy Hopper, plenty of good news as focuses on Iraq. Anne Kellner 12 hundreds of thousands of Design: persons returned to Sierra Vincent Winter Associés Leone, Angola, Burundi 4 AFRICAN IMAGES Production: (pictured) and the Horn of Françoise Jaccoud Africa. But wars continued in A pictorial on the African continent. Photo engraving: Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia and Aloha Scan - Geneva other areas, making it a very Distribution: mixed picture for the 12 COVER STORY John O’Connor, Frédéric Tissot continent. In an era of short wars and limited casualties, Maps: events in Africa are almost incomprehensible. UNHCR Mapping Unit By Ray Wilkinson Historical documents UNHCR archives Africa at a glance A brief look at the continent. Refugees is published by the Media Relations and Public Information Service of the United Nations High Map Commissioner for Refugees. The 17 opinions expressed by contributors Refugee and internally displaced are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do UNHCR/P. KESSLER/DP/IRQ•2003 populations. not imply the expression of any With the war in Iraq Military opinion or recognition on the part of officially over, UNHCR concerning the legal status UNHCR has turned its Refugee camps are centers for of a territory or of its authorities. -

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

United Nations CEDAW/C/HTI/7 Convention on the Elimination Distr.: General of All Forms of Discrimination 9 July 2008 English against Women Original: French Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women Combined initial, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh periodic reports of States parties Haiti* * The present report is being issued without formal editing. 08-41624 (E) 090708 050908 *0841624* CEDAW/C/HTI/7 LIBERTY EQUALITY FRATERNITY REPUBLIC OF HAITI Implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women CEDAW COMBINED REPORTS 1982, 1986, l990, 1994, 1998, 2002 and 2006 Port-au-Prince March 2008 2 08-41624 CEDAW/C/HTI/7 FOREWORD On behalf of the Republic of Haiti, I am proud to present in the pages that follow the reports on implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. The Convention was ratified in 1981 and, pursuant to article 18 of that same Convention, the Government of Haiti should have submitted an initial implementation report one year after ratification and another every four years thereafter. To compensate for failure to produce those reports, starting in April 2006 the Ministry for the Status of Women and Women’s Rights stepped up its activities and embarked on the process of preparing the report. That report is of the utmost importance to the Haitian State. It enables it to evaluate and systematize progress made with respect to women’s rights and to establish priorities for the future. -

The Impacts of Small Arms Availability and Misuse in Sri Lanka

In the Shadow of a Cease-fire: The Impacts of Small Arms Availability and Misuse in Sri Lanka by Chris Smith October 2003 A publication of the Small Arms Survey Chris Smith The Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey is an independent research project located at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. It is also linked to the Graduate Institute’s Programme for Strategic and International Security Studies. Established in 1999, the project is supported by the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, and by contributions from the Governments of Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. It collaborates with research institutes and non-governmental organizations in many countries including Brazil, Canada, Georgia, Germany, India, Israel, Jordan, Norway, the Russian Federation, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The Small Arms Survey occasional paper series presents new and substantial research findings by project staff and commissioned researchers on data, methodological, and conceptual issues related to small arms, or detailed country and regional case studies. The series is published periodically and is available in hard copy and on the project’s web site. Small Arms Survey Phone: + 41 22 908 5777 Graduate Institute of International Studies Fax: + 41 22 732 2738 47 Avenue Blanc Email: [email protected] 1202 Geneva Web site: http://www.smallarmssurvey.org Switzerland ii Occasional Papers No. 1 Re-Armament in Sierra Leone: One Year After the Lomé Peace Agreement, by Eric Berman, December 2000 No. 2 Removing Small Arms from Society: A Review of Weapons Collection and Destruction Programmes, by Sami Faltas, Glenn McDonald, and Camilla Waszink, July 2001 No. -

Mathilde Pierre Weak Judicial Systems And

Mathilde Pierre Weak Judicial Systems and Systematic Sexual Violence against Women and Girls: The Socially Constructed Vulnerability of Female Bodies in Haiti This thesis has been submitted on this day of April 16, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the degree requirements for the NYU Global Liberal Studies Bachelor of Arts degree. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor Emily Bauman, who has guided me through every step in the year-long process of writing my thesis. The time and energy she invested in thoroughly reading and commenting on my work, in recommending other avenues of further research, and in pushing me to deepen my analysis were truly invaluable. I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Joyce Apsel who, although abroad in Florence, Italy, set aside time to speak with me over Skype, to comment on my rough draft, and to advise me on the approach of my argument in my thesis. I would additionally like to thank all of the individuals who set aside considerable time to meet with me for interviews in Port-au-Prince, most notably Attorney Claudy Gassant, Attorney Rosy Auguste, Attorney Marie Alice Belisaire, Attorney Giovanna Menard, Judge Jean Wilner Morin, Carol Pierre-Paul Jacob, Marie Yolaine Gilles, and Officer Guerson Joseph. Finally I extend a heartfelt thank you to my parents, Mathias and Gaëlle Pierre, who greatly assisted in connecting me with the individuals I interviewed and whose constant support and encouragement helped me to push through in the completion of my thesis. 1 ABSTRACT Widespread sexual violence against women and girls in Haiti is a phenomenon that largely persists due to a failure to prosecute male perpetrators and enforce the domestic and international laws that exist to criminalize rape. -

BEYOND-SHOCK-Nov-2012-Report-On-GBV-Progress

BEYOND SHOCK Charting the landscape of sexual violence in post-quake Haiti: Progress, Challenges & Emerging Trends 2010-2012 Anne-christine d’Adesky with PotoFanm+Fi Foreword by Edwidge Danticat | Photo essay by Nadia Todres November 2012 www.potofi.org | www.potofanm.org Report Sponsors: Trocaire, World Pulse & Tides Beyond Shock report 11.26 ABRIDGED VERSION (SHORT REPORT) Author: Anne‐christine d’Adesky and the PotoFanm+Fi coalition © PotoFanm+Fi November 2012. All Rights Reserved. www.potofanm.org For information, media inquiries, report copies: Contact: Anne‐christine d’Adesky Report Coordinator, PotoFanm+Fi Email: [email protected] Haiti: +508 | 3438 2315 US: (415) 690‐6199 1 Beyond Shock DEDICATION This report is dedicated to Haitians who are victims of crimes of sexual violence, including those affected after the historic 2010 earthquake. Some died of injuries related to these crimes. Others have committed suicide, unable to bear injustice and further suffering. May they rest in peace. May we continue to seek justice in their names. Let their memory serve as a reminder of the sacredness of every human life and the moral necessity to act with all our means to protect it. It is also dedicated to the survivors who have had the courage to step out of the shadows of shock, pain, suffering, indignity, and silence and into recovery and public advocacy. Their voices guide a growing grassroots movement. We also acknowledge and thank the many individuals and groups in and outside Haiti – community activists, political leaders, health providers, police officers, lawyers, judges, witnesses, caretakers and family members, human rights and gender activists, journalists and educators – who carry the torch. -

The Dreadful Credibility of Absurd Things: a Tendency in Fantasy Theory 1

Mark Bould The Dreadful Credibility of Absurd Things: A Tendency in Fantasy Theory 1 In Britain it has been estimated that 10% of all books sold are fantasy. And of that fantasy, 10% is written by Terry Pratchett. So, do the sums: 1% of all books sold in Britain are written by Terry Pratchett. Coo. 2 Although it is unclear whether, by ‘fantasy’, Butler intends a narrow denition (generic fantasy, i.e., imitation Tolkien heroic or epic fantasy and sword ’n’ sorcery) or a broad denition (the fantastic genres, i.e., generic fantasy, sf (science ction), horror, super- natural gothic, magic realism, etc.), such statistics nonethless make the need for a Marxist theory – or preferably, Marxist theories – of the fantastic self- evident. The last twenty or thirty years have witnessed a remarkable expansion in the study of fantastic texts and genres. Literary studies has embraced the gothic, fairy tales and sf, and screen studies has developed a complex critique of horror and is now beginning 1 With profound thanks to China Miéville, Kathrina Glitre, Greg Tuck – friends, colleagues, comrades. Thanks also to Historical Materialism ’s anonymous readers, and to José B. Monleón for translating a passage from Benito Pérez Galdós’ s The Reason of Unreason (1915) and thereby providing me with a title. 2 Butler 2001, p. 7. Historical Materialism , volume 10:4 (51–88) ©Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2002 Also available online – www.brill.nl 52 Mark Bould to come to terms with sf. However, there is a remarkable absence in all this endeavour. The rst major Marxist sf theorist, Darko Suvin, notoriously described (narrowly-dened) fantasy as ‘just a subliterature of mystication’ and asserted that the ‘[c]ommerical lumping of it into the same category as SF is thus a grave disservice [to sf] and a rampantly socio-pathological phenomenon’. -

Foyle Heritage Audit NI Core Document

Table of Contents Executive Summary i 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................1 1.1 Purpose of Study ................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Objectives of the Audit ......................................................................................... 2 1.3 Project Team ......................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Study Area ............................................................................................................. 5 1.5 Divisions ................................................................................................................ 6 2 Audit Methodology .......................................................................................8 2.1 Identification of Sources ....................................................................................... 8 2.2 Pilot Study Area..................................................................................................... 9 2.3 Selection & Organisation of Data .......................................................................... 9 2.4 Asset Data Sheets ............................................................................................... 11 2.5 Consultation & Establishment of Significance .................................................... 11 2.6 Public Presentation ............................................................................................