Jay Parini, the Last Station

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample Pages

About This Volume Brett Cooke We continue to be surprised by how the extremely rewarding world WKDW/HR7ROVWR\FUHDWHGLVDG\QDPLFVWLOOJURZLQJRQH:KHQWKH Russian writer sat down in 1863 to begin what became War and PeaceKHXWLOL]HGSRUWUDLWVRIfamily members, as well as images RIKLPVHOILQZKDWDW¿UVWFRQVWLWXWHGDOLJKWO\¿FWLRQDOL]HGfamily chronicle; he evidently used the exercise to consider how he and the SUHVHQWVWDWHRIKLVFRXQWU\FDPHWREH7KLVLQYROYHGDUHWKLQNLQJRI KRZKLVSDUHQWV¶JHQHUDWLRQZLWKVWRRGWKH)UHQFKLQYDVLRQRI slightly more than a half century prior, both militarily and culturally. Of course, one thinks about many things in the course of six highly FUHDWLYH \HDUV DQG KLV WH[W UHÀHFWV PDQ\ RI WKHVH LQWHUHVWV +LV words are over determined in that a single scene or even image typically serves several themes as he simultaneously pondered the Napoleonic Era, the present day in Russia, his family, and himself, DVZHOODVPXFKHOVH6HOIGHYHORSPHQWEHLQJWKH¿UVWRUGHUIRUDQ\ VHULRXVDUWLVWZHVHHDQWLFLSDWLRQVRIWKHSURWHDQFKDOOHQJHV7ROVWR\ posed to the contemporary world decades after War and Peace in terms of religion, political systems, and, especially, moral behavior. In other words, he grew in stature. As the initial reception of the QRYHO VKRZV 7ROVWR\ UHVSRQGHG WR WKH FRQVWHUQDWLRQ RI LWV ¿UVW readers by increasing the dynamism of its form and considerably DXJPHQWLQJLWVLQWHOOHFWXDODPELWLRQV,QKLVKDQGV¿FWLRQEHFDPH emboldened to question the structure of our universe and expand our sense of our own nature. We are all much the richer spiritually for his achievement. One of the happy accidents of literary history is that War and Peace and Fyodor 'RVWRHYVN\¶VCrime and PunishmentZHUH¿UVW published in the same literary periodical, The Russian Messenger. )XUWKHUPRUHDV-DQHW7XFNHUH[SODLQVERWKQRYHOVH[SUHVVFRQFHUQ whether Russia should continue to conform its culture to West (XURSHDQ PRGHOV VLPXOWDQHRXVO\ VHL]LQJ RQ WKH VDPH ¿JXUH vii Napoleon Bonaparte, in one case leading a literal invasion of the country, in the other inspiring a premeditated murder. -

Tolstoy's Oak Tree Metaphor

BJPsych Advances (2015), vol. 21, 185–187 doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.114.013490 Tolstoy’s oak tree metaphor: MINDREADING depression, recovery and psychiatric ‘spiritual ecology’ Jeremy Holmes times for Leo. They had 13 children. However, Jeremy Holmes is a retired SUMMARY with Tolstoy’s increasing fame, accumulated consultant medical psychotherapist and general psychiatrist. He is Tolstoy’s life and work illustrate resilience, disciples and hangers-on, and eccentric views the transcendence of trauma and the enduring currently Visiting Professor to (e.g. on marital celibacy – a precept he signally the Department of Psychology, impact of childhood loss. I have chosen the failed to practise!) the marriage deteriorated, University of Exeter, UK. famous oak tree passage from War and Peace to often into open warfare, and was beset by Correspondence Jeremy Holmes, illustrate recovery from the self-preoccupation of School of Psychology, University of depression and the theme of ‘eco-spirituality’ – Sophia’s suicide threats (Fig 2). At the age of 82, Exeter, Exeter EX4 4QG, UK. Email: the idea that post-depressive connectedness and possibly in the early stages of a confusional state, [email protected] love apply not just to significant others but also to Tolstoy precipitously left home, accompanied by nature and the environment. his daughter Alexandra. A day later he died of pneumonia at Astapovo railway station en route DECLARATION OF INTEREST to the Caucasus. None. War and Peace I seem to re-read War and Peace roughly every Leo Tolstoy’s novels War and Peace (1869) 20 years – my fourth cycle is fast approaching. -

The Last Station

Mongrel Media Presents The Last Station A Film by Michael Hoffman (112 min, Germany, Russia, UK, 2009) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html THE LAST STATION STARRING HELEN MIRREN CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER PAUL GIAMATTI ANNE-MARIE DUFF KERRY CONDON and JAMES MCAVOY WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY MICHAEL HOFFMAN PRODUCED BY CHRIS CURLING JENS MEURER BONNIE ARNOLD *Official Selection: 2009 Telluride Film Festival SYNOPSIS After almost fifty years of marriage, the Countess Sofya (Helen Mirren), Leo Tolstoy’s (Christopher Plummer) devoted wife, passionate lover, muse and secretary—she’s copied out War and Peace six times…by hand!—suddenly finds her entire world turned upside down. In the name of his newly created religion, the great Russian novelist has renounced his noble title, his property and even his family in favor of poverty, vegetarianism and even celibacy. After she’s born him thirteen children! When Sofya then discovers that Tolstoy’s trusted disciple, Chertkov (Paul Giamatti)—whom she despises—may have secretly convinced her husband to sign a new will, leaving the rights to his iconic novels to the Russian people rather than his very own family, she is consumed by righteous outrage. This is the last straw. Using every bit of cunning, every trick of seduction in her considerable arsenal, she fights fiercely for what she believes is rightfully hers. -

Tolstoy's Russia

A tour of TOLSTOY’S RUSSIA 23rd – 27th september 2020 X Map X Introduction from Alexandra Tolstoy As a relative of Leo Tolstoy and having lived in Russia on and off for twenty years, this is a particularly special trip for me. Moscow is a huge, sprawling city, difficult to grasp in a weekend, so for me using one of Russia’s greatest writers as the prism through which to explore is also the ideal way to visit. Tolstoy spent twenty-two winters living and writing in his city home but to completely understand him, and Russian history, we also visit his country estate, Yasnaya Polyana. I have visited both of Tolstoy’s homes many times, also attending family reunions. The houses, preserved as museums, are today exactly as they were in his life time and truly imbibed with his spirit. Moscow, perhaps contrary to expectations, is nowadays one of the world’s most glamorous and vibrant cities, boasting a young, energetic population. As well as being a great cultural and historical centre, the city has a very sophisticated restaurant scene, some of which will be explored on the trip! X 2019 LOCATION ITINERARY HOTEL & MEALS AM: • Recommended flight (not included in quote) London Heathrow – Moscow SVO BA235 10:55/16:50 National Hotel Wednesday 23rd September Moscow PM: Classic Room • You will be met on arrival and transferred to your hotel. • This evening we will enjoy a delicious first meal in Dinner Russia at the Dr Zhivago restaurant in the opulent National Hotel followed by a warming drink on the roof terrace of the Ritz Carlton. -

Becoming Quaker the Friend Independent Quaker Journalism Since 1843

3 February 2017 £1.90 the DISCOVER THE CONTEMPORARYFriend QUAKER WAY Becoming Quaker the Friend INDEPENDENT QUAKER JOURNALISM SINCE 1843 Contents VOL 175 NO 5 3 Thought for the Week: Faith and scepticism John Anderson Freethinkers 4-5 News ‘Freethinkers are those 6-7 Newark Meeting who are willing to use their minds without prejudice Chris Rose and without fearing to 8-9 Letters understand things that clash with their own customs, 10-11 The Chertkov archives privileges, or beliefs. Daphne Sanders 12 Becoming Quaker ‘This state of mind is not common, but it is essential Alex Thomson for right thinking; where 13 Quakerism and spiritual awakening it is absent, discussion is John Elford apt to become worse than useless.’ 14 Out of the silence Rosalind Smith Leo Tolstoy 15 q-eye: a look at the Quaker world 16 Friends & Meetings Cover image: Frost on a fallen leaf. Photo: @notnixon / flickr CC. The Friend Subscriptions Advertising Editorial UK £84 per year by all payment Advertisement manager: Editor: types including annual direct debit; George Penaluna Ian Kirk-Smith monthly payment by direct debit [email protected] £7; online only £66 per year. Articles, images, correspondence For details of other rates, Tel 01535 630230 should be emailed to contact Penny Dunn on 54a Main Street, Cononley [email protected] 020 7663 1178 or [email protected] Keighley BD20 8LL or sent to the address below. the Friend 173 Euston Road, London NW1 2BJ Tel: 020 7663 1010 www.thefriend.org Editor: Ian Kirk-Smith [email protected] • Sub-editor: George Osgerby -

Soft Power» for Russia

A D A L T A JOURNAL OF INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH FICTION AS THE «SOFT POWER» FOR RUSSIA. VISITS AND CONVERSATIONS OF FOREIGN CORRESPONDENTS TO LEO TOLSTOY aLIYA E. BUSHKANETS Karenina» in 1886, «the Death of Ivan Ilyich» in 1887, «Confession» in 1887, «So what should we do?» in 1887, and so Kazan Federal University, doctor of Philological Sciences, on, in three years the American reader has become familiar with Professor, Institute of International Relations. Kremlyovskaya all the main works of Tolstoy), especially religious and ethical St, 18, Kazan, Republic of Tatarstan, 420008, Russia treatises. Translations of Tolstoy's novels «Anna Karenina» and email: [email protected] «Resurrection» caused many critical articles and letters to Tolstoy from European and American readers. The authors of the The work is performed according to the Russian Government Program of Competitive Growth of Kazan Federal University. letters say: before meeting Tolstoy, no writer had ever stirred them with the same force, did not deliver such a high spiritual joy: «I am not able to convey in a letter the delight with which Abstract: This article raises the problem of studying fiction as a «soft power» in the English public met your works. Whatever words I choose, diplomacy. There are such figures in the history of world literature whose works contributed to the spread of the influence of a certain culture or country as a whole to they cannot express my admiration for your books» (Stanley other countries. In Russia, such a figure was Leo Tolstoy. The material of the article Withers. Britain, in 1889); «...Only twelve months ago I got were the reports of European and American correspondents on visits to Tolstoy in the acquainted with your works, read «Resurrection» and late 1890-1900 years. -

MEMORY of the WORLD REGISTER Leo Tolstoy's Personal

MEMORY OF THE WORLD REGISTER Leo Tolstoy’s Personal Library and Manuscripts, Photo and Film Collection Russian Federation Ref N° 2010-78 PART A – ESSENTIAL INFORMATION 1 SUMMARY Leo Tolstoy’s personal library, which numbers 22,000 volumes in 40 languages, is one of the largest writer's libraries in the world. The library was founded by three generations of the Volkonskys-Tolstoys families: by Tolstoy’s grandfather Prince Nikolai Volkonsky, by his parents Maria and Nikolai Tolstoy, and of course the greater part of the library was collected by Tolstoy himself. When Tolstoy’s wife, Sophia Tolstaya, arrived at Yasnaya Polyana in 1862, after their marriage, she found only 2 bookcases there. Now, as it was in 1910, there are 25 bookcases and one big coffer. So, most of the books came to the library in the last 50 years of Tolstoy’s life. The oldest book in the library was published in 1613, the latest books – published in 1910, the last year of Tolstoy’s life. There are about 600 books of the XVII-early XIX centuries, most of them belonged to Tolstoy’s father, Count Nikolai Tolstoy. Tolstoy’s library is very rich in subjects. The choice of books Tolstoy was buying was defined by his activities as writer, thinker, and religious prophet. Among the books of Tolstoy’s library there are editions of books and magazines, which were used as sources for War and Peace, Khadzhi-Murat, for the unfinished novels from the epoch of Peter the Great and history of Decembrists, for his books of wisdom Circle of Reading, For Every Day, Path of Life. -

Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy 1828-1910

Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy 1828-1910 1 Yasnaya Polyana Maternal Grandfather N.S. Volkonsky 1753-1821 33 Paternal Grandfather I.A. Tolstoy (1757-1820) 44 Tolstoy’s Father N.I. Tolstoy (1795-1837) 55 Tolstoy as Boy Rules 1847 • Get up early (five o’clock) Go to bed early (nine to ten o’clock) Eat little and avoid sweets Try to do everything by yourself Have a goal for your whole life, a goal for one section of your life, a goal for a shorter period and a goal for the year; a goal for every month, a goal for every week, a goal for every day, a goal for every hour and for every minute, and sacrifice the lesser goal to the greater Keep away from women Kill desire by work Be good, but try to let no one know it Always live less expensively than you might Change nothing in your style of living even if you become ten times richer 77 Daily Schedule • 5 to 6, practical agriculture 6 to 9, letters 9 to 10, drink tea 10 to 11, set copybooks in order 11 to 1, bookkeeping 1 to 1:30, lunch 1:30 to 3, Italian 3 to 5, English 6 to 8, Russian history • Nothing done. 88 Kazan 1844 Tolstoy as Student Caucasus War 1851 Crimean War 1854 Childhood, Boyhood, Youth 1851-1856 13 Tolstoy as Young Dandy Tolstoy in 1860 Sonya Behrs Married 1862 Code • Y.y.a.n.o.h.r.m.t.s.o.m.a.a.t.i.o.h. I.y.f.e.a.f.o.a.m.a.y.s.L.D.m.w.y.s.T. -

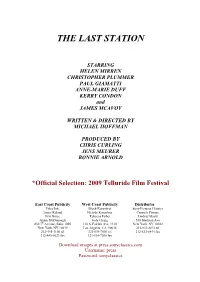

The Last Station

THE LAST STATION STARRING HELEN MIRREN CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER PAUL GIAMATTI ANNE-MARIE DUFF KERRY CONDON and JAMES MCAVOY WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY MICHAEL HOFFMAN PRODUCED BY CHRIS CURLING JENS MEURER BONNIE ARNOLD *Official Selection: 2009 Telluride Film Festival East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Falco Ink. Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Janice Roland Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Erin Bruce Rebecca Fisher Lindsay Macik Annie McDonough Judy Chang 550 Madison Ave 850 7th Avenue, Suite 1005 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 212-445-7100 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 212-445-0623 fax 323-634-7030 fax Download images at press.sonyclassics.com Username: press Password: sonyclassics SYNOPSIS After almost fifty years of marriage, the Countess Sofya (Helen Mirren), Leo Tolstoy’s (Christopher Plummer) devoted wife, passionate lover, muse and secretary—she’s copied out War and Peace six times…by hand!—suddenly finds her entire world turned upside down. In the name of his newly created religion, the great Russian novelist has renounced his noble title, his property and even his family in favor of poverty, vegetarianism and even celibacy. After she’s born him thirteen children! When Sofya then discovers that Tolstoy’s trusted disciple, Chertkov (Paul Giamatti)—whom she despises—may have secretly convinced her husband to sign a new will, leaving the rights to his iconic novels to the Russian people rather than his very own family, she is consumed by righteous outrage. This is the last straw. -

The Gandhi Foundation Multifaith Celebration Contents

The Gandhi Foundation Multifaith Celebration Afternoon of Sunday 30 January or 6 February 2011 Date and time to be confirmed at St Ethelburga’s Centre for Reconciliation and Peace 78 Bishopsgate, London EC2N 4AG (Near Liverpool Street Rail Station, closest underground Aldgate) Theme: Religious Perspectives on the Environment Please confirm details nearer the time from General Inquiries or website as given on back cover of this newsletter Contents A Non-Tourist Indian Experience Denise Moll An Hour with Bapu Keshwar Jahan Hope in Israel-Palestine Trevor Lewis Peace – A Teenager’s View Safia Ahmed The Tolstoy-Gandhi Connection George Paxton Letter: Meeting Gandhi’s closest surviving friend (Felix Padel) Book Reviews: Gandhi’s Interpreter: A Life of Horace Alexander (Geoffrey Carnall) Choice, Liberty and Love: Consciousness in Action (Sheikh Aly N’Daw) Gandhi Foundation News 1 A Non-Tourist Indian Experience Leh, Ladakh & Dehra Dun Denise Moll Heading back for India, after a 3-year gap, I was unexpectedly filled with dread – wasn’t I now too old for this kind of lark?? Then, equally unexpectedly, and with great thankfulness, a calm descended two days before flying …. and remained with me throughout the entire 2 weeks ….. I remained healthy, happy and enabled to live every moment in a way which made me feel very much alive. I was conscious, too, of the great privilege to share in other cultures, religions and be treated as ‘one of the family’. I could only be deeply thankful to the One behind it all. Leh, 11,000 ft high, had suffered a dreadful calamity on 5th August, when, following the worst torrential rain, thunder and lightening ever experienced or remembered in Ladakhi memory, a cloudburst hit the area, with water so violent and ferocious that it swept away everything in its wake …. -

Includes Our Main Attractions and Special Programs 215 345 6789

County Theater 70 PreviewsDECEMBER 2009 – MARCH 2010 Penelope Cruz in BROKEN EMBRACES Cruz in BROKEN Penelope INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTY T HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. When will films play? ADMISSION Main Attractions. Our main films play week-to-week from General ............................................................$9.00 Fridays through Thursdays. Every Monday we determine what Members .........................................................$4.75 new films will start that Friday and what current films will end on Thursday or continue for another week. All of our main Seniors (62+) attraction films are subject to this weekly decision. After we Students (w/ID) & Children (<18). ................$6.75 decide on Mondays, we immediately let you know our plans on Matinees our website, on our hotline, and in our weekly email blast. (For Mon-Fri before 5:00 more info on the business of booking films, visit our website.) Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$6.75 Wed Early Matinee (before 2:30 pm) ...............$4.75 Special Programs. Our special programs are generally Affiliated Theaters Members* ...........................$5.75 scheduled for specific dates and times, which are listed in this Previews brochure and on our website. Make sure that we have your email address *Affiliated Theaters Members We can keep you up-to-date on all of our film scheduling and The County Theater, the Ambler Theater, and the Bryn Mawr events via our weekly email mail notices. Visit our website to Film Institute have reciprocal admission benefits. Your County sign up and then stay plugged into our latest news. -

All the Same the Words Don't Go Away

All the Same The Words Dont Go Away Essays on Authors, Heroes, Aesthetics, and Stage Adaptations from the Russian Tradition Caryl Emerson Caryl Emerson STUDIES IN RUSSIAN AND SLAVIC ARS ROSSIKA LITERATURES, CULTURES AND HISTORY Series Editor: Lazar Fleishman Series Editor: David Bethea (Stanford Universtity) (University of Wisconsin — Madison and Oxford University) All the Same The Words Dont Go Away Essays on Authors, Heroes, Aesthetics, and Stage Adaptations from the Russian Tradition Caryl Emerson Caryl Emerson Boston 2011 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Emerson, Caryl. All the same the words don’t go away : essays on authors, heroes, aesthetics, and stage adaptations from the Russian tradition / Caryl Emerson. p. cm. -- (Studies in Russian and Slavic literatures, cultures and history) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-934843-81-9 (hardback) 1. Russian literature--History and criticism. 2. Russian literature--Adaptations--History and criticism. I. Title. PG2951.E46 2011 891.709--dc22 2010047494 Copyright © 2011 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved Effective May 23, 2016, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. ISBN 978-1-934843-81-9 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-618111-28-9 (electronic) Book design by Ivan Grave On the cover: Saskia Ozols Eubanks, St. Isaac’s Cathedral After the Storm.