Tolstoy's Oak Tree Metaphor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animals Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 2

AAnniimmaallss LLiibbeerraattiioonn PPhhiilloossoopphhyy aanndd PPoolliiccyy JJoouurrnnaall VVoolluummee 55,, IIssssuuee 22 -- 22000077 Animal Liberation Philosophy and Policy Journal Volume 5, Issue 2 2007 Edited By: Steven Best, Chief Editor ____________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Lev Tolstoy and the Freedom to Choose One’s Own Path Andrea Rossing McDowell Pg. 2-28 Jewish Ethics and Nonhuman Animals Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 29-47 Deliberative Democracy, Direct Action, and Animal Advocacy Stephen D’Arcy Pg. 48-63 Should Anti-Vivisectionists Boycott Animal-Tested Medicines? Katherine Perlo Pg. 64-78 A Note on Pedagogy: Humane Education Making a Difference Piers Bierne and Meena Alagappan Pg. 79-94 BOOK REVIEWS _________________ Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal, by Eric Schlosser (2005) Reviewed by Lisa Kemmerer Pg. 95-101 Eternal Treblinka: Our Treatment of Animals and the Holocaust, by Charles Patterson (2002) Reviewed by Steven Best Pg. 102-118 The Longest Struggle: Animal Advocacy from Pythagoras to PETA, by Norm Phelps (2007) Reviewed by Steven Best Pg. 119-130 Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume V, Issue 2, 2007 Lev Tolstoy and the Freedom to Choose One’s Own Path Andrea Rossing McDowell, PhD It is difficult to be sat on all day, every day, by some other creature, without forming an opinion about them. On the other hand, it is perfectly possible to sit all day every day, on top of another creature and not have the slightest thought about them whatsoever. -- Douglas Adams, Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency (1988) Committed to the idea that the lives of humans and animals are inextricably linked, Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy (1828–1910) promoted—through literature, essays, and letters—the animal world as another venue in which to practice concern and kindness, consequently leading to more peaceful, consonant human relations. -

Unpalatable Pleasures: Tolstoy, Food, and Sex

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Scholarship Languages, Literatures, and Cultures 1993 Unpalatable Pleasures: Tolstoy, Food, and Sex Ronald D. LeBlanc University of New Hampshire - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/lang_facpub Recommended Citation Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel. Tolstoy’s Pierre Bezukhov: A Psychoanalytic Study. London: Bristol Classical Press, 1993. Critiques: Brett Cooke, Ronald LeBlanc, Duffield White, James Rice. Reply: Daniel Rancour- Laferriere. Volume VII, 1994, pp. 70-93. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Languages, Literatures, and Cultures Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW ~·'T'::'1r"'T,n.1na rp.llHlrIP~ a strict diet. There needs to'be a book about food. L.N. Tolstoy times it seems to me as if the Russian is a sort of lost soul. You want to do and yet you can do nothing. You keep thinking that you start a new life as of tomorrow, that you will start a new diet as of tomorrow, but of the sort happens: by the evening of that 'very same you have gorged yourself so much that you can only blink your eyes and you cannot even move your tongue. N.V. Gogol Russian literature is mentioned, one is likely to think almost instantly of that robust prose writer whose culinary, gastronomic and alimentary obsessions--in his verbal art as well as his own personal life- often reached truly gargantuan proportions. -

Sample Pages

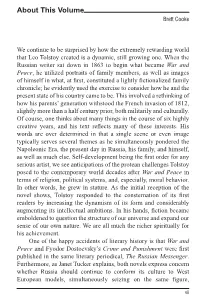

About This Volume Brett Cooke We continue to be surprised by how the extremely rewarding world WKDW/HR7ROVWR\FUHDWHGLVDG\QDPLFVWLOOJURZLQJRQH:KHQWKH Russian writer sat down in 1863 to begin what became War and PeaceKHXWLOL]HGSRUWUDLWVRIfamily members, as well as images RIKLPVHOILQZKDWDW¿UVWFRQVWLWXWHGDOLJKWO\¿FWLRQDOL]HGfamily chronicle; he evidently used the exercise to consider how he and the SUHVHQWVWDWHRIKLVFRXQWU\FDPHWREH7KLVLQYROYHGDUHWKLQNLQJRI KRZKLVSDUHQWV¶JHQHUDWLRQZLWKVWRRGWKH)UHQFKLQYDVLRQRI slightly more than a half century prior, both militarily and culturally. Of course, one thinks about many things in the course of six highly FUHDWLYH \HDUV DQG KLV WH[W UHÀHFWV PDQ\ RI WKHVH LQWHUHVWV +LV words are over determined in that a single scene or even image typically serves several themes as he simultaneously pondered the Napoleonic Era, the present day in Russia, his family, and himself, DVZHOODVPXFKHOVH6HOIGHYHORSPHQWEHLQJWKH¿UVWRUGHUIRUDQ\ VHULRXVDUWLVWZHVHHDQWLFLSDWLRQVRIWKHSURWHDQFKDOOHQJHV7ROVWR\ posed to the contemporary world decades after War and Peace in terms of religion, political systems, and, especially, moral behavior. In other words, he grew in stature. As the initial reception of the QRYHO VKRZV 7ROVWR\ UHVSRQGHG WR WKH FRQVWHUQDWLRQ RI LWV ¿UVW readers by increasing the dynamism of its form and considerably DXJPHQWLQJLWVLQWHOOHFWXDODPELWLRQV,QKLVKDQGV¿FWLRQEHFDPH emboldened to question the structure of our universe and expand our sense of our own nature. We are all much the richer spiritually for his achievement. One of the happy accidents of literary history is that War and Peace and Fyodor 'RVWRHYVN\¶VCrime and PunishmentZHUH¿UVW published in the same literary periodical, The Russian Messenger. )XUWKHUPRUHDV-DQHW7XFNHUH[SODLQVERWKQRYHOVH[SUHVVFRQFHUQ whether Russia should continue to conform its culture to West (XURSHDQ PRGHOV VLPXOWDQHRXVO\ VHL]LQJ RQ WKH VDPH ¿JXUH vii Napoleon Bonaparte, in one case leading a literal invasion of the country, in the other inspiring a premeditated murder. -

![Anna Karenina the Truth of Stories “ How Glorious Fall the Valiant, Sword [Mallet] in Hand, in Front of Battle for Their Native Land.” —Tyrtaeus, Spartan Poet the St](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5886/anna-karenina-the-truth-of-stories-how-glorious-fall-the-valiant-sword-mallet-in-hand-in-front-of-battle-for-their-native-land-tyrtaeus-spartan-poet-the-st-435886.webp)

Anna Karenina the Truth of Stories “ How Glorious Fall the Valiant, Sword [Mallet] in Hand, in Front of Battle for Their Native Land.” —Tyrtaeus, Spartan Poet the St

The CollegeSUMMER 2014 • ST. JOHN’S COLLEGE • ANNAPOLIS • SANTA FE Anna Karenina The Truth of Stories “ How glorious fall the valiant, sword [mallet] in hand, in front of battle for their native land.” —Tyrtaeus, Spartan poet The St. John’s croquet team greets the cheering crowd in Annapolis. ii | The College | st. john’s college | summer 2014 from the editor The College is published by St. John’s College, Annapolis, MD, Why Stories? and Santa Fe, NM [email protected] “ He stepped down, trying not to is not just the suspense, but the connection made Known office of publication: through storytelling that matters: “Storytelling Communications Office look long at her, as if she were ought to be done by people who want to make St. John’s College the sun, yet he saw her, like the other people feel a little bit less alone.” 60 College Avenue In this issue we meet Johnnies who are story- Annapolis, MD 21401 sun, even without looking.” tellers in modern and ancient forms, filmmakers, Periodicals postage paid Leo Tolstoy, ANNA KARENINA poets, even a fabric artist. N. Scott Momaday, at Annapolis, MD Pulitzer Prize winner and artist-in-residence on Postmaster: Send address “Emotions are what pull us in—the character’s the Santa Fe campus, says, “Poetry is the high- changes to The College vulnerabilities, desires, and fears,” says screen- est expression of language.” Along with student Magazine, Communications writer Jeremy Leven (A64); he is one of several poets, he shares insights on this elegant form Office, St. John’s College, 60 College Avenue, alumni profiled in this issue of The College who and how it touches our spirits and hearts. -

Tolstoy and Cosmopolitanism

CHAPTER 8 Tolstoy and Cosmopolitanism Christian Bartolf Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) is known as the famous Russian writer, author of the novels Anna Karenina, War and Peace, The Kreutzer Sonata, and Resurrection, author of short prose like “The Death of Ivan Ilyich”, “How Much Land Does a Man Need”, and “Strider” (Kholstomer). His literary work, including his diaries, letters and plays, has become an integral part of world literature. Meanwhile, more and more readers have come to understand that Leo Tolstoy was a unique social thinker of universal importance, a nineteenth- and twentieth-century giant whose impact on world history remains to be reassessed. His critics, descendants, and followers became almost innu- merable, among them Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in South Africa, later called “Mahatma Gandhi”, and his German-Jewish architect friend Hermann Kallenbach, who visited the publishers and translators of Tolstoy in England and Scotland (Aylmer Maude, Charles William Daniel, Isabella Fyvie Mayo) during the Satyagraha struggle of emancipation in South Africa. The friendship of Gandhi, Kallenbach, and Tolstoy resulted in an English-language correspondence which we find in the Collected Works C. Bartolf (*) Gandhi Information Center - Research and Education for Nonviolence (Society for Peace Education), Berlin, Germany © The Author(s) 2018 121 A.K. Giri (ed.), Beyond Cosmopolitanism, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-5376-4_8 122 C. BARTOLF of both, Gandhi and Tolstoy, and in the Tolstoy Farm as the name of the second settlement project of Gandhi -

Intersemiotic Translation of Russian Classics for Foreign Audiences

Russian Journal of Linguistics 2019 Vol. 23 No. 2 399—414 Вестник РУДН. Серия: ЛИНГВИСТИКА http://journals.rudn.ru/linguistics DOI: 10.22363/2312-9182-2019-23-2-399-414 ∗ “A Sensible Image of the Infinite” : Intersemiotic Translation of Russian Classics for Foreign Audiences Olga Leontovich Volgograd State Socio-Pedagogical University 27 Lenin Prospect, Volgograd, 400066, Russia Tianjin Foreign Studies University No. 117, Machang Road, Hexi Disctrict, Tianjin, China Abstract The article is a continuation of the author’s cycle of works devoted to foreign cinematographic and stage adaptations of Russian classical literature for foreign audiences. The research material includes 17 American, European, Chinese, Indian, Japanese fiction films and TV series, one Broadway musical and 9 Russian films and TV series used for comparison. The paper analyses different theoretical approaches to intersemiotic translation, ‘de-centering of language’ as a modern tendency and intersemiotic translation of literary works in the context of intercultural communication. Key decisions about the interpretation of original texts are made by directors and their teams guided by at least three goals: commercial, creative and ideological. Intersemiotic translation makes use of such strategies as foreignization, domestication and universalization. The resignifying of a literary text by means of the cinematographic semiotic system is connected with such transformations as: a) reduction — omission of parts of the original; b) extension — addition, filling in the blanks, and signifying the unsaid; c) reinterpretation — modification or remodeling of the original in accordance with the director’s creative ideas. A challenge and at the same time one of the key points of intersemiotic translation is a difficult choice between the loyalty to the original, comprehensibility for the target audience and freedom of creativity. -

Tolstoy and Clio: an Exploration in Historiography Through Literature

Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications Pre. 2011 1990 Tolstoy and Clio: An exploration in historiography through literature David Wiles Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks Part of the Russian Literature Commons Wiles, D. (1990). Tolstoy and Clio: An exploration in historiography through literature. Perth, Australia: Edith Cowan University. This Report is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks/7284 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. FACULTY OF HEALTH & HUMAN SCIENCES Centre for the Development of Human Resources TOLSTOY AND CLIO: AN EXPLORATION IN HISTORIOGRAPHY THROUGH LITERATURE David Wiles November 1990 Monograph No.1 ISSN 1037-6224 ISBN 0-7298-0089-X Reprinted November, 1992 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY PERTH WESTERN AUSTRALIA J- 1. -

Bakhtin and Tolstoy

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 9 Issue 1 Special Issue on Mikhail Bakhtin Article 6 9-1-1984 Bakhtin and Tolstoy Ann Shukman Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Russian Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Shukman, Ann (1984) "Bakhtin and Tolstoy," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 9: Iss. 1, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1152 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bakhtin and Tolstoy Abstract This article is a study of the way Bakhtin compared and contrasted Dostoevsky and Tolstoy throughout his career. Special attention is given to Bakhtin's two "Prefaces" of 1929 and 1930 to Resurrection and to the dramas in the Collected Literary Works edition of Tolstoy. Bakhtin's view of Tolstoy is not as narrow as is generally thought. Tolstoy is seen as one of many figures of European literature that make up Bakhtin's literary consciousness. He serves as a point of contrast with Dostoevsky and is described as belonging to an older, more rigid, monologic tradition. Bakhtin's prefaces to Tolstoy's works are not just immanent stylistic analyses but can be seen as well as one of the moments when Bakhtin turns to a sociology of style in the wider sense of examining the social-economic conditions that engender style. -

What to Expect from Lucia Di Lammermoor

WHAT to EXpect From Lucia di Lammermoor The MetropoLitAN OperA’s production OF Lucia di Lammermoor unfurls a tight tapestry of family honor, forbidden love, heart- THE WORK LUCIA DI LAMMERMOOR break, madness, and death. Mary Zimmerman’s exploration of Sir Walter Composed by Gaetano Donizetti Scott’s shocking 1819 novel The Bride of Lammermoor led her down winding roads in Scotland, where her imagination was fed by the country’s untamed Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano vistas and abandoned castles. That journey shaped her ghost-story-inspired (based on The Bride of Lammermoor by Sir Walter Scott) vision for the production of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. The char- First performed on September 26, 1835 acter of Lucia has become an icon in opera and beyond, an archetype of the in Naples, Italy constrained woman asserting herself in society. She reappears as a touchstone for such diverse later characters as Flaubert’s adulterous Madame Bovary THE MET PRODUCTION and the repressed Englishmen in the novels of E.M. Forster. The insanity Marco Armiliato, Conductor that overtakes and destroys Lucia, depicted in opera’s most celebrated mad scene, has especially captured the public imagination. Donizetti’s handling Mary Zimmerman, Production of this fragile woman’s state of mind remains seductively beautiful, thor- Daniel Ostling, Set Designer oughly compelling, and deeply disturbing. Madness as explored in this Mara Blumenfeld, Costume Designer opera is not merely something that happens as a plot function: it is at once a T.J. Gerckens, Lighting Designer personal tragedy, a political statement, and a healing ritual. Daniel Pelzig, Choreographer The tale is set in Scotland, which, to artists of the Romantic era, signi- STARRing fied a wild landscape on the fringe of Europe, with a culture burdened Anna Netrebko (Lucia) by a French-derived code of chivalry and an ancient tribal system. -

Anna Karenina

ANNA KARENINA A musical in 2 acts and 19 scenes. Music, Daniel Levine; Lyrics & Book, Peter Kellogg; Adapted from the novel by Leo Tolstoy; Previewed from Tuesday, 11th August, 1992; Opened in the Circle in the Square Uptown on Wednesday, 26th August , 1992. Closed 4th October, 1992 (46 perfs & 18 previews) THE STORY Act I Anna Karenina, a handsome woman in her late twenties, is visiting her brother, Stiva. She is travelling alone, without husband or son, for the first time. On the train meets a dashing officer, Count Vronsky. Also on the train is Constantin Levin, a brooding intellectual. Levin runs into Stiva at the station confesses he's come to ask Kitty's sister-in-law, to marry him. Stiva warns Levin he has a rival in Vronsky. Stiva greets Anna and we hear the reason for her visit. Stiva has had an affair and his wife, Dolly, has found out. Anna has come to ask Dolly to forgive him, but first she chastises Stiva. The scene changes to the home of eighteen year-old Kitty, whither Dolly has fled. Anna arrives and tells Kitty about seeing Levin. Kitty suspects the reason for his return. Levin then and proposes. Reluctantly Kitty turns him down. Just then, Stiva arrives with Vronsky. Anna comes downstairs, having smoothed things over with Dolly. She recognises Vronsky as the attentive officer from the train. Stiva goes off to speak to Dolly, leaving the other four. A week later, Anna is returning home. At a small station between Moscow and St. Petersburg, Anna steps outside for some air and is surprised to see Count Vronsky. -

1 a Riod a N Te

1 University of Maryland School of Music’s Maryland Opera Studio Presents ARIODANTE Music by George Frideric Handel Libretto by Antonio Salvi KAY THEATRE at The Clarice November 21 - 25, 2019 November PROGRAM University of Maryland School of Music’s Maryland Opera Studio Presents ARIODANTE Music by George Frideric Handel Libretto by Antonio Salvi Performed in Italian, with English Supertitles ABOUT MARYLAND OPERA CAST Ariodante ................................... Esther Atkinson (Nov 22, 25), Jazmine Olwalia (Nov 21, 24) MARYLAND OPERA STUDIO King of Scotland ......................................Jack French (Nov 21, 24), Jeremy Harr (Nov 22, 25) Craig Kier, Director of Maryland Opera Studio Ginevra .............................................. Judy Chirino (Nov 22, 25), Erica Ferguson (Nov 21, 24) Amanda Consol, Director of Acting Justina Lee, Principal Coach | Ashley Pollard, Manager Lurcanio...............................................Charles Calotta (Nov 21, 24) Mike Hogue (Nov 22, 25) Polinesso ..........................................................................................................Jesse Mashburn Dalinda ..........................Michele Currenti (Nov 22, 25), Joanna Zorack-Greene (Nov 21, 24) Odoardo .............................................Charles Calotta (Nov 22, 25), Mike Hogue (Nov 21, 24) ABOUT THE MARYLAND OPERA STUDIO’S CHORUS FALL OPERA PRODUCTION Abigail Beerwart, Andy Boggs, Amanda Densmoor, Henrique Carvalho, Maryland Opera Studio (MOS) singers perform in two fully staged operas. The first of these, -

Tolstoy's Russia

A tour of TOLSTOY’S RUSSIA 23rd – 27th september 2020 X Map X Introduction from Alexandra Tolstoy As a relative of Leo Tolstoy and having lived in Russia on and off for twenty years, this is a particularly special trip for me. Moscow is a huge, sprawling city, difficult to grasp in a weekend, so for me using one of Russia’s greatest writers as the prism through which to explore is also the ideal way to visit. Tolstoy spent twenty-two winters living and writing in his city home but to completely understand him, and Russian history, we also visit his country estate, Yasnaya Polyana. I have visited both of Tolstoy’s homes many times, also attending family reunions. The houses, preserved as museums, are today exactly as they were in his life time and truly imbibed with his spirit. Moscow, perhaps contrary to expectations, is nowadays one of the world’s most glamorous and vibrant cities, boasting a young, energetic population. As well as being a great cultural and historical centre, the city has a very sophisticated restaurant scene, some of which will be explored on the trip! X 2019 LOCATION ITINERARY HOTEL & MEALS AM: • Recommended flight (not included in quote) London Heathrow – Moscow SVO BA235 10:55/16:50 National Hotel Wednesday 23rd September Moscow PM: Classic Room • You will be met on arrival and transferred to your hotel. • This evening we will enjoy a delicious first meal in Dinner Russia at the Dr Zhivago restaurant in the opulent National Hotel followed by a warming drink on the roof terrace of the Ritz Carlton.