An Interview with Anne Tyler Wendy Lamb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suffering and Coping in the Novels of Anne Tyler Camden Story Hastings University of Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2014 Suffering and Coping in the Novels of Anne Tyler Camden Story Hastings University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hastings, Camden Story, "Suffering and Coping in the Novels of Anne Tyler" (2014). Honors Theses. 153. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/153 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUFFERING AND COPING IN THE NOVELS OF ANNE TYLER By Camden Hastings A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2014 Approved By ______________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Kathryn McKee ______________________________________ Reader: Dr. Stephanie Miller ______________________________________ Reader: Dr. Deborah Barker © 2014 Camden Hastings ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii DEDICATION For my mother, who has supported me from the very beginning in all of my endeavors, both academic and otherwise, and who is my hero. For my younger sister, Tinsley, who has encouraged me so often when I needed it the most and who has been a source of many wonderful memories and laughs over the years. For my uncle, A.G. Harmon, who has provided me support, guidance, and inspiration in this and all other parts of my life. -

Honors English II Summer 2017 Assignment Due Monday, August 7, 11:59 Pm Turnitin.Com—Class ID: 15277294 Password: Gocards1

Honors English II Summer 2017 Assignment Due Monday, August 7, 11:59 pm Turnitin.com—Class ID: 15277294 Password: gocards1 Emerson Work Read “An American Scholar” by Ralph Waldo Emerson (available at www.emersoncentral.com/amscholar.htm). Write a brief essay (2-3 pages) about your status as an American scholar. How do you meet Emerson’s criteria? On what aspect of scholarship do you most need to work? Purposes: For your instructor to learn more about you, how you think, what you value, your hopes and expectations For your instructor to appraise your gifts of written expression and to begin to assess areas of focus for honing your skills For you to think about, formulate, and express ideas about both content and the writing process For you to engage in intellectual conversation with peers Format: Word-process in 12 pt Times New Roman, double-spaced Name in upper right corner of page one—no cover page Additional specific instructions for full submission may be given the first week of school Choice Novel Read an independent novel of literary merit that you have not read before. Minimum of 300 pages (may be two books to total over 300 pages). The TWHS English Department recommends that you actually read about 200 pages a week of challenging material to continue growth in reading over the summer; however, we’re just requiring 300 pages for the entire summer. The Scarlet Letter, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, or The Great Gatsby will NOT count for credit for this project. You will need access to the books during that first week or so of school. -

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant: Anne Tyler and the Faulkner Connection

Atlantis Vol. 10 No. 2 Spring' printemps 1985 Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant: Anne Tyler and the Faulkner Connection Mary J. Elkins Florida International University ABSTRACT The structure of Anne Tyler's novel, Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant is interestingly reminiscent of that of William Faulkner's As I Lay Dying; an investigation of the similarities reveals an underlying connection between the two works, a common concern with family dynamics and destinies. Both novelists examine the bonds between people, mysterious bonds beyond or beneath articulation. Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant is not, however, a pale imitation or a contemporary retelling of the Bundren novel. It is a participant in a tradition. The parallels between the two novels are suggestive rather than exact. Despite a certain sharing of Faulkner's fatalism, Tyler gives us characters a bit less passive and events a bit less inexorable. The echoes from Faulkner deepen and intensify the themes of Tyler, but in her novel, for one character at least, obsession ultimately gives way to perspective. The ending is not Faulknerian but Tyler's own; the optimism is limited but unmistakeable. Anne Tyler's latest novel, Dinner to the Home• also named Tull.2 A close look suggests that the sick Restaurant, begins with this sentence, similarities are not limited to names and surface "While Pearl Tull was dying, a funny thought appearances. The structure of Dinner at the occurred to her."1 Pearl does not actually die Homesick Restaurant is reminiscent of that of until the beginning of the last chapter; she "lies As I Lay Dying. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

My Town: Writers on American Cities

MY TOW N WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES MY TOWN WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud .......................................... 2 THE POETRY OF BRIDGES by David Bottoms ........................... 7 GOOD OLD BALTIMORE by Jonathan Yardley .......................... 13 GHOSTS by Carlo Rotella ...................................................... 19 CHICAGO AQUAMARINE by Stuart Dybek ............................. 25 HOUSTON: EXPERIMENTAL CITY by Fritz Lanham .................. 31 DREAMLAND by Jonathan Kellerman ...................................... 37 SLEEPWALKING IN MEMPHIS by Steve Stern ......................... 45 MIAMI, HOME AT LAST by Edna Buchanan ............................ 51 SEEING NEW ORLEANS by Richard Ford and Kristina Ford ......... 59 SON OF BROOKLYN by Pete Hamill ....................................... 65 IN SEATTLE, A NORTHWEST PASSAGE by Charles Johnson ..... 73 A WRITER’S CAPITAL by Thomas Mallon ................................ 79 INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud ore than three-quarters of Americans live in cities. In our globalized era, it is tempting to imagine that urban experiences have a quality of sameness: skyscrapers, subways and chain stores; a density of bricks and humanity; a sense of urgency and striving. The essays in Mthis collection make clear how wrong that assumption would be: from the dreamland of Jonathan Kellerman’s Los Angeles to the vibrant awakening of Edna Buchanan’s Miami; from the mid-century tenements of Pete Hamill’s beloved Brooklyn to the haunted viaducts of Stuart Dybek’s Pilsen neighborhood in Chicago; from the natural beauty and human diversity of Charles Johnson’s Seattle to the past and present myths of Richard Ford’s New Orleans, these reminiscences and musings conjure for us the richness and strangeness of any individual’s urban life, the way that our Claire Messud is the author of three imaginations and identities and literary histories are intertwined in a novels and a book of novellas. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Historical Fiction

Book Group Kit Collection Glendale Library, Arts & Culture To reserve a kit, please contact: [email protected] or call 818-548-2021 New Titles in the Collection — Spring 2021 Access the complete list at: https://www.glendaleca.gov/government/departments/library-arts-culture/services/book-groups-kits American Dirt by Jeannine Cummins When Lydia Perez, who runs a book store in Acapulco, Mexico, and her son Luca are threatened they flee, with countless other Mexicans and Central Americans, to illegally cross the border into the United States. This page- turning novel with its in-the-news presence, believable characters and excellent reviews was overshadowed by a public conversation about whether the author practiced cultural appropriation by writing a story which might have been have been best told by a writer who is Latinx. Multicultural Fiction. 400 pages The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek by Kim Michele Richardson Kentucky during the Depression is the setting of this appealing historical fiction title about the federally funded pack-horse librarians who delivered books to poverty-stricken people living in the back woods of the Appalachian Mountains. Librarian Cussy Mary Carter is a 19-year-old who lives in Troublesome Creek, Kentucky with her father and must contend not only with riding a mule in treacherous terrain to deliver books, but also with the discrimination she suffers because she has blue skin, the result of a rare genetic condition. Both personable and dedicated, Cussy is a sympathetic character and the hardships that she and the others suffer in rural Kentucky will keep readers engaged. -

Book Discussion Schedules 2007

COLUMBIAN BOOK DISCUSSION! SCHEDULE 2006-2007! !July - The Kite Runner by Kahled Hosseini! !August - March by Geraldine Brooks! !September - Digging to America by Anne Tyler! !October - The Devil in the White City by Erik Larson! !November - Peace Like a River by Lefi Enger! !January 4 - The Known World by Edwar P. Jones! !January 25 - Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks! !March 1 - Life of Pi by Yann Martel! !March 25 - My Antonia by Willa Cather! !April - Cold Sassy Tree by Olive Ann Burns! !May - Charming Billy by Alice McDermott! !June - The Atonement by Ian MEwan! ! COLUMBIAN BOOK DISCUSSION! SCHEDULE 2007-2008! !September - Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes! !October - A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khalid Hosseini! !November - Gilead Marilynne Robinson! !January - The Road by Cormac McCarthy! !February - East of Eden by John Steinbeck! !March - Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels! !April - Last Night at the Lobster by Steward O’Nan! !May The Inheritance of Loss by Diran Desai! June - His Illegal Self by Peter Carey! ! ! COLUMBIAN BOOK DISCUSSION! SCHEDULE 2008-2009! !September - Middlemarch by Gearge Eliot! !October - Day by A. L. Kennedy! !November - Cry, the Beloved Country by Alan Paton! !January - The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver! !February - Home by Marilynne Robinson! !March - The Lemon Tree by Sandy Tolan! !April - The vision of Emma Blau by Ursula Hegi! !May - Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston! !June - Crow Lake by Mary Lawson! ! COLUMBIAN BOOK DISCUSSION! SCHEDULE 2009-2010! !September - A Tale of -

Anne Tyler's the Amateur Marriage As a Domestic Tragedy

IRWLE VOL. 10 No. II July 2014 1 Anne Tyler’s The Amateur Marriage as a Domestic Tragedy – A Study Megala Devi American literature in the twentieth century was reshaped by the effects of the Civil rights movement and Women’s Liberation Movements on the American society. The fiction written by women in the twentieth century was the reflection of the position of women in the American culture. Women who wrote modernist fiction were no longer bound within the boundaries established by their predecessors. Changes were implemented in form and content by approaches that were new and focus was more on the expanding world. Women began to write about a number of taboo subjects such as adultery, abortion and divorce, simultaneously exposing the myth of familial perfection. Particularly, Anne Tyler is considered as one of the best novelists of the modern American fiction. Her fiction, focus on dysfunctional family relationships. Critics and reviewers often compare Tyler to the key figures of the South and she is seen as a representative of the Southern Writers. Anne Tyler was born on October 25, 1941 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. She spent her early childhood in various communes in the Midwest and the South with her three younger brothers and her parents, who were active members of the Quaker community and also long-time activists for liberal causes. Initially she was educated at these communes and only at the age of eleven, she attended Public school in Raleigh, North Carolina. Later she attended Duke University on scholarship and graduated from Phi Beta Kappa at the age of nineteen with a degree in Russian. -

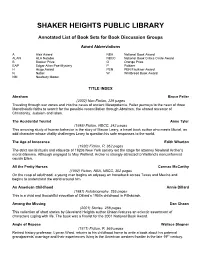

An Annotated Listing of Book Sets

SHAKER HEIGHTS PUBLIC LIBRARY Annotated List of Book Sets for Book Discussion Groups Award Abbreviations A Alex Award NBA National Book Award ALAN ALA Notable NBCC National Book Critics Circle Award B Booker Prize O Orange Prize EAP Edgar Allan Poe-Mystery P Pulitzer H Hugo Award PEN PEN/Faulkner Award N Nobel W Whitbread Book Award NM Newbery Medal TITLE INDEX Abraham Bruce Feiler (2002) Non-Fiction, 229 pages Traveling through war zones and into the caves of ancient Mesopotamia, Feiler journeys to the heart of three Monotheistic faiths to search for the possible reconciliation through Abraham, the shared ancestor of Christianity, Judaism and Islam. The Accidental Tourist Anne Tyler (1985) Fiction, NBCC, 342 pages This amusing study of human behavior is the story of Macon Leary, a travel book author who meets Muriel, an odd character whose vitality challenges Leary to question his safe responses to the world. The Age of Innocence Edith Wharton (1920) Fiction, P, 362 pages The strict social rituals and etiquette of 1920s New York society set the stage for attorney Newland Archer’s moral dilemma. Although engaged to May Welland, Archer is strongly attracted to Welland’s nonconformist cousin Ellen. All the Pretty Horses Cormac McCarthy (1992) Fiction, NBA, NBCC, 302 pages On the cusp of adulthood, a young man begins an odyssey on horseback across Texas and Mexico and begins to understand the world around him. An American Childhood Annie Dillard (1987) Autobiography, 255 pages This is a vivid and thoughtful evocation of Dillard’s 1950s childhood in Pittsburgh. Among the Missing Dan Chaon (2001) Stories, 258 pages This collection of short stories by Cleveland Heights author Chaon features an eclectic assortment of characters coping with life. -

Honors English II Summer 2018 Assignment Due Friday, August 17

Honors English II Summer 2018 Assignment Due Friday, August 17 Emerson Work Read “An American Scholar” by Ralph Waldo Emerson (available at www.emersoncentral.com/amscholar.htm). Write a brief essay (around 500 words) about your status as an American scholar. How do you meet Emerson’s criteria? On what aspect of scholarship do you most need to work? Please note that this assignment is not a summary of Emerson’s speech. It is an essay about you and your understanding of your journey to becoming an American scholar. Purposes: For your instructor to learn more about you, how you think, what you value, your hopes and expectations For your instructor to appraise your gifts of written expression and to begin to assess areas of focus for honing your skills For you to think about, formulate, and express ideas about both content and the writing process For you to engage in intellectual conversation with peers Format: Word-process in 12 pt Times New Roman, double-spaced Name in upper right corner of page one—no cover page Additional specific instructions for full submission will be given the first week of school Choice Novel Read an independent novel of literary merit that you have not read before and that is written by an American author. Your instructor’s decision about what constitutes literary merit is final. Minimum of 300 pages (may be two books to total over 300 pages). The TWHS English Department recommends that you actually read about 200 pages a week of challenging material to continue growth in reading over the summer; however, we’re just requiring 300 pages for the entire summer. -

Best Lists of Iicontemporary" Fiction

BEST LISTS OF IICONTEMPORARY" FICTION In 1~83 the distinguished British novelist and provocateur, Al1thonyBurgcss, decided to issue a list of thp 99 Best Novels in English since WW H. Prc-sumablytht, hundredth slot was available for his readers to add one of his own. IA· :,i1e thisis all merely parlor games on a slightly higher level than "Trivial Ptlrsuit" or "Jcop~rdy", such '~oing~-on do providp somp provocative rcading lists for English Majors and/or people who love to read fiction. So herc arc BurgL'Ss' choices followed by the choices of the CSUS profossors teaching contemporary fiction on a regular basis since thpy were hired. ANTHONY BURGESS· 1939: Party Going by Henry Green. After Many a Summer Dies the Swan by Aldous Huxley. Finnegan's Wake by James Joyce. At Swim-Two-Birds byFlann O'Brien. 1940: The Power & The Glory byGraham Greene.'For Whcml The Bell Tollsby Ernest Hemingway. STRANGERS & BROTHERS(a series of novels to 1970) bye. P. Snow. 1941: The Aerodrome by Rex Wainer. 1944: The Horse's Mouth by Joyce Cary. The Razor's Edge by W. Somerset Maugham 1945.: Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh 1946: Titus Groan by Mervyn Peake 1947: The Victim by Saul Bellow. Under the \Iolcanoby MalcolmLowry 1948: The Heart of the Matter by Graham Greene. The Naked and the Dead by . Norman Mailer. No Highway by Nevil Shute . 1949:The Heat ofthe Day by Elizabeth Bowen, Ape and Essence by Aldous Huxley, 1984 by George OrwelL The Body by William Sansom' 1950: Scenes From Provincial q{e by William Cooper.