National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

River Days Application 2016

FOOD VENDOR APPLICATION 2016 GM River Days 2016 Friday, June 24: 11am – 11pm Saturday, June 25: 11am – 11pm Sunday, June 26: 11am – 9pm ABOUT RIVER DAYS The Detroit RiverFront Conservancy is pleased to present the tenth annual River Days Festival, on Detroit’s internationally acclaimed RiverWalk. In 2015, 150,000 guests enjoyed activities and music that were as diverse as the attendees themselves. River Days takes place at the foot of the Renaissance Center, home to 30,000 employees including a thriving General Motors, and stretches down the RiverWalk to the Milliken State ParK. EVENT COMPONENTS As a unique celebration of the Detroit River and the three-mile RiverWalk, the Festival serves as a regional opportunity to showcase Detroit’s culture and environment. This year, River Days is scheduled to feature: • Three Live music stages including a national talent stage. • Interactive Kids’ Area produced by Detroit’s own Parade Company, located throughout Rivard Plaza adjacent to beautiful Milliken State Park. • The Diamond Jack ferry boat, offering tours of the Detroit River. • Sand sculptures and sand play area for kids. • Jet-ski exhibitions. • Coast Guard Vessels and Rescue Demonstrations. • A family-themed Carnival, games and activities. • Strolling entertainers along the RiverWalk. BENEFITS OF PARTICIPATION • Earn revenue – sell your food items to expected crowds of more than 150,000 guests. • Marketing – generate awareness of your food operation and develop clientele for long after the event is over. Marketing opportunities include: the option to distribute promotional materials at your booth (i.e., coupons, giveaways, etc.), the chance to make live radio appearances, and the opportunity to participate in media interviews. -

Radio Stations in Michigan Radio Stations 301 W

1044 RADIO STATIONS IN MICHIGAN Station Frequency Address Phone Licensee/Group Owner President/Manager CHAPTE ADA WJNZ 1680 kHz 3777 44th St. S.E., Kentwood (49512) (616) 656-0586 Goodrich Radio Marketing, Inc. Mike St. Cyr, gen. mgr. & v.p. sales RX• ADRIAN WABJ(AM) 1490 kHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-1500 Licensee: Friends Communication Bob Elliot, chmn. & pres. GENERAL INFORMATION / STATISTICS of Michigan, Inc. Group owner: Friends Communications WQTE(FM) 95.3 MHz 121 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 265-9500 Co-owned with WABJ(AM) WLEN(FM) 103.9 MHz Box 687, 242 W. Maumee St. (49221) (517) 263-1039 Lenawee Broadcasting Co. Julie M. Koehn, pres. & gen. mgr. WVAC(FM)* 107.9 MHz Adrian College, 110 S. Madison St. (49221) (517) 265-5161, Adrian College Board of Trustees Steven Shehan, gen. mgr. ext. 4540; (517) 264-3141 ALBION WUFN(FM)* 96.7 MHz 13799 Donovan Rd. (49224) (517) 531-4478 Family Life Broadcasting System Randy Carlson, pres. WWKN(FM) 104.9 MHz 390 Golden Ave., Battle Creek (49015); (616) 963-5555 Licensee: Capstar TX L.P. Jack McDevitt, gen. mgr. 111 W. Michigan, Marshall (49068) ALLEGAN WZUU(FM) 92.3 MHz Box 80, 706 E. Allegan St., Otsego (49078) (616) 673-3131; Forum Communications, Inc. Robert Brink, pres. & gen. mgr. (616) 343-3200 ALLENDALE WGVU(FM)* 88.5 MHz Grand Valley State University, (616) 771-6666; Board of Control of Michael Walenta, gen. mgr. 301 W. Fulton, (800) 442-2771 Grand Valley State University Grand Rapids (49504-6492) ALMA WFYC(AM) 1280 kHz Box 669, 5310 N. -

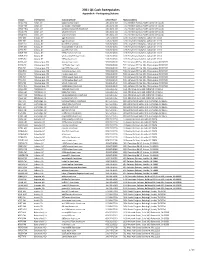

2021 Q1 Cash Sweepstakes Appendix a - Participating Stations

2021 Q1 Cash Sweepstakes Appendix A - Participating Stations Station iHM Market Station Website Office Phone Mailing Address WHLO-AM Akron, OH 640whlo.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-FM Akron, OH sunny1017.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-HD2 Akron, OH cantonsnewcountry.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WKDD-FM Akron, OH wkdd.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WRQK-FM Akron, OH wrqk.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WGY-AM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WGY-FM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WKKF-FM Albany, NY kiss1023.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WOFX-AM Albany, NY foxsports980.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WPYX-FM Albany, NY pyx106.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-FM Albany, NY 995theriver.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-HD2 Albany, NY wildcountry999.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WTRY-FM Albany, NY 983try.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 KABQ-AM Albuquerque, NM abqtalk.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM 87109 KABQ-FM Albuquerque, NM 1047kabq.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM -

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 32 • NUMBER 247 Friday, December 22, 1967 • Washington, D.C

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 32 • NUMBER 247 Friday, December 22, 1967 • Washington, D.C. Pages 20697-20760 Agencies in this issue— Agricultural Research Service Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service Agriculture Department Air Forée Department Atomic Energy Commission Business and Defense Services Administration Civil Aeronautics Board Civil Service Commission Commerce Department Consumer and Marketing Service Emergency Planning Office Farm Credit Administration Federal Aviation Administration Federal Communications Commission Federal Highway Administration Federal Housing Administration Federal Power Commission Federal Trade Commission Fish and Wildlife Service Fiscal Service Interior Department Internal Revenue Service Interstate Commerce Commission Mines Bureau National Aeronautics and Space Administration Navy Department Securities and Exchange Commission Detailed list of Contents appears inside. 2-year Compilation Presidential Documents Code of Federal Regulations TITLE 3, 1964-1965 COMPILATION Contains the full text of Presidential Proclamations, Executive orders, reorganization plans, and other formal documents issued by the President and published in the Federal Register during the period January 1, 1964- December 31, 1965. Includes consolidated tabular finding aids and a consolidated index. Price: $3.75 Compiled by Office of the Federal Register. National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration Order from Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Published daily, Tuesday through Saturday (no publication on Sundays, Mondays, or on the day after an official Federal holiday), by the Office of the Federal Register, National FEDEMUaPEGISTER__ _ Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration (mail address National Area Code 202 - Phone 962-8626 Archives Building, Washington, D.C. 20408), pursuant to the authority contained in the Federal Register Act, approved July 26, 1935 (49 Stat. -

Numbers and Neighborhoods: Seeking and Selling the American Dream in Detroit One Bet at a Time Felicia Bridget George Wayne State University

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2015 Numbers And Neighborhoods: Seeking And Selling The American Dream In Detroit One Bet At A Time Felicia Bridget George Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation George, Felicia Bridget, "Numbers And Neighborhoods: Seeking And Selling The American Dream In Detroit One Bet At A Time" (2015). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 1311. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. NUMBERS AND NEIGHBORHOODS: SEEKING AND SELLING THE AMERICAN DREAM IN DETROIT ONE BET AT A TIME by FELICIA GEORGE DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2015 MAJOR: ANTHROPOLOGY Approved By: Advisor Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project would not have been possible without the support and guidance of a very special group of people. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my committee chair and advisor, Dr. Todd “714” Myers. I cannot express how lucky I was the day you agreed to be my advisor. You planted the seed and it is because of you “Numbers and Neighborhoods” exists. Thank you for your guidance, support, patience, encouragement, and constructive criticism. I cannot thank my other committee members, Dr. Stephen “315” Chrisomalis, Dr. Andrew “240” Newman, and Professor Johnny “631” May enough. -

WDFN, WJLB, WKQI, WLLZ, WMXD, WNIC EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT June 1, 2020 - May 31, 2021

Page: 1/5 WDFN, WJLB, WKQI, WLLZ, WMXD, WNIC EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT June 1, 2020 - May 31, 2021 I. VACANCY LIST See Section II, the "Master Recruitment Source List" ("MRSL") for recruitment source data Recruitment Sources ("RS") RS Referring Job Title Used to Fill Vacancy Hiree Outside Account Executive 1-5, 7, 9-11, 13 3 Outside Account Executive 2, 4-5, 8, 10, 13 8 Sales Support 2, 4-6, 10-11, 13 11 WKQI/Mojo In The Morning On Air/Digital Director 2, 4-5, 9-13 11 Automotive Account Executive 1, 9-11, 13 11 Page: 2/5 WDFN, WJLB, WKQI, WLLZ, WMXD, WNIC EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT June 1, 2020 - May 31, 2021 II. MASTER RECRUITMENT SOURCE LIST ("MRSL") Source Entitled No. of Interviewees RS to Vacancy Referred by RS RS Information Number Notification? Over (Yes/No) Reporting Period All Access 28955 Pacific Coast Hwy Suite 210-5 Malibu, California 90265 1 Url : http://www.allaccess.com N 0 Career Services Manual Posting Direct Employers Association, Inc. 9002 N. Purdue Road Suite 100 Indianapolis, Indiana 46268 2 Phone : 866-268-6206 N 0 Email : [email protected] Fax : 1-317-874-9100 Job Board 3 Employee Referral N 1 iHeartMedia.dejobs.org 20880 Stone Oak Pkwy San Antonio, Texas 78258 4 Phone : 210-253-5126 N 0 Url : http://www.iheartmedia.dejobs.org Talent Acquisition Coordinator Manual Posting iHeartMediaCareers.com 20880 Stone Oak Pkwy San Antonio, Texas 78258 5 Phone : 210-253-5126 N 0 Url : http://www.iheartmediacareers.com Talent Acquisition Coordinator Manual Posting 6 Indeed.com - Not directly contacted by SEU N 1 7 LinkedIn - Not directly contacted by SEU N 1 8 LinkedIn-Not directly contacted by SEU N 1 Radio On-Line 3500 Tripp Avenue Amarillo, Texas 79121-1637 Phone : 806 352-7503 9 Url : http://www.radioonline.com N 0 Email : [email protected] Fax : 1-806-352-3677 Ron Chase Page: 3/5 WDFN, WJLB, WKQI, WLLZ, WMXD, WNIC EEO PUBLIC FILE REPORT June 1, 2020 - May 31, 2021 II. -

11 M , Will U'brlaii and Family, of Leslie

•11 , Will U'Brlaii and family, Of Leslie, S;'-;-..' visited here Buiiday; * •' lOllii Fowler goes to Ohio this week (o make a vIbU aiid brliig; home bis BlstervMay, 'who has beeii visiting friends there the past few weeks. Mrs. Keeler is makliiK some flret* Class evaporated apples at her dryer, ft : ' D. NiBateihan runs his dryer to Its 8ix€rraiid Entertainments! • * - fullest capaoltyi which is twohundred APPLES, dried, per pound . bUBhols per day. i PHILOSOPHER] CHERRIES, dried, per pound The best tea in town. Hoyt Bros. w2 Mrs. Jane Handy. Is visiting ber FEAOBES, dried, per pound.. Editor op the News:—At. the re- ONIONS, perbUBhel Miss Ella Loomis, of Leslie, Is visit Under the new law the election : daughter, Mary VauDeiisert, at Mason. Y011 Know Wliat Pleases You. AGRICUtTURAL SALT, per ton ing Mason friends. boards are requiied to prepare booths cent meeting of the soldiers and sailors Enlereil at the PoatoJ)lce at Maion as Cash paid for produce. Hoyt Bros. Mrs. Ii. Polheoius, who suffered a -TO OPEN WITH- LAND PLASTER, per ton 6 Secand'Clmf viatter. In which to do the voting ou association cf Ingham county, a com stroke of apoplexy two months ago. Is LZVK STOCK AND MEATS. Some miscreant stole two tents from election day, one booth for every 100 rade from Jackson county Mich, made Jay Lane has been In town this week mil HOW falling grudunlly.' i CATTLE, per 100 pounds the courtyard last Week Tuesday night. votes nnd fraction of 25. Below we some statements which provoked some m .2 fioas 00 PUBLISHBO EVKRY TaUBUnAY, BY on business. -

MDOT Michigan State Rail Plan Tech Memo 2 Existing Conditions

Technical Memorandum #2 March 2011 Prepared for: Prepared by: HNTB Corporation Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..............................................................................................................1 2. Freight Rail System Profile ......................................................................................2 2.1. Overview ...........................................................................................................2 2.2. Class I Railroads ...............................................................................................2 2.3. Regional Railroads ............................................................................................6 2.4. Class III Shortline Railroads .............................................................................7 2.5. Switching & Terminal Railroads ....................................................................12 2.7. State Owned Railroads ...................................................................................16 2.8. Abandonments ................................................................................................18 2.10. International Border Crossings .....................................................................22 2.11. Ongoing Border Crossing Activities .............................................................24 2.12. Port Access Facilities ....................................................................................24 3. Freight Rail Traffic ................................................................................................25 -

Press Release

Joye Griffin Toni Thompson UNCF Toni Thompson PR 703-205-3480 Office 310-702-0926 703-483-5398 Mobile [email protected] [email protected] Press Release VIVICA A. FOX, KEVIN FRAZIER, MO’NIQUE, SHEMAR MOORE, SHAUN ROBINSON, AND RAVEN-SYMONÉ AMONG THOSE SCHEDULED TO PRESENT AT UNCF’s A N EVENING OF STARS ® TRIBUTE TO PATTI LABELLE PRESENTED BY TARGET Mario and Big Daddy Kane Join Performers FAIRFAX, Va. (August 27, 2008) – UNCF–the United Negro College Fund– today announced an all-star line-up of presenters and performers scheduled to appear on its 30 th anniversary annual television special, An Evening of Stars ® Tribute to Patti LaBelle . Super Station WGN’s Merri Dee, Vivica A. Fox, Entertainment Tonight correspondent Kevin Frazier, Tom Joyner, BET Chairman and CEO Debra Lee, LisaRaye McCoy, Duane Martin, Mo’Nique, Shemar Moore, Holly Robinson Peete, Access Hollywood’s Shaun Robinson, VH1’s Celebrity Fit Club’s Dr. Ian Smith, Raven Symoné and Essence Cares founder Susan Taylor are among those slated to appear when the annual UNCF celebration of educational excellence is taped on September 13th at the Kodak Theatre in Hollywood. UNCF also announced that Mario and Big Daddy Kane will join fellow performers Yolanda Adams, Anita Baker, Wayne Brady, Fantasia, Jennifer Hudson, Brian McKnight and Dionne Warwick for its salute to Patti LaBelle. Beyoncé, Wyclef Jean and Mariah Carey will make special taped appearances. Patti LaBelle will receive the UNCF’s Award of Excellence for her longtime support of the organization. UNCF supports 60,000 students at 39 institutions and 900 colleges and universities around the country. -

Pan African Agency and the Cultural Political Economy of the Black City: the Case of the African World Festival in Detroit

PAN AFRICAN AGENCY AND THE CULTURAL POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE BLACK CITY: THE CASE OF THE AFRICAN WORLD FESTIVAL IN DETROIT By El-Ra Adair Radney A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree African American and African Studies - Doctor of Philosophy 2019 ABSTRACT PAN AFRICAN AGENCY AND THE CULTURAL POLITICAL ECONOMY OF THE BLACK CITY: THE CASE OF THE AFRICAN WORLD FESTIVAL IN DETROIT By El-Ra Adair Radney Pan African Agency and the Cultural Political Economy of the Black City is a dissertation study of Detroit that characterizes the city as a ‘Pan African Metropolis’ within the combined histories of Black Metropolis theory and theories of Pan African cultural nationalism. The dissertation attempts to reconfigure Saint Clair Drake and Horace Cayton’s Jr’s theorization on the Black Metropolis to understand the intersectional dynamics of culture, politics, and economy as they exist in a Pan African value system for the contemporary Black city. Differently from the classic Black Metropolis study, the current study incorporates African heritage celebration as a major Black life axes in the maintenance of the Black city’s identity. Using Detroit as a case study, the study contends that through their sustained allegiance to African/Afrocentric identity, Black Americans have enhanced the Black city through their creation of a distinctive cultural political economy, which manifests in what I refer to throughout the study as a Pan African Metropolis. I argue that the Pan African Metropolis emerged more visibly and solidified itself during Detroit’s Black Arts Movement in the 1970s of my youth (Thompson, 1999). -

Media Bureau Call Sign Actions 11/15/2017

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission News Media Information 202-418-0500 445 12th St., S.W. Internet: http://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 Report No. 608 Media Bureau Call Sign Actions 11/15/2017 During the period from 10/01/2017 to 10/31/2017 the Commission accepted applications to assign call signs to, or change the call signs of the following broadcast stations. Call Signs Reserved for Pending Sales Applicants Call Sign Service Requested By City State File-Number Former Call Sign KPJK DT RURAL CALIFORNIA BROADCASTING CORPORATION SAN MATEO CA 20171003ACI KCSM-TV KYDQ FM EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION ESCONDIDO CA 20170926AFF KSOQ-FM WKBP FM EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION BENTON PA 20170926AFG WGGI WLJV FM EDUCATIONAL MEDIA FOUNDATION SPOTSYLVANIA VA 20171010ABN WYAU New or Modified Call Signs Row Effective Former Call Call Sign Service Assigned To City State File Number Number Date Sign 1 10/01/2017 KQPV-LP FL ORIENTAL CULTURE CENTER WEST COVINA CA 20131114AWN New 2 10/01/2017 KQSG-LP FL THE EMPEROR'S CIRCLE OF SHEN YUN EL MONTE CA 20131114BOI New 3 10/01/2017 WCHB AM WMUZ RADIO, INC. ROYAL OAK MI WEXL 4 10/01/2017 WMUZ AM WMUZ RADIO, INC. TAYLOR MI WCHB BAL- 5 10/02/2017 KRRD AM OL TIMEY BROADCASTING, LLC FAYETTEVILLE AR KOFC 20170727AFB SALEM MEDIA OF MASSACHUSETTS, 6 10/03/2017 WFIA AM LOUISVILLE KY WJIE LLC DENNIS WALLACE, COURT-APPOINTED 7 10/03/2017 KVMO FM VANDALIA MO KKAC RECEIVER 1 8 10/04/2017 KCCG-LP FL CHURCH OF GOD-GREENVILLE, TX GREENVILLE TX 20131115ASY New BORDERLANDS COMMUNITY MEDIA 9 10/06/2017 KISJ-LP FL BISBEE AZ 20131113BNS New FOUNDATION, INC.