A Case Study of Teesta Low

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments and Coping Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin”

MS “Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments Thesis and Coping Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin” “ Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments and Coping and Induced Critical Moments Flood and of Drought Identification Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin River Lower Teesta Prone Hazard Strategies in This thesis paper is submitted to the department of Geography & Environmental Studies, University of Rajshahi, as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MS - 2015. SUBMITTED BY Roll No. 10116087 Registration No. 2850 Session: 2014 - 15 MS Exam: 2015 ” April, 2017 Department of Geography and Sk. Junnun Sk. Al Third Science Building Environmental Studies, Faculty of Life and Earth Science - Hussain Rajshahi University Rajshahi - 6205 April, 2017 “Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments and Coping Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin” This thesis paper is submitted to the department of Geography & Environmental Studies, University of Rajshahi, as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science - 2015. SUBMITTED BY Roll No. 10116087 Registration No. 2850 Session: 2014 - 15 MS Exam: 2015 April, 2017 Department of Geography and Third Science Building Environmental Studies, Faculty of Life and Earth Science Rajshahi University Rajshahi - 6205 Dedicated To My Family i Declaration The author does hereby declare that the research entitled “Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments and Coping Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin” submitted to the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Rajshahi for the Degree of Master of Science is exclusively his own, authentic and original study. -

Darjeeling Himalayan Railway

ISSUE ONE Darjeeling Himalayan Railway - a brief description Locomotive availability News from the line Chunbhati loop 1943 Birth of the Darjeeling Railway Agony Point, sometime around the 1930's Chunbhati loop - an early view Above the clouds Darjeeling Himalayan Railway Society ISSUE TWO News from the line Darjeeling, past and present Darjeeling station Streamliner Himalayan Mysteries The Causeway Incident Tour to the DHR A Way Forward ISSUE THREE News from the line To Darjeeling - February 98 Locomotive numbers Timetable Vacuum Brakes To Darjeeling in 1966 Darjeeling or Bust Covered Wagons ISSUE FOUR Report: Visit to India in September 1998 Going Loopy (part 1) Loop No1 Loop No2 Chunbhati loop Streamliner (part 2) Jervis Bay Darjeeling's history To School in Darjeeling ISSUE FIVE News from the line Going Loopy (part 2) Batasia loop Gradient profile Riyang station Zigzag No1 In Search of the Darjeeling Tanks Gillanders Arbuthnot & Co Tank Wagon ISSUE SIX News from the line Repairing the breach Going Loopy (part 3) Loop No2 Zigzag No1 to No 6 Tour - the DHRS Measuring a railway curve David Barrie Bullhead rail ISSUE SEVEN News from the line First impressions Bogies Bogie drawing New Jalpaiguri Locomotive and carriage sheds New Jalpaiguri Depot Going Loopy (part 4) Witch of Ghoom Colliery Engines Buffing gear ISSUE EIGHT May 2000 celebrations News from the line Best Kept Station Competition Impressions of Darjeeling - Mary Stickland Tindharia (part1) Tindharia Works Garratt at Chunbhati Going Loopy – Postscript In And Around Darjeeling -

Facilities of White Water Rafting in West Bengal IJPESH 2020; 7(6): 01-03 © 2020 IJPESH Kousik Biswas and Dr

International Journal of Physical Education, Sports and Health 2020; 7(6): 01-03 P-ISSN: 2394-1685 E-ISSN: 2394-1693 Impact Factor (ISRA): 5.38 Facilities of white water rafting in West Bengal IJPESH 2020; 7(6): 01-03 © 2020 IJPESH www.kheljournal.com Kousik Biswas and Dr. Susanta Sarkar Received: 01-09-2020 Accepted: 02-10-2020 Abstract Kousik Biswas The objective of the study was to focus on the existing facilities and scope for White Water Rafting, and Research Scholar, Department of the level of facilities available of standard equipment and training in West Bengal. Checklist interview Physical Education, University and valid official data was analysed during the survey study. Result was found that few Non-Government of Kalyani, Kalyani, Nadia, agencies conducted white water rafting for commercial purpose only. They used both Indian and West Bengal, India international rafting gears but amount of equipment was insufficient, no such Government or Non- Government Institution for White water Rafting training. West Bengal Government do not have any Dr. Susanta Sarkar equipment for White Water Rafting. This study may raise the relevant points which are to be addressed Associate Professor, Department by the appropriate authority to elevate the prospect of White Water Rafting in the state of West Bengal. of Physical Education, University of Kalyani, Kalyani, Keywords: White water rafting, equipment, facilities, West Bengal. Nadia, West Bengal, India Introduction Adventure is an exciting experience that is typically a bold, sometimes risky, undertaking. Adventures may be activities with some potential for physical danger. Engaging ourselves in an unusual and exciting, typically hazardous, experience or activity. -

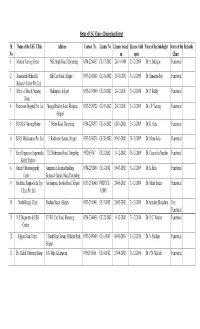

Status of USG Clinic of Darjeeling District Sl

Status of USG Clinic of Darjeeling District Sl. Name of the USG Clinic Address Contact No. License No. License issued License valid Name of the Sonologist Status of the Remarks No. on upto Clinic 1. Mariam Nursing Home N.B. Singh Road, Darjeeling 0354-2254637 CE-17-2002 24-11-1986 31-12-2009 Dr. S. Siddique Functional 2. Anandalok Medical & Hill Cart Road, Siliguri 0353-2510010 CE-18-2002 29-03-2001 31-12-2009 Dr. Shusanta Roy Functional Research Centre Pvt. Ltd. 3. Mitra`s Clinic & Nursing Hakimpara, Siliguri 0353-2431999 CE-23-2002 24-12-2001 31-12-2008 Dr. P. Reddy Functional Home 4. Paramount Hospital Pvt. Ltd. Mangal Panday Road, Khalpara, 0353-2530320 CE-19-2002 28-12-2001 31-12-2009 Dr. J.P. Tayung Functional Siliguri 5. D.D.M.A. Nursing Home 7, Nehru Road, Darjeeling 0354-2254337 CE-16-2002 02-01-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. K. Saha Functional 6. B.B.S. Mediscanner Pvt. Ltd 3, Rashbehari Sarani, Siliguri 0353-2434230 CE-20-2002 09-01-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. Mintu Saha Functional 7. Sono Diagnostic Sagarmatha 7/2/2 Robertson Road, Darjeeling 9832063347 CE-2-2002 13-12-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. Chayanika Nandan Functional Health Enclave 8. Omkar Ultrasonography Anjuman-E-Islamia Building, 0354-2252490 CE-3-2002 05-03-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. K Saha Functional Centre Botanical Garden Road, Darjeeling 9. Suraksha Diagnostic & Eye Ashrampara, Sevoke Road, Siliguri 0353-2530640 PNDT/CE- 28-05-2002 31-12-2009 Dr. Mukti Sarkar Functional Clinic Pvt. -

Rivers of Peace: Restructuring India Bangladesh Relations

C-306 Montana, Lokhandwala Complex, Andheri West Mumbai 400053, India E-mail: [email protected] Project Leaders: Sundeep Waslekar, Ilmas Futehally Project Coordinator: Anumita Raj Research Team: Sahiba Trivedi, Aneesha Kumar, Diana Philip, Esha Singh Creative Head: Preeti Rathi Motwani All rights are reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission from the publisher. Copyright © Strategic Foresight Group 2013 ISBN 978-81-88262-19-9 Design and production by MadderRed Printed at Mail Order Solutions India Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India PREFACE At the superficial level, relations between India and Bangladesh seem to be sailing through troubled waters. The failure to sign the Teesta River Agreement is apparently the most visible example of the failure of reason in the relations between the two countries. What is apparent is often not real. Behind the cacophony of critics, the Governments of the two countries have been working diligently to establish sound foundation for constructive relationship between the two countries. There is a positive momentum. There are also difficulties, but they are surmountable. The reason why the Teesta River Agreement has not been signed is that seasonal variations reduce the flow of the river to less than 1 BCM per month during the lean season. This creates difficulties for the mainly agrarian and poor population of the northern districts of West Bengal province in India and the north-western districts of Bangladesh. There is temptation to argue for maximum allocation of the water flow to secure access to water in the lean season. -

November 26 0 20191126.Pdf

SIkKIM HERALD Vol. 63 No. 75 visit us at www.ipr.sikkim.gov.in Gangtok (Tuesday) November 26, 2019 Regd. No.WB/SKM/01/2017-19 th Sikkim Legislative Assembly Secretariat Governor attends 50 Governor’s Sonam Tshering Marg, Gangtok, Sikkim, 737101 No.259/L&PA Dated:20/11/2019 Conference NOTIFICATION the country was concerned In exercise of the power conferred under Rule16 of the Rules of Governor stressed on its up Procedure and Conduct of Business in Sikkim Legislative Assembly, gradation and expediting Shri L.B.Das, Hon’ble Speaker Sikkim Legislative Assembly has been construction of alternate highway pleased to reconvene a sitting of the House in the Assembly Hall, to Sikkim. This is necessary in view Gangtok on 28th November, 2019 at 11:00 a.m. of Sikkim’s developmental needs, The Hon’ble Members are notified accordingly. tourism and above all, the national security, he said. By order Railway Connectivity: Sd/- Expressing concern and Dr.(Gopal Pd. Dahal) SLASS displeasure about the slow pace Secretary of construction of the much awaited Sevoke-Rangpo Rail Link project, Governor drew the attention of Railway Ministry and Sikkim receives India stressed on its early completion for the benefit of the State and the country as a whole. Today 2019 Awards Air Connectivity: Governor while highlighting the issues and bottlenecks which has halted the flight operations at Pakyong President, Mr. Ram Nath Kovind, Governor Mr. Ganga Prasad, Airport from June 1 this year and th respective Governors and Lt. Governors during the 50 Governor’s the obvious sense of Conference at Rashtrapati Bhawan, New Delhi. -

Chapter 6 Forest Communities & Cprs in the Hill Region

Chapter 6 Forest Communities & CPRs in the Hill Region 6.1 Introduction The region to be studied lies within the Eastern Himalaya which is a biodiversity hotspot little explored as yet by Government scientific agencies like the Botanical Survey of India [BSI] and the Zoological Survey of India [ZSI]. This makes it an important conservation zone, with an approximate area of 15000 sq. km. of forests having already been committed to designated Protected Areas. However imposition of statutory control over regional forests has been accompanied by large scale diversion of forest lands to plantations, agriculture and urban settlement. Economic development has also been accompanied by high levels of immigration which have brought forests in the region under extreme pressure, threatening their very survival. Study of the status of property rights and the patterns of use of CPRs, woodfuels and other forest resources is thus expected to throw light on the interdependence of human communities, economic development and natural resources in a region of the Himalaya where significant forests still survive. By documenting forest access and CPR-use by the communities that live on the very edge of subsistence at the forest fringe~ we make an attempt to meaningfully contribute towards the operationalisation of sustainable development through the means of self-governing social control systems. The present chapter and the next are based on the case-studies undertaken in the two northern districts of Darjeeling and Jalpaiguri in West Bengal respectively. 6.1.1 Geographical Description and Position of the Darjeeling district. Darjeeling is a small district that lies between 26°31' and 27°13' North latitude and between 87° 59' and 88° 53' East longitude in the extreme north of the state of West Bengal in India. -

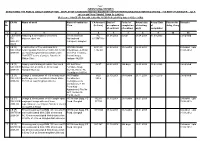

Date of Acceptance of Contract Period of Completion Of

Page 1 (SENSITIZING REPORT) SENSITIZING THE PUBLIC ABOUT CORRUPTION - DISPLAY OF STANDARD NOTICE BOARD BY DEPARTMENTS/ORGANISATION REGARDING : 764 BRTF (P) SWASTIK : JULY 2012 (CONTRACT MORE THAN 50 LAKHS) (Reference HQ CE (P) Swastik letter No.16500/Policy/69/Vig dated 10 Dec 2009) S/ CA No Name of work Name of contractor CA Amount Date of Period of Actual date Actual Date Reason for Remarks No /Firm (In Lacs) acceptance completion of starting of delay, if any of contract of contract work completion 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1 CE(P)/SW Handling & conveyance of cement, The G.M Sikkim Rs. 01.04.2008 1 year 01.04.2008 31.03.2009 Completed TK/ bitumen, steel etc Nationalised 8.17/MT/Km MOT-01/ Transport, Gangtok 08-09 2 CE (P) Construction of Toe walls and RCC M/S Shiv Shakti 2891.21/ 28.08.2008 15 months 02.09.2008 - Extended upto SWTK/02/ retaining walls from Km 24.00 to Km 51.00 Enterprises, A-340/2, 1792.50 31.03.2012 2008-09 on Road Gangtok-Nathula (JNM) under Near P & T Colony, 764 BRTF sector of project Swastik In Shastri Nagar, Sikkim State. Jodhpur-342003 3 CE (P) Supply and stacking of coarse river sand M/s Anil Steel 92.57 29.08.2008 120 days 02.09.2009 15.04.2009 Completed SWTK/03/ between km 24.00 to 51.00 on road Furniture, Shop 2008-09 Gangtok-Nathula No.150, Sector 7C, Chandigarh-160026 4 CE (P) Design & construction of 110 m long major M/S Poddar 892/ 25.10.2008 24 months 24.11.2008 23.11.2010 Completed SWTK/07/ pmt bridge over river Dikchu-Khola at km Construction 899.5 2008-09 31.103 on road Singtham-Dikchu Co;Engineers -

A Case Study of Darjeeling Hill, West Bengal

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 4 Issue 6 ǁ June. 2015ǁ PP.40-48 Landslide along the Highways: A Case Study of Darjeeling Hill, West Bengal. CHIRANJIB NAD. ABSTRACT: Out of the total landslide occurrences, nearly 20% are found in North Eastern region of India. The official figures of United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UN/ISDR) and the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) for the year 2006 also states that landslide ranked third in terms of number of deaths among the top ten natural disasters, as approximately 4 million people were affected by landslides. Unless human death it poses serious damage on roadways, railways, buildings, dams and many natural resources with untold measure of ecosystem and human society. As transportation is a lifeline of a civilization and lack of self sufficiency of a region it hold an important place to meet daily needs of human beings of a region. The study route (NH 31 A, NH 55 and SH 12 A) of landlocked Darjeeling district is very much prone to landslide vulnerability. The black memories of previous massive landslide hazard took large impression on the inhabited society. Sometime the district remains isolated island due to breakdown of transportation for a stretch of days in the time of massive landslide along study route. The main objective of the study is to highlight/describe the present situation of landslide zone along three study route. The study also highlight the nature of landslide took place according to their vulnerability scale, type of movement, type of activity, type of distribution and lastly type of style for further management. -

ANSWERED ON:07.12.2004 DEVELOPMENT of NORTH EASTERN REGION Pradhan Shri Dharmendra

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DEVELOPMENT OF NORTH EASTERN REGION LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:1004 ANSWERED ON:07.12.2004 DEVELOPMENT OF NORTH EASTERN REGION Pradhan Shri Dharmendra Will the Minister of DEVELOPMENT OF NORTH EASTERN REGION be pleased to state: (a) the details of schemes formulated in the previous three years for the Development of North Eastern States; (b) the details of funds allocated to each State for these schemes; (c) whether the funds allocated for these schemes have been fully utilized; (d) if not, the reasons therefor; (e) whether the targets set in these schemes have been achieved; (f) if not, the reasons therefor; and (g) the steps taken by the Government in this regard? Answer MINISTER IN THE MINISTRY OF DEVELOPMENT OF NORTH EASTERN REGION (SHRI P.R. KYNDIAH) (a) & (b): The Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region and the North Eastern Council (NEC) sanction and fund projects for the development of North Eastern Region. The State-wise details of projects sanctioned by the Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region under Non Lapsable Central Pool of Resources (NLCPR) and the sector-wise projects sanctioned by NEC during the previous three years are annexed at Annexure-I. (c) (d) (e) & (f): The position of utilization of funds and the progress of implementation is at Annexure-I. The main reasons for underutilization of funds and underachievement of implementation targets are as follows: i) Generally, the State Governments take long time to transfer funds released by Government of India to the implementing/executing agency ii) Due to long rainy season the working season in the North East is limited as compared to the rest of the country. -

Darjeeling.Pdf

0 CONTENT 1. INTRODUCTION............................................................................ Pg. 1-2 2. DISTRICT PROFILE ……………………………………………………………………….. Pg. 3- 4 3. HISTORY OF DISASTER ………………………………………………………………… Pg. 5 - 8 4. DO’S & DON’T’S ………………………………………………………………………….. Pg. 9 – 10 5. TYPES OF HAZARDS……………………………………………………………………… Pg. 11 6. DISTRICT LEVEL & LINE DEPTT. CONTACTS ………….……………………….. Pg. 12 -18 7. SUB-DIVISION, BLOCK LEVEL PROFILE & CONTACTS …………………….. Pg. 19 – 90 8. LIST OF SAR EQUIPMENTS.............................................................. Pg. 91 - 92 1 INTRODUCTION Nature offers every thing to man. It sustains his life. Man enjoys the beauties of nature and lives on them. But he also becomes a victim of the fury of nature. Natural calamities like famines and floods take a heavy toll of human life and property. Man seems to have little chance in fighting against natural forces. The topography of the district of Darjeeling is such that among the four sub-divisions, three sub-divisions are located in the hills where disasters like landslides, landslip, road blockade are often occurred during monsoon. On the other side, in the Siliguri Sub-Division which lies in the plain there is possibility of flood due to soil erosion/ embankment and flash flood. As district of Darjeeling falls under Seismic Zone IV the probability of earthquake cannot be denied. Flood/ cyclone/ landslide often trouble men. Heavy rains results in rivers and banks overflowing causing damage on a large scale. Unrelenting rains cause human loss. In a hilly region like Darjeeling district poor people do not have well constructed houses especially in rural areas. Because of incessant rains houses collapse and kill people. Rivers and streams overflow inundating large areas. Roads and footpaths are sub merged under water. -

District Disaster Management Plan-2019,Kalimpong

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN-2019,KALIMPONG 1 FOREWORD It is a well-known fact that we all are living in a world where occurrence of disasters whether anthropological or natural are increasing year by year in terms of both magnitude and frequency. Many of the disasters can be attributed to man. We, human beings, strive to make our world comfortable and convenient for ourselves which we give a name ‘development’. However, in the process of development we take more from what Nature can offer and in turn we get more than what we had bargained for. Climate change, as the experts have said, is going to be one major harbinger of tumult to our world. Yet the reason for global warming which is the main cause of climate change is due to anthropological actions. Climate change will lead to major change in weather pattern around us and that mostly will not be good for all of us. And Kalimpong as a hilly district, as nestled in the lap of the hills as it may be, has its shares of disasters almost every year. Monsoon brings landslide and misery to many people. Landslides kill or maim people, kill cattle, destroy houses, destroy crops, sweep away road benches cutting of connectivity and in the interiors rivulets swell making it difficult for people particularly the students to come to school. Hailstorm sometimes destroys standing crops like cardamom resulting in huge loss of revenue. Almost every year lightning kills people. And in terms of earthquake the whole district falls in seismic zone IV. Therefore, Kalimpong district is a multi-hazard prone district and the District Disaster Management Plan is prepared accordingly.