Ulysses Book Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universidade Do Estado Do Rio De Janeiro Centro De Educação E Humanidades Instituto De Letras

Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro Centro de Educação e Humanidades Instituto de Letras Gabriela Romana Viveiros Tipperary, by Frank Delaney: a reading of the rewriting of history in Ireland Rio de Janeiro 2011 Gabriela Romana Viveiros Tipperary, by Frank Delaney: a reading of the rewriting of history in Ireland Dissertação apresentada, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre, ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras, da Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Área de concentração: Literaturas de Língua Inglesa. Orientadora: Prof.a Dra. Ana Lucia de Souza Henriques Rio de Janeiro 2011 CATALOGAÇÃO NA FONTE UERJ/REDE SIRIUS/CEHB D337 Viveiros, Gabriela Romana Tipperary, by Frank Delaney: a reading of the rewriting of history in Ireland / Gabriela Romana Viveiros. - 2011. 79 f. Orientadora: Ana Lucia de Souza Henriques. Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Instituto de Letras. 1. Delaney, Frank, 1942- - Crítica e interpretação – Teses. 2. Delaney, Frank, 1942-. Tipperary – Teses. 3. Ficção irlandesa – História e crítica – Teses. 4. Memória na literatura – Teses. 5. Literatura e história – Irlanda – Teses. I. Henriques, Ana Lucia de Souza. II. Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Instituto de Letras. III. Título. CDU 820(417)-95 Autorizo, apenas para fins acadêmicos e científicos, a reprodução total ou parcial desta dissertação, desde que citada a fonte. __________________________ __________________ Assinatura Data Gabriela Romana Viveiros Tipperary, by Frank Delaney: a reading of the rewriting of history in Ireland Dissertação apresentada, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre, ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras, da Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. -

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries Call Number Author Title Item Enum Copy # Publisher Date of Publication BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.1 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.2 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.3 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.4 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.5 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. PG3356 .A55 1987 Alexander Pushkin / edited and with an 1 Chelsea House 1987. introduction by Harold Bloom. Publishers, LA227.4 .A44 1998 American academic culture in transformation : 1 Princeton University 1998, c1997. fifty years, four disciplines / edited with an Press, introduction by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske ; foreword by Stephen R. Graubard. PC2689 .A45 1984 American Express international traveler's 1 Simon and Schuster, c1984. pocket French dictionary and phrase book. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 1 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 2 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. DS155 .A599 1995 Anatolia : cauldron of cultures / by the editors 1 Time-Life Books, c1995. of Time-Life Books. BS440 .A54 1992 Anchor Bible dictionary / David Noel v.1 1 Doubleday, c1992. -

Bloomsday 2018 Program and Readers List

ULYSSES ULYSSES : CHAPTER-BY-CHAPTER The Rosenbach honors the memory of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses, published in 1922, is one of the most challenging and An irreverent, simple chapter-by-chapter guide to the key events, characters, and rewarding works of English literature. On the surface, the book follows the story of Homeric parallels in James Joyce’s Ulysses, created by Neil Smith for BBC News Online. FRANK DELANEY three central characters—Stephen Dedalus, Leopold Bloom, and Leopold’s wife whose gift for sharing James Joyce touched audiences Molly Bloom—on a single day in Dublin. Ulysses is also a modern retelling of Homer’s Chapters 1–3 Chapter 12 a free day-long program Odyssey, with the three main characters serving as modern versions of Telemachus, The first three chapters introduce would- Bloom has an argument with a pub-bore in Philadelphia on several Bloomsdays. of readings from Ulysses, and Penelope. Joyce’s use of language is genius, employing the stream-of- be writer Stephen Dedalus, familiar to whose blinkered anti-Semitism mirrors consciousness technique to reflect on big events through small happenings in everyday Joyce readers from his earlier novel A Homer’s one-eyed Cyclops. Bloom exits, James Joyce’s masterpiece life. The narrative wanders in a way that celebrates the craft, humor, and meaning of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. On closely followed by a cake tin. exploration, thereby imitating the very wandering it depicts. The best way to read Ulysses the morning of June 16, 1904, Stephen BLOOMSDAY COMMUNITY PARTNERS is to let it carry you along, and to return often to the path it has cut through English leaves the disused watchtower he shares Chapter 13 ULYSSES literature, discovering new things along the way each time. -

Michael Shelden Cv

MICHAEL SHELDEN Address: Department of English, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809 Email: [email protected] Website: www.michaelshelden.com Education: Indiana University, Ph.D., 1979 Indiana University, M.A., 1975 University of Nebraska, B.A., 1973 Employment: Assistant Professor of English, Indiana State University, 1979-1984 Associate Professor of English, Indiana State University, 1984-1989 Professor of English, Indiana State University, 1989-present Visiting Professor of English, Indiana University, 1990 Features Writer, Daily Telegraph of London, 1995-2007 Fiction Critic, Baltimore Sun, 1996-2006 Consultant, British Broadcasting Corporation, 1991-1992, BBC 2 film series on the life and art of English novelist Graham Greene Consultant and Broadcast Commentator, French Television Channel 3 documentary on the life of Graham Greene, 1995 1 BOOKS (author and contributor): "Walter Bagehot." Victorian Prose Writers Before 1867. Ed. William Thesing. Detroit: Gale Research Press, 1987. Friends of Promise: Cyril Connolly and the World of Horizon (New York: Harper Collins, 1989; London: Hamish Hamilton, 1989.) Current edition available from Faber & Faber. Orwell: The Authorized Biography (New York: Harper Collins, 1991; London: Heinemann, 1991). Current edition available from Methuen. Excerpt in The Arlington Reader. Ed. Lynn Z. Bloom (Boston and New York; Bedford/St. Martin’s Press, 2004.) Graham Greene: The Man Within (London: Heinemann, 1994). Graham Greene: The Enemy Within (U.S. Edition; New York: Random House, 1995). “Postscript: An Exchange of Letters between David Lodge and Michael Shelden.” David Lodge, The Practice of Writing. New York and London: Penguin Books, 1996. “Behind the Feminist Mystique.” Interview with Betty Friedan. Betty Friedan, Ed. -

James Joyce Interviews and Recollections in the Same Series Morton N

James Joyce Interviews and Recollections In the same series Morton N. Cohen LEWIS CARROLL: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS Philip Collins (editor) DICKENS: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) THACKERAY: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) J. R. Hammond (editor) H. G. WELLS: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS David McLellan (editor) KARL MARX: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS E. H. Mikhail (editor) BRENDAN BEHAN: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) LADY GREGORY: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS OSCAR WILDE: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) W. B. YEATS: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) Harold Ore! (editor) KIPLING: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) Norman Page (editor) BYRON: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS HENRY JAMES: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS D. H. LAWRENCE: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS (2 volumes) TENNYSON: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS DRJOHNSON: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS Martin Ray JOSEPH CONRAD: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS R. C. Terry (editor) TROLLOPE: INTERVIEWS AND RECOLLECTIONS Series Standins Order If you would like to receive future titles in this series as they are published, you can make use of our standing order facility. To place a standing order please contact your bookseller or, in case of difficulty, write to us at the address below with your name and address and the name of the series. Please state with which title you wish to begin your standing order. (If you live outside the UK we may not have the rights for your area, in which case we will forward your order to the publisher concerned.) Standing Order Service, Macmillan Distribution Ud, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG 21 2XS, England. JAMES JOYCE Interviews and Recollections Edited by E. H. MIKHAIL Professor of English University of Lethbridge Foreword by FRANK DELANEY Selection and editorial matter © E. -

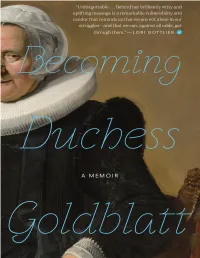

Becoming Duchess Goldblatt Exists Because of Lucy Carson

Contents Title Page Contents Copyright Dedication A Note from Duchess Goldblatt Frontispiece 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Acknowledgments About the Author Connect with HMH Copyright © 2020 by Anonymous All rights reserved For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to [email protected] or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016. hmhbooks.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN 987-0-358-21677-3 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-358-21679-7 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-358-30937-6 (audio) ISBN 978-0-358-30945-1 (compact disc) Wallace Stevens’s definition of poetry is from “Of Modern Poetry,” in Collected Poems. Used by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd. Cover design by Allison Chi Cover art: “Portrait of an Elderly Lady” by Frans Hals, 1633, courtesy of the National Gallery of Art Online Editions. v1.0620 For M. This is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed. Quit hounding me, children. You don’t need to know everything. 1 W I must have slept weird, folks. My backstory is killing me. HEN THE HOUSE burns down, so to speak, there’s no guarantee that anybody will stick around to help sweep up. This is not the dominant narrative I’d been raised to believe in. Sure, Lucy and Ricky could end up divorced—the twin beds were a clue, in hindsight, and he was such a fascist about kicking her out of his stupid nightclub act—but you figure Lucy would always have Ethel Mertz. -

Undergraduate Research and Creativity Expo Program with Abstracts

14th Annual Carolyn & Norwood Thomas Undergraduate Research and Creativity Expo Program with Abstracts Undergraduate Research Week April 20 - 24, 2020 14th Annual Carolyn and Norwood Thomas Undergraduate Research and Creativity Expo 2020 a unit within the University Teaching & Learning Commons utlc.uncg.edu/ursco Preston Lee Phillips Jr, Ph.D. Director Adrienne W. Middlebrooks Business Officer Traci Miller, MSA MARC Program: Academic Enhancement Coordinator Maizie Plumley Graduate Assistant Ali Ramirez Garibay Undergraduate Assistant URSCO is a unit within the University Teaching and Learning Commons University Teaching and Learning Commons 130 Shaw Hall Greensboro, NC 27402-6170 336.334.4776 April 20, 2020 Dear Students, Colleagues, and Guests, I would like to welcome you to the 14th Annual Carolyn and Norwood Thomas Undergraduate Research and Creativity Expo and the 1st ever Virtual Undergraduate Research and Creativity Expo at UNCG. Prior to the realization of the impact COVID-19 would have on the spring semester at UNCG, we were thrilled to accept 266 presentations by more than 335 students, working with 146 mentors, and representing 38 academic departments/programs. As we moved the expo to a virtual platform, we are excited that 183 presentations were submitted. The Undergraduate Research, Scholarship and Creativity Office (URSCO) is dedicated to promoting and supporting student success through mentored undergraduate research, creative inquiry and other scholarly experiences for the UNCG community. The URSCO is also dedicated to helping faculty become increasingly effective with mentoring undergraduate research and integrating research skills into courses and curricula. These experiences can occur in many ways, including co- or extracurricular projects involving one or more students mentored by UNCG faculty. -

Re Joyce Free Ebook

FREERE JOYCE EBOOK Anthony Burgess | 272 pages | 17 Jun 2000 | WW Norton & Co | 9780393004458 | English | New York, United States Get the Stitcher App In this Baker's Dozen essay Frank looks at some of the places in Homer's Greece that connect to Joyce's Dublin. Direct download. Listen to episodes of Frank Delaney's Re: Joyce on Podbay - the best podcast player on the web. ReJOYCE! To commemorate James Joyce's mighty novel. Anthony Burgess's Re Joyce is essential reading for any who undertakes the challenge of reading Joyce. The work contains biography and analysis of all of. ReJOYCE! To commemorate James Joyce's mighty novel, Ulysses, we're launching a podcast. Every week you'll find a five-minute mini-essay from me. Based on the popular podcast of the same name, re:Joyce collects Best-Selling author Frank Delaney's notes on every page of James Joyce's Ulysses. Anthony Burgess's Re Joyce is essential reading for any who undertakes the challenge of reading Joyce. The work contains biography and analysis of all of. Burgess's Re Joyce, then, is the perfect celebration, reflection and survey of the body of work, and a looking forward (through Finnegans Wake) for someone like . Listen to episodes of Frank Delaney's Re: Joyce on Podbay - the best podcast player on the web. ReJOYCE! To commemorate James Joyce's mighty novel. Welcome to Re:Joyce, Frank Delaney's spirited, smart and satisfying deconstruction of James Joyce's Ulysses, in a five-minute podcast. Here is the Introduction. Sep 28, Subscribe. -

Production Drawings and Script Extracts from "Bloom"

Images from Bloom: Production drawings and script extracts from "Bloom" the feature film inspired and adapted from James Joyce's Ulysses, Sean Walsh, Odyssey Pictures Limited, 2004, 0954735927, 9780954735920, 107 pages. this volume provides Production Drawings, Script Extracts and notes From the "Bloom" Feature Film, adapted From James Joyce's Ulysses.. The New Bloomsday Book A Guide Through Ulysses, Harry Blamires, 1996, Literary Criticism, 253 pages. Since 1966 readers new to James Joyce have depended upon this essential guide to Ulysses. Harry Blamires helps readers to negotiate their way through this formidable .... James Joyce's Odyssey a guide to the Dublin of Ulysses, Frank Delaney, Jorge Lewinski, Mar 1, 1982, Literary Criticism, 192 pages. Re-creates Joyce's Dublin of the early twentieth century, comparing it with the modern city, with detailed maps that follow the routes of the principal charachers of "Ulysses .... Ulysses , Margot Norris, 2004, Performing Arts, 102 pages. Margot Norris discusses the challenges that Ulysses, one of the greatest and most difficult novels of the twentieth century, posed to the filmmaker, along with the production .... Picture , Lillian Ross, May 1, 1985, Performing Arts, 240 pages. A Bloomsday postcard , Niall Murphy, Jun 22, 2004, Antiques & Collectibles, 322 pages. Arms and the film war-and-peace in European films, Manuela Gheorghiu-Cernat, 1983, Performing Arts, 322 pages. The Ulysses guide tours through Joyce's Dublin, Robert Nicholson, 2002, History, 179 pages. Follow all eighteen episodes of Ulysses in their original locations with this essential companion for Joyce lovers. Retrace the footsteps of Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom .... Ulysses unbound a reader's companion to James Joyce's Ulysses, Terence Killeen, 2004, Literary Criticism, 258 pages. -

Fiction Core Collection

FICTION CORE COLLECTION A Selection Guide 2013 SUPPLEMENT TO THE SIXTEENTH EDITION EDITED BY EVE-MARIE MILLER, LIZA OLDHAM AND CHRISTI SHOWMAN FARRAR H. W. WILSON A Division of EBSCO Publishing, Inc. IPSWICH, MASSACHUSETTS Copyright © 2013 by H. W. Wilson, A Division of EBSCO Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. For permissions requests, contact [email protected]. Library of Congress Control Number 2009027909 ISBN: 978-0-8242-1103-5 Printed in the United States of America TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface v Directions for Use vi Part 1. List of Fictional Works 1 Part 2. Title and Subject Index 89 PREFACE Fiction Core Collection is a selective list of fiction titles recommended for adult readers. This 2013 Supplement is intended for use with the Sixteenth Edition of the Collection and contains entries for approximately 600 titles. The items in the Collection are considered appropriate for libraries serving adult readers and have been selected with guidance from reviews and the advice of an advisory committee of librarians with special expertise in fiction. This supplement includes both the most popular fiction published in the past year and important new literary and genre titles. Also included are previously published titles filling gaps in genres such as science fiction, romance, and mystery. Although out-of-print titles are eligible for inclusion in Fiction Core Collection, in the belief that good fiction is not obsolete simply because it goes out of print, all titles included in this Supplement were available for purchase at the time of publication. -

Schools and Staff Georgia Department of Education

1989 Georgia Public Education State and Local Schools and Staff Georgia Department of Education Compiled and published by Public Information and Publications Division Office of Department Management Georgia Department of Education Atlanta, Georgia 30334-5010 October 1988 Georgia Board of Education Officers James F. Smith, Chairman Hollis Q. Lathem, Vice Chairman Larry A. Foster Sr., Vice Chairman, Appeals Werner Rogers, Executive Secretary State Superintendent of Schools 2066 Twin Towers East, Atlanta 30334 Members First Congressional District Sixth Congressional District Joe Sears Larry A. Foster Sr. Rt. 1, Nahunta 31553 7989 Fisher Dr., Jonesboro 30236 (912) 264-1857 (404) 478-4000 Term expires January 1995 Term expires January 1992 Second Congressional District Seventh Congressional District Richard C. Owens James F. Smith P.O. Box 174, Ocilla 31774 11 Woodview Dr., Cartersville 30120 (912) 468-7431 (404) 382-6400 Term expires January 1990 Term expires January 1990 Third Congressional District Eighth Congressional District John M. Taylor Albert J. Abrams P.O. Box 1027, LaGrange 30241 P.O. Box 6720, Macon 31208 (404) 882-2501 (912) 741-8010 Term expires January 1990 Term expires January 1995 Fourth Congressional District Ninth Congressional District Juanita Powell Baranco Hollis Q. Lathem 3722 Birchbriar Ct. Rt. 4, Pine Lark Dr., Canton 30114 Decatur 30034 (404) 479-8735 (404) 284-4930 Term expires January 1992 Term expires January 1992 Tenth Congressional District Fifth Congressional District Bobby Carrell Bernadine Cantrell P.O. Box 690, Monroe 30655 4041 Randall Mill Rd. NW, Atlanta 30327 (404) 267-3043 (404) 231-0717 Term expires January 1992 Term expires January 1990 (Note: Members of the Georgia Board of Education are appointed by the Governor for seven-year terms.) 2 FOREWORD This education directory is prepared and distributed annu ally by the Georgia Department of Education as a service to educators and others interested in public education in our state. -

Finnegans Wake As a System of Knowledge Without Primitive Terms: a Proposal Against the Paradigm of Competence in the So-Called Joyce Industry

Finnegans Wake as a System of Knowledge Without Primitive Terms: A Proposal Against the Paradigm of Competence in the So-called Joyce Industry. Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena vorgelegt von Krzysztof Bartnicki, M.A. geboren am 7 V 1971 in Opole, Polen Dissertation, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, 2021 Promotionsfach: Anglistik/Amerikanistik Disputation: 22 VI 2021 Mitglieder der Promotionskommission: Vorsitz: Prof. Dr. Meinolf Vielberg Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Dirk Vanderbeke Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Felix Sprang, Siegen CONTENTS Acknowledgements Introduction 6 1. Chapter 1 – The Referents of the Text of Finnegans Wake 21 1.1. Finnegans Wake as the Set of Texts Recognisable as Finnegans Wake 24 1.2. Finnegans Wake as the 1939 Prototext 28 1.2.1. The Prototext and its Errata of 1945 29 1.2.2. The Prototext’s Post-Joyce Literary Variants 31 1.2.3. Joyce’s Co-Authors of the Prototext 33 1.3. Finnegans Wake as the Model Source Text 36 1.3.1. The Pagination of the Model Source Text 38 1.4. Finnegans Wake as the Macrotext 42 1.5. Finnegans Wake as the Polytext of Source Text-cum-Exegesis 46 1.5.1. The Polytext with the Exegesis-Before-the-Text 47 1.5.2. The Polytext with the Mock Source Text Component 50 1.5.3. The Mock Polytext 51 1.5.4. The Key-Oriented Polytext 51 1.6. Finnegans Wake as the Text in a Model of Reading 53 1.6.1. The Nonsense-Reading Model 57 1.6.2. The Religious Model 60 1.6.3.