Doctor Who, New Dimensions and the Inner World: a Reciprocal Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VORTEX Playing Mrs Constance Clarke

THE BIG FINISH MAGAZINE MARCH 2021 MARCH ISSUE 145 DOCTOR WHO: DALEK UNIVERSE THE TENTH DOCTOR IS BACK IN A BRAND NEW SERIES OF ADVENTURES… ALSO INSIDE TARA-RA BOOM-DE-AY! WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH THEBIGFINISH @BIGFINISHPROD BIGFINISHPROD BIG-FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULL-CAST AUDIO DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND/OR DOWNLOAD WE LOVE STORIES Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers, The Prisoner, The Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain Scarlet, Space: 1999 and Survivors, as well as classics such as HG Wells, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray. We also produce original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield, plus the THE BIG FINISH APP Big Finish Originals range featuring seven great new series: The majority of Big Finish releases ATA Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence can be accessed on-the-go via Investigate, Blind Terror, Transference and The Human Frontier. the Big Finish App, available for both Apple and Android devices. Secure online ordering and details of all our products can be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF EDITORIAL SINCE DOCTOR Who returned to our screens we’ve met many new companions, joining the rollercoaster ride that is life in the TARDIS. We all have our favourites but THE SIXTH DOCTOR ADVENTURES I’ve always been a huge fan of Rory Williams. He’s the most down-to-earth person we’ve met – a nurse in his day job – who gets dragged into the Doctor’s world THE ELEVEN through his relationship with Amelia Pond. -

Doctor Who 50 Jaar Door Tijd En Ruimte

Doctor Who 50 jaar door tijd en ruimte 1963-1989 2005-nu 1963-1989 2005-nu Doctor Who • Britse science fiction Sydney Newman, Verity Lambert, Warris Hussein Doctor Who • Britse science fiction • Moeilijke start • Showrunners • Genre • Studio • Karakter Doctor • 23 november 1963 Doctor Who • Britse science fiction • Show bijna afgevoerd • Educatief kinderprogramma • Tijdreizen = • Toekomst: wetenschap • Verleden: geschiedenis Doctor Who • Britse science fiction • Show bijna afgevoerd • Educatief kinderprogramma • Vier hoofdpersonages • Ian Chesterton • Barbara Wright • Susan Foreman • The Doctor ? Doctor WHO? The Oncoming Storm The Doctor (1963-1966) • Alien • ‚Time Lord’ van planeet Gallifrey • Reist door tijd en ruimte in TARDIS • Vast op aarde met kleindochter William Hartnell - Eerste Doctor Ian, Barbara en Susan TARDIS • ‚Chameleon Circuit’ • Time And Relative Dimension In Space • Eigen zwaartekracht-veld Daleks • Creativiteit op een beperkt budget • Eerste aliens in de show • Planeet Skaro • Aartsvijand Doctor • Culturele invloed • Iconisch uiterlijk Cybermen • Laatste verhaal William Hartnell • Emotieloos • Mens in Cyberman veranderen • ‚Upgrades’ • The Borg Regeneratie Tweede Doctor (1966-1969) • Regeneraties • Van ‚strenge grootvader’ naar ‚kosmische vagebond’ • Twee harten • Sonic screwdriver Patrick Troughton - Tweede Doctor Sonic Screwdriver • Opent sloten, scant omgeving • Kan alles (behalve hout) • Kan te veel? De Time Lords Tweede Doctor (1966-1969) • Regeneraties • Van ‚strenge grootvader’ naar ‚kosmische vagebond’ • Twee harten -

“Living with the Right Focus and Measures” 2 Corinthians 10:12-18 May 6, 2018 Faith Presbyterian Church – Evening Service Pr

“Living with the Right Focus and Measures” 2 Corinthians 10:12-18 May 6, 2018 Faith Presbyterian Church – Evening Service Pr. Nicoletti I’m picking up once more with my series on Second Corinthians tonight. I preached from Hebrews back in March and so it’s been seven months since we last looked at 2 Corinthians. We are up to chapter 10, verses 12-18 tonight. To remind you of what’s going on, at the beginning of chapter 10 there’s a significant shift in tone. Commentator Paul Barnett puts it like this – he says: “It appears that, as the letter draws to its conclusion, Paul’s appeal to the Corinthians becomes more intense emotionally. Like many an orator (and preacher!), he has kept the most urgent and controversial matters until the end and dealt with them passionately so that his last words make their greatest impact on the Corinthians.” [Barnett, 452] The Apostle Paul begins chapter ten by directly confronting some of the accusations his opponents have made against him. We looked at that back in March. Then, in verse 12, he shifts from responding to direct accusations, to highlighting an important difference between him and his opponents. We’ll begin there now – 2 Corinthians 10:12-18. The Apostle Paul writes: 12 Not that we dare to classify or compare ourselves with some of those who are commending themselves. But when they measure themselves by one another and compare themselves with one another, they are without understanding. 13 But we will not boast beyond limits, but will boast only with regard to the area of influence God assigned to us, to reach even to you. -

Bcsfazine #447 • Felicity Walker

The Newsletter of the British Columbia Science Fiction Association #447 $3.00/Issue August 2010 In This Issue: This Month in BCSFA.........................................................0 About BCSFA......................................................................0 Letters of Comment............................................................1 Calendar...............................................................................5 News-Like Matter...............................................................17 Dating Game......................................................................23 Movies: The Man Who Wrote ‘Battlefield: Earth’............24 Media File...........................................................................25 Zines Received..................................................................27 E-Zines Received..............................................................28 Art Credits..........................................................................29 Why You Got This.............................................................29 BCSFAzine © August 2010, Volume 38, #8, Issue #447 is the monthly club newslet- ter published by the British Columbia Science Fiction Association, a social organiza- tion. ISSN 1490-6406. Please send comments, suggestions, and/or submissions to Felicity Walker (the editor), at felicity4711@ gmail .com or #209–3851 Francis Road, Richmond, BC, Canada, V7C 1J6. BCSFAzine solicits electronic submissions and black-and-white line illustrations in JPG, GIF, BMP, or PSD format, -

<H1>The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes</H1>

The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes "Lover and friend hast thou put far from me, and mine acquaintance into darkness." PSALM lxxxviii. 18 CHAPTER I Robert Bunting and Ellen his wife sat before their dully burning, carefully-banked-up fire. The room, especially when it be known that it was part of a house standing in a grimy, if not exactly sordid, London thoroughfare, was exceptionally clean and well-cared-for. A casual stranger, more particularly one of a Superior class to their own, on suddenly opening the door of that sitting-room; would have thought that Mr. page 1 / 387 and Mrs. Bunting presented a very pleasant cosy picture of comfortable married life. Bunting, who was leaning back in a deep leather arm-chair, was clean-shaven and dapper, still in appearance what he had been for many years of his life--a self-respecting man-servant. On his wife, now sitting up in an uncomfortable straight-backed chair, the marks of past servitude were less apparent; but they were there all the same--in her neat black stuff dress, and in her scrupulously clean, plain collar and cuffs. Mrs. Bunting, as a single woman, had been what is known as a useful maid. But peculiarly true of average English life is the time-worn English proverb as to appearances being deceitful. Mr. and Mrs. Bunting were sitting in a very nice room and in their time--how long ago it now seemed!--both husband and wife had been proud of their carefully chosen belongings. -

Blink by Steven Moffat EXT

Blink by Steven Moffat EXT. WESTER DRUMLINS HOUSE - NIGHT Big forbidding gates. Wrought iron, the works. A big modern padlock on. Through the gates, an old house. Ancient, crumbling, overgrown. Once beautiful - still beautiful in decay. Panning along: on the gates - DANGER, KEEP OUT, UNSAFE STRUCTURE -- The gates are shaking, like someone is climbing them -- -- and then a figure drops into a view on the other side. Straightens up into a close-up. SALLY SPARROW. Early twenties, very pretty, just a bit mad, just a bit dangerous. She's staring at the house, eyes shining. Big naughty grin. SALLY Sexy! And she starts marching up the long gravel drive ... CUT TO: INT. WESTER DRUMLINS HOUSE. HALLWAY - NIGHT The big grand house in darkness, huge sweeping staircase, shuttered window, debris everywhere -- One set of shutters buckles from an impact from the inside, splinters. SALLY SPARROW, kicking her away in -- CUT TO: INT. WESTER DRUMLINS HOUSE. HALLWAY/ROOMS - NIGHT SALLY, clutching a camera. Walks from one room to another. Takes a photograph. Her face: fascinated, loving this creepy old place. Takes another photograph. CUT TO: INT. WESTER DRUMLINS HOUSE. CONSERVATORY ROOM - NIGHT In the conservatory now - the windows looking out on a darkened garden. And a patch of rotting wallpaper catches SALLY'S eye -- 2. High on the wall, just below the picture rail, a corner of wallpaper is peeling away, drooping mournfully down from the wall -- -- revealing writing on the plaster behind. Just two letters we can see - BE - the beginning of a word -- She reaches up on tiptoes and pulls at the hanging frond of wallpaper. -

The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh

THE LETTERS OF VINCENT VAN GOGH ‘Van Gogh’s letters… are one of the greatest joys of modern literature, not only for the inherent beauty of the prose and the sharpness of the observations but also for their portrait of the artist as a man wholly and selessly devoted to the work he had to set himself to’ - Washington Post ‘Fascinating… letter after letter sizzles with colorful, exacting descriptions … This absorbing collection elaborates yet another side of this beuiling and brilliant artist’ - The New York Times Book Review ‘Ronald de Leeuw’s magnicent achievement here is to make the letters accessible in English to general readers rather than art historians, in a new translation so excellent I found myself reading even the well-known letters as if for the rst time… It will be surprising if a more impressive volume of letters appears this year’ — Observer ‘Any selection of Van Gogh’s letters is bound to be full of marvellous things, and this is no exception’ — Sunday Telegraph ‘With this new translation of Van Gogh’s letters, his literary brilliance and his statement of what amounts to prophetic art theories will remain as a force in literary and art history’ — Philadelphia Inquirer ‘De Leeuw’s collection is likely to remain the denitive volume for many years, both for the excellent selection and for the accurate translation’ - The Times Literary Supplement ‘Vincent’s letters are a journal, a meditative autobiography… You are able to take in Vincent’s extraordinary literary qualities … Unputdownable’ - Daily Telegraph ABOUT THE AUTHOR, EDITOR AND TRANSLATOR VINCENT WILLEM VAN GOGH was born in Holland in 1853. -

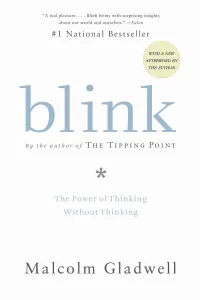

Blink: the Power of Thinking Without Thinking

PENGUIN BOOKS BLINK Author, journalist, cultural commentator and intellectual adventurer, Malcolm Gladwell was born in 1963 in England to a Jamaican mother and an English mathematician father. He grew up in Canada and graduated with a degree in history from the University of Toronto in 1984. From 1987 to 1996, he was a reporter for the Washington Post, first as a science writer and then as New York City bureau chief. Since 1996, he has been a staff writer for the New Yorker magazine. His curiosity and breadth of interests are shown in New Yorker articles ranging over a wide array of subjects including early childhood development and the flu, not to mention hair dye, shopping and what it takes to be cool. His phenomenal bestseller The Tipping Point captured the world’s attention with its theory that a curiously small change can have unforeseen effects, and the phrase has become part of our language, used by writers, politicians and business people everywhere to describe cultural trends and strange phenomena. BLINK The Power of Thinking Without Thinking MALCOLM GLADWELL PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, -

Sociopathetic Abscess Or Yawning Chasm? the Absent Postcolonial Transition In

Sociopathetic abscess or yawning chasm? The absent postcolonial transition in Doctor Who Lindy A Orthia The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia Abstract This paper explores discourses of colonialism, cosmopolitanism and postcolonialism in the long-running television series, Doctor Who. Doctor Who has frequently explored past colonial scenarios and has depicted cosmopolitan futures as multiracial and queer- positive, constructing a teleological model of human history. Yet postcolonial transition stages between the overthrow of colonialism and the instatement of cosmopolitan polities have received little attention within the program. This apparent ‘yawning chasm’ — this inability to acknowledge the material realities of an inequitable postcolonial world shaped by exploitative trade practices, diasporic trauma and racist discrimination — is whitewashed by the representation of past, present and future humanity as unchangingly diverse; literally fixed in happy demographic variety. Harmonious cosmopolitanism is thus presented as a non-negotiable fact of human inevitability, casting instances of racist oppression as unnatural blips. Under this construction, the postcolonial transition needs no explication, because to throw off colonialism’s chains is merely to revert to a more natural state of humanness, that is, cosmopolitanism. Only a few Doctor Who stories break with this model to deal with the ‘sociopathetic abscess’ that is real life postcolonial modernity. Key Words Doctor Who, cosmopolitanism, colonialism, postcolonialism, race, teleology, science fiction This is the submitted version of a paper that has been published with minor changes in The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 45(2): 207-225. 1 1. Introduction Zargo: In any society there is bound to be a division. The rulers and the ruled. -

Five Goes Mad in Stockbridge Fifth Doctor Peter Davison Chats About the New Season

ISSUE #8 OCTOBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE JUDGE DREDD Writer David Bishop on taking another shot at ‘Old Stony Face’ DOCTOR WHO Scribe George Mann on Romana’s latest jaunt FIVE GOES MAD IN STOCKBRIDGE FIFTH DOCTOR PETER DAVISON CHATS ABOUT THE NEW SEASON PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL Hello. More Vortex! Can you believe it? Of course studio session to make sure everyone is happy and that you can, you’re reading this. Now, if I sound a bit everything is running on time. And he has to do all those hyper here, it’s because there’s an incredibly busy time CD Extras interviews. coming up for Big Finish in October. We’ve already started recording the next season of Eighth Doctor What will I be doing? Well, I shall be writing a grand adventures, but on top of that there are more Lost finale for the Eighth Doctor season, doing the sound Stories to come, along with the Sixth Doctor and Jamie design for our three Sherlock Holmes releases, and adventures, the return of Tegan, Holmes and the Ripper writing a brand new audio series for Big Finish, which and more Companion Chronicles than you can shake may or may not get made one day! More news on that a perigosto stick at! So we’ll be in the studio for pretty story later, as they say… much the whole month. I say ‘we’… I actually mean ‘David Richardson’. He’s our man on the spot, at every Nick Briggs – executive producer SNEAK PREVIEWS AND WHISPERS Love Songs for the Shy and Cynical Bernice Summerfield A short story collection by Robert Shearman Secret Histories Rob Shearman is probably best known as a writer for Doctor This year’s Bernice Summerfield book is a short Who, reintroducing the Daleks for its BAFTA winning first stories collection, Secret Histories, a series of series, in an episode nominated for a Hugo Award. -

Doctor Who Party

The Annual DoctorCostume ComparisonWho Gallery Party Tim Harrison, Sr. as the 4th Doctor and Eric Stein as Captain Jack Harkness Jim Martin as the 9th Doctor Sarah Gilbertson as Raffalo (The End of the World) Esther Harrison as Harriet Jones (The Christmas Invasion) Karen Martin as Rose Tyler Jesse Stein as the 10th Doctor Katie Grzebin as Novice Hame (New Earth) Timothy Harrison, Jr. as the 10th Doctor and Lindsay Harrison as Rose Tyler (Tooth and Claw) JoLynn Graubart as Martha Jones and Matt Graubart as a Weeping Angel (Blink) Andrew Gilbertson as Prof. Yana (Utopia) Kayleigh Bickings as Lady Christina (Planet of the Dead) Joe Harrison as a Whifferdill (taking the form of Joe Harrison) (DWM: Voyager) 4, 9, 10, and everyone’s favorite Canine Computer... A bowl of Adipose... No substitute for a sonic blaster, but the 9th and 10th are fans... HOME 2010 The Annual DoctorCostume ComparisonWho Gallery Party Andrew Gilbertson as the 1st Doctor Hayley as a Dalek Camryn Bickings as ...Koquillion? (The Rescue) Timothy Harrison, Jr. as the 5th Doctor Jim Martin as the 9th Doctor Esther Harrison as Sarah Jane Smith BJ Johnson as a Weeping Angel (Blink) Sarah Gilbertson as Lucy Saxon (Last of the Time Lords) Katie Grzebin as Jenny (The Doctor’s Daughter) Karen Martin as the Visionary (The End of Time) Eric Stein as the post-regeneration 11th Doctor (The Eleventh Hour) Joe Harrison as the 11th Doctor Lindsay Harrison as Liz 10 (The Beast Below) JoLynn Graubart as Amy Pond and Matt Graubart as Rory the Roman (The Pandorica Opens) HOME 2009 2011 The Annual DoctorCostume ComparisonWho Gallery Party Andrew Gilbertson as the 2nd Doctor Joe Harrison as Jamie McCrimmon Timothy Harrison, Jr. -

The Pandorica Opens / the Big Bang Sample

The Black Archive #44 THE PANDORICA OPENS / THE BIG BANG SAMPLE By Philip Bates Published June 2020 by Obverse Books Cover Design © Cody Schell Text © Philip Bates, 2020 Range Editors: Paul Simpson, Philip Purser-Hallard Philip Bates has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding, cover or e-book other than which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. Also available #32: The Romans by Jacob Edwards #33: Horror of Fang Rock by Matthew Guerrieri #34: Battlefield by Philip Purser-Hallard #35: Timelash by Phil Pascoe #36: Listen by Dewi Small #37: Kerblam! by Naomi Jacobs and Thomas L Rodebaugh #38: The Sound of Drums / Last of the Time Lords by James Mortimer #39: The Silurians by Robert Smith? #40: The Underwater Menace by James Cooray Smith #41: Vengeance on Varos by Jonathan Dennis #42: The Rings of Akhaten by William Shaw #43: The Robots of Death by Fiona Moore This book is dedicated to my family and friends – to everyone whose story I’m part of. CONTENTS Overview Synopsis Introduction 1: Balancing the Epic and the Intimate 2: Myths and Fairytales 3: Anomalies 4: When Time Travel Wouldn’t Help 5: The Trouble with Time 6: Endings and Beginnings