Conservation of Mass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

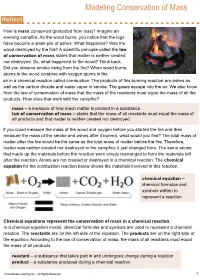

Modeling Conservation of Mass

Modeling Conservation of Mass How is mass conserved (protected from loss)? Imagine an evening campfire. As the wood burns, you notice that the logs have become a small pile of ashes. What happened? Was the wood destroyed by the fire? A scientific principle called the law of conservation of mass states that matter is neither created nor destroyed. So, what happened to the wood? Think back. Did you observe smoke rising from the fire? When wood burns, atoms in the wood combine with oxygen atoms in the air in a chemical reaction called combustion. The products of this burning reaction are ashes as well as the carbon dioxide and water vapor in smoke. The gases escape into the air. We also know from the law of conservation of mass that the mass of the reactants must equal the mass of all the products. How does that work with the campfire? mass – a measure of how much matter is present in a substance law of conservation of mass – states that the mass of all reactants must equal the mass of all products and that matter is neither created nor destroyed If you could measure the mass of the wood and oxygen before you started the fire and then measure the mass of the smoke and ashes after it burned, what would you find? The total mass of matter after the fire would be the same as the total mass of matter before the fire. Therefore, matter was neither created nor destroyed in the campfire; it just changed form. The same atoms that made up the materials before the reaction were simply rearranged to form the materials left after the reaction. -

The First Law of Thermodynamics for Closed Systems A) the Energy

Chapter 3: The First Law of Thermodynamics for Closed Systems a) The Energy Equation for Closed Systems We consider the First Law of Thermodynamics applied to stationary closed systems as a conservation of energy principle. Thus energy is transferred between the system and the surroundings in the form of heat and work, resulting in a change of internal energy of the system. Internal energy change can be considered as a measure of molecular activity associated with change of phase or temperature of the system and the energy equation is represented as follows: Heat (Q) Energy transferred across the boundary of a system in the form of heat always results from a difference in temperature between the system and its immediate surroundings. We will not consider the mode of heat transfer, whether by conduction, convection or radiation, thus the quantity of heat transferred during any process will either be specified or evaluated as the unknown of the energy equation. By convention, positive heat is that transferred from the surroundings to the system, resulting in an increase in internal energy of the system Work (W) In this course we consider three modes of work transfer across the boundary of a system, as shown in the following diagram: Source URL: http://www.ohio.edu/mechanical/thermo/Intro/Chapt.1_6/Chapter3a.html Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/me103#4.1 Attributed to: Israel Urieli www.saylor.org Page 1 of 7 In this course we are primarily concerned with Boundary Work due to compression or expansion of a system in a piston-cylinder device as shown above. -

Law of Conversation of Energy

Law of Conservation of Mass: "In any kind of physical or chemical process, mass is neither created nor destroyed - the mass before the process equals the mass after the process." - the total mass of the system does not change, the total mass of the products of a chemical reaction is always the same as the total mass of the original materials. "Physics for scientists and engineers," 4th edition, Vol.1, Raymond A. Serway, Saunders College Publishing, 1996. Ex. 1) When wood burns, mass seems to disappear because some of the products of reaction are gases; if the mass of the original wood is added to the mass of the oxygen that combined with it and if the mass of the resulting ash is added to the mass o the gaseous products, the two sums will turn out exactly equal. 2) Iron increases in weight on rusting because it combines with gases from the air, and the increase in weight is exactly equal to the weight of gas consumed. Out of thousands of reactions that have been tested with accurate chemical balances, no deviation from the law has ever been found. Law of Conversation of Energy: The total energy of a closed system is constant. Matter is neither created nor destroyed – total mass of reactants equals total mass of products You can calculate the change of temp by simply understanding that energy and the mass is conserved - it means that we added the two heat quantities together we can calculate the change of temperature by using the law or measure change of temp and show the conservation of energy E1 + E2 = E3 -> E(universe) = E(System) + E(Surroundings) M1 + M2 = M3 Is T1 + T2 = unknown (No, no law of conservation of temperature, so we have to use the concept of conservation of energy) Total amount of thermal energy in beaker of water in absolute terms as opposed to differential terms (reference point is 0 degrees Kelvin) Knowns: M1, M2, T1, T2 (Kelvin) When add the two together, want to know what T3 and M3 are going to be. -

Chapter 6. Time Evolution in Quantum Mechanics

6. Time Evolution in Quantum Mechanics 6.1 Time-dependent Schrodinger¨ equation 6.1.1 Solutions to the Schr¨odinger equation 6.1.2 Unitary Evolution 6.2 Evolution of wave-packets 6.3 Evolution of operators and expectation values 6.3.1 Heisenberg Equation 6.3.2 Ehrenfest’s theorem 6.4 Fermi’s Golden Rule Until now we used quantum mechanics to predict properties of atoms and nuclei. Since we were interested mostly in the equilibrium states of nuclei and in their energies, we only needed to look at a time-independent description of quantum-mechanical systems. To describe dynamical processes, such as radiation decays, scattering and nuclear reactions, we need to study how quantum mechanical systems evolve in time. 6.1 Time-dependent Schro¨dinger equation When we first introduced quantum mechanics, we saw that the fourth postulate of QM states that: The evolution of a closed system is unitary (reversible). The evolution is given by the time-dependent Schrodinger¨ equation ∂ ψ iI | ) = ψ ∂t H| ) where is the Hamiltonian of the system (the energy operator) and I is the reduced Planck constant (I = h/H2π with h the Planck constant, allowing conversion from energy to frequency units). We will focus mainly on the Schr¨odinger equation to describe the evolution of a quantum-mechanical system. The statement that the evolution of a closed quantum system is unitary is however more general. It means that the state of a system at a later time t is given by ψ(t) = U(t) ψ(0) , where U(t) is a unitary operator. -

Key Concepts: Conservation of Mass, Momentum, Energy Fluid: a Material

Key concepts: Conservation of mass, momentum, energy Fluid: a material that deforms continuously and permanently under the application of a shearing stress, no matter how small. Fluids are either gases or liquids. (Under very specialized conditions, a phase of intermediate properties can be stable, but we won’t consider that possibility.) In liquids, the molecules are relatively closely spaced, allowing the magnitude of their (attractive, electrically-based) interaction energy to be of the same magnitude as their kinetic energy. As a result, they exist as a loose collection of clusters. In gases, the molecules are much more widely separated, so the kinetic energy (at a given temperature, identical to that in the liquid) is far greater than the interaction energy (much less than in the liquid), and molecule do not form clusters. In a liquid, the molecules themselves typically occupy a few percent of the total space available; in a gas, they occupy a few thousandths of a percent. Nevertheless, for our purposes, all fluids are considered to be continua (no voids or holes).The absence of significant intermolecular attraction allows gases to fill whatever volume is available to them, whereas the presence of such attraction in liquids prevents them from doing so. The attractive forces in liquid water are unusually strong, compared to other liquids. Properties of Fluids: m Density is mass/volume: ρ = . The density of liquid water is V 3 o −3 3 ~1.0 kg/m ; that of air at 20 C is ~1.2x10 kg/m . mg W Specific weight is weight/volume: γ = = = ρg V V C:\Adata\CLASNOTE\342\Class Notes\Key concepts_Topic 1.doc 1 γ Specific gravity is density normalized to the density of water: sg..= i γ w V 1 Specific volume is volume/mass: V = = m ρ Bulk modulus or modulus of elasticity is the pressure change per dp dp fractional change in volume or density: E =− = . -

1. Define Open, Closed, Or Isolated Systems. If You Use an Open System As a Calorimeter, What Is the State Function You Can Calculate from the Temperature Change

CH301 Worksheet 13b Answer Key—Internal Energy Lecture 1. Define open, closed, or isolated systems. If you use an open system as a calorimeter, what is the state function you can calculate from the temperature change. If you use a closed system as a calorimeter, what is the state function you can calculate from the temperature? Answer: An open system can exchange both matter and energy with the surroundings. Δ H is measured when an open system is used as a calorimeter. A closed system has a fixed amount of matter, but it can exchange energy with the surroundings. Δ U is measured when a closed system is used as a calorimeter because there is no change in volume and thus no expansion work can be done. An isolated system has no contact with its surroundings. The universe is considered an isolated system but on a less profound scale, your thermos for keeping liquids hot approximates an isolated system. 2. Rank, from greatest to least, the types internal energy found in a chemical system: Answer: The energy that holds the nucleus together is much greater than the energy in chemical bonds (covalent, metallic, network, ionic) which is much greater than IMF (Hydrogen bonding, dipole, London) which depending on temperature are approximate in value to motional energy (vibrational, rotational, translational). 3. Internal energy is a state function. Work and heat (w and q) are not. Explain. Answer: A state function (like U, V, T, S, G) depends only on the current state of the system so if the system is changed from one state to another, the change in a state function is independent of the path. -

Chapter 15 - Fluid Mechanics Thursday, March 24Th

Chapter 15 - Fluid Mechanics Thursday, March 24th •Fluids – Static properties • Density and pressure • Hydrostatic equilibrium • Archimedes principle and buoyancy •Fluid Motion • The continuity equation • Bernoulli’s effect •Demonstration, iClicker and example problems Reading: pages 243 to 255 in text book (Chapter 15) Definitions: Density Pressure, ρ , is defined as force per unit area: Mass M ρ = = [Units – kg.m-3] Volume V Definition of mass – 1 kg is the mass of 1 liter (10-3 m3) of pure water. Therefore, density of water given by: Mass 1 kg 3 −3 ρH O = = 3 3 = 10 kg ⋅m 2 Volume 10− m Definitions: Pressure (p ) Pressure, p, is defined as force per unit area: Force F p = = [Units – N.m-2, or Pascal (Pa)] Area A Atmospheric pressure (1 atm.) is equal to 101325 N.m-2. 1 pound per square inch (1 psi) is equal to: 1 psi = 6944 Pa = 0.068 atm 1atm = 14.7 psi Definitions: Pressure (p ) Pressure, p, is defined as force per unit area: Force F p = = [Units – N.m-2, or Pascal (Pa)] Area A Pressure in Fluids Pressure, " p, is defined as force per unit area: # Force F p = = [Units – N.m-2, or Pascal (Pa)] " A8" rea A + $ In the presence of gravity, pressure in a static+ 8" fluid increases with depth. " – This allows an upward pressure force " to balance the downward gravitational force. + " $ – This condition is hydrostatic equilibrium. – Incompressible fluids like liquids have constant density; for them, pressure as a function of depth h is p p gh = 0+ρ p0 = pressure at surface " + Pressure in Fluids Pressure, p, is defined as force per unit area: Force F p = = [Units – N.m-2, or Pascal (Pa)] Area A In the presence of gravity, pressure in a static fluid increases with depth. -

Ley De Conservación De La Masa

CULTURA CIENTÍFICA para la Enseñanza Secundaria LEY DE CONSERVACIÓN DE LA MASA: DE LA ALQUIMIA A LA QUÍMICA MODERNA Antoine Laurent Lavoisier Este trabajo ha sido realizado en el marco de un proyecto de investigación docente conce- dido y financiado por el Vicerrectorado de Es- tudiantes y Acción Social y el Vicerrectorado de Investigación de la Universidad Católica de Valencia San Vicente Mártir. CULTURA CIENTÍFICA para la Enseñanza Secundaria Con este proyecto se pretende que los alum- nos de Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria (E.S.O.) adquieran una cultura científica y co- Edita: nozcan que la ciencia, la sociedad y la tecno- UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE VALENCIA logía no se pueden concebir aisladamente. Vicerrectorado de Estudiantes y Acción Social Alumnos y profesores hemos trabajado desde Vicerrectorado de Investigación una perspectiva multidisciplinar a través de Diseño y Maquetación: diferentes asignaturas y Grados Universitarios. Medianil Comunicación / medianil.com Autores: Stephany Cuellar Mosquera Sergio Gómez Molina Mariana Herrán Gonzalez Rocío Navarro Salazar Javier Pérez Murillo María Rojas Chacón José Urpin Rangel Asignatura: Fundamentos básicos de Química Profesor/a: Dra. Ángela Moreno Gálvez Grado: Nutrición Humana y Dietética Coordinadora: Dra. Gloria Castellano Estornell ÉRASE UNA VEZ 3 Descubrimiento de la Ley de conservación de la masa Antes de Lavoisier la Química como de los productos de una reacción ciencia apenas existía. Los cono- química debe ser igual al peso de cimientos que había eran vagos los reactantes, estableciendo que y estaban incluso en ocasiones “la materia ni se crea ni se destru- mezclados con conceptos cercanos ye en cualquier reacción química”, a lo mágico o lo esotérico, según y transformando así la química en la tradición alquímica provenien- ciencia con mayúsculas. -

First Law of Thermodynamics Control Mass (Closed System)

First Law of Thermodynamics Reading Problems 3-2 ! 3-7 3-40, 3-54, 3-105 5-1 ! 5-2 5-8, 5-25, 5-29, 5-37, 5-40, 5-42, 5-63, 5-74, 5-84, 5-109 6-1 ! 6-5 6-44, 6-51, 6-60, 6-80, 6-94, 6-124, 6-168, 6-173 Control Mass (Closed System) In this section we will examine the case of a control surface that is closed to mass flow, so that no mass can escape or enter the defined control region. Conservation of Mass Conservation of Mass, which states that mass cannot be created or destroyed, is implicitly satisfied by the definition of a control mass. Conservation of Energy The first law of thermodynamics states “Energy cannot be created or destroyed it can only change forms”. energy entering - energy leaving = change of energy within the system Sign Convention Cengel Approach Heat Transfer: heat transfer to a system is positive and heat transfer from a system is negative. Work Transfer: work done by a system is positive and work done on a system is negative. For instance: moving boundary work is defined as: Z 2 Wb = P dV 1 During a compression process, work is done on the system and the change in volume goes negative, i.e. dV < 0. In this case the boundary work will also be negative. 1 Culham Approach Using my sign convention, the boundary work is defined as: Z 2 Wb = − P dV 1 During a compression process, the change in volume is still negative but because of the negative sign on the right side of the boundary work equation, the bound- ary work directed into the system is considered positive. -

LAVOISIER-The Crucial Year the Background and Origin of His First

LAVOISIER-THE CRUCIAL YEAR: The Background and Origin of His First Experiments on Combustion in z772 Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, 17 43-1794, a portrait by David (Photo Roger-Viollet) LA VOISIER -The Crucial Year The Background and Origin of His First Experiments on Combustion in 1772 /J_y llenr_y (Juerlac CORNELL UNIVERSITY CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS Ithaca, New York Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. This work has been brought to publication with the assistance of a grant from the Ford Foundation. Copyright © 1961 by Cornell University First paperback printing 2019 The text of this book is li censed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommerciai-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the li cense, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978- 1-501 7-4663-5 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-4664-2 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-4665-9 ( epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress TO Andrew Norman Meldrum (1876-1934) AND Helene Metzger (188g-1944) Acknowledgments MUCH of the research and much of the writing of a first draft of this book was completed while I was a mem ber of the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, in 1953-1955. -

Chapter 9 – Center of Mass and Linear Momentum I

Chapter 9 – Center of mass and linear momentum I. The center of mass - System of particles / - Solid body II. Newton’s Second law for a system of particles III. Linear Momentum - System of particles / - Conservation IV. Collision and impulse - Single collision / - Series of collisions V. Momentum and kinetic energy in collisions VI. Inelastic collisions in 1D -Completely inelastic collision/ Velocity of COM VII. Elastic collisions in 1D VIII. Collisions in 2D IX. Systems with varying mass X. External forces and internal energy changes I. Center of mass The center of mass of a body or a system of bodies is a point that moves as though all the mass were concentrated there and all external forces were applied there. - System of particles: General: m1x1 m2 x2 m1x1 m2 x2 xcom m1 m2 M M = total mass of the system - The center of mass lies somewhere between the two particles. - Choice of the reference origin is arbitrary Shift of the coordinate system but center of mass is still at the same relative distance from each particle. I. Center of mass - System of particles: m2 xcom d m1 m2 Origin of reference system coincides with m1 3D: 1 n 1 n 1 n xcom mi xi ycom mi yi zcom mi zi M i1 M i1 M i1 1 n rcom miri M i1 - Solid bodies: Continuous distribution of matter. Particles = dm (differential mass elements). 3D: 1 1 1 xcom x dm ycom y dm zcom z dm M M M M = mass of the object M Assumption: Uniform objects uniform density dm dV V 1 1 1 Volume density xcom x dV ycom y dV zcom z dV V V V Linear density: λ = M / L dm = λ dx Surface density: σ = M / A dm = σ dA The center of mass of an object with a point, line or plane of symmetry lies on that point, line or plane. -

Study Guide for Oxygen

STUDY GUIDE for OXYGEN By Carl Djerassi and Roald Hoffmann 1 The authors of the play “Oxygen” have distinguished careers as chemists. And they also have a commitment to reaching out to the general public, each in a distinct way, through essays, books, poems, novels, and plays. “Oxygen” is a play they have written together. The play has been performed in the USA, the UK and Germany, and broadcast over UK and German radio. It has also been published in book form in English, and in German translation, by Wiley-VCH. The play and the book serve as an excellent introduction to the culture and mores of science and scientists. The nature of discovery, the critical role of competition and priority, the joy and drama of discovery, the role of women in science – these are some of the issues that emerge in a lively, witty play. We believe “Oxygen,” whether in play or book form, can serve an important educational mission, stimulating interest and debate about the nature of science in young people. To help teachers at both the secondary and university level to present the play to young people, we have written this study guide. It first summarizes the play, and gives an extended description of the main characters (a selection of literature on the protagonists is also included). Then it sets some of the historical background for the events of the play, especially that of an erroneous but plausible chemical theory, phlogiston. And the way the discovery of oxygen played the critical role in the chemical revolution. We also include an essay by one of us on the way science has been portrayed in contemporary theatre.